How To Replicate Kahauiki Village

Dealing with homelessness is not just the responsibility of the government or nonprofits. As Kahauiki demonstrates, everyone has to pitch in.

What was once a barren stretch of dirt, gravel and nondescript trees and shrubs is now a dynamic community of 30 formerly homeless families – and soon many more will join them.

Several people in government and in the nonprofit sector agree: Kahauiki Village is a success. It’s providing working families with permanent, affordable homes and the services they need to help them rebuild their lives.

The project off Nimitz Highway was built under an emergency proclamation that allowed leaders to fast-track its development and lower costs, but they say it couldn’t have been done without the help of the community as people from private businesses, nonprofits and the government donated their time, services and products.

Today, other groups are looking to incorporate some of the lessons learned at Kahauiki into their own developments. What’s important, many agree, is that the community continues to get involved in housing the homeless.

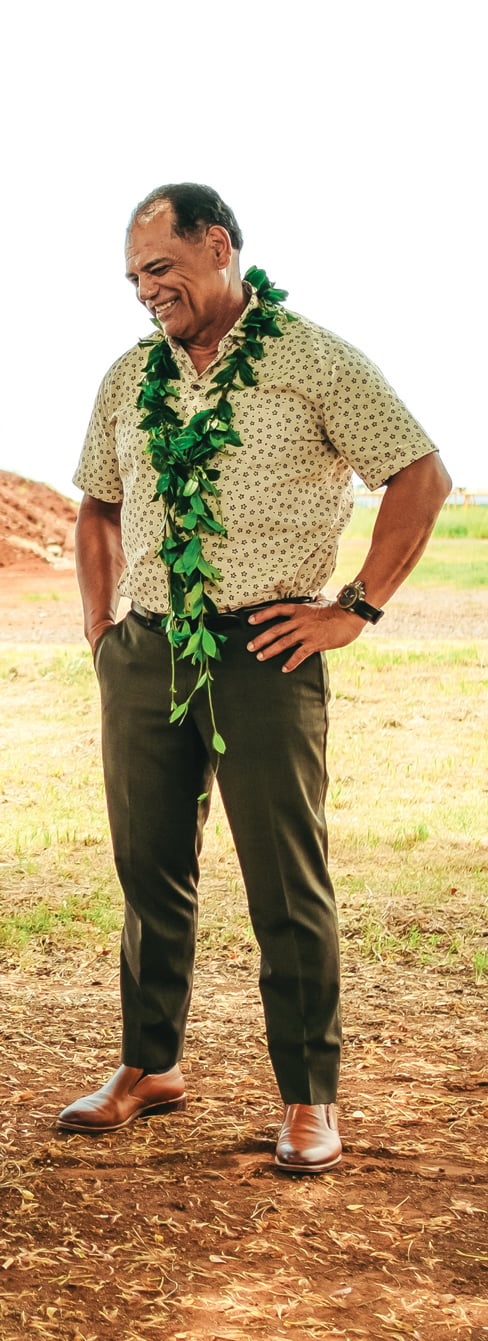

“All of us who worked on the project believe that Hawaii will be able to address the homeless issue if we all step up and do something about it,” says Duane Kurisu, organizer of Kahauiki Village. “It can be done.” (Kurisu is also the chairman and CEO of aio, which owns Hawaii Business magazine.)

Duane Kurisu, Chairman and CEO of aio, is the catalyst for the creation of Kahauiki Village. | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

ADDRESSING HOMELESSNESS

Located on a peninsula just Diamond Head of Keehi Lagoon Beach Park, Kahauiki Village provides permanent, affordable housing to 30 working families who have already gone through transitional housing programs.

Residents receive on-site case management provided by the Institute for Human Services. The idea, according to Kimo Carvalho, director of community relations at IHS, is to provide the residents with everything they need to successfully break the cycle of homelessness.

One barrier that would keep families homeless or cause them to become homeless is child care, he says. Providing on-site child care at a low rate allows parents and guardians to work. In addition, the village’s low rents – $725 per month for a one-bedroom unit and $900 a month for a two-bedroom, both of which include electricity, gas, water, internet and cable TV – incentivize families to save and build money management skills.

Corbett Kalama, executive VP of the Harry & Jeanette Weinberg Foundation’s Hawaii office, says Kahauiki succeeded because the state and county governments fulfilled their responsibilities in helping move such projects forward. | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

The village features a day care, preschool and laundry, plus access to transportation and partnerships with nearby employers to provide jobs to residents who need them.

“Our goal is to see these families mobilize,” Carvalho says. “And they will never be homeless again because they have ended their cycle of homelessness. It’s coupling the city’s affordable housing strategy with the national strategy to end the cycle of poverty.”

What makes Kahauiki Village unique, several sources agree, is its emphasis on community – the broader community that built the village and the nascent community that is now living in the village.

The village was constructed via a public-private partnership. The City and County of Honolulu provided $4 million worth of off-site water and sewer infrastructure. The land is owned by the state but leased to the aio Foundation for $1 a year. And many private organizations and community groups donated their time and resources to bring the village to life.

