How to Fix the Honolulu Zoo

If you grew up in Hawaii, chances are you’ve seen these exotic animals during a family visit or class field trip. And, if you’ve come back as an adult, a visit to Hawaii’s only zoo might have felt strangely similar to your earlier visits. Fluctuating funding and unstable management have hindered progress, making the zoo feel frozen in time, even partly shuttered. Some exhibits, like the hippo and reptile enclosures, have been closed for more than two years.

At the Honolulu Zoo, Asian elepants Mari and Vaigai are among the biggest and most reliable attractions. As the sign below left indicates, some other exhibits are not as reliable. Peacocks, such as the one shown at right center, are not penned in like other animals, but allowed to wander the grounds. The giraffe exhibit, bottom right, is another popular attraction.

It came as no surprise in March 2016, when the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, a national nonprofit that certifies 200-plus zoos and aquariums, stripped the Honolulu Zoo of its accreditation. The association’s reasons were well known – it warned the zoo in 2011 when it postponed accreditation for one year – the zoo lacked consistent funding, director stability and proper organizational governance.

Sweeping as these issues are, the iconic institution can be saved, and in time for when the city says it plans to apply for re-accreditation in 2018. In fact, voters have already stepped up to financially support the zoo when they approved a Honolulu City charter amendment in the November election. Next: Restructure the zoo organizationally and hire a dedicated, long-term director.

1 SECURE DEDICATED FUNDING

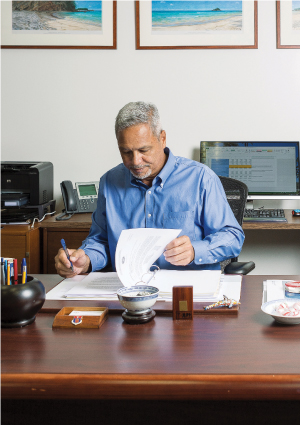

“The Zoo has never not been funded…but (the Association) would prefer that the Zoo’s funding was not subject to political cycles.” – Guy Kaulukukui, Director of the city Department of Enterprise Services, which oversees the zoo.

One of the biggest victories in the zoo’s century-long history came in November. About 57 percent of voters approved a Honolulu City and County charter amendment allocating 0.5 percent of property tax revenues to the zoo. That’s about $6.5 million annually, just under the zoo’s current budget. One of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ three critiques in denying accreditation against the Honolulu Zoo has been solved.

Guy Kaulukukui, the director of the city Department of Enterprise Services, says the city charter amendment was proposed as a direct response to the loss of accreditation. “The zoo has never not been funded … but (the association) would prefer that the zoo’s funding was not subject to political cycles,” he says.

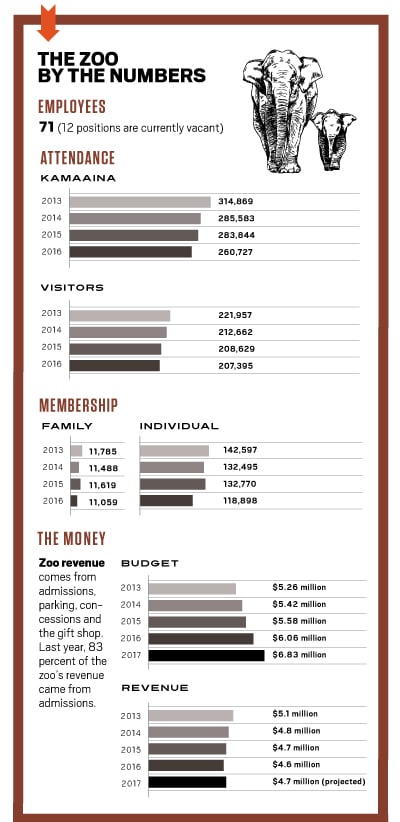

The Department of Enterprise Services oversees the Neal S. Blaisdell Center, Waikiki Shell, city and county golf courses and, since 1997, the zoo. Kaulukukui, who took office in spring 2015, says the zoo’s operating expenses this year total $6.8 million and its projected revenue $4.7 million. But the zoo needs about $13 million annually to cover everything, including $3.2 million in debt service. Since Mayor Kirk Caldwell took office in 2013, funding for the zoo has actually increased each fiscal year. But until the dedicated property tax, the zoo’s budget was subject to approval by the mayor’s office and the City Council, an amount that could easily change with a new administration.

Special funds or taxes for zoos aren’t revolutionary. Voter-passed initiatives for zoos exist in several cities, most notably for the San Diego Zoo, the Saint Louis Zoo in Missouri and the Albuquerque BioPark in New Mexico. (That’s where former Honolulu Zoo director Baird Fleming now works.)

