How to Lead

To learn about leadership in Hawaii, Hawaii Business senior writer Dennis Hollier interviewed seven of the state’s most powerful and effective leaders, past and present. Among the questions he asked:

- What are the key attributes of great leaders?

- How do great leaders deal with crises?

- Are leaders obligated to prepare for transitions?

- What advice do you have for young leaders?

- Which leaders do you admire?

Most successful leaders have thought deeply about these kinds of questions, so we weren’t surprised that their responses were articulate and perceptive. What did surprise us was how their individual comments wove around common themes. Even though they were interviewed separately, it sounded like they were listening to and enlarging upon each other’s insights. It sounded like a conversation.

That’s how we are presenting the remarks of these seven leaders: George Ariyoshi, John Dean, Walter Dods, Mark Dunkerly, Constance Lau, Kathryn Matayoshi and Colbert Matsumoto. For continuity and clarity, we moved some of their comments around, deleted some repetition and edited for conciseness. That said, these are their words in their proper context.

In next month’s issue of Hawaii Business, we’ll share the insights and personal stories of two uniquely Hawaiian leaders, Nainoa Thompson and Harry Kim.

Let’s start by talking about what you think are the key characteristics of great leaders?

Dods: There are lots of different kinds of good leaders – and I’ve made leadership a study of mine for a long time. They come in all shapes and sizes. Some people lead by fear and intimidation, and some of those leaders can be effective, but usually not for the longer term.

The kind of leaders I admire the most are the great communicators, collaborative leaders who are still willing to make hard decisions themselves when they have to, but are willing to get input, and are able to motivate others and get the job done, and, in the end, everybody thinks they accomplished it together. These are all trite sayings, but really true in the end.

You have quiet leaders who lead by example. A great example would be Stan Kuriyama at A&B, who’s very soft-spoken and quiet, but very effective. Then, you have people who are strategic visionary type leaders, who really have a vision and get people to buy into that vision, and through that, get the job done.

Lau: I would say strategic vision is the key quality of leadership. For me, strategic vision is the ability to see what others don’t see, to be able to look at very complex, difficult problems and figure out very simple, elegant solutions. Then, the second part of leadership is that you can inspire other people to believe in and follow you in the execution of that vision. And that’s not an easy thing to do. There are lots of smart people around, but those who have a clear vision and translate it so others want to follow – that’s where you get leadership.

Matayoshi: I agree, it’s important that a leader have the ability to express a vision that inspires. Earlier in my career, I saw that with Cliff Jamile, who was the manager and chief engineer of the Board of Water Supply when I was there. He said the mission of the BWS had changed from one of being an organization that delivered water – pumped it up, pumped it out – to one in which we were all stewards of the water for future generations. Shifting to that focus was inspiring; then, it raised all kinds of questions about sustainability. This was long ago. To me, that’s one characteristic of leadership – to see something and express it in a way that inspires and sets a direction. That’s important for a leader.

Another thing, I think, is that good leaders are constant learners. You learn from every experience you have. You learn from your successes, you learn from the obstacles and you learn from your failures. And you’re open to that learning. In the old model of leadership, you thought you knew what to do and you told everybody and that was it. But, to me, the new model of leadership – or at least the model that works in this constantly changing world – is that you’re always learning something new and looking at how you can apply that new knowledge to adjust and adapt.

The third element of leadership is really about understanding people, trying to find the right place for every person on your team, a place that meets their skills and talents. This is true in any organization, but it’s certainly true when you’re going through significant transformations, as we’re going through at DOE. People who were good at their old jobs are not necessarily good in the new world. It doesn’t necessarily mean they’re not valuable; you just have to find the right place to make use of their talents. Part of being a leader is not throwing everything out and wishing you had something better, but trying to unite a group of diverse people around a common mission, and have them realize that, whatever their talents, they can contribute toward that mission.

Dunkerley: Among effective leaders, there are various types, but some things are pretty common. You want a leader to have a sense of vision, a sense of direction; to have the ability to manage for the short term while, at the same time, looking at the long term and recognizing the innate tensions that exist between them, and having the strength of personality to work through those things. That’s a common area where people fail as leaders.

It’s both being able to marry a strategic outlook with the practical day to day. In all organizations, you have some people who are really gifted strategically, but who are uncomfortable in managing the unexpected day-to-day problems. Then, you have people who, by nature, are great at addressing the issues in front of them, and get absorbed by them, but don’t spend time thinking about the broader direction. To be a leader, you need both skills.

Dods: But you can’t have five CEOs, or even two CEOs. Citicorp is the greatest example, when Sandy Weill and John Reed put the companies together and tried to be co-CEOs. That lasted for about 90 seconds. I could give other examples, but, in the end, you do need a leader, somebody to call the shots. But a leader needs to live with the good and the bad and take the hard knocks.

We seem to agree that leaders must have good communication and collaborative skills, and strategic vision, but what do those characteristics look like in practice?

Lau: I’ve been in many situations where we had to conceive of something differently. A very simple one was when I was at Kamehameha and people were very worried because the IRS was after the tax-exempt status of the estate. The IRS felt the trustees were not following the trust’s charitable mission, and you only get the benefit of tax exemption if you spend money on charitable purposes. People were worried the so-called “Bishop Estate” was overwhelming the work of Kamehameha Schools, which should have been the real mission of the trust.

So we renamed the financial side of the trust as “the endowment.” Of course, it’s not technically an endowment; it’s a trust estate. Those are very different legal entities. Changing the terminology, though, and calling the estate an endowment, even though it wasn’t, changed the whole juxtaposition of the financial side of Bishop Estate and Kamehameha Schools. All of a sudden, people could better understand that the mission really was about the schools and the education of Native Hawaiians and the improvement of the well being of Native Hawaiians through education. That was the real purpose of the trust – not the management of the assets.

Another example was when I went to American Savings Bank. Remember, at the time, it was a pretty simple savings and loan that took in savings accounts and made single-family-home mortgages. When I looked at it, it seemed like a tremendously underutilized asset for the community, an asset that could bring a whole lot more value to everyone around if it broadened the products and services it offered. So, we began building a commercial banking operation that could help businesses. We also brought in products for consumers. So, instead of only having savings accounts, we started offering checking accounts and credit cards. Instead of just mortgages, the bank has been the No. 1 producer of home equity loans, which is a new product we rolled out. We were the first in the market with remote capture for the deposit of checks using mobile devices. It’s about having the strategic vision to look at something with a new pair of eyes and see much greater potential, and much greater value and make much larger contributions to the community. That’s one of the key aspects of leadership.

Of course, you’ve got to be able to sell people on it. Hopefully, that’s a lot easier. Because, if you’ve done the visioning correctly, and that visioning is all about bringing greater value to the organization, and making greater contributions, that’s really something most people

want to do in their lives. They want to do something of value; they want to contribute to doing something bigger than themselves. So, usually, when you describe your vision, the vision itself is very inspirational. But inspiration is different from motivation. I could motivate someone by offering to fire them. That’s not what leadership is about; it’s about inspiration.

Ariyoshi: Vision is very important. But more important is that the leader’s vision be not only his, but becomes the vision of many others, so they believe in it and it becomes a community effort. My effort on the state plan was a good example. I felt the state plan was important. It came about because, when I became governor in 1974, 15 years after statehood, I wanted to know what had happened in Hawaii in those 15 years. I found out we had tremendous growth. Our population had grown 2.5 percent per year, compared to the national rate of 0.8 percent. So, we were growing three times faster than the rest of the United States.

I looked at automobiles. We had 200,000 of them at the time of statehood; 15 years later, we had 500,000 automobiles – two-and-a-half times more. I became very concerned about this rate of increase. I thought to myself, “How are we going to provide educations to our children, provide job opportunities and social services – everything that we needed to do in our community?” That’s when I began to feel that, if we didn’t do something about this, it was just going to happen. Things were not going to come by chance. I thought that we ought to be able to identify the type of place we want Hawaii to be in 20, 25 years. The problem is that most of the time leaders look at today, this year, what are the problems, and try to solve those problems. They never think about solving them in the context of what’s going to happen 35 years into the future. That’s when I began to feel very strongly that we needed to look at the future, and ask, “What kind of future do we want for Hawaii?” That was the genesis of the state plan.

