Hawaii State Government Slow to Pay

K.D., A General contractor on Oahu, has a hint of dismay in his voice when he talks about not yet getting fully paid for a job completed at the end of 2009.

Hundreds of thousands of dollars are still owed despite 10 months of back-and-forth calls and e-mails, says K.D., who asked that his real name and initials not be used because of who the client is.

The client is withholding the check because K.D.’s company didn’t provide a materials certification for a minor part of the project. The thing is, K.D. says, he wasn’t informed that the documentation was needed until well after the project was completed. He’s had difficulty getting certification from his supplier, which has to comb through its own records.

K.D.’s client? The state of Hawaii.

“It’s a frustration on our part, but we just have to work around it,” says K.D., who asked to remain anonymous because he fears his criticism might hurt his chances when bidding on future state jobs.

“They’re the only people with money right now.”

Other state contractors, including many nonprofit social-service groups, share the same complaint: The state doesn’t always pay on time. For nonprofits, the problem is compounded because the weakened economy has left them with fewer private donations.

Leaders at both for-profit and nonprofit organizations say the state’s slow payments seemed to increase as the state’s own finances took a hit during the downturn.

“It’s gotten a lot worse,” says M.J., an executive at another construction company that does both general and subcontracting work.

He says he’s been owed more than $500,000 for more than six months, including payment that the state is holding up until unrelated work by another subcontractor is corrected and inspected.

“I call every day to find out what’s happening.”

The contractor is like many people interviewed for this article, who say they will only speak if they can remain anonymous. They fear speaking out may produce a backlash and lessen their organizations’ chances for getting future government work.

They also say competitors might use their comments to paint them as difficult to work with, or that general contractors won’t include them in bids for fear they will be blackballed from state work.

One large nonprofit reported having to rely on a loan to meet expenses after waiting for more than three months to get paid. “Whether you are a nonprofit or profit-making entity, you’re counting on timely payments to keep things moving ahead. When there are delays, that really does impact an organization,” says the head of the group, a long-time Hawaii organization that provides social services.

“We have a payroll that needs to be met and bills that need to be paid.”

The National Council of Nonprofits recently compiled a list of government contracting abuses and put late payments at the top.

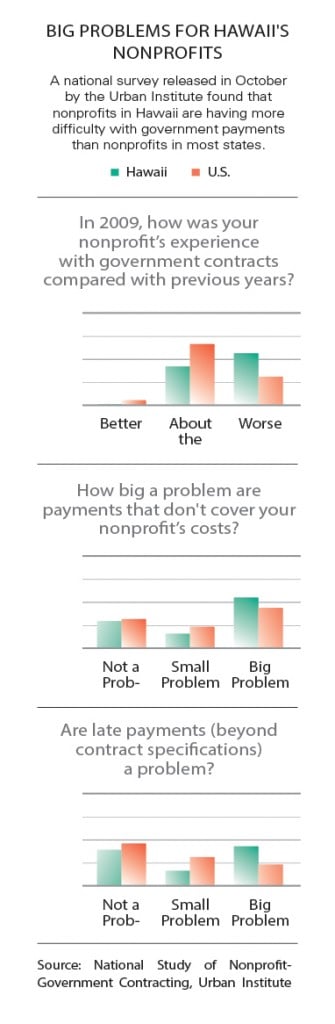

A nationwide survey by the Urban Institute in 2009 found that Hawaii ranks 15th worst when it comes to paying nonprofit human-service providers too slowly.

The survey said 39 percent of Hawaii organizations reported that late state payments were a big problem. The national average was 24 percent.

Half of the nonprofits surveyed in Hawaii said they’d experienced late payments from government contracts, with payments taking 90 days or more to reach them. The survey also found that most nonprofits thought their experiences with government contracting had deteriorated in 2009.

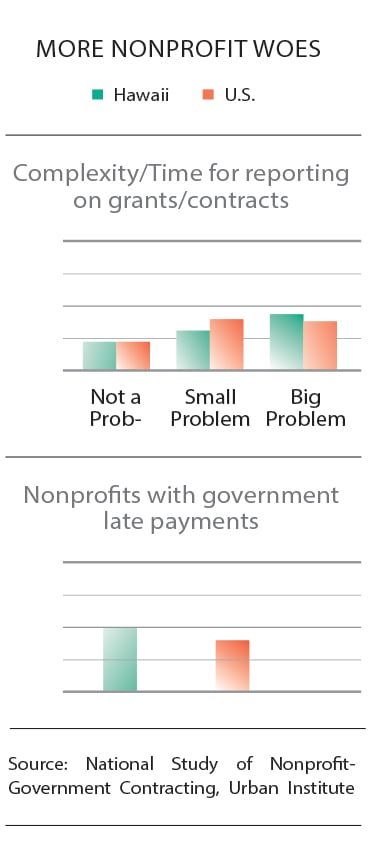

The Hawaii Alliance of Nonprofit Organizations released the report in October and called for changes, including speedier payments and less complex reporting requirements. The report also noted that more than half of the local nonprofits said payments weren’t covering their costs.

Laura Robertson, Goodwill Industries of Hawaii CEO and president, says she’s come to expect state payments to take three months or more.

“Over the last year, it has been more difficult because of the budget shortfall,” she says. “In some instances, we’ve delayed hiring staff or filling a position that’s been vacated to manage our cash flow.”

She says some of the tardy payments occur because an organization Goodwill is working with hasn’t been paid; in other cases the agency itself is waiting for a quarterly budget allocation.

Also, extra paperwork is often required, such as documentation on work progress and milestones. For one contract, Robertson says, her staff has to document nine different milestones for each client, creating a mountain of paperwork.

“When we have to float these payments for government, we’re talking about carrying a quarter of a million dollars,” she says.