“Funding and revenue are always the challenge. Cultural organizations in general struggle with these things,” says Rick Biddle, a consultant with Philadelphia-based firm Schultz & Williams. Biddle, who has worked with about 100 accredited zoos and aquariums, was brought in by the Honolulu Zoo Society to help the zoo restructure its business model in the wake of its accreditation loss. Biddle met with zoo stakeholders, including the Honolulu Zoo Working Group, formed by City Council member Trevor Ozawa, whose district includes the zoo.

Since 2013, both the zoo’s attendance and revenue have decreased, by a yearly average of 24,000 and $200,000, respectively. It makes sense, given that 83 percent of the zoo’s revenue comes from admissions. (As of press time, the city proposed raising nonresident adult admission by $2, to $16.)

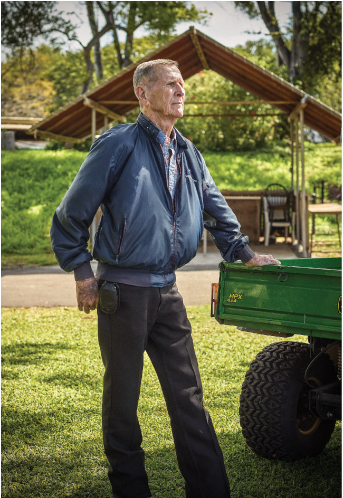

Trevor Ozawa says he’s made the Honolulu Zoo a top priority and even toured Mainland zoos to help bring best practices to the Kapiolani Park institution. “A lot of people I’ve spoken to (here) have indicated they feel that the Honolulu Zoo is not continuing to improve year in and out. It’s remained status quo,” he says. “While there’s some nostalgia with that, and some people like that, we need to keep up with times, we need to improve.”

The Zoo Working Group and Biddle came to the same conclusion: Even with stable funding from the real property tax allocation, the zoo needs to diversify its revenue to create better visitor experiences. The group’s suggestions include improved food facilities, behind-the-scenes animal experiences, increased educational programs, even an evening luau. “I already have a zoo in Philadelphia,” says Biddle. “When I go to the Honolulu Zoo it must be because there’s something different, something unique. What is that? We’d like to think that it’s always the animals, but it could just be a cool event.”

David Earles, the new executive director of the Honolulu Zoo Society, the zoo’s fundraising nonprofit, says he has a lot of ideas to bring in more local and tourists visitors, such as rebooting the zoo’s Twilight Tours. The society brings around $1 million annually through its fundraisers, donations and zoo memberships, he says. But only 35 percent of zoo membership fees – $200,000 to $400,000 in recent years – goes directly to the zoo; the rest funds society staff salaries, conservation and education programs and facilities improvements, like the new playground dedicated last fall.

Earles also thinks the zoo could boost attendance if it advertised itself. “When you start looking at the surveys and see how few people who walk the streets of Waikiki everyday realize there’s a zoo on the corner, that’s a painful thing for me to see. We’ve got to find a way to let people know we exist. We should be able to triple attendance at any given time just with awareness.”

2 RESTRUCTURE MANAGEMENT

“The relationships are pretty solid right now. We really do work well together.” -David Earles, Executive director of the Honolulu Zoo Society.

When the Honolulu Zoo lost its accreditation in March, the city went into overdrive to get the City Charter amendment on the ballot. But stable, and creative, revenue streams weren’t the only things that needed improvement. The zoo’s governance has long been an issue.

The zoo has its roots as a city-owned organization, ever since parks and recreation administrator Ben Hollinger began collecting birds and animals for exhibition in the city-owned Kapiolani Park in 1915. The zoo has since shuffled among city departments, but its staff, while responsible for animal welfare, are city employees and thus subject to policies set by the city Department of Enterprise Services. Then there’s the zoo society. Formed in 1969, the nonprofit is the fundraising arm of the zoo. In recent years, through a cooperative agreement with the city, the society has taken on conservation and education programs, something zoo staff used to conduct. It’s easy to see why there’s conflict.

“There’s sort of a natural tension there,” says Kaulukukui. “That’s where we are right now: needing to make sure our roles are clear.”

The complex management system for the zoo often has its three branches diametrically opposed. “The mission of the Department of Enterprise Services is to generate revenue for the city,” says former zoo director Baird Fleming. But the mission of the zoo, he adds, is to provide educational experiences about the organization’s ongoing animal conservation. “There’s a disconnect.”

That disconnect led Fleming to resign last November. “I felt like I wasn’t being listened to,” he says. “The loss of accreditation was a call to action from everybody, but a lot of that action did not involve consulting the zoo. That’s where things got bumpy. If you’re going to make changes for the zoo, you should involve the zoo.”