But the state plan should not be a future that I set forth. I could participate in it and say what I wanted to do, but I also wanted to encourage people to come sit with us and also think about it, so it became the vision and preference of many people thinking about the future. That’s what the state plan was all about. We had hundreds of people come together and talk about each of the 12 functional plans. That’s why it became not my plan, but your plan.

A friend of mine recently reminded me of a quote by Lao Tzu: “A leader is best when people barely know he exists; when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: ‘We did it ourselves.’ ”My friend said, “You remind me of that quote because you never try to be remembered as the leader. You involve people and make them feel like they want to participate.”

How does a leader motivate people to take that kind of ownership?

Ariyoshi: No. 1, you have to be willing to do it. There are some people who say, “Come work with me; but it’s going my way, not your way.” When you do that, you limit yourself to one person’s ideas – yours.

For example, we have a lot of boards and commissions in Hawaii. When I appointed board and commission members, I wanted to make sure we created a diverse board – people from different parts of Hawaii, people with different cultural and occupational backgrounds – so we would have a vast diversity of people and ideas. I participated in boards and commissions and I always told every person, “You are different from the people you’re sitting with on the board, and that’s by design. I want you to be able to speak up and put your thoughts on the table.” That diversity of thought must come out. I don’t want the board or commission to be lead by one strong person who feels that he or she has a monopoly on good ideas. I want all the thoughts on the table. That gives us the best package of ideas to select from.

But many leaders don’t feel that that way. They feel they know everything, they have to have things their way, and anybody who works with them has to do it their way or don’t come work with them.

That gets to the question of what personal attributes – as opposed to tactics or strategies – are most important to be a successful leader?

Matayoshi: A lot depends on what kind of organization you’re in and what stage it’s at. I’m a big believer in the idea that organizations need different kinds of leaders depending on the challenges they face, where they are in their life cycles. You have startup organizations, developing organizations, mature organizations, failing organizations. A small startup with a handful of people and a great idea needs a different kind of leadership from a large government entity that’s been around for a long time and has lots of traditions.

Dean: I don’t think there’s one description of a CEO. There are many styles of leadership. You don’t have to be an extrovert or an introvert, for example; or, by Myers-Briggs, a thinker or a feeler. Male or female – it doesn’t matter. The attributes you start with are core values. Does this person have the values that will reinforce the culture you’ve built? So, it’s more a cultural question for me. You want that person to be the heart and soul of this organization.

For example, at CPB, we have a lot of excellent teamwork. It’s team-focused leadership. How people treat one another here is a very important part of our values. It doesn’t matter how good you are, if you accomplish your goals, but, in the process, you attack and destroy our culture, you won’t be a survivor here. You need to do it with teamwork and within our culture.

Matsumoto: One really important characteristic in a leader is courage – the courage to take risks, to try different things, to be willing to deviate from the pack. Otherwise, if it was easy to lead, then everybody could be a leader.

The other aspect of leaders is, typically, they tend to be very self-confident people, people who sometimes have pretty big egos. A really exceptional leader is one who has a good grasp of how interconnected and interrelated organizations are, whether it’s a company, a government agency or a community. I think a good leader understands that he or she really is just one part of the whole that enables whatever initiative is being undertaken to become successful. In other words, good leaders are not necessarily people who will say, “I did this, and I did that,” without really appreciating other people and other factors enabled their success.

Dods: Leaders also need to be humane, even when making tough decisions. The main skills are: communication, humaneness and the ability to listen. That last one is overlooked quite a bit. Leaders, after a while, start thinking they know all the answers. That’s easy to fall into, because everybody starts kissing your ass and telling you how great everything is because you’re the boss. Once you start buying into that, you’re dead as a leader.

You’ve got to be able to listen, and to change your opinion when people offer better ideas. That’s not easy to do, but a really good leader will say, “Yeah, I felt really strongly about it, but after listening to your arguments, you’ve convinced me that’s a better direction. Let’s go

that way.”

Dean: Part of leadership is also not taking yourself too seriously. I have this disease called “CEO-itis.” Once you’re a CEO, there’s always someone who’s going to want to tell you how great you are, what a wonderful job you’ve done, what a beautiful speech you’ve made. There’s huge risk in that. When I give talks on leadership to young CEOs, I warn them of this disease, CEO-itis: Don’t believe everything you hear.

It’s said that, when a Roman general returned to Rome in triumph, a slave supposedly rode in the chariot with him, whispering in his ear, “You’re human, you’re human, you’re human.” What I take that to mean is: Don’t believe everything you hear. You’re not as great as they’re saying you are. Leaders need to have that machine in their head that discounts flattery if they’re going to avoid the disease of CEO-itis. I’ve seen so many young stars get it. The earlier they get it, the bigger the danger, because they think it’s all about them.

Dunkerley: One of the things that I feel very passionate about is that good leaders have an innate ability to recognize and to put themselves in the position of the people they’re dealing with, to step out of their own self-interest and to make the calculation around, “Why is this issue coming out, what are the motivations behind it.” That’s how some introverted leaders can be very effective. And that can be a limitation for some extroverted leaders. There are extroverted people who have a terrific innate sensitivity to other people. But tone-deafness around that is a terrible Achilles heel.

The second you think it’s all about you – where you’re in a meeting and the sieve through which you’re pushing all the information you receive is one that just contemplates your own viewpoints, your own interests, without considering what other people in the room are thinking and why they’re thinking it, why that makes sense to them but doesn’t make sense to you – these are obviously tremendously important skills. It’s empathy.

My first boss, who remains to this day perhaps the most significant influence on my career, was a real firecracker. He had a very strong personality. He moved a mile a minute. In fact, he moved so quickly that there wasn’t much structure to the way in which we’d do things – which sounds like a bit of a disaster. But, at the same time, he was super bright. He’d push you right to the edge where you’d just want to throttle him. But he had an innate sense of when that point had been breached, and he would kind of acknowledge it and shine his affection on you right at the point when you were just about to wring his damned neck. Paradoxically that really bound you to him. He had that innate empathic sense, and, for those of us who worked very closely with him, he was actually terrific.

I had another boss who was terrific because he had working for him a number of people who were moving up in the organization and were very ambitious – I was one of them – and rather than try to corral us, he embraced that and saw his role largely as supporting our initiatives with people higher up the chain of command, so to speak. These were very different types of people, but I enjoyed working for both of them because they both looked at the broader situation and they both had that innate sense of what was important to other people. In fact, one of the things I say to people who manage others, is you really ought to have a sense of what the hot buttons are of the people you’re working with. They’ll be different for different people, but, aside from getting the work done, if you can’t answer the basic question, “What’s important for the people that report directly to you?” you’re not really very perceptive.

Matsumoto: Leaders develop skills over the course of their lives. The important things are: Do they have an appetite for taking risk? Do they have the ability to see things from a strategic perspective? Do they have the willingness to sacrifice their own personal time and comfort for the benefit of the group? Do they have the sensitivity to really appreciate and understand the people they’re enlisting in whatever effort they’re undertaking so they can also express a degree of gratitude for the contributions that others are making to the success of their effort?

Superintendent Kathryn Matayoshi at her office in downtown, Honolulu. Photo: Elyse Butler Mallams

Let’s talk about transition. Does a leader have an obligation to prepare his successors for leadership positions?

Ariyoshi: Personally, I have to look at how much longer I’m going to be around. If I don’t provide for succession and training so people can do the things that need to be done, there’s going to be a tremendous void when I’m gone. I feel very strongly about transition, about giving opportunities to other people so they can begin to take over and do some of the work the leader has been doing. I did that very recently. I was the head of PISCES, which is a space program. I decided it was time for me to step down while I’m still very able, so somebody else can begin to exercise leadership. So, I asked Henk Rogers whether he would be willing to take it over. He told me he was apprehensive about coming in cold, but I told

him I would be around to assist him to the extent necessary, so he’s the new chair of PISCES, and he’s done a remarkable job.

Part of leadership is not hanging on. It’s being willing to pass the mantle and to train other people – especially in an elected office, where you know you’re only going to be there for a short time. Under those circumstances, the person must be very cognizant that the things he or she feels very strongly about will be carried out by people coming on in the future. And not necessarily by their successor, but by the people who continue in government.