“We were very, very lucky. Everybody in Hawaii was so giving; that’s how we were able to pull this off,” says Lloyd Sueda, project architect. “They would call us and say, ‘We would like to participate,’ and that’s how we put this thing together.”

Kurisu says the community culture at the village was evident a few days after families moved in. A parent would escort resident children to nearby Pu‘uhale Elementary School and back. Residents have taken responsibility for their self-governance and formed a resident council and held a garage sale to fund community activities and gatherings. In the future, community gardens will be set up, with a plot for every household, something Kurisu says is an important community builder.

The community culture stems from residents’ desire to grow together at this new stage in their lives, Carvalho says. All the residents are in similar situations – they all want to work, get their children into child care, learn about budgeting and financial literacy and escape the cycle of poverty.

Kurisu adds that several community groups have adopted the village, such as Rotary District 5000, whose members will engage resident families to help maintain the landscaping, and aio Hawaii Director of Strategic Planning and HR Ken Miyasato, who opened a karate dojo at the village.

Ken Miyasato, director of strategic planning & human resources at aio, founded a karate dojo at the village. | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

The second phase of construction will begin in January. Construction will include the remaining 114 homes, plus a larger recreation center, additional child care and preschool space, several playground areas and a hale.

Marc Alexander, executive director of the Honolulu Office of Housing, says Kahauiki Village is an effective solution to solving homelessness – one that can be replicated: “It outlines what happens when public and private work together. It outlines what happens when leadership is able to bring the strength that everyone has to offer.”

HOUSING THE HOMELESS

The establishment of Kahauiki Village comes as the state is finally seeing a decrease in its homeless population. According to the 2018 Point in Time Count, there are 6,530 homeless people across the Islands. That number was 7,220 in 2017. Before 2017, says Scott Morishige, the governor’s coordinator on homelessness, the homeless population would increase every year.

He says increased resources and funding for programs like Housing First have contributed to this decrease. Housing First programs are geared toward chronically homeless individuals dealing with mental illnesses or substance abuse or both and provides them with supportive case management and vouchers and sometimes places them into specific housing units.

“There’s no cookie-cutter solution,” he says. “But I think despite what the challenges are … it is positive that we’re making headway.”

Housing is the key to getting homeless individuals off the street, Morishige says. In addition to being a program, Housing First is also a philosophy that focuses on getting homeless individuals into housing as soon as possible, without requiring preconditions, like sobriety. Once they are in housing, social service agencies can help them deal with such problems.

One of the challenges of housing the homeless, Morishige says, is the state’s need for more housing. The state has a goal to build 22,505 affordable rental units by the end of 2026, 9,002 of which would be on Oahu.

In 2015, Gov. David Ige signed an emergency proclamation that allowed several permanent affordable housing projects, including Kahauiki Village, to be developed at an accelerated pace if they were targeted at the homeless population. The proclamation was in effect until 2016, but projects like Kahauiki Village that began construction under the proclamation can continue to be developed.

“We knew the need really was for housing. We needed more long-term places where people could go that were specifically dedicated to people coming out of homelessness,” Morishige says. Under the proclamation, the state partnered with the counties to identify projects already in the pipeline.

Projects include Kauhale Kamaile in Waianae, which consists of 16 prefabricated modular units; the Halona Modular Housing Project in Waianae, which consists of three modular units; the 1506 Piikoi Street Project, which consists of 42 apartment units; Beretania Hale, which consists of 24 apartment units; and Winston Hale, which consists of six micro-units in Chinatown. Another permanent housing project was built in Kona on Hawaii Island, called Hale Kikaha, which consists of 23 micro-units made from shipping containers.

Some of these projects also house people at risk of becoming homeless, but Morishige says the focus was on creating housing opportunities for already homeless people, a population that struggles in the private rental market, where they sometimes encounter biases – something the state has worked with landlords and property managers to overcome.

He adds that the projects built under the emergency proclamation filled up shortly after opening. “I think it really shows how much demand there is to have these types of dedicated housing programs in the community,” he says. “So what we’re trying to do just as a system is figure out how do we provide the right types of support, whether it’s bringing additional types of units online or also shoring up subsidies that people need.”

Corbett Kalama, executive VP of the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation’s Hawaii office, says Kahauiki Village was successful because the state and county governments acknowledged and fulfilled their responsibility to help move such projects forward. Typically, projects like these are hindered by the challenges of getting permits and zoning variances and the costs of development. The foundation recently donated $3 million to support Kahauiki Village’s next phase of construction.

Carvalho says the emergency proclamation brought developers and homeless service providers together to help solve one of the state’s main challenges.

“We know our homeless clientele better than anybody, and for developers and for government to partner with IHS and to be able to actually talk amongst each other to understand what clientele needs are, as you’re designing facilities and infrastructure, that’s a big deal,” he says.

TEMPORARY PLACES

Earlier this year, the state Legislature appropriated $30 million for the establishment of a three-year ohana zone pilot program that would provide temporary places for the homeless to stay. The state could open up to six ohana zones: three on Oahu and one each on Maui, Kauai and Hawaii Island.

