How the Hawaii Tourism Authority Markets Paradise to the World

Tokyo, Japan —

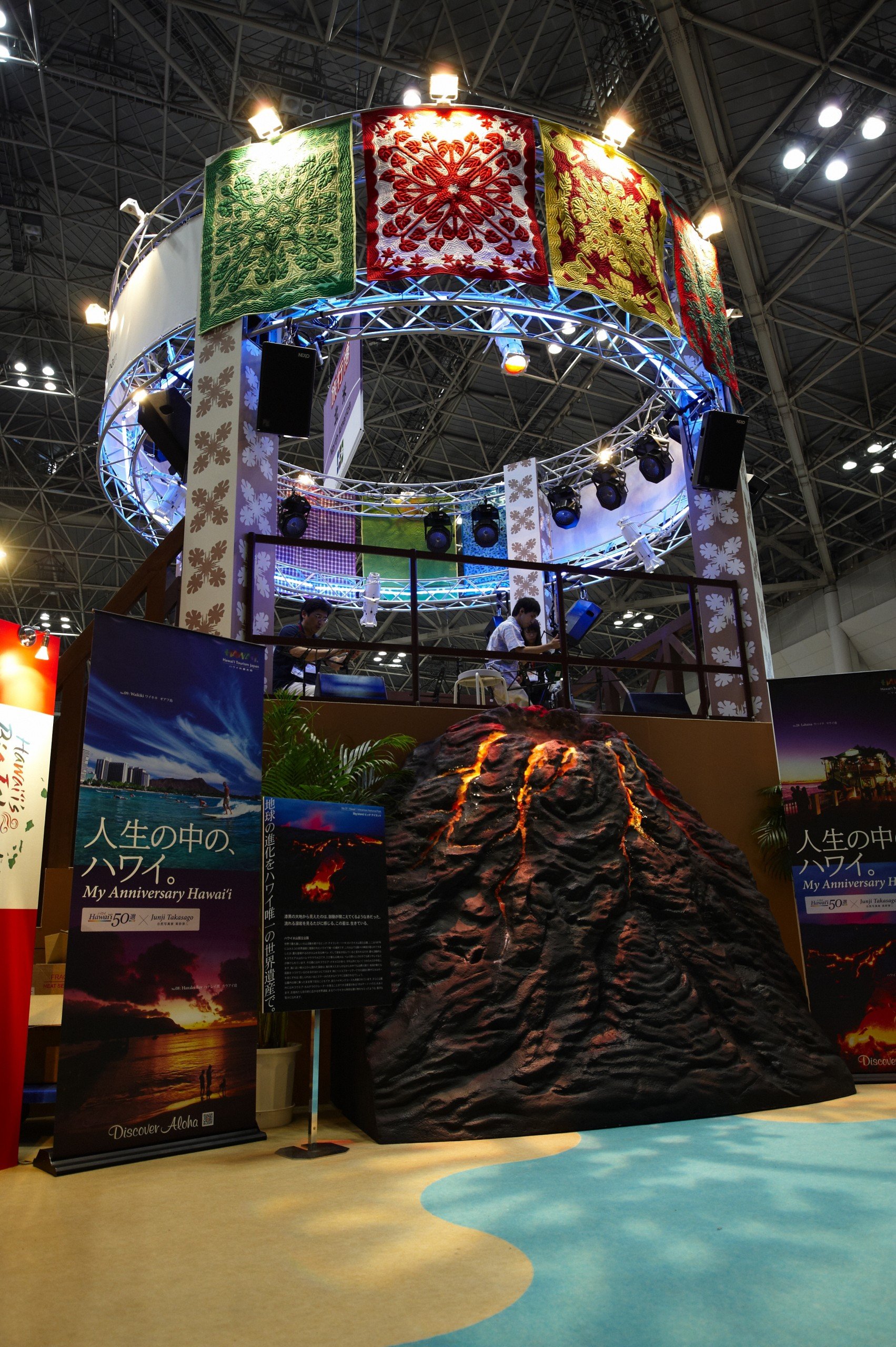

High on the stage of the Hawaii booth, overlooking the hubbub of Japan’s biggest travel fair, the musical group Manoa DNA launches into “Aloha You, Aloha Me.” It’s a catchy tune, sung mostly in Japanese, that has become the band’s signature song here in Japan, and the smiling, enthusiastic crowd gathered at the foot of the stage seems to know all the words.

