I Donated a Kidney to a Stranger. You Might Consider It Too.

The National Kidney Foundation says about 90,000 people in the U.S. need a kidney, and 12 people die every day while waiting for one.

At about 3:30 p.m. on April 23, 2024, I was rolled into an operating room at The Queen’s Medical Center to have major abdominal surgery. There was nothing wrong that required medical attention – I celebrated my 25th birthday earlier that month and had a clean bill of health. No, I was in the hospital by choice, and though my family was anxious, I was eager for this procedure called a nephrectomy.

When I awoke from the four-hour operation, I was super groggy and in moderate pain but, without a doubt, happy: After a year of paperwork, medical tests and psychological evaluations, I was finally able to donate my spare kidney to someone who desperately needed it.

My “Why”

It may sound strange, but I never had any doubts about my decision to donate a kidney to a stranger. During a philosophy class about altruism in my senior year of high school, I learned about living organ donations and was immediately captivated by the idea.

I already knew you could donate your viable organs after you die, and that a single word added to your driver’s license – “donor” – would make that happen. But I learned in that class that kidneys are among the few organs you can donate while alive. That’s because we have two but only need one, and the kidney you keep will gradually grow in size and strength.

In a less common procedure, you can donate a little more than half of your liver because it will re-grow inside both yours and the recipient’s bodies. Even more rare, portions of lung, pancreas and intestines can also be donated while you are alive.

But kidneys are by far the most needed organ. Of about 100,000 Americans on organ transplant lists, some 90,000 need a kidney. More kidney transplants happen every year: A record-breaking 28,000 were performed nationwide in 2023, but it was far from enough. According to the National Kidney Foundation, 12 people die every day waiting for a kidney transplant.

What Kidneys Do

The kidneys are bean-shaped organs, each about the size of your fist, located just below the rib cage, one on either side of the spine.

“The kidneys are designed to get rid of the things that shouldn’t be in your blood, and then they fine-tune all the things that are there, so you make urine to get rid of extra water,” says Dr. Christie Izutsu, my nephrologist at the Queen’s Transplant Center. “And in the urine, all the extra toxins or the chemicals that shouldn’t be there are removed.”

Each of your kidneys has about a million filtering units called nephrons, which is the origin of nephrology, the word for the study of kidneys. “The kidneys are great sensors, and they can tell what needs to stay and what should go,” Izutsu says.

“The problem with kidney disease is often silent. There are no symptoms until the kidney disease is relatively advanced.” Early signs may include leg swelling, blood pressure that’s hard to control or blood in the urine, but those symptoms aren’t always present early on or are too inconspicuous to raise an alarm, she says.

“It’s not very specific. Over time, people just feel tired, no energy, poor appetite, a little bit of foggy thinking. … A lot of folks who are younger, who develop kidney disease gradually, really don’t notice any symptoms until they either get a transplant or they’re on dialysis. And then they say, ‘I didn’t actually realize how junk I felt till I felt better.’ ”

Because of that, chronic kidney disease usually goes undetected until an advanced stage. According to Harvard Health Publishing, symptoms don’t normally present themselves until “more than 80% of kidney function is lost.” But for patients with end-stage kidney disease, the condition is no longer subtle. Without dialysis, they’re unable to filter harmful toxins from their bodies; many say they feel like they’ve been poisoned.

Izutsu says per capita, Hawai‘i has one of the highest rates of chronic kidney disease in the country, and more young people are affected here than in other places.

“I’m not certain you can pinpoint one factor, but I think some of it is tied in ethnically, culturally.” For example, “we do have a strong Asian community,” she says, and Asians have a heightened “ethnic specific” risk for developing glomerular diseases that hurt kidney function.

Also, Hawai‘i has many people who have lived in “places around the world that do not have nephrology, and so a lot of patients come here with really advanced disease, and unfortunately, by the time they get here, they have stage five kidney disease and need to start dialysis,” Izutsu says.

Generally speaking, “We have a lot of folks who just don’t have access to good health education and disease management.” Today, Izutsu says, more focus is placed on addressing some of those disparities.

One option for people nearing kidney failure is dialysis, where patients are hooked by two needles to a machine that tries to mimic what kidneys should do, Izutsu says. One needle sends your blood into the machine to be filtered, the other carries the filtered blood back into your body. The unpleasant experience typically takes three to five hours per session at a dialysis center, with patients repeating the procedure two to seven times a week.