“In good times, we’ve always had that paid in 30 days, maybe 45 to 60. But 90 is unusual. It’s hard to stretch that far.”

Lowell Kalapa, head of the Tax Foundation of Hawaii, sits on a nonprofit board that’s had budget problems because of overdue payments from the state.

“They’re trying to make do at the expense of their vendors,” Kalapa says. “This is much worse than it usually is. Everyone is kind of biting their nails.”

Private contractors report similar stories. They say that while they understand government needs to be a good steward of taxpayer money, there must be more efficient ways to make sure work is being done correctly.

Avoiding state government work isn’t a feasible option, contractors say, because residential and other private-sector jobs dried up during the recession.

The University of Hawaii Economics Research Organization notes the economic downturn hammered the construction industry, with receipts shrinking by roughly a third from 2007 to 2010.

From November 2007 to November 2010, the number of employed construction workers in the state shrank by more than a quarter, making it one of Hawaii’s hardest hit industries. But government construction work rose 20 percent during the first half of 2010.

UHERO’s latest forecast is for government infrastructure projects to maintain a level that’s roughly one-half higher than the average between 2005 and 2009.

Some contractors wish they could quit state jobs, given the paperwork and potential for slow payments. They say belated payments don’t seem to occur as frequently with county projects, but it depends on the agency. They generally say there is no problem with federal payments.

Complaints about state payments come in regularly to the Subcontractors Association of Hawaii, according to president Tim Lyons.

“I get prompt-payment complaints all the time,” he says. “Government would get better bids if it didn’t do this.”

In the past, part of the problem was general contractors holding on to payments. He says a law that went into effect in 2007 cleared up this problem, requiring all money paid to a prime contractor be disbursed to subcontractors promptly. The law included a penalty if a procuring agency or prime contractor failed to pay within 10 days of an invoice. But some agencies, including the University of Hawaii, have been exempted from the law, Lyons said.

Lyons and others credit former state Comptroller Russ Saito for pressing agencies and departments to make sure timely payments were made so that money flowed quickly into the economy. They also say some of that progress has slipped in the past year and a half.

Part of the problem was caused by state furlough days and layoffs. Lyons says other problems may lie with contractors who haven’t worked for the state in years and aren’t familiar with all the forms required to get paid.

“To do government work as a contractor you really have to be geared up for it,” he says.

It doesn’t help that procurement processes can vary from department to department, says Karen Nakamura, head of the Building Industry Association of Hawaii. Experienced contractors can generally navigate through the system, but now, “government work is the only kind of work that’s available,” Nakamura notes, which means a lot of inexperienced contractors.

However, delayed-pay complaints are coming from both experienced and not-so-experienced contractors. Nakamura says there is no excuse for delayed payments if contractors do the job and all the paperwork correctly.

She says many of the problems are with so-called retention or retainage payments, which are typically withheld until the project owner is assured the work is completed to specifications. Some contractors say pending retention payments as a percentage of accounts receivable have climbed dramatically.

Progress payments, made periodically during construction, are not as big a problem, according to contractors.

Making sure government dollars are well spent also slows down payment processing, as does using nongovernment construction managers to oversee projects. K.D. says these managers sometimes don’t communicate well on what documentation is required.

“It seems they are really picky now,” he says. “They want you to dot the i’s and cross the t’s.”

Says M.J., “On some jobs that I have, it basically comes down to personnel in certain departments.”

He says 99 percent of payments come through fine, though the ones that are pending are significant. “I thought I was better off doing government work,” M.J. says. “But now I don’t know.”

A perhaps larger problem is change orders. A Honolulu contractor says many retention payments are delayed when there are large change orders. Funding for the work may not have been appropriated and the project might be stopped while waiting for the money.

“It may hold up the whole rest of the job,” he says. “If it’s a legitimate change, you go ahead and do the work.”

But problems occur when cash-strapped agencies can’t come up with the money out of their own budgets or if state government is slow to release project money.

“That added money has to come from somewhere,” says Lyons. “Sometimes that has to go back to the Legislature.”

That scenario presents another set of problems, given the budget gaps faced by legislators and administrators. Departments may not want to admit a project went over budget in seeking more money, contractors say.

Contractor M.J. says he’s had retention payments go uncollected for as long as five years. The vendors can bill interest or get attorneys involved, but K.D. says most people don’t go that route for fear of hurting future chances for work.

“If you charge them interest it makes them look bad, and you know what happens next time,” he says.

The situation may change as Gov. Neil Abercrombie’s new administration settles in, given his pledge to seek solutions from government workers and make the state more efficient. Abercrombie also wants to quicken Hawaii’s economic recovery, and putting more state money into the private sector would help that recovery.

It also appears the new governor is aware of the late payments to both nonprofits and for-profit vendors. One of Abercrombie’s first acts after being sworn in on Dec. 6 was to announce he would release $23.7 million from the Rainy Day Fund to pay off past-due bills submitted by nonprofits. That included $350,000 owed to Catholic Charities of Hawaii, $300,000 to the Kapahulu Center, and $150,000 each to the Moiliili Center and the Waikiki Community Center.

Abercrombie noted that his administration would work expeditiously to move the funds through the state procurement process and pledged to get the money to the organizations as quickly as possible.

As Abercrombie prepared to take over in late November, his staff said he was going to address obstacles in the procurement payment process. Part of the new governor’s economic plans rest on stoking the economy to raise tax revenues.

“Slow payment from the state is much more than an inconvenience,” said a statement released by Abercrombie’s staff just prior to the inauguration.

“When dollars aren’t flowing smoothly into the private sector there are payroll problems, credit challenges and it puts a strain on the overall business climate.”

Big Problems for Hawaii’s Nonprofits

More Nonprofit Woes