Innovation Academies

While other students around the state begin their day reciting the Pledge of Allegiance or listening to announcements in traditional classrooms with four walls, the 85 students at Halau Ku Mana charter school chant in Hawaiian under a tree-shaded tent in upper Makiki.

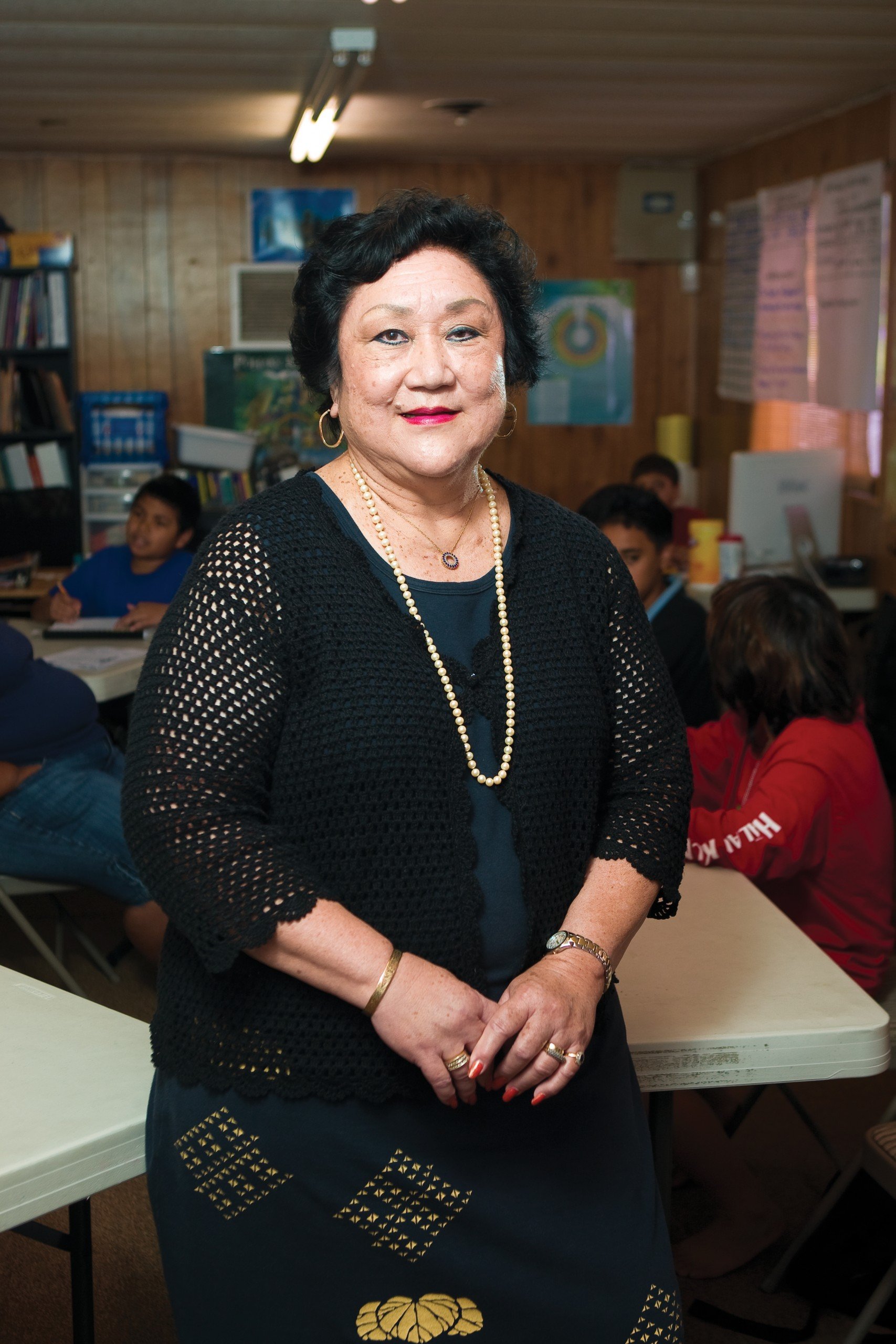

Deenie Musick, director

of Halau Ku Mana

Respectfully, they ask permission to begin a day of classes – math and reading, hula and Hawaiian language, history and maybe work in the loi or repairing the school’s small, double-hulled canoe. The traditional chant “sets a tone for their day,” says vice principal and kumu hula Kawika Mersberg. “It helps them focus.”

Meanwhile, down the mountain in gritty Kakaako, Voyager charter school welcomes 230 students into classes that include two grade levels in each room. The mixing lets children mentor younger pupils and bond with older ones.