And unlike a working kidney, dialysis doesn’t help produce urine. Many dialysis patients make little to no urine, which means excess fluid accumulates in their bodies, causing swelling, shortness of breath and/or weight gain. Dialysis helps to remove some extra fluid but not as effectively as working kidneys do through regular urination.

Patients often feel exhausted for hours after dialysis. And because dialysis is so time-consuming, it can make it nearly impossible for some patients to hold a job, which leads to financial strain that makes matters worse. The bottom line is that dialysis is not a long-term solution: “Unfortunately, dialysis is not perfect, and a lot of patients pass while waiting for a kidney [transplant],” Izutsu says. According to the National Kidney Foundation, the average life expectancy on dialysis is 5 to 10 years.

Giving the Gift of Life

Receiving a transplant is far superior to dialysis because a transplanted kidney can effectively filter blood and produce urine 24/7 for more than a decade, doctors say. Kidneys can come from deceased or living donors – both types of transplants usually work well, they say – but kidneys from living donors are better.

Izutsu says a kidney taken from a deceased person has little or no blood flowing through it until after it’s transplanted, which can reduce how well it works or how long it will last once the recipient gets it. “We do know that deceased donor-derived kidneys tend to last for about 10 to 15 years, sometimes far longer, though. But a living kidney has a longer life expectancy,” she says.

In addition to better blood flow, “the benefit of having a living kidney is that we’ve had the ability to do extensive testing [beforehand] on the donor, and we know that you are healthy, otherwise you wouldn’t take the kidney.” For deceased donors, much less testing is possible, so how well their kidneys will perform is more of a gamble.

The vast majority of transplanted kidneys come from deceased donors – in Hawai‘i, it’s 80% to 90% of them, Izutsu says. Out of the 620 kidney transplants since 2012 at the Queen’s Transplant Center, only 75 came from living donors.

How Good Samaritan Donors Form Chains

There are two kinds of living organ donations: directed and nondirected. Ninety-five percent of living kidney donations are directed, meaning the donor has an intended recipient. But a person can’t donate to a loved one or other specific person if their blood types, tissue types and/or antibodies aren’t compatible. The recipient’s immune system would immediately reject the kidney.

The National Kidney Registry makes nondirected transplants possible. The database includes information on people who need kidneys and those willing to donate them. It helps coordinate exchanges between multiple pairs of people: A donor gives a kidney to a stranger who is a match and in return, the donor’s loved one who also needs a kidney, receives one from another compatible stranger. These paired exchanges form what are known as “donor chains.”

The biggest challenge, however, is that donor chains typically need to start with a nondirect donor. Also known as an altruistic or “Good Samaritan” donor, these are people willing to donate to anyone who’s a match, with no intended recipient in mind. But altruistic donors are rare. According to a 2022 study published by the National Library of Medicine, only 5.6% of living kidney donors are nondirected.

Starting a chain was a huge motivating factor for me, as a nondirected donor. Six months after surgery, I learned that eight people were involved in my chain – four donors gave a kidney and four recipients received a kidney. My chain moved west to east and involved at least three different hospitals: Queen’s in Honolulu, the UCSF Transplant Center in San Francisco and the NYU Langone Transplant Center in New York City. It was a huge team effort involving dozens of people across the country.

One big perk for nondirected donors: The person gets five vouchers from the National Kidney Registry. The donor chooses five individuals who are not in imminent need of a kidney transplant to receive a voucher, which can be activated if any of them ever need a kidney transplant in the future, says Natalie Lamug-Funtanilla, a nurse and the living-donor coordinator at the Queen’s Transplant Center. The vouchers give people priority for transplants through the kidney registry, she says. Once one voucher is redeemed, the other four are voided.

The registry offers other benefits to help cover expenses and wages lost for both directed and nondirected donors. This includes travel, lodging and dependent care costs – I was reimbursed for all of the Uber trips I took to Queen’s for testing and visits – plus up to $2,000 per week for up to 12 weeks, for a maximum of $24,000 in lost wage reimbursement. Most donors take about two weeks to two months off work to recover. (It’s illegal for employers to fire employees for taking that recovery time.)

