Hawai‘i’s Housing Crisis Was Decades in the Making

A look at the policy decisions, external crises and social changes that gave Hawai‘i the most expensive housing in the nation.

It’s hard to believe now, but 30 years ago Hawai‘i had an oversupply of housing.

That’s when the state was mired in a decadelong recession triggered by Japan’s economic bubble crash (1991), a U.S. war (Desert Storm, also 1991), and Hurricane Iniki (1992). By the mid-1990s, “there was standing inventory of unsold homes,” says Stanford Carr, CEO of Stanford Carr Development. “We were in that predicament, as were all the major homebuilders here. We came off from doing 20 houses a month. Everybody was doing like a house a day, till it came to a screeching halt.”

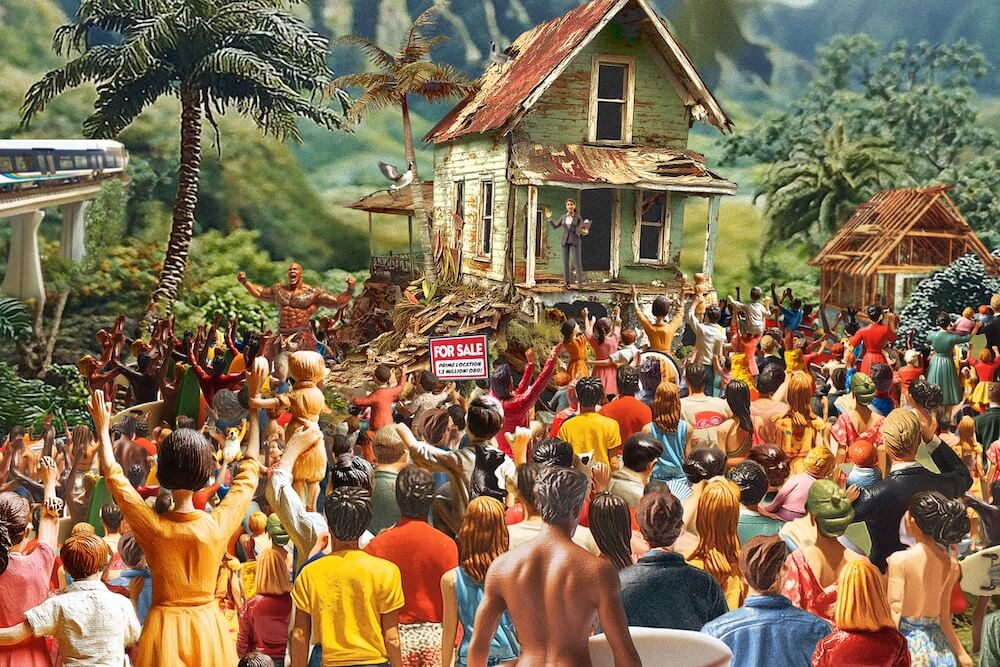

Today, the state is at least 64,000 housing units short, according to Carr. The problem is not exclusive to Hawai‘i: The U.S. has a nationwide shortage of at least 1.5 million housing units, according to the National Association of Home Builders, and more than half of the overall inflation in the economy has been due to the rising costs of housing. But Hawai‘i’s housing costs are the highest in the nation.

How did we get here?

Decreased Household Size

“As more people want to live independently, as people live longer and survive their spouses, as people choose to not get married or want smaller families, you need more housing units,” says Sterling Higa, executive director of Housing Hawai‘i’s Future, a nonprofit dedicated to ending the workforce housing shortage. “You need smaller units, too, like studios and one-bedrooms for people who want to live alone.”

In 1950, Hawai‘i’s population was 499,800, according to the U.S. census, with an average household size of 4.3 people. By 2020, the population had grown to more than 1.45 million, with the average number of people per family dipping to 3.38. Despite the drop in family size, Hawai‘i still has relatively large households; the national average is 2.53 people per household.

With the drop in the number of people inhabiting a household, the state would need nearly a third more houses than in 1950, even if the population had not grown at all.

There are also different expectations of housing today. “Many of Hawai‘i’s laborers 70 years ago were working menial jobs at plantations,” says Higa. “You look at those plantation houses, these are oftentimes 700 square feet or less, and those were three-bedroom homes. Someone buying a three-bedroom today probably wants more than 700 square feet.”