In a school where the Golden Rule is part of the mission, parents join teachers in art projects, read to the class or help with math. “This school helps kids have a better opportunity to progress at their own speed,” says Layla Dedrick, a parent also active on the board. “They have pride in being Voyager students.”

Two hundred miles away in Pahoa on the Big Island of Hawaii – an area struggling with poverty – yet another charter is preparing students to care for 2,000 acres of virgin forest or to clear invasive mangrove from ancient fishponds.

At the Hawaii Academy of Arts and Science, endangered and indigenous plants are part of the lessons, along with an understanding of living sustainably. “Our kids are really proud of their campus,” says HAAS director Steve Hirakami of the 460 students from K-12. “There’s no vandalism. If you turn it over to kids, they’re going to take care. If you make it like an institution, they treat it like that.”

Regular public schools have their own buildings, but start-up charters pay for their facilities. Director Sue Deuber, inset, says Voyager’s rent is $360,000 a year.These are not your father’s public schools. Or maybe even your own. Launched more than a decade ago, Hawaii’s public charter schools have given families new options, established a safety net for students, and created a pool of flexible centers willing to test ideas. The three highlighted here, along with 28 others throughout the Islands, offer students and families choices based on the idea that children learn in different ways. Advocates say charters create many other benefits by innovating – including a stronger economy.

“If you give kids a great education – and charter schools can – it’s the best path to future economic growth,” says Nelson Smith, president and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, based in Washington, D.C. “Because of their flexibility and ability to innovate, charters can try out new things hard to accomplish in big systems. They’re kind of an R & D source for education.

“If some of our global economic problems can be traced back to low-performing schools in the U.S., that’s the place to start. There are other direct economic benefits as well – we’ve seen communities revitalized because of bringing in strong new charter schools.”

While charters survive with less money per pupil than regular Hawaii public schools, most have managed to keep children in class during Furlough Fridays by economizing elsewhere.

Voyager students Darius Chaffin and Aiya Bettinger show off artwork.

“I told everyone, ‘If we work hard and stick together and waste no time, we can squeak through,’ ” says Hirakami, of the Big Island’s HAAS. “Our program budgets are cut in half and each teacher gets money for curriculum. But I said, ‘Just because you have it, don’t spend it.’ And our teachers have been real frugal.”

This year, 11 percent of the state’s 177,800 public school students were enrolled in charters – a proportion that is increasing by about a full percentage point annually. Kamehameha Schools is so enthusiastic about the culturally based charters that it provides an additional $1,500 per student above state funding to those with 40 percent or more students of Native Hawaiian ancestry.

But the picture isn’t all rosy. Like regular public schools, the 31 charters face money and facilities challenges. Many schools worry about their survival, or are pondering further cuts, including turning away students, as funding continues to shrink. Also, because they are all different from each other – sometimes radically different – some are doing better than the average public school on measures such as math and reading tests, and some are doing worse. On average, math scores for charter students are far below those for students in regular schools, and last year, a lower proportion of charters hit their No Child Left Behind standards than regular schools.

“System change is not ‘Cup o’ Noodles,’ where you put in hot water and boom!” declares Rep. Roy Takumi, chairman of the state House Education Committee. “But we’re getting there and we’re going to get there. Charters have to be nurtured and encouraged. Once they get to be mature and you don’t see results, then revoke. But we’re far, far from there. The jury is still out.”

Many of the issues faced by charters are also faced by regular schools: facilities, funding, support from the state, accountability and, of course, scores. Here are areas to consider in weighing the advantages and disadvantages of charters:

Facilities

“It’s the facility cost that’s the huge disparity between regular neighborhood schools and charters,” says Sue Deuber, director of Voyager, which spends $360,000 a year on rent in a strip mall in an industrialized Kakaako neighborhood near downtown. “I could hire six more teachers with the amount I’m paying in rent. That’s our biggest single challenge as a movement. The conversion charters have buildings. But there are about six to 10 of us that are in private facilities where we pay top-dollar rent.”

Voyager holds classes in a made-over warehouse that shows few signs of its past.

Regular public schools that transform into charters are called conversion charter schools and they continue to have free use of their state Department of Education buildings and playgrounds. But startup charter schools must pay rent for their buildings – and they get no extra money for it.

Halau Ku Mana has had four sites in 10 years and now offers classes in nine portable buildings and several tents pitched on leased state land just below the Hawaii Nature Center in Makiki. “Facilities are a major issue for all charter schools,” agrees Deenie Musick, Halau Ku Mana director. “We had to put up tents because we didn’t have enough room. All of us are scrambling for grants.”

When charter schools were established a decade ago, the legislation did not include facilities money. It still doesn’t. But that was the price of getting the law approved by the Legislature.