John and Jill’s Story

After my left kidney was removed in surgery, it was rushed onto a flight to San Francisco (Godspeed!), where it was transplanted into my recipient the next morning. At that point, all I knew was that the recipient was in California and that our tissues were compatible. The recipient’s identity was kept secret from me and vice versa, and there was no guarantee I would ever find out who they were.

But three weeks later, Nurse Lamug-Funtanilla handed me a letter from my recipient, a 65-year-old man from San Francisco named John Jweinat. In part, it read: “For the last year, I have undergone dialysis four times a week, and it was very challenging for me. My daughter tested to be a kidney donor for me. Although we had compatible blood types, we did not have compatible tissue types, so she could not donate to me. As a result, we entered the Paired Kidney Exchange Program.”

“On Wednesday, April 24, 2024, your kidney was transplanted into me at UCSF Medical Center in San Francisco, and the surgery was successful. In return, my daughter donated her kidney to a 41-year-old woman in New York City. … Your decision to donate your kidney not only saved my life, but also the life of a 41-year-old woman in New York City, who wouldn’t have received my daughter’s kidney unless you donated your kidney to me.”

His letter moved me to tears and I was so relieved to hear that he and his daughter were doing well. Honestly, I was initially surprised by his age – he was 40 years older than me – since I was told that the process tries to pair donors with recipients of similar age. But I was glad, too; my parents are only one year younger than my recipient, and I would be absolutely devastated if I lost them now.

In his letter, John shared that he and his wife of 49 years, Maggie, have five children and four grandchildren. I’m thrilled that my kidney has given him more time with his family – in good health – and that he and his wife will be able to properly celebrate their 50th anniversary in August.

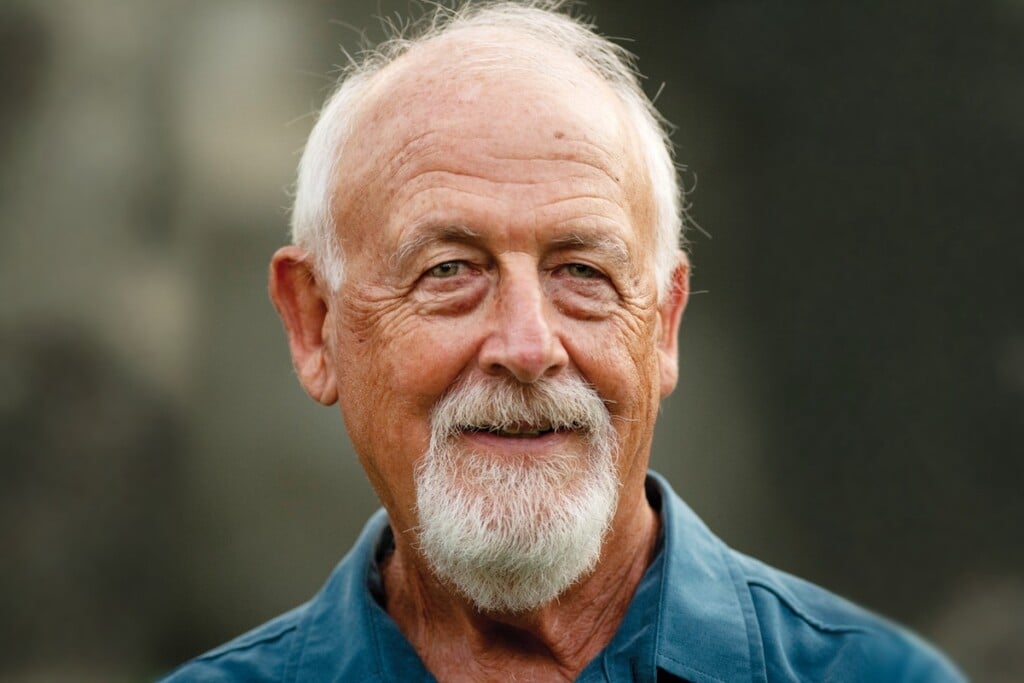

Six months after our surgeries, John happily agreed to share his perspective as a recipient for this story. “I originally started having issues with my kidneys when in my early 30s,” John says. His issue was “leakage of protein, which causes scarring to the kidney.” Six years after receiving that diagnosis, his kidneys were failing to the point that he needed dialysis.