He says that, while the three branches all want what’s best for the zoo and even have similar goals – reaccreditation, more educational programs and better visitor experiences – the plans to achieve those objectives took different directions and communication broke down. Fleming’s departure after less than two years on the job illustrates the sometimes dysfunctional relationship between the city, the zoo and the society. And this wasn’t the first time. Bad blood among the zoo leadership has played out in local media for years with a rotating cast of city administrators, zoo directors and society executives.

Fleming notes that, while he quit, relationships were indeed improving. “It has gotten much better,” he says, “but it’s not fixed.”

Ask the city and the society and it’s a different story today. “The relationships are pretty solid right now,” says Earles. “We really do work well together.”

“For me, it’s always been good,” adds Kaulukukui. “I’m told it’s the best it’s been in a long time.”

Trevor Ozawa has made the Honolulu Zoo a top priority for his City Council district and has toured mainland zoos to learn best practices.

While Fleming no longer has a stake in the Honolulu Zoo – he’s settling in to his new position at the Albuquerque BioPark – he says the solution doesn’t need to be drastic: Give the zoo director more authority over the zoo, its staff and its programs. Fleming says this is the Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ standard. “They have found that when other governing entities try to step in and manage animal and staff concerns, things tend to fall apart.”

Biddle also suggests the zoo would benefit from more clearly defined roles, especially for the zoo director. “It doesn’t matter who did what, when,” he says. “Once you have a dialogue, then articulate it, here are their roles and then put them down in writing and make sure everybody understands how it will work.”

The opportunity could come as early as this summer, when the city hopes to have a new director in place. The city and the Honolulu Zoo Society are also negotiating a new cooperative agreement and plan to have it in place when the fiscal year starts in July. Currently, the two are operating on a one-renewal of their lapsed five-year agreement, says Earles. The agreement lays out the responsibilities of each – such as who runs the zoo’s education programs – as well as donation requirements to the zoo.

3 HIRE A LONG-TERM ZOO DIRECTOR

Interim zoo director Bill Balfour says he’s just “warming the seat” until a permanent director is hired.

A lot will be expected of the next director of the Honolulu Zoo. Namely, that she or he doesn’t quit after a year or two. The position has a bad record: In six years, there have been five directors. Fleming was director for nearly two years before leaving, but, before he took over, the previous two directors didn’t make it past one year. Organizational mismanagement got in the way for Fleming, but, he says, if the city, zoo and society can restructure their roles, the city can attract a well-qualified candidate who will want to stay.

Before the city launches its statewide search for a new director, Kaulukukui says, the department wants to reevaluate the zoo director’s job description to attract a long-term candidate. “How we tease that out is going to be more of an art than a science, but we need to find some way to evaluate that,” he says. He says the city expects to fill the position by June.

The pros for a zoo director job seeker? Thanks to the real property tax allocation, she or he doesn’t have to worry about the zoo’s budget. The animals are in good shape, even if the general animal population skews older. The zoo director’s salary is nationally competitive: Fleming made about $165,000. The cons? Governing relationships that still need improving, and a history that is not encouraging. Perhaps the biggest negative is the fact that the Honolulu Zoo is not accredited.

While the city looks for a new director, interim director Bill Balfour says he’s in no rush. “I’m just warming the seat,” he says. “I’ll stay until the position is filled.” The 85-year-old was originally brought on as a special projects manager in 2015 when the zoo was trying to catch up on deferred maintenance during its reaccreditation application process, so he’s familiar with zoo operations. Balfour says that while the city searches for his permanent replacement, he’s instituted weekly meetings with Kaulukukui, and is working to boost staff morale.

While the city looks for a new director, interim director Bill Balfour says he’s in no rush. “I’m just warming the seat,” he says. “I’ll stay until the position is filled.” The 85-year-old was originally brought on as a special projects manager in 2015 when the zoo was trying to catch up on deferred maintenance during its reaccreditation application process, so he’s familiar with zoo operations. Balfour says that while the city searches for his permanent replacement, he’s instituted weekly meetings with Kaulukukui, and is working to boost staff morale.

“We’ve got wonderful people here; they’re easy to work with,” he says. “When I run into them, I tell them things are going to get better. I think they’re still a little bit apprehensive, and legitimately so.”

That’s why Earles says it’s important for the city to take its time in finding the right person. “This position is too important and, because it holds the whole key to accreditation, (the city should) make sure it locks in someone who can take us back to accreditation.”

The Honolulu Zoo has checked off one of its three to-do items to get reaccredited and become a place vistors and kamaaina are excited to visit. By next reorganizing management roles and a hiring a long-term new director, the zoo can focus on why people go there in the first place: To see animals like Mari and Vaigai.