The group’s performance brings business at the neighboring booths to a standstill. At the Canada booth, instead of watching videos of Nova Scotia on giant plasma screens, visitors swivel 180 degrees to watch the band and clap to the music. The Japanese women hosting the Las Vegas booth set down their brochures to dance and sing along. They cheer and flash shaka signs when the song ends. This might be Japan, but there’s a great deal of Hawaii at the Japan Association of Travel Agents Congress and World Travel Fair.

That makes Japan an excellent place to start talking about how Hawaii sells itself to the world. Japan, after all, is our most lucrative foreign market, and three of the most important players in that marketing effort are at the event. On the edge of the crowd is Takashi Ichikura, dapper in an aloha shirt and blazer. Ichikura-san, as he’s known to almost everyone here, is the director and principal owner of Hawaii Tourism Japan, HTJ, the state’s marketing partner in Japan, and the person most responsible for organizing Hawaii’s presence at the JATA fair. At the back of the crowd are the two key players from Hawaii: Hawaii Tourism Authority president and CEO Mike McCartney and his right-hand man, VP for brand management David Uchiyama.

They’re an odd couple: McCartney, the sensitive, soft-talking former politician; and Uchiyama, the taciturn numbers man and marketing guru. The industry consensus is that their good cop/bad cop routine, the mix of political sensitivity and strategic planning, has been one of the keys to reviving Hawaii’s battered tourism economy. Here’s how they’re doing it.

Old-School Marketing

Even in the digital era, marketing is sometimes just about getting in front of as many people as possible, and the JATA World Travel Fair is one of the largest tourism expositions in the world. This year, 71,740 consumers attended and, more important, so did 39,492 travel agents, tour operators, media and others in the travel industry. That makes the fair an extraordinary marketing opportunity, which is why HTJ invests so much time and money on its booth every year. It still works.

For example, HTJ used a contest at the fair to persuade nearly 5,000 consumers to complete surveys about how they choose a destination. Employing QR codes, the survey provided consumers with a link to HTJ’s new mobile website, resulting in 74,199 hits and 23,712 unique visitors, a 33 percent increase over the previous month. Exposure at the fair also boosted hits to HTJ’s regular website by 69 percent to 1,387,079 during the month. And, of course, tens of thousands of brochures were handed out at the booth, each offering a specific call to action.

For example, HTJ used a contest at the fair to persuade nearly 5,000 consumers to complete surveys about how they choose a destination. Employing QR codes, the survey provided consumers with a link to HTJ’s new mobile website, resulting in 74,199 hits and 23,712 unique visitors, a 33 percent increase over the previous month. Exposure at the fair also boosted hits to HTJ’s regular website by 69 percent to 1,387,079 during the month. And, of course, tens of thousands of brochures were handed out at the booth, each offering a specific call to action.

Beyond the raw numbers, the fair also generated the kind of good will that marketers love, even if they can’t measure it. All those people singing along to Raiatea Helm and Manoa DNA are priceless.

Like almost all HTJ programs, the fair also offered marketing opportunities for the state’s travel partners – hotels, wholesalers and attractions that depend on tourism. In fact, six Hawaii-based travel partners paid a nominal fee – helping offset the cost of the event – to have a table at the Hawaii booth. These included the Kaanapali Beach Hotel, Hilton Hawaiian Village and Kualoa Ranch. Travel professionals and consumers file past their tables collecting brochures and listening to the company pitch. HTJ also provides free brochure hosting for companies that can’t come to the fair.

Marketing partners like HTJ provide other essential services, like training and educating travel agents and wholesalers. HTJ, for instance, offers extensive destination training, both online and through seminars it conducts around Japan. Last October, HTJ collaborated with numerous Hawaii hotels and attractions to bring more than 200 Japanese travel agents to the Islands on a familiarization trip – or megafam. It’s much easier to sell a place when you’ve been there yourself. Similarly, in November, the Hawaii Visitor and Convention Bureau, HTJ’s North American equivalent, hosted a small group of travel writers on a trip to Oahu.