His wife, Maggie, donated her kidney to him and that transplant lasted 10 years before failing. Then he received a second kidney from a deceased donor. “It was a fantastic match, and everything went well” for 17 years – longer than most deceased-donor kidneys – before he had to return to dialysis four days a week.

Once that happened, his and his wife’s schedules changed completely. On dialysis days, he had to wake around “four o’clock, get in the shower, have my coffee, and leave at like 5:30 to get there at 6, and from 6 to 10, I’d be doing dialysis.”

But John is a glass half-full kind of person: “On dialysis, some days are good. The majority, you feel weak, dizzy, exhausted, sometimes you might even faint. … But the next day after dialysis, you’re pretty strong again, and you feel normal, actually, for that one day.”

Coincidentally, he received his third transplant with my kidney exactly one year after he resumed dialysis. And my birthday is April 2 – 4/2 – so when I found out his surgery was scheduled for April 24, 2024 – 4/24/24 – I took it as an auspicious sign. April also happens to be National Donate Life Month.

“Within two, three days, I was feeling great, really. Urinating, I had no pain, took no pain pills, nothing. And you know, they said that’s pretty rare, but everything went perfect,” he says of his immediate recovery. Six months after surgery, he says: “Everything so far is so good. Blood tests are good. Everybody’s happy and couldn’t be more thankful.”

He’s also extremely grateful for his daughter, Jill, who donated to the woman in New York City so he could receive my kidney: “God bless her, my daughter was very kind and generous to do that for me.”

Jill told me that as a child she remembers her father on dialysis and being “constantly worried” about losing him. Donating “was always something I wanted to do, and I think it’s because I saw my mom do it,” she says. When his second transplant started failing and it became clear he needed a third, she stepped up.

“It wasn’t a difficult decision for me. I don’t think a lot of people understand it or think it’s normal, but for me, it was a no-brainer,” Jill says. Although she and her father were crushed when they found out they weren’t a match, the news ended up being a blessing in disguise; by entering the paired kidney exchange program, they helped form a donor chain.

“It was great that I was able to help my dad get a kidney by doing it, but also that I got to actually help save someone else’s life. And so in the process of putting myself in the exchange, I was able to help save two people’s lives instead of one.”

As for John, he has some words of wisdom: “If you have your health, you’re the richest person in the world. Having your health, there’s nothing better than that.”

“The Best Physical You’ll Ever Have”

When I contacted the Queen’s Transplant Center about becoming a living kidney donor, I heard first from Lamug-Funtanilla, the nurse who was by my side throughout the lengthy process – from first contact through pre-op through my recovery.

Her role as living-donor coordinator is to educate, support and manage the care of potential donors throughout the process, she says. “We provide them with information about the donation process to help patients make informed decisions. We coordinate the visits, meetings with the members of our transplant team, and we also schedule and arrange for the evaluation pre-op testing, such as blood and urine tests, imaging and cardiac testing.”

My transplant team included Nurse Natalie, Dr. Izutsu, an anesthesiologist, two Queen’s transplant surgeons – Dr. Lung Yi Lee and Dr. Makato Ogihara – as well as a social worker, pharmacist, nutritionist, financial coordinator and psychologist. And then there were the attentive nurses who gave me VIP treatment during my two days at the hospital, making sure I was in as little pain and discomfort as possible.

Early on, Lamug-Funtanilla also connected me to a living-donor advocate. These advocates are altruistic donors who share their personal experiences with potential donors and answer questions about what the process is like. My living-donor advocate never learned who her recipient was, but she made it clear that it didn’t bother her or take away from her experience. Not knowing is an outcome she said I needed to prepare for and accept if I were to donate, and we agreed that all recipients are grateful for their donors, even if they choose not to come forward. An altruistic donation is about performing a good deed and expecting nothing in return – not even a thank you. Talking with her was especially insightful and reassuring.

Donor candidates must be in excellent health to be approved, so the testing is beyond thorough: extensive blood work and urine samples, renal scans, chest X-rays, EKGs, echocardiograms, and abdomen and pelvis CT scans. According to Jill, my recipient’s daughter who also donated, the team at UCSF described the process as “the best physical you’ve ever had.”

My experience going through evaluation was educational and my transplant team always had my best interests at heart. They never once pressured me to follow through but were incredibly supportive with my informed decision to donate and assured me I had the right to change my mind at any time.