Dods: The thing I want to say is most important about leadership is that, when you leave the organization, if the person you helped select to replace you is not stronger, brighter, faster, better than you were, then you failed as a leader. If you have to go outside of your own organization to select your new leader, I think you’ve also partially failed. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t bring people in from outside the organization; but you should bring them in, and get them accustomed to the culture, and groom them, if you have to do that. But you should take internal candidates and do that, too. If a leader comes right to the very end and nobody in the company is capable of replacing them, and you have to go outside the company, that’s a mark that you haven’t worked hard to prepare the next generation of leadership and you’ve failed your own organization. Your ego is so big that you didn’t think it was important enough to have a replacement.

That’s where I see a lot of weakness in the leadership ranks in Hawaii. You can go through the companies in town and see which ones have strong No. 2s and which ones will end up importing leaders. There are times you legitimately need to do that, but they’re rare. Most of the time, it’s just an excuse because the company hasn’t done the hard work of identifying and producing leaders.

Matayoshi: If you want to sustain the changes you’re making, then you plan for transition and succession. The hardest thing to remember is that the next person is going to face a different situation from you. So, you don’t look for somebody who looks like you. You may even want someone who might not agree with you. That’s sometimes hard for leaders to see. A strong No. 2 may not always be the right person to lead the organization in its next iteration.

Dods: I was on the board of a company once, and I really admired the CEO. One of the things he’d do was once a year, he’d ask the leaders of every major division or department – the top 15 or 20 people – “Give me a list: If you got hit by a truck tomorrow, who would take your place? And, if you had the proper time to groom someone, who would take your place?” A lot of times, those are different people. One would be someone who could keep the company going as a stopgap for now. But, if you had two or three years, who would you see coming up? The second part of that question is, “What should you be doing to get that second list of people ready to assume leadership roles?”

The reason I got so involved in this whole question of succession planning is that I experienced it personally. This is going to step on toes, and people are going to get upset, but I think enough time has passed: We had a super-strong CEO, John Bellinger, who did a great job for the bank, but he thought he was going to be there forever. He thought nobody could replace him. So, when I took over – because he died of a heart attack or stroke, but he had passed the retirement age and stayed on – I was thrust into the job suddenly, without having those one or two years of learning things you don’t learn just coming up the ranks. Things like relationships with the board of directors, with the investment community, with outside groups, because you’re pretty much involved in learning the inside stuff. And I vowed to never, ever let that happen to my organization on my watch. So, early on as CEO, I got very involved in the leadership issue, seeing who needed what kinds of skills so they could be ready. And I practiced what I learned from the one CEO I admired, asking everybody to give me a letter once a year saying who would take their place if they got hit by a truck. Every year, those letters would change, and rightfully so. Every year, somebody else comes up the ranks, and you learn to get a much better feeling for them.

Those people would do this exercise as well: Each division guy would go down to his five section heads and ask them the same thing. And we’d keep that list and keep a big board of all those names and what skills they were missing. Should we send them to the Harvard Advanced Management Program? Should we put them in an operational job, if they’re in a lending job? Should we be cross-training them? Should we be giving them more skills at mentoring, which is very important, both for leaders and next-generation-leaders. We actually started informally putting mentors together with up and comers.

These are not easy things to do, because, if you don’t do them right, or people don’t handle them right, you get people going around with this “anointed” halo around their heads, and people can become jealous. So they have to be handled right and the chosen have to be humble. They need to clearly understand these things can disappear any time. But that’s no excuse for not doing them.

Dunkerley: One of the things I ask managers to do – what I’m looking for – is I think it’s every manager’s responsibility to manage themselves out of a job. If that’s personally, desperately threatening, they probably aren’t the right people to lead. The paradox is that people who work assiduously to manage themselves out of a job tend to be indispensable in an organization and move to the next level of promotion and development, while the people who are mindful to make sure they always have a job become the very people who, as you look at your organizational structure, you say to yourself, they’ve got to move along. So, there’s a real irony in it. But I expect all managers to work hard to make themselves redundant.

Dods: When it comes to succession planning, all pitfalls are minor compared to the crime of not doing it. I want to make that point clear, because you could use any number of reasons not to do it. The biggest reason people don’t do it is they feel insecure themselves, and they don’t want the board and/or the shareholders to know there’s a competent person to replace them.

When does this transition process begin?

Dods: Well, it’s never too late to begin. Let’s start there, because a lot of companies don’t do it. The day you become the CEO is the day you should start planning to groom your successor. The reasons are: One, you could get hit by a truck tomorrow. Two, it’s your obligation to the employees, to the community and to your shareholders to leave the company better than you found it. For those two reasons, it ought to start the day you’re named CEO, if not sooner.

Dean: I think transitioning starts with: How do I transition? For me, it’s delegating more. I have fewer direct reports today than I had a year ago. What I’ve told people is, “What you’ll see this year and next is we’ll transition more of the responsibility for the day-to-day operations of the bank to others.” So, it’s not going to be, you wake up one day and read the papers and see, “John’s left the bank and he’s back in Waimanalo and no longer working.” But, is it bad to fade away? I think, if you fade away, there’s a time when you empower, you trust. But, just because you empower and you trust doesn’t mean you don’t verify. Whether it’s me or the board of directors, you always need checks and balances to make sure we’re doing what we say we’re doing, and we’re doing it the right way with the right values.

Dunkerley: I spend a lot of time thinking about succession. At the end of the day, I don’t fly any airplanes, I don’t load any bags myself, I don’t check in the customers, I don’t work on any applications in the IT department. The success of Hawaiian Airlines as a company, and my personal success as a human being in the context of my life as CEO of the company, is determined by the effectiveness of everybody else in the company, and whether they have the tools they need to do their jobs, and have the right direction and motivation. So, succession and the development of talent within the company is something that’s front and center that I think about almost daily. The reality is, it isn’t me who makes this business successful; it’s everybody else. So, it’s a good use of my time – to think about how we can get the right people, give them the right tools and motivate them in the right way.

Some companies have a COO for the nuts-and-bolts operations, which leaves the CEO free to strategize and look at the bigger picture. Is that also a model for transition?

Dods: Sometimes it’s great training for the No. 2 person to do the grunt work of carrying out the mission as he’s developing his own ideas about the mission.

Matayoshi: Every visionary needs somebody who has the nuts and bolts in mind to make things happen. I don’t believe in planning and not taking action; there needs to be a bias toward action. That comes from a focus on outcomes and results. Plans don’t get you those outcomes, you have to be willing to take action.

What’s helped me is that I know the nuts and bolts, having been in state government for a while. It’s very helpful to understand the fiscal, the HR, and the IT issues and challenges of working in government systems. It helps you to be the problem-solver, and to facilitate the development of others as problem-solvers as well.

They’re not separate; you can have someone who’s a visionary, but who understands how it works, too. The dream has to be connected to the mechanisms that make the dreaming a reality.

For any succession plan to work, you need a cadre of people prepared to lead. Can leadership be taught?

Matayoshi: There’s actually quite a bit that can be taught. But I don’t think that you can teach the desire to lead. Not everybody wants to lead. There are some characteristics that make it easier to lead. One is that most really great leaders are reflective. They think about what they’ve done. They think about how something came out. Maybe it’s part of that continuous learning thing. If you have that nature, you’re going to be constantly looking for ways to improve and do it better next time. Again, a lot can be taught, but not the desire.

Lau: There’s a whole industry based on talent development and executive development. There are batteries of online tests that, much like the SAT test, measure things like your leadership style. Are you a participatory leader or dictatorial? How do you solve problems – i.e., what is your thinking style? Are you more intellectual about your analysis, or do you rely more on intuitive or soft data? What kinds of people and characteristics do you value the most? Do you value people who are more social, who have a higher EQ than IQ, or do you value the expert who’s strong in analytics? How high is your tolerance for ambiguity? When you try to solve problems, how much complexity can you deal with? It’s like the difference between playing a 3-D chess game versus a 2-D checkers game.

For other parts of the program, we look at the profiles of senior executives and ask, “What do they need to develop the full skill sets around the table?” Do they need more financial skills and to be rotated into the finance group? Do they need more line experience or operating experience? Then, part of the plan might be to rotate them into operations. Business is about people, so it’s important for them to learn how to develop the workforce. Maybe they should do a stint in HR or organizational development. It’s probably good for them to learn about contracting. In other words, you try to identify what skill sets would be desirable for them to have, and then rotate them through the positions that can give them the full panoply of skills.

