Ride Along with Hawaii’s Longest Commuters

Short Commutes Also Present Challenges

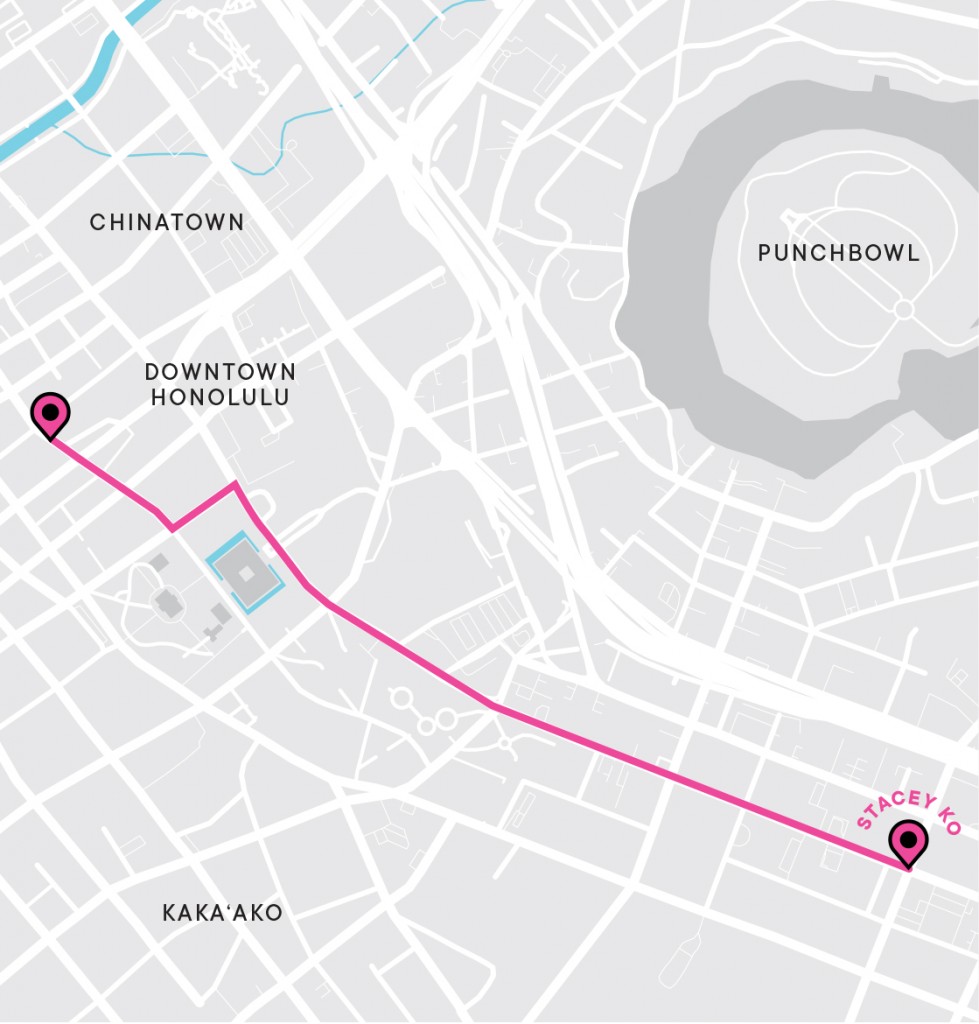

Years of taking the bus on the Mainland and in Hawaii have taught Stacey Ko that the only way to make her commute better is to make concessions. That might mean walking farther so she can take fewer buses to her destination or leaving her home earlier to ensure she doesn’t miss her ride.

The promotions director for Summit Media Hawaii recently started carpooling to work, but when she rode the bus, she left her house at 8:20 a.m. to make it to work by 8:45 a.m. She would spend 10 minutes walking to the bus stop on South Beretania and Pensacola streets where she would catch the 1 or 2 into Downtown. Those buses dropped her off a five-minute walk from her office. One trick was to catch a bus closer to her house to take her to the stop at South Beretania and Pensacola streets.

It takes a lot of practice to figure out the best buses to take and set a schedule – plus a backup plan, she says. “In the beginning, it’s all frantic, hectic, running around like a chicken with its head cut off.”

Buses come to Makiki consistently during morning rush hour, but if she woke late or if the bus broke down or was too full to pick up new passengers, Ko had to decide whether she’d risk waiting 10 more minutes in the hope another bus would come, or take a taxi or Uber – and spend more money. “It’s a gamble that you have to play with yourself. And sometimes you win, and sometimes you lose,” she says.

