Hawaii’s Best Paid Executives

And How Their Pay Is Determined

There is always a collective gasp and some outrage when the pay of top executives is publicized. In these economically challenging times, many people are angry that the CEOs of big corporations are paid so much more than the average Jane and Joe.

However, leading a large company or serving on its board comes with complex challenges, potential liability and, in the post-Enron era, the need to maintain public trust.

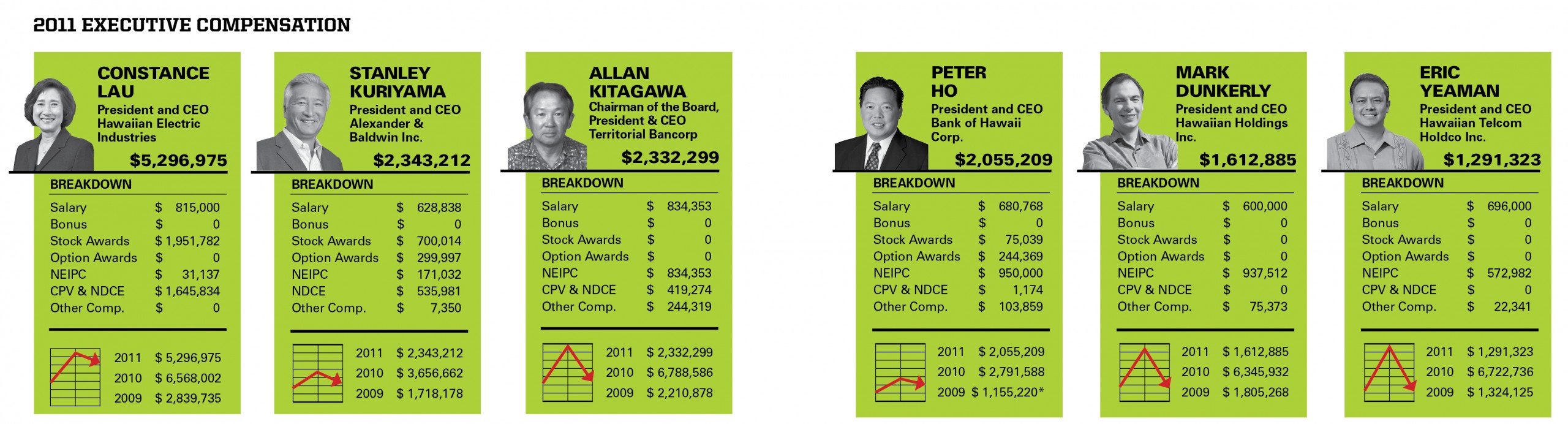

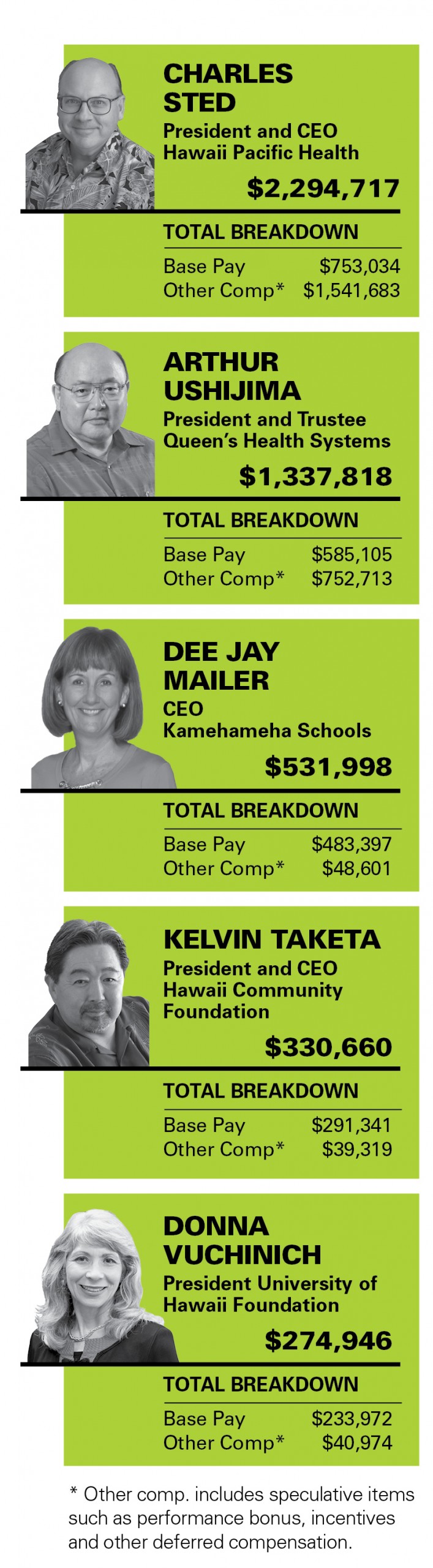

The Securities and Exchange Commission requires publicly traded companies to report the compensations of their five highest paid executives. Using the most recently filed SEC proxy statements, Hawaii Business ranks the six highest paid executives of Hawaii’s publicly traded companies, each with a compensation package of at least $1 million in 2011. We also list some of Hawaii’s highest paid nonprofit leaders, using the latest filings of IRS Form 990.