Then, as they say, you only know if they’re ready if they’re actually given the jobs to do. So you put them in senior positions and see how they do. Sometimes, when we have to put somebody in a position that’s a stretch, we also try to design support systems, so there’s a senior person to mentor them. That was the benefit for me being at Kamehameha Schools with those very senior guys. We were actually doing it, leading the organization and making decisions, and I had these four very experienced guys who could tell me how they would do it.

What’s extremely valuable to remember is that leadership today is much more about running great teams. Therefore, as CEO, it’s really useful to have been in the shoes of the different members of the team. It’s really great to have been in the CFO slot, to have been in operations, to have been in the legal position. Then you have a much better understanding of the perspectives of each team member and that makes it easier to help the team craft the optimal solution to a problem. Hopefully, though, you’re also deep in at least one area – probably the track you came up through – but you also like to have the breadth to synthesize all those viewpoints.

That’s even more important in Hawaii, because, while in other places, the financial aspect would rule, here, you have to have a balanced solution. One major exception: You can’t do anything good for anybody if you don’t stay in business. So, as a starting point, you have to make sure you have good, solid business skills and can actually run a healthy business. If you can’t do that, nobody has jobs, you can’t help customers, you can’t do anything.

Ariyoshi: My view is, leadership is not a quality that’s inherited or given to you by the Almighty. Leadership, many times, is learned. The organization has the responsibility to try to train and develop that leadership skill. Nobody’s born with leadership experience. People like to say, “Oh, you need experience.” But somebody has to give those people the experience so they can develop the qualities that make it possible to become good leaders.

What you have to do is look for a person who’s bright, willing to learn, has a vision or can develop that vision. When I was governor, the core of the work in my office was done by five or six young people, some of whom were still at the university. They did a really good job. They went to the departments, but I told them, “You’re not going to go there and throw your weight around and say you’re from my office and tell them what to do. Go in there, find out what’s happening, find out what needs to be done in order for the government to function properly.” Some of those people are still leaders today.

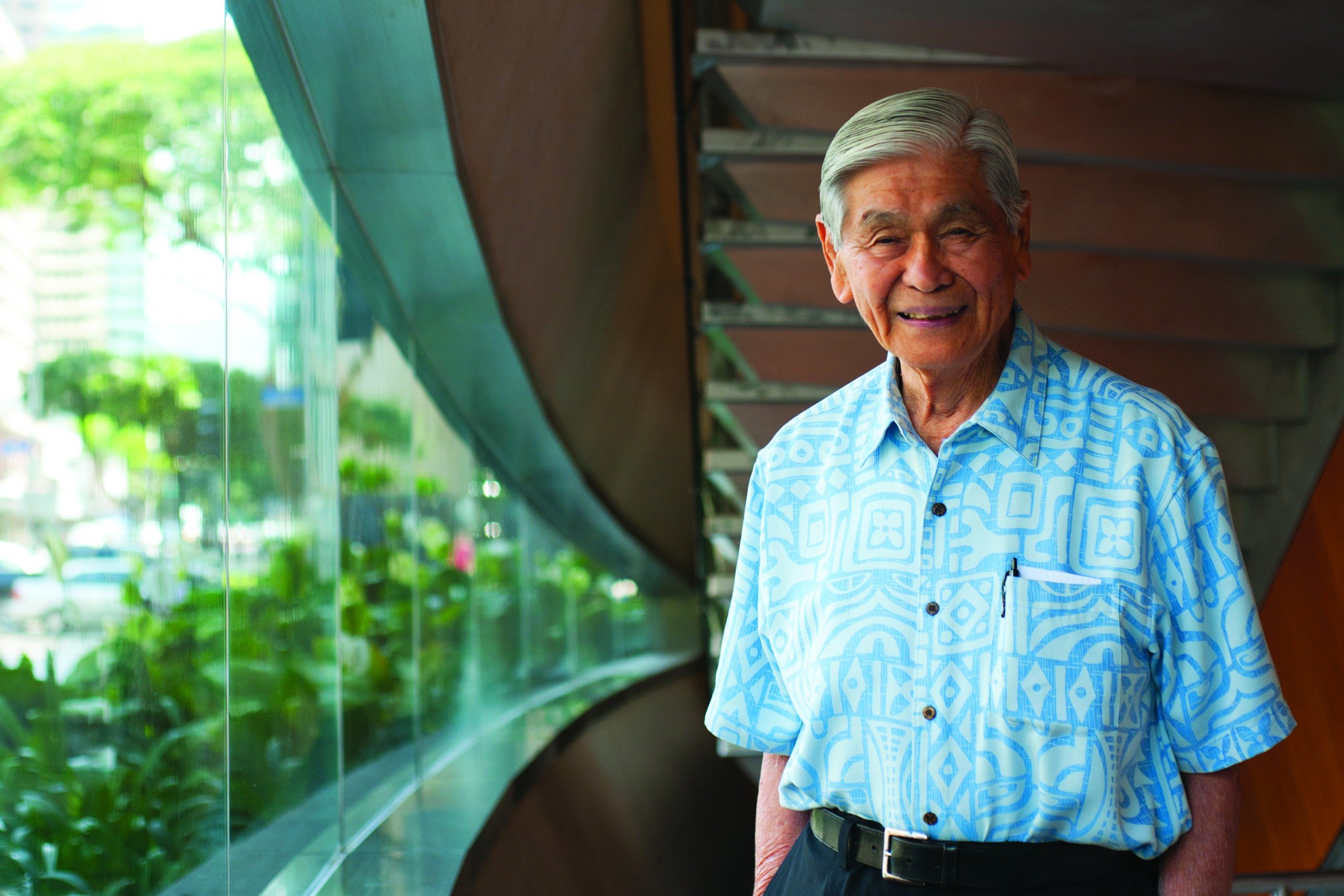

Former Governor George Ariyoshi in downtown Honolulu, Hawaii. Photo: Elyse Butler Mallams

How do you identify those young leaders?

Lau: The nice thing about life, starting from when you’re in school, is that you can usually tell which people are natural leaders. Even when they evaluate kids for admission to schools, even before they know their ABCs, they do things like observe them on a playground and how they interact with other children – whether they naturally attract other people. So, in a large corporation like HEI, you automatically see those people who naturally rise. My husband likes to use the old expression, “Cream rises.” Well, leaders appear.

You don’t necessarily know who is going to be the leader who makes it all the way to the top, but that’s what our talent-development and executive-development programs are about: taking and developing those who distinguish themselves. Early in their careers, it’s largely about individual effort; hard workers who want to make a difference in the workforce. They start appearing through them normal performance evaluation systems. Then, we take those who look like they have potential and we start to develop them. We gradually give them more responsibilities and broader responsibilities, expanding their experiences and the skills they must develop to deal with those experiences.

Dods: The best way to identify leaders, I agree, is to give them assignments outside of their normal responsibilities. Don’t identify them publicly; identify them in ways like providing cross-training opportunities. That’s the best training of all: Move them around so they learn both staff and line functions. And provide them with education and mentoring.

It can change. You don’t pick that person and it’s cast in stone. You might pick two or three people. But the one cardinal rule that I see companies break – and it always destroys them – is to pick (multiple heirs apparent). First Chicago Bank did that famously way back. At one time, a local company, Amfac, announced five heirs-apparent. It was a horrible thing to do. Each one formed cliques, and people were on one guy’s team or another guy’s team. What happens is, one person wins and the others either leave or become disgruntled.

Take a look at what happened with General Electric (when it had a very public competition among top leadership to succeed Jack Welch). All those top guys left. Some of them did well after they left, some didn’t. But it was all a loss to GE. If it had been handled differently, they could have saved some of those people. While they point GE out as the model of great leadership, personally, I think it destroyed a lot of shareholder value by losing a lot of key people. And the jury’s still out whether the one they picked was the best one, because some people who left have done better. (Alan) Mulally at Ford, for example. GE’s performance has been mixed.

How early can you start to identify these young leaders?

Lau: I loved being an operating officer, so my favorite job was running American Savings Bank. When I was there, I used to go to every single orientation. You ask how early do you want to start looking for talent: I attended the orientations because I wanted to know what talent was coming into the corporation. And after every orientation, I would make notes about who was particularly impressive and I would kind of track them or make a mental note to watch their careers to see if they distinguished themselves. So, it’s never too early. It’s like watching those kids on the playground: You can spot the natural leaders.