Traffic slows when it rains, so bus riders must schedule more time for their commute, Ko says with a frustrated groan. Also, the buses run on different schedules on holidays, weekends and on days when there are parades and events, so if Ko has to work, she plans her commute differently.

Learning these lessons has enabled her to enjoy her bus rides – she can watch YouTube, read her e-book or listen to podcasts – instead of stressing over them.

Today, she carpools in the morning with a couple of family friends and takes the bus home in the evenings. While the car ride takes about the same time as riding the bus, she likes that she can leave home later and be dropped off next to her office.

Say What?

Here’s what residents told Hawaii Business on social media about their commutes:

“Normally, it’s not bad. If there’s an accident, it can be awful considering the relatively short distance I travel,”

– a commuter who travels from Kaimuki to Downtown. The worst part: motion sickness during stop-and-go traffic.

“We take our son to school in Liliha, so the drive to Downtown after that is fast,”

– a commuter from Aiea, who enjoys the family time with three of them carpooling.

“Heavily affected by Downtown Honolulu rush hour,”

– a commuter who travels from Kapolei to Kailua by car pool to take advantage of the zipper lane, though the drive still takes more than 90 minutes.

“When you compare the distance (10 miles) to how much time it takes (45 minutes), it’s insane,”

– a commuter who puts up with the drive from Aina Haina to Downtown because the job is worth it.

“I get a workout when biking to work so I feel accomplished in the morning,”

– a commuter who bikes from Kakaako to Downtown.

“It’s my only option, seeing as I have no car or someone to carpool with,”

– a commuter who takes the bus from Salt Lake to Manoa.

Navigating Congestion

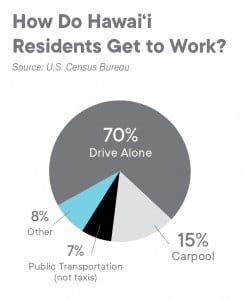

Many more Oahu residents drive alone than carpool or take public transportation. “We are a car-driven place on a very tiny island,” says Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell, adding that there are almost 800,000 vehicles registered on Oahu. With narrow corridors to travel in, congestion continues to get worse.

Oahu can’t build its way out of congestion, says Makena Coffman, a professor in UH Manoa’s Department of Urban and Regional Planning. “That’s kind of a general saying for if you have a high population density, the more roads you build, the more they’ll be filled, which is pluses and minuses.”

State and county officials agree that building new roads is not the best solution. They encourage people instead to become less dependent on cars and instead bike, walk, take the bus or ride the rail, Caldwell says.

The 20-mile rail is expected to have a ridership of 120,000 per day by 2030 and eliminate an estimated 40,000 car trips, says Ryan Tam, deputy director of planning, sustainability and environmental compliance for the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transit. Andrew Robbins, HART’s executive director, adds that one of the benefits of a fixed, elevated guideway is that the travel time is predictable. Commuters on the road don’t have that luxury.

The rail is not expected to be fully operational until 2025, though the first 10 miles will open at the end of 2020. Meanwhile, Ed Sniffen, deputy highways director of the state Department of Transportation, says the state has been making small-scale improvements to existing infrastructure to alleviate congestion. One example is the afternoon westbound contraflow lane on Farrington Highway in Nanakuli. More than 40,000 vehicles travel that stretch each day.

“The biggest thing for us is we want to make sure we put our investments where it’s going to give us the biggest bang for the buck,” he says. “And for us it’s going to be based on the volume of traffic or the number of users, and the condition of the facility in that area.”

State Rep. Andria Tupola, who lives in Maili, says many residents are grateful for that afternoon contraflow lane because it keeps traffic moving. Traffic is a big quality of life issue for west side residents – who often endure hourslong commutes into and from the urban core – because they cannot accurately gauge how long it will take to reach their destination, says state Rep. Cedric Gates, whose district encompasses Maili to Makua.

Gates and Tupola prioritize transportation and traffic. Tupola will even help police officers come up with solutions when accidents occur – even in the middle of the night – along Farrington Highway so that the two lanes heading in each direction are cleared faster.

“I explain to people it’s not OK,” she says. “You have to pick up your kids from A+ (after-school program), which you can only keep your kids at until 5:30, and if there’s one lane closure going westbound in the afternoon into Waianae, forget it, you’re not going to be able to get to your kids. You probably won’t get home until 7:30 or 8.”