The JATA travel fair in Japan is also a good opportunity to see the competition. This year, more than 1,000 delegates from 90 countries gathered at nearly 900 exhibition booths. A stroll through the exhibition hall reveals that Hawaii doesn’t have a monopoly on good marketing ideas. The Croatian booth, for example, is a collaborative affair, with Croatia’s equivalent to HTA lauding the country as a tourism destination, and its version of DBEDT wooing Japanese investors. (The fair’s organizers awarded the Croatian representatives “best destination marketer” for 2010.) In the Yemen booth, visitors can change into Bedouin garb and pose for photos in an ersatz harem. Mexico, one of Hawaii’s most important tourism competitors, has a spectacular booth with multiple flat-screen displays showing videos of Chiapas, Oaxaca and the Yucatan. Not to be outdone by Hawaii’s performers, Mexico employed a full mariachi band, replete with balladeers and brass.

HTA president and CEO Mike McCartney spoke at a JATA symposium on how to increase global travel among Japanese people who live outside the Tokyo area.

Big exhibitions like JATA highlight one of the great challenges facing Hawaii: As a small, island state, we don’t have the financial resources to compete with entire countries such as Mexico or Australia, or large states like Florida or California. Even some cities, such as Las Vegas or Macau, have larger marketing budgets than Hawaii. Industry observers estimate Mexico’s tourism marketing budget at $200 million to $250 million a year. Florida’s destination marketing – split among many agencies – probably totals more than $150 million.

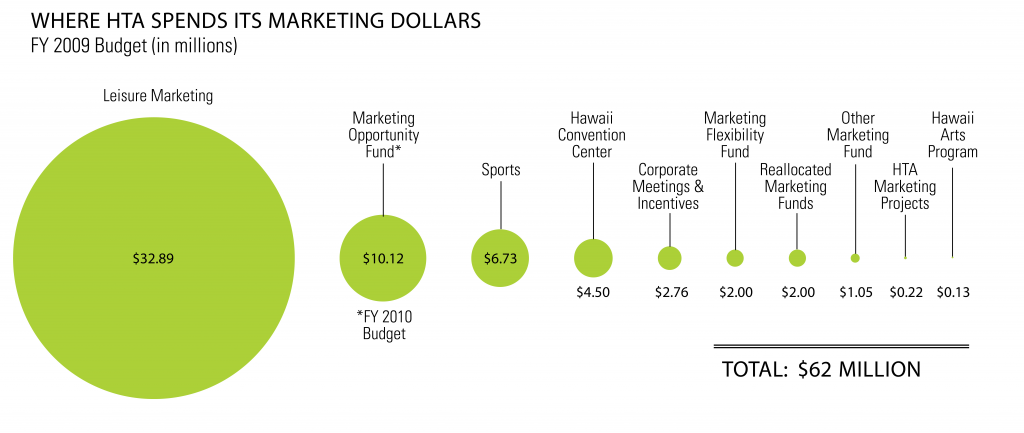

In contrast, the total marketing budget for the state of Hawaii in 2010 was $65 million, which had to filter through HTA, to the marketing partners such as HTJ and the Hawaii Visitors and Convention Bureau, down to the individual island chapters. Most insiders say this simply isn’t enough money. “We ought to be spending about $150 million a year instead of $60 million,” says Outrigger president and CEO David Carey.

Big events like the JATA fair aren’t cheap. It cost HTJ $48,326 just to rent the floor space in the exhibition hall for three days. Building and manning the booth, including the stage and the sound system, cost $111,657. Transportation, accommodations and nominal per diem for the performers ran another $41,350, even though HTJ was fortunate that much of the talent was already in Japan. Roll in HTJ’s staff time to plan for the event and to support the HTA visit, and the tab for JATA approaches a quarter of a million dollars. That doesn’t include the money spent by the travel industry partners or the cost of flying in the HTA board members and staff. There’s no way around it: Big-time marketing is expensive.