But you always try to develop everybody, because you never know who’s an early bloomer and who’s a late bloomer. You also never know what else might be going on in their lives. That’s particularly true of women, because women tend to have most of the burden of raising families. So, there are times in a woman’s life where she has to spend more time on family issues and can’t spend as much time on the job. But, when the kids are grown, that might be her time to bloom, from a career standpoint. Now that there’s more sharing among spouses, that can be true for the guys, too. We have some guys who’ve turned down promotions because of their choice to spend more time on the family side.

Connie Lau, CEO, Hawaii Electric Industries | Photo: Elyse Butler Mallams

How important are mentors during transitions?

Matsumoto: It’s important for leaders to have role models. You could have a role model based on a third-party relationship, someone you read about in a biography, for example. But, ideally, you want to have actually worked with people who have outstanding leadership skills so you can learn directly. If your models for leadership are just people in biographies or who you see in movies, there’s a tendency for them to be idealized. It’s important for people to recognize that great leaders are just like ordinary people in a lot of ways – probably more ways than not. It’s important for somebody who has the potential to become a leader to recognize that. They have to appreciate that fact to become outstanding leaders themselves.

When you have the opportunity to work with somebody who has good leadership skills and is a good mentor, you learn two things. You learn about how great the person is and how they have such outstanding qualities. But you also have the opportunity to learn about their faults and limitations. You realize they’re just human, but, in spite of that, they’re able to achieve great things. If you can see and appreciate that, then, as flawed as each of us are, you can still aspire to leadership and make a contribution.

Is there an adequate pool of young, potential leaders in Hawaii today?

Dunkerley: The distribution of gifted, smart people is every bit as high here as anywhere else in the world. So, I don’t think there’s any shortage of bright people. I think one of the challenges for Hawaii in general is that we’re in an increasingly global marketplace, and to be a leader in businesses that are increasingly global requires that people have experience of the world, have experience outside any one location. That’s not just for Hawaii; the same would be true, for example, in Washington, D.C, or any other place. So, we have many talented young people here in Hawaii. My ardent hope is that they continue to enter the workplace and have high aspirations for leadership. But it’s also my hope that they go out and see the world and see the kinds of societies and cultures that are inevitably going to shape our world here in Hawaii in the generations to come. And if they buy their tickets on Hawaiian Airlines, so much the better.

Matsumoto: One thing that frustrates me about the younger generation is their reluctance to step up into leadership roles. I think the current generation of young people – people in their 20s and 30s – are probably a lot brighter and more knowledgeable than my generation was. But I see a certain lack of willingness to lead change. That’s why, when I talk to a lot of young people, I say, “John Mayer sings the anthem of your generation when he sings about, ‘Waiting on the World to Change.’ ” The first time I heard that, I thought, “What’s with this song?” Yet, the more I think about it, the more I realize it’s characteristic of this younger generation. Maybe they’re just too comfortable. I’m a child of the ’60s. We had civil rights. We had the Vietnam War and the antidraft movement. We had the war on poverty. We had the beginnings of the environmental movement. Young people were the ones that led all of that and basically asserted themselves to bring about change in society. I don’t see that same fire with the younger generation.

Dunkerley: I don’t think that’s a problem, frankly. When you’re young and just starting out, you often don’t have much scope to exercise an interest in leadership. Certainly, when I started out, I didn’t say to myself, “One day, I’m going to be fortunate enough to be running an airline.” When I look back on myself, I can’t say, when I was in my 20s or 30s, I had a clear plan. I can hardly be critical of people in their 20s today who haven’t totally found out their track. I would also say the pressure is much greater on this generation than it was in my day. I’m always staggered by the quality of the resumes I look at compared to my own resume at the same point in my career. It’s not enough, these days, to have gone to a fantastic school and done well. It’s not enough to list your hobbies as “travel” and “reading history.” There’s an expectation that you’ve done something as a person to meaningfully contribute to your community. That’s a very different standard than the one we grew up with. I think we can all agree on that. It’s staggering. So, I think it’s unfair to talk about younger people today not being interested in leadership.

Matayoshi: I think this generation is different, even if you just look at employment patterns. The days when people stayed with one company, when the majority of people looked for long-term stability, are gone. More people are willing to change jobs. They’re not thinking they’re going to be somewhere for 20 or 30 years. There’s also a certain impatience about where they are and what they want to accomplish. For them, it’s a lot more about doing what they want to do than what other people tell them to do. So, for a leader, motivating them becomes a different experience.

Speaking of differences, is there a difference between leadership in normal times and in a crisis?

Ariyoshi: It depends on how you define crisis. Almost every day, you have problems. Every day somebody protests, somebody doesn’t like what’s going on. You’ll find that, when you put a policy in, it will be very good for some people in Kahala, but for the people in Waianae and Nanakuli, it may not be very good. That’s because the communities are so different – a difference in education, in jobs and the things that we need to do, a difference in our culture. So, every day, when you want to do something, you have to deal with this vast, diverse impact on people and find a way to make it possible.

Dods: Sometimes there can be a difference in normal leadership and in crisis leadership; sometimes they can be the same. The old example I like to use is the Mafia, with the wartime consigliore and the peacetime consigliore. Those were terms actually used by the Mafia. You might have a guy who was a great general/legal counsel during peaceful times, and then you had guys that were built for war. In the U.S. military, it’s the same way. I’m not sure you’d want George Patton to be your peacetime leader – in fact, I’m sure you wouldn’t – but, in time of war, he was one hell of a general. So, there are times when companies go through crises that you need a certain kind of leader. Today’s term for that would be a restructuring kind of leader. There are times when that kind of a leader is very good at slashing costs and canning a lot of people to save a company, but couldn’t grow a company if their lives depended on it. There are others who can do both, so it’s not always one or the other. But there are clearly people who are good at one skill, and not the other.

Matayoshi: The times matter. You need a little bit different kind of leader in a crisis. Part of it is being able see the opportunities that a crisis brings. I’m talking mostly about big, long-term things, but even one-time things like fires and natural disasters can suddenly change the paradigm within which an organization operates. It can be a catalyst for positive change, if you view it that way. It doesn’t make it any easier, but it’s a more positive way of looking at crises. That’s a different kind of person than one starting off with a blank slate, trying to build something.

Matsumoto: Crises are the best opportunity to test a person’s leadership. When a person is confronted by a crisis, the first quality I would want to see in that person is whether or not he has the ability to be calm under those circumstances. Because, if a leader cannot maintain calmness in a crisis, he or she cannot evaluate the situation properly and respond correctly. So, the ability to maintain your composure as things are collapsing around you is a key quality a leader needs to have to deal with a crisis.

