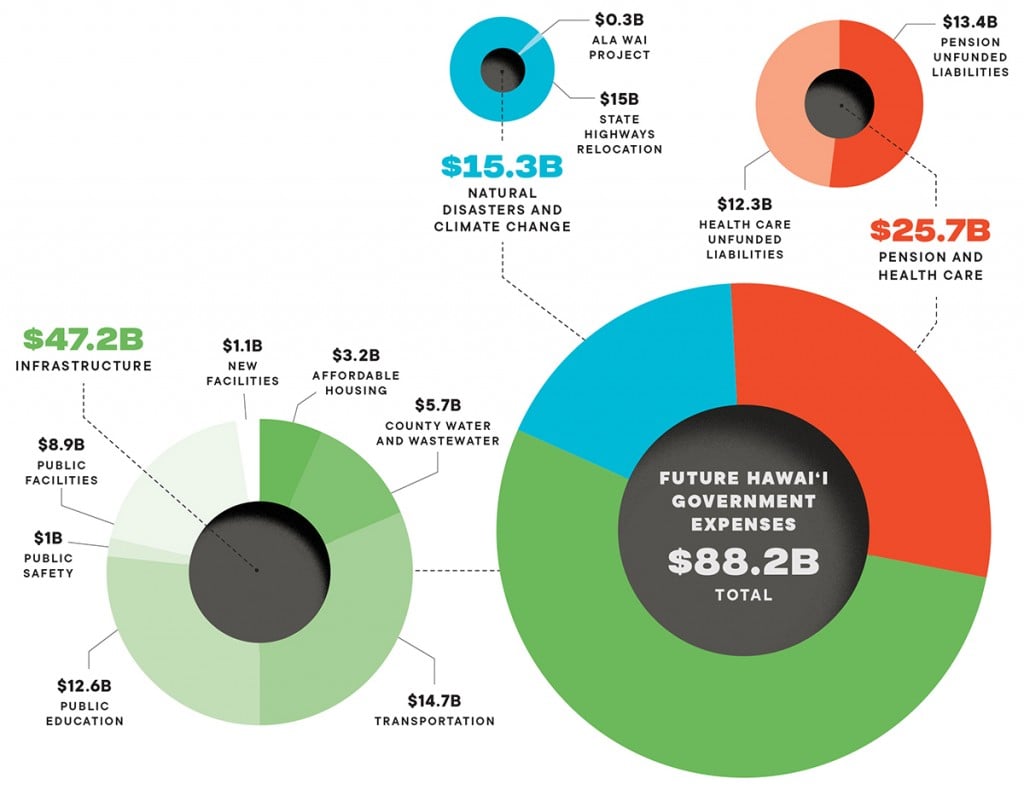

Hawaiʻi’s Future Liabilities are Expected to Cost $88 Billion

$88 Billion is the estimated liabilities for state and local governments over the next 30 years on infrastructure, pensions and climate change. We explore three broad options to pay these liabilities: increase government revenues, reduce government spending and grow the economy.

Hawai‘i is in a deep financial pit. Projects to mitigate climate change, improve infrastructure and meet public employee pension and retiree health care obligations are expected to cost the state and four county governments over $88 billion over the next 30 years, according to a report called “Troubled Waters: Charting a New Fiscal Course for Hawaii,” produced for the Hawai‘i Executive Conference.

That cost exceeds Hawai‘i’s 2018 real GDP of $80.8 billion and is five times larger than the state government’s operating and capital improvements program budgets for fiscal year 2019-2020.

“We need to sound the alarm,” says Keli‘i Akina, president and CEO of the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii.

The situation is critical but not hopeless, says Carl Bonham, executive director of UH’s Economic Research Organization and an economics professor at UH Mānoa. He was a contributor to the report and says these problems are solvable and the state is already taking steps to address many of the issues outlined in the report. For example, the state has agreed to gradually pay off its unfunded pension and retiree health care liabilities, which are expected to cost $25 billion over the next 30 years. In addition, state and county governments address some of their infrastructure needs every year, and some projects mentioned in the report already have federal or state funding sources.