“In the beginning, they (the charters) were very optimistic they could find benefactors,” says Takumi. “But, as the years went by, they realized you can only meet in a Quonset hut for so long. But what’s the tipping point? How do charters get a fair share of facilities money? On the other hand, how do you maintain the current levels for regular schools? Right now we have a $400 million backlog in repairs alone and eventually the charters would want maintenance money as well.”

A bill is moving this session to allow charters to be housed in underutilized regular DOE schools, especially in areas where the student population has dropped. “You could have a charter school within a school, but the DOE has to be open to it,” says Takumi.

Funding

The charter-school law includes a funding formula, but, in the last two years, funding has been cut, just as it has been for regular schools. But the charters started with less funding per pupil and the numbers went down from there.

“We’ve seen a 37 percent income loss in two and a half years,” says Hirakami, of HAAS on the Big Island. “This year, we’re getting about $6,200 per student. Last year it was about $7,400. The year before it was about $8,150. Last year it was do-able, but this year we’re just squeaking by. Next year, it’s going to be virtually impossible at $5,300 per student. You can’t give us that and expect us to survive. Somewhere in the $7,000 range could be sustainable.”

A study done several years ago by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute reviewing charters in 16 states found on average they were funded 22 percent below regular public schools. In the 40 states that now have charters – there are about 4,900 charter schools nationwide with about 1.6 million students – only a handful receive funding comparable to regular public schools. According to the 2009 Hawaii Superintendent’s Report, which has the latest figures, regular public school students were funded at an average of $9,876 a year in 2006. Since then, funding has increased: to $11,060 in 2007, about $11,800 in 2008 and an estimated $12,399 in 2009, according to the DOE. This is much more than Hawaii charters receive; however, DOE spokespeople say these dollar amounts include additional monies and are not comparable to the per pupil money given to charter schools.

It’s virtually impossible to tease out a comparable figure because the funding formulas for charters and regular public schools are different. Regular school funding per pupil includes state general funds, special and trust funds, Title 1 and other federal funds, and monies covering fringe benefits and risk management. By comparison, charters generally receive a lump sum from the Legislature that’s divided among them. They also receive federal funds, grants for which they apply, and this year, stimulus funds.

The Weighted Student Formula allots additional money to special-needs students at regular schools. The charter schools receive services for special needs students from the DOE or on contract from an outside agency, on top of the standard charters funding formula.

Test scores

So far, Hawaii’s data does not prove that charter school students do better or worse on tests than regular public school students. In Hawaii during 2008-9, 29 percent of charters achieved Adequate Yearly Progress – AYP, a measure based on test scores – while 36 percent of all public schools did. However, in 2007, 67 percent of charters met testing standards, while 65 percent of all public schools did. In looking at student achievement, students in charters surpass the state averages for reading as they reach higher grades, but fall below them in math.

“The Rand Corporation just did a study in Chicago and Florida and found a significantly higher chance of kids in charter schools finishing high school and going on to college,” says Smith, the national charter advocate. “Charters are particularly effective for kids left behind their peers in achievement. They move them ahead faster.”

Flexible, responsive, accessible

“What separates charters is you’re not bogged down in minutiae and bureaucracy,” says national charter school consultant Margaret Byrnes, who coaches seven Hawaii charter schools on leadership but is based in Florida. “You don’t have to go through 1,000 channels to get things done.”

For example, when Hirakami of HAAS wants to add a program to the curriculum, it can happen in a few months. He presents a proposal to his local board by May, a decision is made in June, the program is developed in the summer and the children are involved by fall.

“We’re adept at making quick changes,” says Hirakami. “There are no layers. In developing a stewardship program to care for 2,000 acres of virgin forest and cleaning up and helping restore fishponds, within months I did a cost analysis, gave it to our board, and put it into effect. That program is now finishing its second year and is very successful. We attract a lot of Native Hawaiian students and that program provides a lot of learning about native forests and invasive species.”

Parent Steve Nottingham says his ninth-grade twin sons are thriving at HAAS – a far different story than in their previous school. “They do ‘bottom up’ curriculum, giving students input in how it should be run,” he says. “They say, ‘This is your school, how do you want it run? Are teachers meeting your needs? Are they receptive to your questions?’ That’s a complete difference: The children decide what’s happening for them. There’s a lot of group decision-making rather than top down.”

The school has also responded to parents’ desire for more emphasis on core subjects. The result: Morning instruction includes two-hour blocks of social studies, science, math and language arts, while afternoons are left open for electives – things like aikido, yoga, art, music, swimming, health.

“We have a board here – a stakeholder group including a teacher, staff person, administrator, student, parent and community member – that can make quick and efficient decisions at the local level,” says Hirakami. “We involve the community, too, and usually pick someone with business expertise or who works for the County. Being right here in the community, being able to make efficient decisions and being accessible, that’s something lacking with the other public schools.”