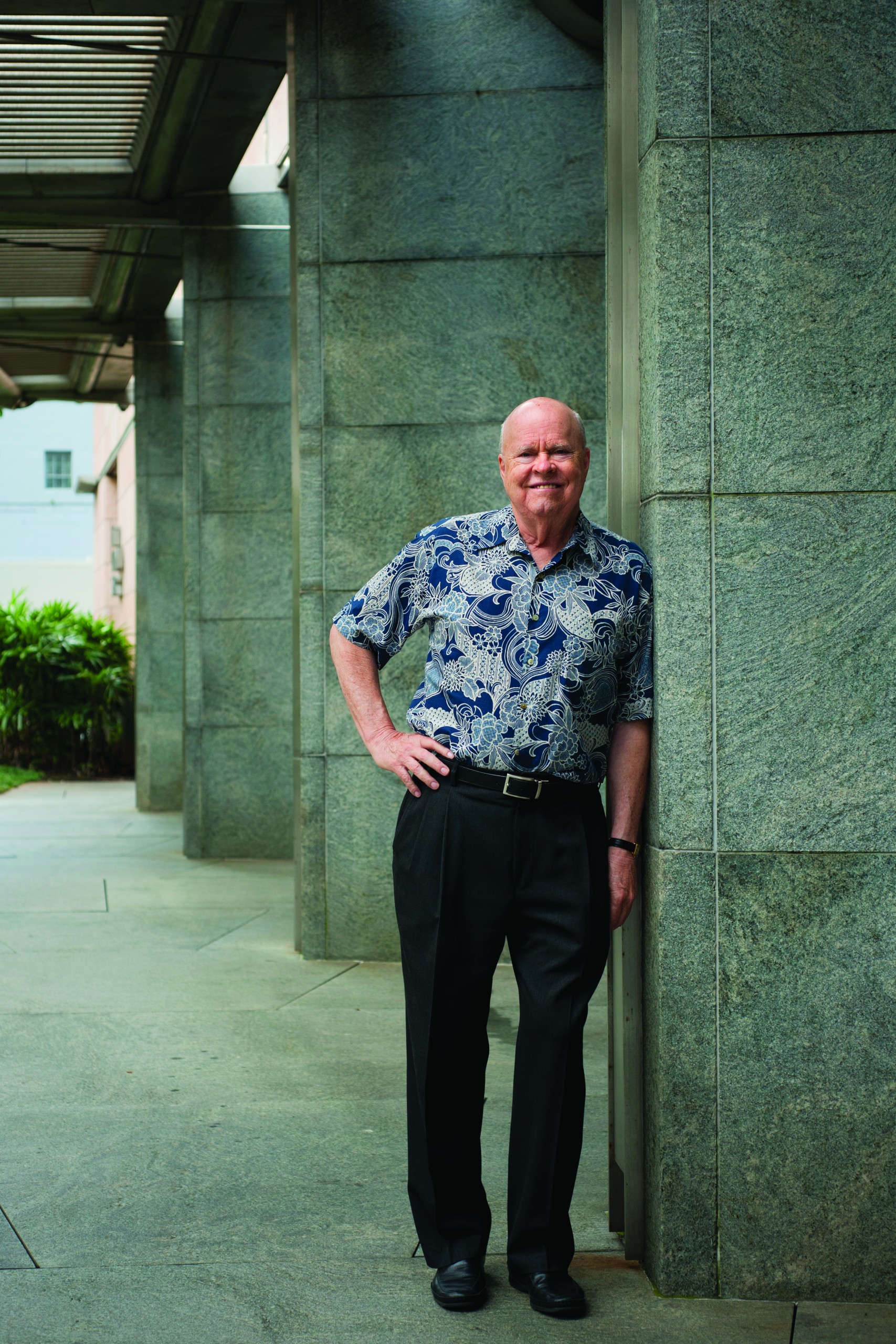

Walter Dods, one of the most influential men in Hawaii, in his office and around the First Hawaiian Bank building which he designed himself. Photo: Elyse Butler Mallams

But how does all this change the way you lead in a crisis?

Matayoshi: At DOE, a lot of it has been around the downturn in the economy. Oddly, that’s what I’ve always faced when I’ve been in government. So, there’s a strong element of being very strategic, very focused on the things that make the most difference. In a fiscal crisis, you don’t have the luxury of spreading resources to a range of things; you have to say some things are more important than others, or, at least, more strategic than others. That’s why strategic planning keeps being our focus. It’s allowed us to say, “These are the things that are important.”

Dean: In a crisis, you never have perfect information because you don’t have sufficient time. So, you have to be more authoritarian, and less collaborative, in a crisis. At least, that’s been my experience. I shouldn’t judge for others, but that’s my style, typically. That doesn’t mean you don’t treat people with respect – I think in both situations you do – but you don’t have the luxury of weeks or months to develop an idea and make a decision. So you make a lot of decisions, some of which you find were not the right ones, and it affects people, but you move quickly. At least, that how it’s been for me – not just here, but in the other banks in which I was involved in turnarounds.

Matayoshi: Many years ago, when I was at Hawaiian Electric Co., we had a group that was supposed to help define “Leadership in the 21st Century.” We asked Dan Williamson, who was CEO at the time, “What do you think is the most important attribute of a leader?” He said, “The ability to deal with ambiguity.” It was about making decisions without all the facts. He thought that was going to be one of the most important characteristics of leadership in rapidly changing times. And I always remember the ambiguity part. It always made a lot of sense to me. You don’t always know everything, and sometimes if you wait, it’s too late.

Dean: Then, the question becomes: “When you’re not in a crisis, what’s the approach?” My style – and I think people here will tell you this – is to empower people. To collaborate and empower and push decision-making down as far as you can within the organization. Because there’s more buy-in and ownership of those decisions when people get to participate in them. I think great organizations are built not on a dictatorial, command and-control model, but by pushing decision-making down into the organization. And that’s what we’ve done at CPB. Now, I would say that, in either situation, the crisis or the normal or good times, you still need what I call core values – how you treat people. Even in a crisis, you should try to treat people with respect.

Lau: I think the basic principles remain the same in a crisis; it’s just that you have to lead in a heightened atmosphere. What becomes really critical in a crisis is to be able to think clearly and act clearly. You have to process massive amounts of information in very little time, identify the root causes and triage the problem. You don’t have time for longer-term strategies. But, as soon as the crisis is over, you need to move to a longer-term approach to address whatever caused the problems.

In a crisis – and this is another important leadership trait – you must be able to look inside and find strength within. Because, very often in a crisis, everybody is in a panic and, lots of times, people are looking for someone to blame, and you have to know whether you really are at fault or not. If you lose that ability, you can’t lead.

Also, in a crisis, you have to be more action-oriented than in normal times. Consensus is a characteristic of managing in Hawaii. The workforce here expects leadership to be more inclusive and to really care about a lot more aspects to a problem than other places might. An easy example is that, in other places in the country, people might be more clearly financially oriented. For them, the bottom line translates into financial success. Whereas, in Hawaii, we talk much more about double- or triple- or even quadruple-bottom lines that also value culture, our cherished aloha spirit and the environment. We, as the people of Hawaii, tend to value things more broadly. We’re not so strongly financially oriented; we also care about quality of life, balance of life and preserving what’s special about Hawaii.

When you ask, “What happens to all of those values in times of crisis?” I think you still try to do the same thing, which is sort through all the different values, but you have to do it much more quickly, and you probably can’t do it with as much input. But you still need to try to solicit as much input as you can. I was talking earlier about positional power. Well, you need to know when to exercise that positional power, and when not to. I think you want to try to not exercise it as much as possible, and rely mostly on building consensus and accommodating as many views as possible – allowing a group to lead itself, with the right guidance. But, in times of stress, you need to exercise the authority you have. Those are not easy judgment calls: when to hold back, and when to exercise authority. That’s the skill of leadership.

I must say, running a large corporation, especially in the format we’re in – a holding company, where I have very capable CEOs at the operating companies – you want to allow people to make their greatest contributions. If I’m always mandating what should be done, I’m not going to be able to gain the benefit of their creativity, views, vision and abilities. It’s a funny thing: Leading is really an art. It’s definitely not a science. And it differs depending on the circumstances. I always say leaders have very wide skill sets, which they can bring to bear in the appropriate combinations for particular situations.

Dunkerley: When I was at a previous company, at one point we did one of these temperament assessments, like a Myers-Briggs test. I remember one detail of the test was that it divided people into categories like “fundamentally emotional” or “fundamentally analytical,” etc. The assessors made the point that, wherever people start in that spectrum of attributes, they tend to become more like themselves under pressure. So, whatever sort of innate biases they have, they tend to go to the extremes of that spectrum under pressure. That sounds highfalutin, but, frankly, we all know that. We know, from the people we’re close to, that, if they’re under a bit of stress, they tend to exhibit more prominently the characteristics they have sort of inherent in them.

So, the best crisis management really is about people who are relatively balanced between the emotional and the analytical, the here and now and the long term. Because, if you’re not relatively well balanced and in the middle, as the stress builds, you’re likely to go increasingly towards the corners of the two biases. So, you’ve got some very good leaders for sunny days who aren’t as good for rainy days.

CEO John Dean of Central Pacific Bank at his office and in downtown Honolulu, Hawaii. Photo: Elyse Butler Mallams

Who are the leaders you most admire?

Ariyoshi: I think Jack Burns very clearly was a great leader, because Jack Burns felt we should have more people involved in the affairs of the community who were not then involved and didn’t feel they had a right to be involved. For me, Jack Burns was a great person. Right after I was elected as lieutenant governor, he told me, “I’m Caucasian, you’re Japanese. I didn’t go to school here, you went to school here. Your culture is very different from my culture. So, I expect, from time to time, you and I are going to have differences of opinion.” But, he said, “That’s OK. I don’t want you to feel you have to agree with me all the time.” And he told me, “You’ve got to be true to yourself. You’ve got to be your own man, and that’s fine with me as we work together.”