There’s no room for backsliding, he says, and the key is to act sooner rather than later.

“We’re in this situation because we didn’t address many of these issues five years ago, 10 years ago, 20 years ago, 30 years ago. … So the discouraging part, if you will, is that we’ve known about climate change for quite a while, we’ve known about the needed infrastructure investment and we’ve chosen year after year not to maintain various pieces of infrastructure, not to invest in it,” he says.

It’s hard to get a straight answer on how exactly to pay for these expenditures. Contributors to the “Troubled Waters” report and other experts emphasize that finding solutions will require conversations and collaborations with stakeholders, but generally there are three options: increase government revenues, reduce government spending and grow the economy.

“Those are political choices and society has to be able to weigh in on that and … clearly in today’s world, the community has to buy into it,” Bonham says, adding that people need to be willing to make trade-offs. “And those trade-offs need to be equitable and need to be spread across society and not just borne by one group, usually the poorest among us.”

Here’s how much state and local governments are expected to spend on projects to mitigate climate change, improve infrastructure and meet public employee pension and retiree health care obligations over the next 30 years:

Hawai‘i’s Next Challenges

The $88 billion figure in the “Troubled Waters” report includes $15.3 billion to prepare for the impacts of climate change and natural disasters, $47.2 billion to improve critical public infrastructure and $25.7 billion to meet the state’s pension and retiree health benefits obligations.

The goal of the report was to provide a framework for the next set of challenges that Hawai‘i will face and ignite a process for the best and brightest in government, the community and the private sector to discuss how to address them, says Jeff Laupola, project lead for the report and a real estate private equity intern at Tradewind Capital Group.

He adds that the $88 billion figure used in the report is a conservative number. Estimates by government agencies were taken at face value and individual items had to surpass $100 million to be included. In addition, some government agencies may not have determined all of their future needs at the time the report was created. Sterling Higa, one of the report’s principal authors, adds that newer reports on climate change mitigation efforts have since been published and may add to the $88 billion.

State Rep. Sylvia Luke, chair of the state House Finance Committee, says the report makes it seem like the state needs a one-time cash payment of $88 billion, but that’s not true. For example, the Legislature appropriated $350 million in 2019 for the redevelopment of Aloha Stadium, and the Honolulu rail will be partially funded using federal dollars. Both projects were included as liabilities in the report – including the $1.55 billion the federal government has committed to the rail.

“They look at all these various funding as just one-time cash payment, and so when you simplify an issue like that then it kind of misleads the public that the amount that we need right now is $88 billion in cash, which is really not true,” she says.

Tom Yamachika, president of the Tax Foundation of Hawaii and a report contributor, emphasizes that paying for the state’s investments is not a matter of bringing in more revenues; instead, it’s about reprioritizing what government does.

“I’m reminded of a quote that’s attributed to Steve Jobs of Apple,” he says. “I believe the situation was they were at a product development meeting, he was at the whiteboard, he was writing down a bunch of ideas that were being thrown around, and he said: ‘Hey, that’s great, we have 10 good ideas. We have resources for three. So what three are we going to be developing?’ In state government, it’s like the 10 good ideas come up, ‘let’s fund all 10.’ ”

Decision-makers, he says, need to start telling people “no.”

“Unfortunately, sacrifice is not easy, and change is not easy,” says state Sen. Donovan Dela Cruz, chair of the Senate Ways and Means Committee. “And I don’t believe that the state has done a good job at articulating the consequences of not making these decisions. And so that’s something that we’re going to have to work on.”

There’s no silver bullet to pay for these future liabilities, he adds.

“It’s not just going to be just fees and taxes, it’s not just going to be investments in certain industries, it’s not just going to be public-private partnerships,” he says. “It has to be a macro approach that’s going to be integrated, that’s going to be strategic and that’s going to include a lot of different parties. It’s too much to put on one department or even just a couple of departments.”

Here are some potential ways to fund Hawai‘i’s future liabilities.