The Blitz

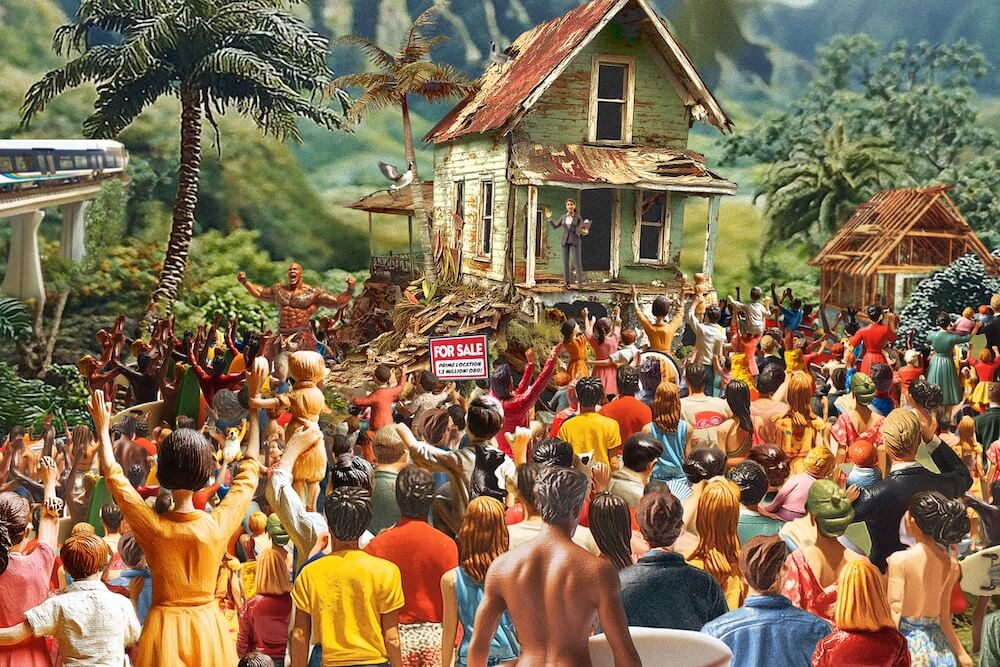

Although Japan is an important market for Hawaii tourism, it’s dwarfed by North America, particularly the U.S. West, which contributed about 2.8 million arrivals to Hawaii last year, more than twice as many as Japan. So, in 2009, when plummeting visitor counts threatened a crisis in Hawaii’s largest industry, it’s not surprising that the marketers looked to the West Coast. In the wake of the loss of Aloha Airlines and ATA, the question for the Hawaii Visitor and Convention Bureau seemed to be: How do we preserve and grow airlift? And from the marketer’s perspective, how do we do that and still maintain the integrity of the Hawaii brand? As HVCB president and CEO John Monahan points out, “We didn’t want to dilute its value, built over decades, by putting ‘Hawaii on Sale.’ ”

The answer was “The Blitz.” Jay Talwar, senior vice president for marketing at HVCB, ascribes its origins to a conversation HVCB had with Hawaiian Airlines and its ad agency. “They said to us, ‘What if we focus on one market and just saturate it with a cooperative marketing program?’ And we said, ‘That’s great, but what if we invited everyone – all the hoteliers, the attractions, the travel sellers, all of them – to come and really try to get the tide to rise?’ And Hawaiian was good enough to say, ‘That’s fine. We know we’ll get our share. If the pie grows, our slice grows with it.’ That’s the birth of The Blitz.”

Several HTA staff and board members also attended JATA, including the new chairman, Atlantis CEO Ron Williams (center.)

Talwar sketches out the thinking that went into the first trial run: “Let’s say we go to San Francisco for a whole month, and each week, we focus on a separate island.” The key, he says, was, for a month, to make Hawaii “unavoidable in that marketplace.” Doing that meant using every marketing tool available. It meant editorial visits to get the Hawaii story in local media – newspapers, magazines, radio and TV. It meant advertising: They cover-wrapped the San Francisco Chronicle and ran banner pages on its online version, SFGate. They put up billboards along the commuter routes of a demographic their analysis described as the habitual traveler. At night, they had “billboards” projected onto the sides of prominent buildings. They used social media and online contests to publicize special events. All of that drove traffic to the website of HVCB or an island chapter or a travel partner. “Basically, we did everything that you would do in Marketing 101,” Talwar says. “We just did it all at once.”

For later blitzes in Seattle, Los Angeles and again in San Francisco, HVCB fine-tuned its approach. In coffee-mad Seattle, marketers handed out free coffee to early morning commuters on the ferries, each week featuring coffee from a different Hawaiian island. The pitch: “You can actually go visit the farm where this coffee was raised. You can’t do that anywhere else in the United States.” Similarly, the second blitz in San Francisco took advantage of the city’s reputation as a culinary capital. “This time, we had a few guys with us named Roy and Alan and DK,” Talwar says. “It’s now connected with chefs and the farm-to-table movement. Now, we’re talking to San Franciscans in a language they understand. That got us a lot of great coverage in the local media.”