Today’s homeowners also desire parking spaces, which adds considerably to the cost of building a residence and eventually translates to higher rents and for-sale costs. “Structured parking costs like $55,000 a stall,” says Carr.

Was There a Golden Age?

Housing can certainly be built quickly. Shortly after World War II, the Mānoa War Homes project whipped up 522 two-bedroom and 478 one-bedroom units, providing housing for 1,000 active duty service members, veterans, and their families.

And other local development was brisk.

“The example I always give is Makiki,” says Higa. “Most of those buildings were built by small groups of local investors. So, let’s say, a few small-business owners, a doctor, a dentist, pooled some money. They got a low-interest loan. They had a contractor build a walk-up, and they took some of the units themselves, sold some units, rented some.”

He notes land was much less expensive back then because more of it was still undeveloped.

The demand for real estate in 1955, when Hawaii Business Magazine was founded, was very different from what it was even four years later, notes Higa. “Prior to statehood, Hawai‘i was not even really a national market for real estate. After statehood, it becomes a national, then international real estate market, with successive waves of various investors — Canadians, Japanese, Chinese, and Brazilians.”

After statehood, “capital investment poured in to build the tourism engine that we think of today, but was also accompanied by a large demographic shift, with lots of people moving in from the mainland relative to historic trends,” says Trey Gordner. Gordner is a policy researcher at UHERO, UH’s Economic Research Organization; an advocate for affordable housing; and a member of the ‘Ewa Beach Neighborhood Board.

“For the people who were already in Hawai‘i, there was a rising concern for issues that echo down to today, such as cultural loss, environmental degradation, and carrying capacity.”

The result was Hawai‘i’s State Land Use Law, adopted in 1961. It set four land-use districts: urban, rural, agricultural, and conservation. To administer the law, the state Legislature established the Land Use Commission.

“The idea of zoning, of government having some influence over patterns of development, has existed for a very long time,” says Gordner. “Rome had a plan. What makes the modern U.S. distinct is what we call Euclidean zoning, where you have separation of uses and the prioritization of single-family homes over all else.” For example, he notes that you can build a single-family home in an apartment district, but not the other way around.

Another American style of zoning is a strict separation of commercial and residential spaces. “We’re retreating from that a fair bit now with mixed use, but we’re still in the early stages,” he says.

Within this American context, “Hawai‘i imported a zoning scheme that was really best suited to wide-open spaces,” says Gordner. “We grafted in a lot of things that might be fine in the Great Plains, for instance, but that don’t make a lot of sense when you have the coast on one side, the mountains on the other, and you can’t just continue to grow into the next county.

“So, we have a lot of natural barriers, but we also have a lot of artificial barriers. Now, just because we have those artificial barriers doesn’t mean that we should tear those down, necessarily. As I said, there was a reason why, and there is a policy consensus that lasts to this day, why we don’t build as much.”

The challenge with this tight level of zoning – and it is tight, with only 4% of land in the state zoned for residential housing – “is that people from outside the state have income that is not bound by the local economy and can afford to pay higher housing prices than people who are constrained by the local economy,” Gordner says. “It’s very hard … in a constitutional free market system, to prevent those people from coming in, and in attempting to do that through land-use policy, the by-product is you end up hurting the people who are already here.”

The Controlled Growth Movement

During the years George Ariyoshi was governor, from 1974 to 1986, a restrictive approach to development became the norm. “A core component of Ariyoshi’s platform was managed growth,” says Higa, “and he was running against Frank Fasi, the mayor of Honolulu, who was a very big proponent of growth.”

During the Ariyoshi administration, state government was “making it pretty difficult, intentionally, procedurally, to do much [building], especially on a grand scale,” says Gordner.

The 1978 Hawai‘i State Constitutional Convention marked another notable shift, with concerns for prioritizing water use for Native Hawaiians and preserving historical and archaeological sites.

“All together, this effectively constrained development – as it was intended to do,” explains Gordner. “It was a policy success in the sense that it was what people wanted at the time, and it did what it was supposed to do. And it’s still doing that today.”

In Carr’s opinion, it would have been better to have left land-use decisions at the county level. “It’s their own backyard, their responsibility as far as shaping their long-range planning for each of their respective counties, as opposed to the state having that authority. It’s contributed considerably to the cost and supply of housing here.”