What About Raising Taxes?

There’s disagreement about whether taxes should be raised to help pay for Hawai‘i’s future liabilities.

Several experts interviewed for this story agree that raising taxes would be risky because people are already leaving the state as a result of the high cost of living and tax burden.

Keli‘i Akina, president of the Grassroot Institute of Hawai‘i, argues that taxes should be lowered. Hawai‘i has the nation’s greatest sales tax burden, which means, compared to residents of other states, a greater proportion of Island residents’ personal incomes are going toward sales taxes. He says Hawai‘i also has the highest estate tax in the country, and that several taxes have been raised recently. Examples include a higher surcharge tax on rental cars and increased property tax rates for hotels and homes valued over $1 million in Honolulu. Reducing taxes, he says, tells businesses and new residents that Hawai‘i is a place where businesses and individuals can thrive.

The general excise tax is a common target for proposed tax increases. Carl Bonham, executive director of UH’s Economic Research Organization and professor of economics at UH Mānoa, says raising the general excise tax would make the most sense from an efficiency standpoint because it also applies to the state’s nearly 10 million visitors.

The excise tax rate is relatively small compared to some states’ sales taxes. On Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i Island and O‘ahu the rate is 4.5% and in Maui County the rate is 4%. Revenue from the 0.5% surcharge on Kaua‘i and O‘ahu is used for transportation infrastructure. Bonham adds that the state has enough infrastructure needs for the surcharges to continue permanently. Hawai‘i already invests in its infrastructure every year, but more funds are needed to address long-term maintenance and new needs related to climate change, he says. However, he acknowledges this tax can be regressive because lower income people spend a higher percentage of their income on it than middle-class and affluent people.

State Rep. Sylvia Luke says she supports tax policy that is fair and equitable – where all segments of an industry are taxed. Taxing real estate investment trusts would be a fair tax policy, she says, because the trusts are currently sheltered from paying corporate income taxes while other local real estate businesses are not. “When we’re talking about billions of dollars of revenue that is needed, tinkering with a few taxes here and there is not going to do the trick,” she says. “In order to address all these problems and have it fully funded, then you actually are talking about a substantial number, amount of taxes that we need to raise.”

1. Reform the Public Pension and Retiree Benefits Systems

Public employees expect to receive their pensions and retiree health care benefits when they retire, but in 2018, the state’s pension system was only 55% funded and the health benefits system was 16% funded. If paid now in a lump sum, it would cost Hawai‘i $25.7 billion to fully fund these two systems and be able to pay for future retirement benefits already incurred for existing employees.

The Aloha State is gradually paying off these unfunded liabilities through annual contributions. While fully funding the two systems has perks, like better credit ratings that lead to lower borrowing costs for government and reduced contributions that taxpayers would have to pay in the future, it also means tying up more of the state’s limited general funds, leaving less money now for other programs like public education, safety, and health and social services. In fiscal year 2020-2021, contributions to the state pension and retiree health benefits systems (to cover the costs of benefits already earned and pay down the unfunded liabilities) and other fixed costs like Medicaid payments and debt service will make up about 51% of the state’s general fund expenditures.

To help mitigate future pension costs, the state introduced a new tier of reduced pension benefits for employees hired after June 30, 2012. Thomas Williams, executive director of the state Employees’ Retirement System, which manages the state pension system and serves 135,000 members, says those newer employees are required to work longer in order to vest their benefits, have reduced annual automatic cost-of-living increases added to their pension payments, have higher employee contribution rates and cannot use overtime in their retirement benefit calculations.

Wes Machida, former state budget and finance director and former ERS executive director, says savings from establishing this second tier of benefits, plus other reforms like increasing the amount of money that public employers have to contribute toward the pension each year, is expected to save billions of dollars. Williams adds that the new tier represents about a third of ERS’ membership and about 8% of its total liabilities and potential savings could be impacted by employment rates and turnover, payroll growth, inflation, longevity, retirement rates and investment return assumptions, among other things.