Companies say they carefully consider how much to pay their executives and often solicit outside advice. More stringent reporting requirements and shareholder control were imposed by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which was signed into law by President Obama on July 21, 2010. For instance, the act provides shareholders with a nonbinding “say on pay” and corporate affairs.

The act also recognizes the importance of outside consultants, giving boards of directors’ compensation committees the authority to hire independent compensation consultants.

Compensation consultants are not required at any company. However, according to James Kim, managing director of Frederic W. Cook & Co., the consulting firm that advises Hawaiian Electric Industries and Hawaiian Holdings, the holding company for Hawaiian Airlines, the compensation committees of most publicly traded companies in Hawaii and elsewhere choose to retain an external consultant to provide market data and advice on the structure of compensation plans and agreements.

“We usually prepare studies using both a custom peer group of similar companies, as well as third-party surveys,” says Kim, who works out of the firm’s San Francisco office. “This report is presented to the compensation committee and we usually develop recommendations based on this data and the company’s compensation philosophy.”

HEI spokeswoman Shelee Kimura says her company’s executive compensation is developed using industry peer data and is heavily based on performance.

“Much of the target amount, between 45 to 60 percent, is ‘at-risk’ and not guaranteed,” explains Kimura. “By tying compensation to performance, the executive compensation program focuses our leaders on meeting goals that benefit shareholders, customers and the community.”

For example, “approximately 60 percent of the target amount for (HEI CEO Constance Lau) depends on meeting performance goals. Of the total shown in the proxy, the majority of the stock compensation is not paid out yet and is only an opportunity to earn it in the future.”

Likewise, a change in pension value is not an amount that was actually received, but a theoretical calculation that fluctuates year to year based on changes in interest rates driven by the overall economy. In the end, what executives receive from their pensions may be higher or lower than the theoretical calculation.

HEI says its executive pay is designed to be at or near the median of its relevant peer group of companies, and compensation is reviewed annually by an independent firm that analyzes proxy statements and advises shareholders on how to vote on “say on pay” proposals.

How effective is “say on pay” if the shareholders’ approval or disapproval is not binding?

“ ‘Say on pay’ has become far more influential than we initially thought,” Kim says. “Failure to obtain majority support can lead to shareholder litigation and embarrassment for the company. The Dodd-Frank Act has led to enhanced levels of disclosure and heightened awareness of risk.”

Meredith Ching, senior VP of Alexander & Baldwin, said in the company’s most recent proxy statement that A&B received very strong approval from “say on pay.” She reported that nearly 98 percent of the shareholders eligible to vote approved A&B’s compensation practices.

“Seventy-one percent of Stan Kuriyama’s stated compensation is performance-based, and therefore ‘at risk,’ ” Ching reported in the proxy statement, “and it only gets paid based on how the company performs or how the company stock performs.”

According to the proxy statement, Kuriyama has made a concerted effort to control his compensation, resulting in his compensation being significantly below the median compensation for his peers. In fact, the statement says, market competitive data shows that his compensation is in the bottom quartile of his peers.

Each of the six companies on our list of highest paid CEOs says it retains an outside compensation consultant to conduct an external, independent review of its executive compensation. Additionally, all say they have instituted “pay for performance” models when setting their compensation packages.

“Say on pay” and shareholder oversights do not apply to nonprofits, but they face their own checks and balances over executive pay.

The Dodd-Frank Act does not apply to nonprofits, but the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 led to new IRS rules on the compensation of nonprofit executives. Sarbanes was a direct response to the corporate and accounting scandals of Enron and Tyco in 2001 and 2002, and, like Dodd-Frank, its provisions apply only to publicly traded corporations.

After Sarbanes, the IRS created the Rebuttable Presumption of Reasonableness Test as a roadmap for nonprofit boards in setting their executives’ compensation.

“The IRS set out this test made up of factors such as independence, obtaining comparable data, examination by the board of the documentation and decision-making in the executive compensation determination process,” says Kate Lloyd, general counsel and VP of operations of the Hawaii Community Foundation. “If you get audited or if someone raises the question about executive compensation and you’ve met all these factors, the burden of proof is then on the IRS to determine if the compensation is unreasonable. What the test is really doing is forcing the board to think of how they’re setting compensation.”

Public reaction to executive compensation is often stronger for nonprofit leaders than for-profit company leaders.

“In reality, I think the general public’s view of nonprofits is that it’s charity work, so instead of having a salary comparable to your counterparts in the private sector, you get these intrinsic rewards to make up for the money you’re (not earning),” says Kelvin Taketa, president and CEO of the Hawaii Community Foundation. “But that’s not a good thing to believe, because executives of nonprofits who have very, very challenging jobs are leaving the sector, partly because of burnout, but partly over financial considerations.”

Taketa strongly advocates that, when determining executive compensation for nonprofits, peer-group comparisons should also include for-profit companies.