Donors have an exit strategy in place that allows them to stop the process in a way that “their decision to opt out will remain confidential,” Lamug-Funtanilla says. “Potential kidney donors can change their mind about donating at any point throughout their process. … They have all the way up until the day of the surgery that they can change their mind, and we need to ensure that their decision is completely voluntary.” Even the minute before I was put under anesthesia on the operating table, I was asked one last time if I was sure I wanted to go through with it.

Surgery and Risks

The world’s first living-donor transplant took place at a Boston hospital in 1954. Ronald Herrick – who donated a kidney to his identical twin brother, Richard – went on to live another 56 years. Richard lived an active, normal life for eight years after the transplant; his death was unrelated to that procedure. Hawai‘i’s first living-donor transplant was in 1969.

“Donor nephrectomy used to be an open large-incision surgery, requiring more postoperative pain management and longer hospital stay. We (in Hawai‘i) switched from open nephrectomy to laparoscopic nephrectomy in 2007,” Ogihara, one of Queen’s transplant surgeons, wrote me in an email.

In layman’s terms, medical advances have fine-tuned the living kidney donation process to the point where it’s now a minimally invasive, relatively safe procedure. “Nobody died directly from donating in Hawai‘i, but some unfortunately in the mainland over the years. Risk of dying from donor nephrectomy is still calculated as 0.02%, which is much safer than nephrectomy for cancer (about 1%),” Ogihara wrote. The need for a second operation, major organ failure or bleeding to the point the patient needs a transfusion, “are very low, less than 1%.”

In regard to long-term risks, Penn Medicine reports that about 25%-30% of kidney function will be permanently lost and individuals who donate a kidney have about a 1% chance of developing kidney failure. In the rare event a donor goes on to need a transplant, all living organ donors are automatically put to the top of the waitlist for a kidney transplant from a deceased donor. And donors that go through NKR’s Donor Shield program are given priority for a living donor transplant, should they ever need it.

Research actually indicates that living organ donors tend to live longer, on average, than the general population. This phenomenon is believed to stem from three key factors:

- Donors must undergo extensive testing and meet stringent health standards to qualify for donation, ensuring they are in excellent physical condition.

- Many donors remain highly motivated to maintain healthy lifestyles and prioritize their well-being after donation.

- Emotional well-being plays a crucial role in overall health. Donation can be a deeply rewarding emotional and spiritual experience, and many donors report enhanced self-esteem, optimism, and a profound sense of fulfillment from helping another person in a time of need.

I stayed in the hospital for two nights after surgery, and the nurses made sure I received appropriate doses of medications to help minimize pain.

Two weeks in, my recovery started to significantly improve. And after one month, I was mostly back to normal, although I was only allowed walking and other light exercise until six weeks. Three months into post-op, I noticed no difference at all between how I felt before donating my kidney and after. My scars healed nicely in that time and are now barely noticeable.

Jill’s recovery also went smoothly. “You do need a support structure that’s going to help take care of you, but I will say I was walking around the second or third day. … It’s not easy, but it’s not like you’re out of commission for several months. I see scars on my body, but outside of that, I don’t feel a single difference in terms of how I feel prior to surgery versus after surgery. … I do feel a massive difference in terms of knowing that I helped, quite literally, save someone’s life.”

Final Thoughts

To me, the coolest thing anybody can be in life is kind. It’s cooler than being smart, funny, charismatic, hardworking, creative or athletic. Those are wonderful qualities to have, of course, but I believe compassion makes the world go round. So, I strive to live my life guided by kindness as my core value. And donating was a fantastic way to put that principle into action.

If it’s something you could see yourself doing, wonderful! I highly recommend that you consider it, and even start the process, which you can stop at any time.

That said, nobody should ever feel pressured to donate. Nor are you a bad person if the thought of surgery or the risks worry you too much. What I will implore of you is that you make a concerted effort to perform small (or even medium-sized) acts of kindness every day, whether that’s donating money to charity, volunteering, advocating for good causes, helping a neighbor or even complimenting a stranger. Not only do these acts brighten someone else’s day, they will make you a happier, more fulfilled person. It doesn’t have to be a grand gesture; not all of us have the time, money or resources for that. But small acts of kindness add up and make the world go round too.