Permitting Slows

“Thirty years ago, I could get a building permit in a day and a half. Now it could take as much as a year or more,” says Carr. “Castle and Cooke, they’re building Koa Ridge. It took them 17 years to get through the entitlements. When they initially petitioned the Land Use Commission, they were projecting to sell homes in the $300,000 range but by the time they broke ground, they had to sell their single-family homes for a million dollars.”

Back in 1955, the year Hawaii Business Magazine was launched, 4,840 private residential building permits were granted in Hawai‘i, and by 1959, that had increased to 8,932 permits. Compare that to 2023, when only 3,117 permits were authorized, says Paul Brewbaker, an economist at TZ Economics.

Says Brewbaker: “Let’s look at 2008 to 2023. The average is 1,000 fewer units authorized by building permit annually in the entire state of Hawai‘i than were authorized … without the use of computers, in the year Hawaii Business Magazine was established.”

Brewbaker estimates that in the 1950s, Hawai‘i was building the equivalent of 4% of the existing housing stock on average every year. In other words, the number of new housing units was 4% on top of the existing inventory every year from the 1920s until 1975. But for the last 50 years, it has been barely 1%. And, Brewbaker says, “People ask, ‘Why is there a housing shortage?’”

Brewbaker stresses the goal is not to build up recklessly but to get a balance of responsible growth. “Ninety-five percent of the land in Hawai‘i is not in the urban land district, and a little more than half of the land in the state’s urban land district is urbanized. So the perception is we’re paving paradise to put up a parking lot, and the reality is, we could nearly double the amount of urban land use within the existing footprint, and 95% of Hawai‘i’s land would remain in the conservation and agriculture districts.

“You’ve seen the bumper stickers, ‘Keep the Country Country.’ Mine is, ‘Make the City City,’” says Brewbaker. “They are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they’re complementary.”

A Long-Delayed Rail System

Then-Honolulu Mayor Neal S. Blaisdell suggested rail as part of a mass transit plan in 1968.

The project planning came and went with various leaders, but a stake went through the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation (HART) in 1992, when the City Council, after two 5-4 votes in favor, voted 5-4 to reject a 0.5 percentage point surcharge on the state’s general excise tax that would have helped to pay for rail’s construction.

“Honolulu had an opportunity in 1992 to start doing a rail that would have interconnected the city, brought down transportation costs, and allowed for more [urban] development,” says Higa. The city finally broke ground for the Honolulu rail transit project in 2011.

“Housing and transportation are integrally related,” Higa explains. “Transportation is 15% to 20% of most people’s household spending. One of the primary ways that a city or a county can save people money is by reducing their transportation costs.”

Carr says he would like to see “equitable, transit-oriented communities, especially around the rail stations. What we need to do proactively is the infrastructure assessments – sewer, water, drainage, power, traffic mitigation – to install the infrastructure ahead of rail being installed.”

Development of a Second City

In 1977’s general plan, the City and County of Honolulu designated the ‘Ewa area as O‘ahu’s secondary urban center.

Gordner notes that while the idea of a second city was to take pressure off the urban core of Honolulu, in practice, “polycentric cities are hard to pull off. You can think about a moment in time when we might have made the political decision to allow the center to keep growing up, allowing the first ring of suburbs to grow up more modestly into towns, as opposed to the subdivisions as they are. That is a more organic, natural way for cities to grow.”

Creating a low-density second city, he says, commits people to using the H1 freeway if they still work in central Honolulu. That means people now have farther to travel for work, and that bind has increased with the commitment to rail.

Do We Suffer from Overpopulation?

Is it possible there are simply too many people living in the state?

“No, we could build a ton more housing,” says Higa. “It’s definitely a housing shortage. The fact that people have been complaining about overpopulation in Hawai‘i for 200 years tells you that it’s less about population than it is about housing. Do you hear anybody complaining less [about housing] over the last eight years, when the population has declined?”

Between July 1, 2022, and July 1, 2023, the state of Hawai‘i’s population decreased by an average of 12 people per day – or about 4,000 people during those 12 months – according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And that drop was prior to the Maui wildfires, which caused an additional exodus from the state. The previous 12 months – July 1, 2021, to July 1, 2022 – the State of Hawai‘i’s population decreased by 19 people a day.

Carr notes that more than half of the housing demand in Hawai‘i is for market units above 140% of the area median income. “What that tells you is that we’re just supply constrained. We’re not building to keep up.”