Small schools with involved parents

Many studies show that most children do better in small schools where everyone knows their name. They also do better when their parents are involved in their education. “Where parents are helping and volunteering typically their children do better,” says consultant Byrnes. “Whenever parents are involved in their child’s education it brings everybody to the same focus.”

Rep. Takumi agrees. “The research is persuasive that smaller schools are better than big. Just by that mere factor alone you have the ingredients for success.”

You don’t have to tell that to Dedrick, a former public school teacher who has a third grader and a fourth grader at Voyager. “Because charters tend to be smaller theoretically, they have a lot going for them. You have to have parents and community people dedicated to making it work. If you think about it, the ingredients for an optimal learning environment are there: small class size, parent involvement and community involvement. Those ingredients will make any school better.”

The future

Currently, the number of conversion charters is capped at 25 – there are now five – while the overall number of charters is 31. Twenty-six charters are startup charters. The law allows a new charter to open each time one of the existing charters receives accreditation; the lengthy process of accreditation is ongoing. However, the Charter Review Panel, which oversees the law, has suspended applications for new charters until rules for charter revocation are approved by the Board of Education. That process is almost complete.

Takumi envisions eliminating caps and allowing charters to blossom naturally. “The whole point of charters was they were meant to be experiments, to have flexibility and autonomy and freedom from red tape. The feeling was that was hampering achievement of the school.”

But he says some rules are needed to rein in failing charters. “We need to promulgate rules not just to revoke but to issue and review. One of my goals was to put some accountability into it. We want the good schools to succeed and to stop those schools that aren’t succeeding, to give someone else a chance. On average nationally, about 10 percent of charters are revoked annually. Then new charters spring up. It makes sense. These are experiments and some succeed and some don’t.

“The Board of Education is close to finalizing rules for revoking charters and in the next few months everyone will know what the rights are and what they’ll be held accountable to. If this is finally getting done, then by all means we should lift the cap. The Legislature would be very interested in lifting the cap. And we should have multiple authorizers.

“No matter how you slice it,” says Takumi, “they’re all our kids and we have a moral obligation to provide them with options and opportunities to learn.”

How much money do charters get per pupil?

Year

2010 $5,300*

2009 $6,200

2008 $7,400

2007 $8,150

2006 $8,000

*expected level

Source: charter schools

Charters want to partner with businesses

By Beverly Creamer

“All of our expenses are going up and our funding is going down,” says Sue Deuber, director of Voyager charter school in Kakaako. “Some of the smaller charter schools are in danger of closing this year. What saved us was the extra federal money we got through the stimulus act.”

Voyager has geared up fundraising to bridge the money gap – a concert is planned for May 14 at Aloha Tower – but is also one of many local charters looking for business partners.

“Education-business partnerships are popular on the Mainland,” says Deuber.

A business can help a school by:

• Encouraging employees to read to students or work on school-beautification projects;

• Allowing employees to volunteer as speakers, mentors or tutors;

• Setting up a job-shadow program;

• Paying for or donating new technology.

“There are all kinds of partnerships that involve businesses, ranging from providing pro bono help for back-office functions to directly making grants for playground facilities or equipment,” says Nelson Smith, head of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. “Very often you see community leaders and business people on charter school boards where their expertise is really needed.”

“It’s a win-win,” agrees Deuber. “The school benefits and businesses do so much better when their employees are involved in some effort to give back to the community. They’ve actually seen their bottom lines go way up. The employees feel valued; they feel like they’re making a difference.”

How to help

• Mentors: The Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii encourages business leaders to mentor high school seniors at any school on projects that lead to a special recognition diploma. Go to helphawaiischools.com

• Voyager: To volunteer at Voyager charter school, call 521-9770 or go towww.voyagerschool.com

• Other schools: To volunteer at other schools, call their front office. For a list of charter schools, go to http://www.hcsao.org/hicharters/profiles

More Coverage:

Grading Our Schools

+ Top State for Schools

Hawaii Business magazine’s sister publication, HONOLULU, covers Hawaii’s public education system annually. Its May issue has two major stories on the subject.

First, “Grading the Public Schools,” is HONOLULU’s exclusive ranking of 257 public schools statewide. Using official Department of Education data, the magazine scores each school on five measures: student performance on reading and math tests, plus satisfaction scores given by the teachers, parents and students.

We often hear that our public schools consistently rank as some of the lowest performing in the nation. But which state has the nation’s best public schools? Education Week magazine and other national rankings say it is Maryland. In HONOLULU’S second education feature this month, “The Maryland Lesson,” senior writer Michael Keany finds out how that state turned its schools around and identifies solutions we have yet to try here.