Changes have also been made to the state Employer-Union Health Benefits Trust Fund, which provides health and life insurance benefits to state and county employees and retirees and their dependents. Public employers help pay for benefits for both retirees and their dependents if the retiree became a member of the state retirement system before July 1, 2001. For those who became members after that date, employers only contribute toward retirees’ benefits.

Luke says the state has made significant strides to cut costs, but the challenge is that some of the savings won’t be realized until after those newer employees retire, which could be decades from now.

“One of the things that we are doing is this is really about looking out for the future generation and we need to make those tough choices now so that our kids and our grandkids won’t be saddled with some of the decisions that we make today,” she says.

Several people interviewed for this story agree that further retirement benefit reforms are needed. Making changes, however, is not simple. The state Constitution protects benefits that have already been accrued, so changes to benefits can only apply to new hires. “It’s going to take a while for the effect of any pension reform or benefit reform to kick in, but we still got to do it,” Yamachika says.

Williams says one potential pension change includes reducing or suspending annual cost-of-living increases when adverse events increase the unfunded liability. This is one way other states have addressed their unfunded pension liabilities, he says.

He adds that while prior earned benefits are protected by the Constitution, it’s believed that benefits attributable to future service can be modified, even for current employees, though this view has not been tested in Hawai‘i courts. Another potential option, he says, is to prohibit the use of overtime in future retirement calculations for employees hired before July 1, 2012. This would eliminate the practice of “pension spiking,” where employees work a lot of overtime in an attempt to increase their pensions. Machida adds that employers are already required to pay for pension spiking from their budgets. This was mandated several years ago to encourage employers to manage overtime and other pay more effectively.

Williams says the Legislature establishes the parameters of the retirement benefit plan and none of the possible changes he mentioned are now part of a legislative proposal. “We are constantly looking at alternative responses to reduce and mitigate our unfunded liability,” he says, “but it’s like having a menu of options, and there can be one or more combinations that achieve the desired financial impact, and that’s a subject of negotiations with the Legislature and the employer and employee groups.”

Derek Mizuno, administrator of the EUTF, wrote in an email that the EUTF board of trustees is addressing its long-term liabilities in several ways. The board puts out a request for proposals every few years for health and life insurance providers and third-party administrators. This helps to ensure that it’s getting the best prices for retiree premiums, he wrote. In addition, benefit plans are designed to maximize other insurance and subsidies, like Medicare, and encourage healthy and beneficial behaviors through the provision of diabetes prevention and supportive care pilot programs and the removal of copayments for annual exams and advance care planning visits.

While the state has a plan that puts it on track to fully fund its pension and health care obligations within 30 years, Machida cautions that the plan is based on numerous assumptions, such as how long people will live. If those assumptions prove incorrect, it will change the state’s retirement costs.

Akina of the Grassroot Institute argues the pension system should be replaced with a defined contribution plan, where benefits would be provided based on retirement fund contributions, rather than years of service and salary. That’s how 401(k) plans work. However, some people, including Williams, argue that such a transition would be more costly. The defined contribution plan would add an additional administrative cost because the state would still be obligated to honor existing benefits for those who choose to remain with the defined benefit plan and would still need to pay off the unfunded liability, says Beth Giesting, director of the Hawai‘i Budget & Policy Center, an affiliate of the Hawai‘i Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice.

“If there is ever a benefit in having a defined contribution plan, it is so many years in the future that nobody has even looked at whether it’s a good thing,” she says. Colbert Mastsumoto, who served on the ERS board of trustees from 2000 to 2017 and was a principal author of the “Troubled Waters” report, adds that it might be an option to look at after 2043, when the pension is fully funded.

Giesting says Hawai‘i should continue to pay off as much of the unfunded liabilities as it can because it lessens future costs for taxpayers, but the state doesn’t need to fully fund its pension. Funding the pension at a lower level, she says, would give the state flexibility to do other things, like prepare for the next recession or fund other critical programs.

Williams says retirement benefits support citizens in their golden years and the overall economy. Retirees supported by pensions tend to not need public aid, he says, and if the pension were eliminated, it would be a “huge financial and societal mistake.”