“Sarbanes made it clear for the first time that when a nonprofit is seeking salary comparisons, it doesn’t have to be limited to the non-profit sector, but can look to similar for-profit entities to establish reasonableness,” says Taketa. “This is so important because when you’re hiring an executive, you’re not competing in the job market with only other nonprofits. You’re competing with the private sector, too. You want to look for the best people out there and pay according to the job responsibilities whether it’s for-profit or not-for-profit.”

Taketa adds that most nonprofit organizations do not have separate compensation committees, since they tend to be smaller and don’t have the same scale as publicly traded companies. Instead, the executive board on a nonprofit often serves as a personnel committee overseeing executive compensation. Also, nonprofit boards rarely hire outside compensation experts. Although the Hawaii Community Foundation has used an independent compensation consultant for specific situations in the past, it does not regularly use one.

Nonprofits face more challenges than for-profit companies when trying to base compensation on “pay for performance.” In the private sector, clear and immediate metrics often can be identified, but the impact of nonprofit work sometimes cannot be measured for years.

“For instance, organizations like the Boys & Girls Club that are trying to keep kids in school by working with them from middle school, will not see measurable results until years later, when the students graduate from high school,” says Taketa. “Pay-for-performance metrics typically don’t work really well in the nonprofit sector because, often times, the impact or results of the mission are not things that are going to be felt immediately and sometimes are difficult to measure, unlike measuring profit and loss.”

But, Lloyd says, changes are being made in the area of incentive compensation.

“The IRS has made it clear that incentive compensation for nonprofits is OK. You can set the metric that you’re going to expand your program into five different communities in 18 months and if you do, then you’ll get extra pay,” she says.

Taketa adds that incentive compensation and cash bonuses are much more acceptable now and are helping blur the lines between the private and nonprofit sectors.

2011 Executive Compensation

*This was Ho’s total compensation in 2009, when he was president. Allan Landon was CEO that year, with total compensation of $1,368,723.

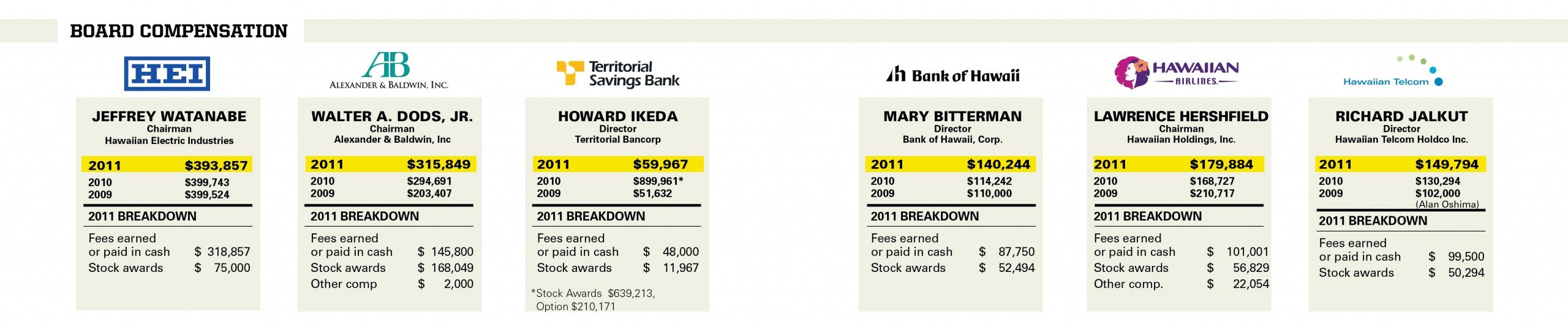

Board Compensation

Non-Profit / Foundation Executive Compensation (2009-2010)

* Other comp. includes speculative items such as performance bonus, incentives and other deferred compensation.

Inside the Numbers

The federal Securities and Exchange Commission requires companies to report overall compensation of their top five executives using these categories. “Salary” is obvious, but here’s an explanation of the other categories:

Bonus

“Cash awards that are based on satisfaction of a performance target that is not pre-established and communicated,” says a report by the national law firm of Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman and published in the Bloomberg Corporate Law Journal. These discretionary bonuses are different from NEIPC bonuses (see below).

Stock awards

The stocks’ value is the fair-market price at the time they were given to the executive.

Option awards

This is a speculative amount, based on mathematical models, of what executives might earn by exercising their stock option awards. These awards allow the executive, in the future, to buy stock at a fixed price. Sometimes, the executive makes a lot more money than this estimate, because the value of the company’s stock rises faster than expected. Sometimes, the executive decides not to exercise these options because the price of the company’s stock has fallen and the options have become worthless.

CPV

Change in pension value and

NDCE

Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Earnings. These categories quantify “the yearly increase in the actuarial value of all defined benefit and actuarial plans and any above-market or preferential earnings on nonqualified deferred compensation,” according to the Pillsbury law firm’s report.

NEIPC

Nonequity Incentive Plan Compensation. Usually includes cash bonuses that are not tied to the value of the company’s stock, but that use other predetermined measures such as return on assets or return on equity.