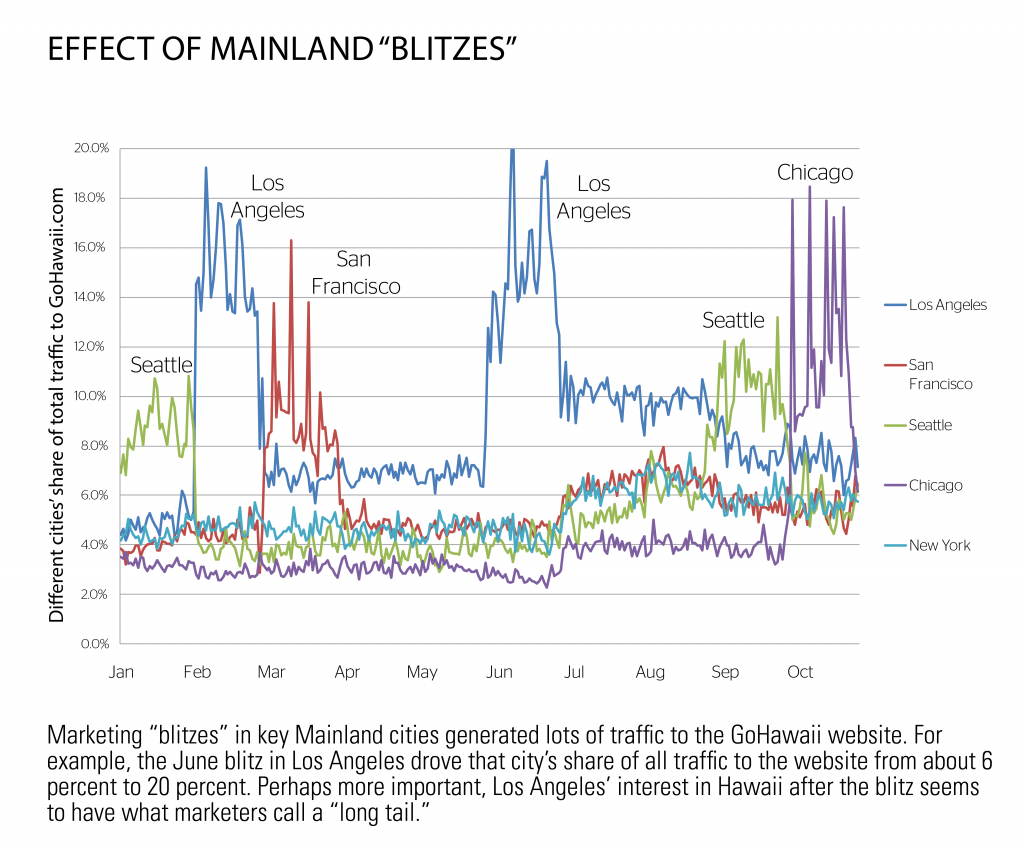

It worked. “We began measuring results 30 days out,” says Monahan. The steep spikes in visits to the HVCB website after the blitzes are unmistakable signs of marketing success. Perhaps a more meaningful measure is the level of participation among the travel industry partners. Monahan points out, “At one point, we had brand X; then X and Y; then X, Y and Z. Now, they all want to know as far in advance as possible what our blitz schedule is going to be so they can work that into their plans.”

The travel partners are more direct. “We use two metrics to measure marketing success,” says Jack Richards, CEO of Pleasant Holidays, the largest travel wholesaler to Hawaii. “One is brand awareness; the other is sales or passenger volume. And from our perspective, the blitzes have been tremendously effective on both fronts.” He also remarks on one of the keys to that success: Much of the money to pay for the blitzes comes from private industry. “You’ve got to understand that suppliers like me, we spent millions of dollars in matching funds to help drive visitors to the Islands,” Richards says. Exactly how much is difficult to ascertain, but, HVCB’s Monahan says, “We know the funding spent by these partners is a multiple of what we spent.” And HVCB has been spending between $1 million and $2 million per blitz.

Beyond Marketing

Much of what makes marketing work isn’t the flashy media campaigns or public relations bonanzas; it’s what happens quietly in the background, and one of the keys to the recent successes of HTA and HVCB is their growing use of data. While the whirlwind nature of the blitzes makes it seem like those decisions were made by the seat of the pants, in reality they were grounded on hard numbers. The target cities were chosen because the data showed they accounted for more than half of Hawaii arrivals. Just as important, as HVCB’s Talwar points out, most U.S. East Coast visitors also pass through these cities, so it’s critical that marketers preserve as much airlift from them as possible. “Protecting the West Coast hubs allows us to protect our East Coast markets as well,” Talwar says.