Sometimes, I think, a leader is not only what he or she does. Being a leader is a mindset – caring why things are done a certain way, a willingness to have some somebody else have a difference of opinion and be able to work together. From that point of view, Jack Burns had vision.

Dean: There are CEOs I admire, but my path has been more of observing many. I think a great CEO in the community here is Walter Dods, in terms of what he accomplished as CEO of First Hawaiian. But, people ask me, “Who’s your mentor?” Well, I had a confidante, my wife. And I had lots of bosses that I admired, and I tried to emulate what I think are their best qualities. But I think I’ve learned as much from bad bosses as from good, in terms of what not to do. Whenever I was treated a certain way or thought something was unfair, rather than be angry, I tried to remember and promise myself I would never do that when I was in that situation – from little things to big things.

Matsumoto: Who do I consider to be visionary leaders in our community? I’ll give you three names: I think Nainoa Thompson is truly a visionary leader. Anybody who’s had the privilege of hearing him speak about voyaging and the role of the voyaging canoe within the Hawaiian community and in greater Polynesia, can’t help but be inspired by the vision he has about the role the canoe is supposed to play in transforming society. I consider him to be somebody who has the ability to see the big picture, and who is willing to try to bring about change on a global basis.

Another person I think about is Pono Shim, the CEO of Enterprise Hawaii. What I appreciate about Pono is his nonlinear approach to economic development. His approach is culturally based, and I think the question is: “How do we transform Hawaii in a way that enables our society to prosper, yet maintain the cultural uniqueness about this place?” Pono is able to articulate this in a very unique and positive way.

The third person is Duane Kurisu. Duane has a bigger picture perspective of how he wants to bring about change within Hawaii. Maybe it’s not so much about change, but how he wants to promote some of the special qualities we have in Hawaii. But he won’t let you write that. Duane has a different perspective about how he wants to do business – how he actually does business and the investments he’s made. He’s another one who has audacious ideas that are sometimes a little crazy. (Disclosure: among other ventures, Kurisu is the owner of Pacific Basin Communications, the parent company of Hawaii Business.)

I’ve always appreciated that about really outstanding leaders. More times than not, they’ll really have a perspective that forces you to think, “Is he serious?” You get baffled by their ideas because they’re so different from what traditional thinking might suggest. It takes somebody special to see that vision and to be willing to associate themselves with it, to articulate it and promote it so that other people might embrace it. You run the risk of people saying, “Did you listen to that guy? What a flake! He’s crazy.”

Are there aspects of leadership at this level that most people don’t think about?

Dean: It can be lonely at the top. It’s important to have a confidante. Because it’s hard, when you’re at the tip of the pyramid, to confide in someone. You don’t have peers, so what do you do? For me, it was my spouse. Some people have mentors. In some companies, the CEO gets a coach. Sometimes, it’s a good friend in the business community, but not related to your business. Sometimes, it’s just to vent, just to have someone to listen to you.

Dods: That’s the toughest part when you get into these really high-level jobs. I’ve talked about balancing community and job, but there’s a third factor, and that’s family. When you add up that equation, it really gets tough for those who really want to go all the way. And, to be blunt, one or the other is going to suffer in some form or another. It’s very hard to balance all three of those things. The secret is to understand that and to try to manage that process. But it’s not easy.

Matsumoto: I used to have a close mentor who was fond of saying, “Show me a leader who has no enemies and I’ll show you somebody who hasn’t accomplished much.” I think it’s really hard to demonstrate true leadership and still make everybody happy, because you have to make choices, and not everybody will agree with those choices or gain the same benefit from the choices that are made.

So, it’s inevitable that some people are disgruntled with the decisions a leader makes. That’s especially so now, in our current age, when people are much better educated, much better informed, and everybody has an opinion and they’re not hesitant about expressing it. The fact that people do form strong personal opinions about things makes it more challenging to get larger groups of people to align behind anything. It’s much harder to build consensus than it was, say, 50 years ago.

Maybe because of that, I also think leaders today have to be much more sensitive and skillful with respect to public relations. They need to have better insights into what people are interested in or concerned about, how to motivate people through public messaging. Even if your cause is virtuous, if you don’t have the ability to communicate in a way that will persuade people to align behind you, you won’t be successful.

Dunkerley: A couple of years ago, I had lunch with another leader here in this community, from a very different walk of life, and we were musing about the twists and turns that our lives had taken, and about why we, in our respective fields, had been successful. Why us? Why had we passed by other people, much more talented and able than ourselves, to rise to the top? The big thing we both considered was remarkable was how many people undermined their own abilities by being unable to see beyond themselves. You see that constantly.

I’ll give you an example: In the senior management team, as you would expect, we have to deal with some really hard issues, budget issues – does that marginal dollar go into so-and-so’s department or any of a myriad different things. As a team, we have to make those decisions. One of the most limiting things a person can do in that environment is fight for his or her own corner to the disregard of the company as a whole. It’s an affirmative plus mark when somebody says, “I would like those resources, but, looking at it from the company’s perspective, I think John or whoever could use them more effectively than we could right now.” It’s surprising how difficult it is for people to do that.

This is hard for the CEO to say, because our paychecks are the biggest, but a selflessness of approach is enormously important – a willingness to not see things in one’s own context. The example I would offer you is our new open-office environment. When we renovated the offices, it would have been very easy, perhaps even expected, that the nicest office would go to me, and the group of the nicest corner offices would go to senior officers. But there’s tremendous power in saying that the people we need to look after are the people at the bottom of the organization whose work environment would be diminished by the big bosses taking for themselves.

The classic example here is: We only allow food to be consumed down in the new company cafeteria. So, we all eat together at family-style tables. We want to encourage employees to be part of our ohana. It would be the easiest thing in the world for me to break these rules. I have extremely busy days when it’s deeply inconvenient for me to go down there to swallow a sandwich in three bites. But, if I were, just once, to give myself that latitude, then I’d be setting an example that, on balance, would undermine my leadership.

Another thing about leadership is that, out of 100 decisions, it’s not how you make the 99 easy ones that people look at to find out who you are; it’s how you make the one difficult decision. I’ve been in situations where there were people in leadership positions who fundamentally didn’t understand that. They didn’t understand why, when they were, in everyday interactions, making decisions left, right and center that nobody disagreed with and everyone was basically happy with, and they still ended up being unpopular. The reason was because of the way they behaved when the chips were down. People are smart. They spend their whole lives making assessments of other people, and they’re very shrewd. They will see right through somebody who, when the sun is shining, is easy to work with, easy to get along with, but who turns out to be very different when times are hard.

Matayoshi: One thing, at least for me, is that a lot of people don’t realize how many sides a story can have. When a decision is made – especially if it’s wrong – it’s hard for them to see the other side of it. But, as a leader, you can’t make those decisions without considering all those perspectives, short term and long term. It’s hard to explain that without sounding like you’re making an excuse: “Oh, there’s another perspective that you haven’t seen.” But, every hard decision usually has another side, or multiple sides, and balancing all those perspectives to try to reach the best decision sometimes isn’t easy to explain. I like to ask myself, “Are you doing the right thing?” You might be wrong, but are you trying to do the right thing with the best information you have?

Lau: If you are given positions of leadership, you gain what’s called “positional power.” But it’s really important to treat that power with great respect, and to use it as a last resort. I always remember Admiral (Robert) Kihune when I was at Kamehameha. When the interim trustees were put in to clean up all the mess, the other four trustees were all very distinguished, recognized leaders, and I was sort of the young kid on the block, so I always call it my “lessons in leadership.” Admiral Kihune was a Kamehameha graduate who was the first Native Hawaiian to become a three-star admiral. He was the one who was chosen by the Navy to clean up after the Tailhook scandal. Francis Keala had been chief of the Honolulu Police Department. During his time, the department was accused of graft and corruption, and Chief Keala was the one who cleaned that up.