Randy Perreira, executive director of the 42,000-member Hawai‘i Government Employees Association and president of the Hawai‘i State AFL-CIO, adds that Hawai‘i’s pension plan is one of the best in the country and helps government compete for employees. “Frankly, the way we view it … the pension plan is the benefit that government employees get for being paid far less than their private sector counterparts over a 30-, 40-year career,” he says.

Is Declaring Bankruptcy an Option?

The United States Code does not allow states to declare bankruptcy, says Tom Yamachika, president of the Tax Foundation of Hawaii. Municipalities, however, can declare bankruptcy. Detroit, for example, declared bankruptcy in 2013 after facing billions of dollars of debt and ended up reducing its pension and health care benefits, despite Michigan having a constitutional provision similar to Hawai‘i’s that protects accrued retirement benefits.

In a 2018 paper published by the Congressional Research Service, Kevin Lewis, a legislative attorney, wrote that bankruptcy courts presiding over municipal bankruptcies, like those in Detroit and Stockton, California, have agreed that municipalities can reduce their pension debt in bankruptcy. Many municipalities, however, have opted to leave their pensions intact.

Bankruptcy for the state is an unlikely option, several people interviewed for this story say, because Hawai‘i’s situation is nowhere near that dire.

2. Form Public-Private Partnerships

Sherry Menor-McNamara, president and CEO of the Chamber of Commerce Hawaii, says the “Troubled Waters” report highlights the need for businesses to work more collaboratively with government.

“We need to start talking with each other and finding out what can we do to solve some of these challenges now because we are at a crossroads,” she says.

Several people interviewed for this story agree that government should partner more with the private sector to complete some of its critical projects. Some plans are in the works to use public-private partnerships, or P3s, for the last segment of the Honolulu rail, and to redevelop Aloha Stadium into a new commercial district with a smaller stadium.

Jill Jamieson is the managing director of real estate services firm JLL and author of a report commissioned by the Ulupono Initiative that looked at finance and delivery options for the Honolulu rail project. She defines a P3 as a broad range of medium- to long-term contracts to design, build, finance, operate and/or maintain public purpose infrastructure. The last part is key to her definition, she says: A P3 is a procurement tool for delivering an infrastructure project that a government would otherwise do itself. In addition, some risk – such as financial or scheduling – is transferred from the public sector to the private partner.

One of the challenges with getting people on board with using this tool, she says, is that a P3 is not well defined in Hawai‘i. Andrew Robbins, executive director and CEO of the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation, says any type of contracting between government and a private company could essentially be considered a public-private partnership, but what P3 infrastructure projects have in common is some private financing. P3s, he adds, can also be used on social infrastructure projects, such as the building of hospitals, student housing and convention centers.

HART and the City and County of Honolulu are jointly soliciting proposals to design, build, finance, operate and maintain the final 4.1 miles of the rail from Kalihi to Ala Moana Center. Construction work is estimated to cost around $1.4 billion. Robbins says this delivery model provides greater certainty regarding the cost to taxpayers and the schedule because the private partner will finance the construction.

“This means that while they’re constructing the project, we don’t pay them full value of the work they’re doing,” he says. “They have to finance a portion of it themselves. And only after the project is completed and the train is actually up and running according to the performance standards in the contract, do we, the government, public sector, start to pay back the private finance.” That way, he says, the private partner has a powerful incentive to finish the project on time and on budget.

The 20-mile, 21-station rail project has faced ballooning costs amid years of construction delays. The project, which is being funded by the general excise tax, transient accommodations tax and federal funds, is now expected to cost about $8.16 billion. HART and the county anticipate that the contract to design, build, finance, operate and maintain the final segment of the rail project will be awarded in February and construction is expected to begin in September. The entire rail system is forecast to be operating by December 2025.