“The big question now that we have passed this is how is it going to be implemented because truly we can’t continue what we’re doing, which is basically pushing people from neighborhood to neighborhood,” says former state Sen. Will Espero, one of the main authors of the ohana zone bill.

“We needed more long-term places where people could go that were specifically dedicated to people coming out of homelessness.”

– Scott Morishige, Governor’s Coordinator on Homelessness

At press time, the state was still determining what exactly ohana zones would look like and how they would be maintained. Espero says an ohana zone is essentially a bare bones housing development built at the lowest cost to house homeless people temporarily. ‘Ohana zones would also provide services to help residents transition to permanent housing, and they would ideally be located near bus lines or have access to other transportation. He also envisions that ohana zones would be created for specific subpopulations, such as one for homeless families, one for single homeless adults and another for the mentally ill or those dealing with substance abuse.

None of the $30 million had been spent as of early October, according to Morishige. The state wants to use the money to potentially partner with the counties and state agencies to identify facilities that can be used to pilot “site-based” supportive housing or to bring on line more emergency housing or bridge units, he says. In a site-based supportive housing project, all units would house chronically homeless individuals who need intensive support services long-term because of mental illness or substance abuse.

The ohana zones must be built on state or county land. Morishige anticipates it will be hard to find available land with infrastructure already in place. Another challenge, he says, is nimbyism – people generally don’t want these facilities in their neighborhoods. He says despite education efforts, there are still many assumptions about what homeless people are like.

“I think, definitely, as you bring these projects on line, community engagement is a big part of that – to really talk to the community and let them know what’s going to be offered and what types of supports are being provided,” he says, adding that it’s possible the ohana zones could be created via public-private partnerships like Kahauiki Village.

Kurisu says that private partners need to be committed and passionate and understand the importance of rebuilding people’s lives: “I don’t think government can or should do ohana zones by itself,” he says.

BUILDING COMMUNITIES

Now that the first phase of Kahauiki Village is complete, says project architect Sueda, he and other leaders are getting inquiries from other communities about how they can create something similar.

In Waianae, the Pu’uhonua o Waianae encampment is looking for a new parcel of land to call home. Morishige says the group wants to design permanent housing that would foster community relationships – communal housing similar in some ways to Kahauiki Village.

James Pakele, a Waianae resident who volunteers with Pu‘uhonua, says their idea is to create a modern-day kauhale, a group of houses with communal bathrooms, showers and kitchen – which would help keep costs down. The kauhale would provide permanent homes and long-term stability for Pu‘uhonua’s 200 to 250 residents, who would pool their resources to pay for the village’s operating costs.

The plan is for the village to also contribute to the wider community. Pakele says one idea is to plant ‘ulu trees that can feed the village’s residents and others in Waianae. Another idea is to certify the village’s kitchen for commercial use so nearby catering or food truck businesses can use it.

The group has identified a few properties in Waianae and is trying to raise $1.5 million to lease or purchase a site – preferably one with existing infrastructure, Pakele says. If the plan works, it could be a model for others, he says.

In Kona, Hawaii County is working on creating Village 9, a 35-acre parcel with affordable rental housing and facilities for the homeless, says Roy Takemoto, executive assistant to Mayor Harry Kim.

The homeless facilities portion of Village 9, he says, will be an evolution of Camp Kikaha, the temporary site the county created with canopy tents, portable toilets and a shower in August 2017 to house about 30 homeless people who had been swept out of the Old Kona Airport. The camp closed in March after the expiration of the county’s emergency proclamation that allowed it to operate outside of zoning, building and fire codes.

“We were very lucky. Everybody in Hawaii was so giving; that’s how we were able to pull this off.”

– Lloyd Sueda, Project Architect, Kahauiki Village

Takemoto says the plan is to build an ohana zone on 5 acres of Village 9 as soon as possible, using temporary structures – such as fire-resistant tents or quick-build, low-cost structures like domes. Later, the county plans to replace the ohana zone with permanent homeless facilities spanning 15 acres of the property. Permanent facilities would include an assessment center, cottages clustered around open spaces and permanent supportive housing for chronically homeless individuals. The county hopes some of the homeless residents will get enough resources to afford and transition into the state-operated affordable rental project, he says.

As with Puuhonua o Waianae and Kahauiki Village, Takemoto says, the idea is to better integrate the homeless with the community. Village 9 will be located next to a future regional park and near the West Hawaii Civic Center. He hopes to have community members and organizations teach Village 9 residents skills in homebuilding, growing and prepping food, and financial literacy. In addition, he hopes to have nearby employers provide job training.

Lloyd Sueda, center, says he and other project leaders are getting inquiries from other communities about how they can create something similar. | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

So far, the county has received $184,000 in state money to start planning, which includes creating a master plan for Village 9’s homeless facilities and affordable rental project.

“This would be quite a test for us. … I think there are a lot of people who want to help,” Takemoto says. “I think the majority of the community just doesn’t want to see them around (living on the streets). So hopefully there’ll be a better understanding of the various situations that cause homelessness.”