One night, after a very long community meeting, where I’m sure we resolved nothing, but we certainly heard many, many perspectives, I pulled Admiral Kihune aside and said, “Admiral, I’m not sure I understand this. You were an admiral in the U.S. Navy, and I thought that, in the military, you all have a saying that, ‘When in command, take charge.’ You’re our chairman of the board, and I’m surprised you’re not taking a stronger hand in these community meetings and taking charge.” And he said to me, “Connie, those kinds of ringing phrases work in wartime. But, in times of peace, it’s very important for leadership to listen to the people, because we only hold leadership because of those who will follow us. So, you need to know what the people think.” It’s not about any of us as leaders; it’s really about where do the people want to be led. You never know that unless you open yourself up and listen. That fit into my own vision of leadership, which is servant leadership.

What advice would you give to up-and-coming leaders?

Dods: I would advise people reading this article to seek out the lousy project, the pesky project, the project that nobody in their organization wants to touch, one that people know is going to be hard, and volunteer for it. A critical part of this leadership question that I’ve analyzed over the years is: How do you, as middle management, break out of the box and become someone that senior management becomes interested in? That’s the most critical thing. Let’s say you have seven people of equal educational background and more or less comparable job experience. One or two of them always break out of the pack. You’re not going to need seven CEOs in that company, but you may need a chief operating officer and a CEO.

How do they break out of that pack? Management has the responsibility to observe and judge them, look at their reviews, etc. But they have the responsibility also to get noticed. Now, that sounds to some people almost offensive. But they’ve got to figure out how to break out of the pack. The way you do that is: A, you do your job better than everybody else. But also you try to find and seek out opportunities to do jobs that may not necessarily fall into your job description.

Ariyoshi: Don’t do things because you want credit. Do things because you believe they’re the right things to do, that they will be best for the organization for which you work. Be unafraid to do things that have never been done, or in ways that they’ve never been done before. But think a lot before you do it. It should not be something whimsical – “Oh, I want to do this!” – you’ve got to think it through; then try to make it work. Too often, we’re stuck with traditions, with what was here before, with what someone did before. I think an up-and-coming leader must not be so bound. The courage to do what is right is very important. And, as I mentioned before, don’t do it because you want credit. That’s a big fault. People think, “If I do this, I’ll look good.” They should think, “If I do this, things will be better here.” The project will be better. The company’s security will be better. And it may make somebody else look good.

You also can’t be a know-it-all. You’ve got to be a person who’s willing to admit that you don’t have all the answers, that the vision you have, the things you want to do, might need some modifications because of the impacts they have. That’s the other thing about what people said when I had my state plan. They were saying, “Oh, what’s the plan for? You can’t predict the future. You don’t know what things will change.” My response was, “That’s the dynamism of planning.” You set yourself up for whatever you want to do 25 or 35 years ahead, but, as you get there, you find out certain things along the way and make certain adjustments as you move ahead. But you know where you want to end up. That’s the dynamism of planning, because when you plan, you know where you want to go, but you also know you may have to make some adjustments along the way to get there. Nobody’s smart enough to say, “Hawaii, 30 years from now, is going to look like this, and I’m going to plan it exactly, with all the details, so we get there.” It’s not possible. That’s why a good leader has to be willing to acknowledge imperfection.

Dods: In my mind, a real leader is somebody who has to come up two tracks: within the company and within the community. Anybody who thinks you can be successful just doing your company’s business is wrong, because every company derives its income from the community in one way or another. And the true leaders, in my opinion – the ones I look for to promote, advance, mentor – are those who understand you’ve got to do both things. You’ve got to come up the community leadership ranks, and the company ranks.

And, if you do community for the right reasons – meaning, that things need to be done – you also get the side benefits of learning leadership at a harder level, because it’s much harder to motivate volunteers. You don’t have power over them. You can’t say, if you don’t do your job, you won’t get a raise or I’m not going to keep you employed. When you do community, you’ve got to motivate people based on your leadership, values and salesmanship. And, over time, those are qualities that will serve you tremendously within the company as well.

Another thing I always tell people is, “Be local, Brah.” I feel very strongly about that. I don’t mean you actually have to be local – not at all. You can come from anyplace or culture, but you need to learn to respect the local culture if you want to be a successful leader. Some people come to Hawaii and within a week they’re local. Some people are here forever and they’re never local because they don’t understand and respect our culture. I’ve seen a hundred people – and I’m not exaggerating – come here and say, “We’re going to change things because this isn’t how we did things in Boston or New York.” I’ve seen them come and I’ve seen them go. I remember magazines like yours running major stories about how we’re going to get buried because someone like Bank of America was coming to run an S&L or whatever, and they were gone three years later. I’ve seen it my whole career.

So, what I mean by local is clearly understanding and respecting local culture. If you put that together with values, community service, communication skills, strategic vision, then you’ve got an easy leader.

Matayoshi: It’s funny, I was telling some of the guys at work, “You should read the papers. You should keep up with the news on things like what’s up with tourism.” And somebody said, “Well …” And I said, “No, tourism is one of the largest drivers of our economy. It impacts the state’s general-excise-tax collections, and DOE gets 25 percent of that. So, when there’s something that disrupts airline flights to Honolulu and you lose seats from Japan or otherwise, it makes a difference to the economy, so it makes a difference to the budget and it’s going to make a difference for us.”

I think part of being the leader is to really have an understanding that you’re not an isolated organization. Part of being a leader is to look externally and be thinking about the challenges and problems that might be coming along. You don’t always have to take action on every single thing, but you’re always aware of the environment in which you operate. Also, you always want to be aware of opportunities to partner with others – especially in the public sector – around a common goal.

Dunkerley: I’m a huge believer in the diversification of the workplace. I say that not out of any particular desire to be politically correct, but, in a business like ours, you have such a broad spectrum of activity, and therefore a broad spectrum of challenges, it seems self-evident to me that, in the leadership team, you need a broad spectrum of people. You need people who are of this community and know absolutely everything there is to know about it. You need people who know the airline industry inside out, because they’ve been at many different airlines. You need men as well as women, because men and women process information differently. They make decisions differently. They can see the same set of facts in slightly different ways, and if you don’t have that represented in your internal councils, you’re blinding yourself to the situation. You need different generations because, as you move through life, the way in which you think about things actually changes, which is important. The situation I want to avoid is when you look at the leadership team and everybody looks like a mini-me of the leader, as opposed to the broad spectrum of all these attributes.

Dods: I like the old saying: “Don’t be a slave to conventional wisdom. It may be conventional, but it isn’t always wisdom.” Real leaders are the ones who are willing to think outside the box. Again, that’s a trite saying, but it’s really true. Taking people to a different level requires not doing what everyone else is doing.

Mark Dunkerley, CEO and President of Hawaiian Airlines at their corporate office in Honolulu. Photo: Elyse Butler Mallams

Seven Leaders

George Ariyoshi

Former three-term governor of Hawaii, former board member of First Hawaiian Bank and Hawaii Gas Co., former chair of the East-West Center board of governors.

John Dean

President and CEO of Central Pacific Financial (parent company of Central Pacific Bank); turn-around specialist who also led the revival of three mainland banks; UH regent; 2012 Hawaii Business CEO of the Year.

Walter Dods

Chairman of Matson; former CEO and chairman of First Hawaiian Bank; former chairman of Alexander & Baldwin and numerous nonprofits; mentor to many CEOs and other leaders in Hawaii.

Mark Dunkerley

President and CEO of Hawaiian Airlines; former COO of Sabena Airlines and Worldwide Flight Services; 2010 Hawaii Business CEO of the Year.

Constance Lau

President and CEO of Hawaiian Electric Industries, former president and CEO of American Savings Bank; former chairwoman of Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate.

Kathryn Matayoshi

Hawaii public schools superintendent; former director of the state Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs; former executive director of the Hawaii Business Roundtable.

Colbert Matsumoto

CEO and chairman of Island Insurance, board member of numerous nonprofits, trustee of the state Employee Retirement System; former court-appointed master of Kamehameha Schools/Bishop Estate.

Hawaii Business Leadership Conference – Coming in 2015

Training, tools and networking that will enhance your leadership abilities and take you to the next level. Special programs for young professionals and emerging leaders. See below for information on last year’s event and visit the HB Signature Events page to view pictures in the gallery.

Keynote speaker:

- Dusty Baker, both an outstanding player and manager in Major League Baseball. Was part of the Los Angeles Dodgers when they won the World Series in 1981 and later was manager for the San Francisco Giants, Chicago Cubs and Cincinnati Reds for a total of 20 years.