Akina cautions that P3s need to be structured carefully to ensure there’s benefits for the public and private entities and taxpayers. A good public-private partnership, he says, is one in which the business entity, not the taxpayer, takes some of the financial risk so the business is incentivized to ensure construction and ongoing operations are profitable. “Where that’s not done, the taxpayer is often left holding the bag for the liabilities of a failed project,” he says. “We can learn a lot about this by looking at the rail project.”

Robbins says there’s great interest in P3s in Hawai‘i and many eyes are on the rail to see how the public-private partnership plays out. Perreira of the HGEA anticipates that P3s will be used for transit-oriented development along the rail line, too.

“It can work, but it’s not the answer in all situations,” he says, “and it shouldn’t be viewed as the end-all solution to government revenue issues.”

3. Grow the Economy

Bonham, the economist, says Hawai‘i needs a sociopolitical consensus that it will do everything it can to have sustainable, equitable economic growth. And that growth, he says, needs to be reasonably strong.

“Not what we think is likely to happen over the next three or four years, which is very anemic growth,” he says. “There’s a huge difference in our ability to cover these expenses if we’re growing it 2% or 2.5% instead of 1%.”

One way to accomplish this is to improve the regulatory environment for businesses. Bonham says entrepreneurs should be able to create and expand businesses without facing obstacles at every turn.

Gladys Quinto Marrone, CEO of the Building Industry Association of Hawaii, wrote in an email that the long time needed to obtain permits and other approvals is a significant barrier to construction businesses. “It’s not just one regulation,” she wrote. “It’s a cumulative effect from multiple government agencies imposing their own regulations – death by a thousand cuts.”

Hideo Simon, co-owner of Square Barrels restaurant and Pint + Jigger, says he struggled to navigate the complex permitting process to open his restaurants in Downtown Honolulu, both of which required renovations to spaces in existing buildings.

Renovations for Square Barrels included changing the gas cooking equipment, moving the dish pit and adding walls. Any changes required approvals by several government offices, including the permitting, fire, wastewater and sanitation departments.

“The problem that I think for somebody like me or small businesses in general is that we’re trying to create something from scratch and we’re trying to be energetic and enthusiastic about our craft and what happens is we get thrown into this big matrix of regulation and have to figure out how do we guide ourselves through this labyrinth and try to get to where we’re trying to be,” he says. “So, like, from the time that I signed the lease until the time I opened, it was approximately nine months.”

The biggest risk in dealing with the time-consuming and expensive process before you actually open the business, he says, is that rent, utilities and employee costs still need to be paid when there’s no income coming in.

He plans to open another restaurant in Kaimukī in 2020 and says he’s expecting the permitting process for renovations to again take a long time. More education and good communication from government agencies can help, he says, especially in understanding what regulations need to be followed and what steps small businesses can take to save money.

Bonham says government agencies need to be familiar enough with business models and industries so they can analyze whether regulations can be improved without putting things like the environment, health or safety at risk.

“That needs to be the attitude or the whole approach,” he says. “Yes, we got to make sure we protect the environment, but we also need to try and make sure we’re not creating years of red tape or high cost burden. And if that becomes the attitude of every line agency that’s interacting with businesses, then I think we’re making steps towards having a business environment that is more conducive.”

In addition, he says, Hawai‘i needs more policies that facilitate investment in businesses and industries. One successful example is the Hawai‘i Growth Initiative, a state equity investment program that was launched in 2011 by the Hawaii Strategic Development Corp. A 2016 UH Economic Research Organization report found the initiative successfully catalyzed the development of an innovation economy by helping to launch companies, entrepreneurial programs and coworking spaces in the Islands. The report estimated that for every dollar invested into the program by the state, local innovation companies received $11.49 in funding.

Yamachika adds that some people in Hawai‘i mistakenly believe that business is evil, and that mentality has to be worked on. Businesses, he says, need to show people that they’re trying to help.

“There’s got to be I think a deeper understanding that needs to be forged between the business community and government to address some of these very real problems we have,” he says, “and I think the Hawai‘i Executive Conference’s report is a very important first step to at least start identifying what we have to look at and then maybe using that as a catalyst to get people together to start talking about it.”