Similarly, good strategic data was behind almost all the tactics used in the blitzes. Extensive consumer surveys allowed HVCB and its ad agency to craft advertising and public relations material based on the lifestyles and interests of the target audience. Demographic data and customer profiling helped identify appropriate media outlets and event locations. Social media allowed the marketing professionals to track the effectiveness of blitz activities in near real time. New-age marketing is all about data.

Hawaii’s marketers increasingly rely on sophisticated private-sector specialists to develop and make sense of all these numbers. In addition to DBEDT analysts (who recently moved under the HTA roof), these include companies like Hospitality Advisors, a Hawaii-based company with a global reputation as a strategic tourism consultant; Smith Travel Research, a respected industry consultant providing competitive set surveys that allow HTA and its marketing partners to see how Hawaii tourism is doing compared to its major competitors; and Sabre Airline Solutions, the giant travel conglomerate, which provides critical airlift analysis.

Airlift data is particularly critical for an island destination like Hawaii. Our economy depends on having enough air seats and, as the loss of Aloha Airlines and ATA demonstrated, maintaining that airlift is complicated. As David Uchiyama, HTA’s No. 2 man, points out, prior to contracting with Sabre, the state’s marketers had no idea if an airline’s route was having problems. As a consequence, it had no way of knowing if the airline needed help. “With the use of Sabre Aviation,” Uchiyama says, “we can now look months in advance to see booking pace, what the load factors are, and what’s the average fare they’re charging. Now, we can go to them and say, ‘We see that the route’s not doing so well. How can we support it with some kind of marketing boost?’ ” Those sorts of conversations are now commonplace.

Another quiet factor in the recent success of HTA has been the teamwork of Uchiyama and McCartney. HTA is not without critics, and one of the main complaints has always been that the organization’s structure makes it easy prey to politics. Most industry partners say they would prefer a much tighter focus on marketing, and less emphasis on cultural and environmental programs, and other priorities. (The money to fund HTA, after all, doesn’t come from the general fund; it’s paid by hotel guests through the transient accommodations tax.) So, when McCartney was selected to run HTA, many worried about his lack of a marketing background. Starwood Resorts senior vice president for operations Keith Vieira readily admits he preferred Paul Casey, the other major candidate for the job. “Mike had legislative experience and community experience,” Vieira says. “Paul had industry experience.”

Yet Vieira, like other industry critics, have been pleasantly surprised by HTA’s performance under McCartney. “Looking back,” he says, “I would say Mike McCartney was a very good choice.” Partly, that’s because McCartney has been careful to delegate most of the marketing decisions to Uchiyama, whose marketing background at Starwood puts him in good stead with the industry. David Carey, the CEO of Outrigger and another long-time critic of the politics and organization of HTA, points out, “Under Mike, they have a pretty good team in place. And now David’s so much more involved on a higher level.” Both Vieira and Carey acknowledge that McCartney’s political gifts have been useful, too, and not simply in dealing with the Legislature. In fact, his sensitivity and political skills have probably been most on display internationally, where he’s helped transform HTA’s relationship with key travel partners. The best example may be how the McCartney/Uchiyama team dealt with the loss of Japan Airlines’ Narita-Kona flight.

McCartney tells the story this way: Last spring, after losing money on its Narita-Kona route for years, JAL announced it was shutting the route down. For Kona, the result would be devastating, not only because Kona would lose a steady stream of lucrative Japanese visitors, but because, besides Honolulu, Kona is the only international point of entry for the state. Without JAL’s international arrivals, TSA would likely close its temporary facilities there, probably for good. With that in mind, the next time he was in Tokyo, Uchiyama paid a visit to Sunichi Saito, then JAL’s executive officer for passenger sales and marketing. He asked Saito a simple question: “How can we help?”

Those four words changed everything. The next day, Uchiyama was summoned to JAL headquarters to meet with Kiyoto Morioka, JAL’s VP for international passenger sales. “We’ve been flying to Hawaii for 55 years,” Morioka said in astonishment. “This is the first time anyone’s asked us that.” What ensued was a frenzied effort by JAL and tour operators in Japan, and HTA, the Big Island Visitor Bureau, and travel industry partners here to work together to develop marketing and promotional campaigns to create enough demand to sustain the route. This unprecedented cooperation succeeded in raising JAL’s load factor by more than 20 percent – not enough, ultimately, to preserve the route (as part of its bankruptcy restructuring, JAL shuttered 40 percent of its international routes) – but enough to set a new tone in the relationship and create a model for how to market in the future.

That same sensitivity to the needs of travel partners was on display during a string of courtesy calls made by the HTA entourage after the JATA travel fair. Over the course of a day, Ichikura-san chaperoned McCartney, Uchiyama and the HTA board members through a string of corporate offices around Tokyo. Along the way, they visited with executives at airline partners, such as JAL and Delta; at major travel wholesalers, such as JTB and JALPAK; and with trade organizations like JATA and the Japan-Hawaii Tourism Council. These meetings, as you would expect in Japan, were frequently formal and stylized. They were also surprisingly candid, with each side volunteering inside information about corporate strategy or political challenges, swapping industry rumors, and asking for opinions and advice.

In the end, it always came down to those four words: How can we help?

During one of the symposia at the JATA conference this September, McCartney sat on a panel that discussed how to get more Japanese from beyond Tokyo to travel abroad. But, seeing JAL VP Kiyoto Morioka in the audience (a courtesy in itself, since the audience was mostly midlevel managers), McCartney took a question about how low-cost carriers were going to affect the market, and he turned it inside out.

“We appreciate all airlines,” McCartney said, nodding to Morioka, “but we want to say a special aloha to Japan Airlines. Your Kona flight did very well for many years. But, because of the downturn in the world economy, you came to us to apologize that you could no longer fly to Kona. You showed us pictures of your trips to Hawaii when you were a child and told us how important Hawaii was for you. We will never forget that. We’ll never forget the commitment that JAL has for Hawaii. And I wanted to say, ‘We’re the ones who should be apologizing for not coming to you sooner to help.’ Thank you so much for all you’ve done for Hawaii.”

When McCartney finished, Morioka and his small entourage of JAL executives stood and bowed deeply.

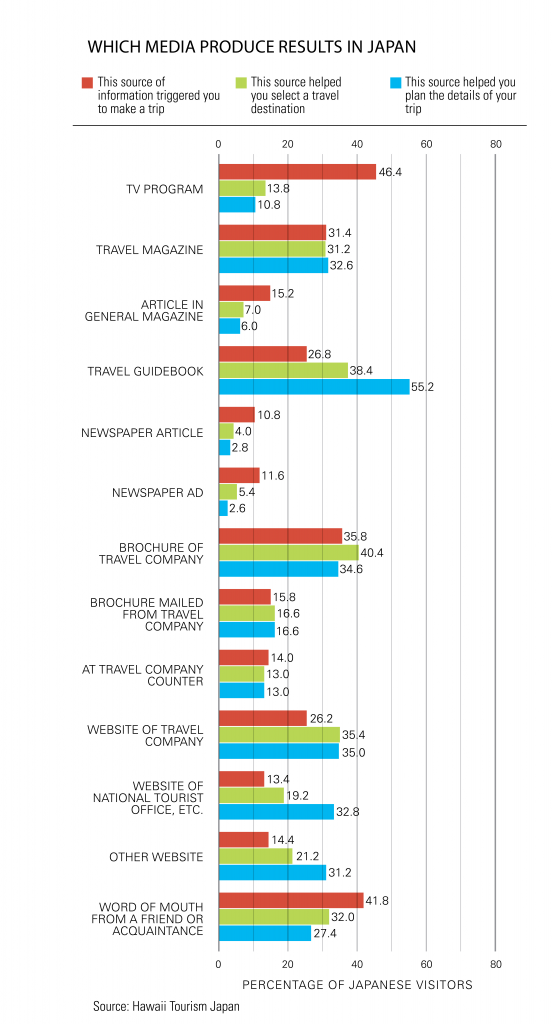

Which media produce results in Japan

Effect of mainland “blitzes”

Marketing “blitzes” in key Mainland cities generated lots of traffic to the GoHawaii website. For example, the June blitz in Los Angeles drove that city’s share of all traffic to the website from about 6 percent to 20 percent. Perhaps more important, Los Angeles’ interest in Hawaii after the blitz seems to have what marketers call a “long tail.”