Hawaii State ERS Underfunded by $7 Billion

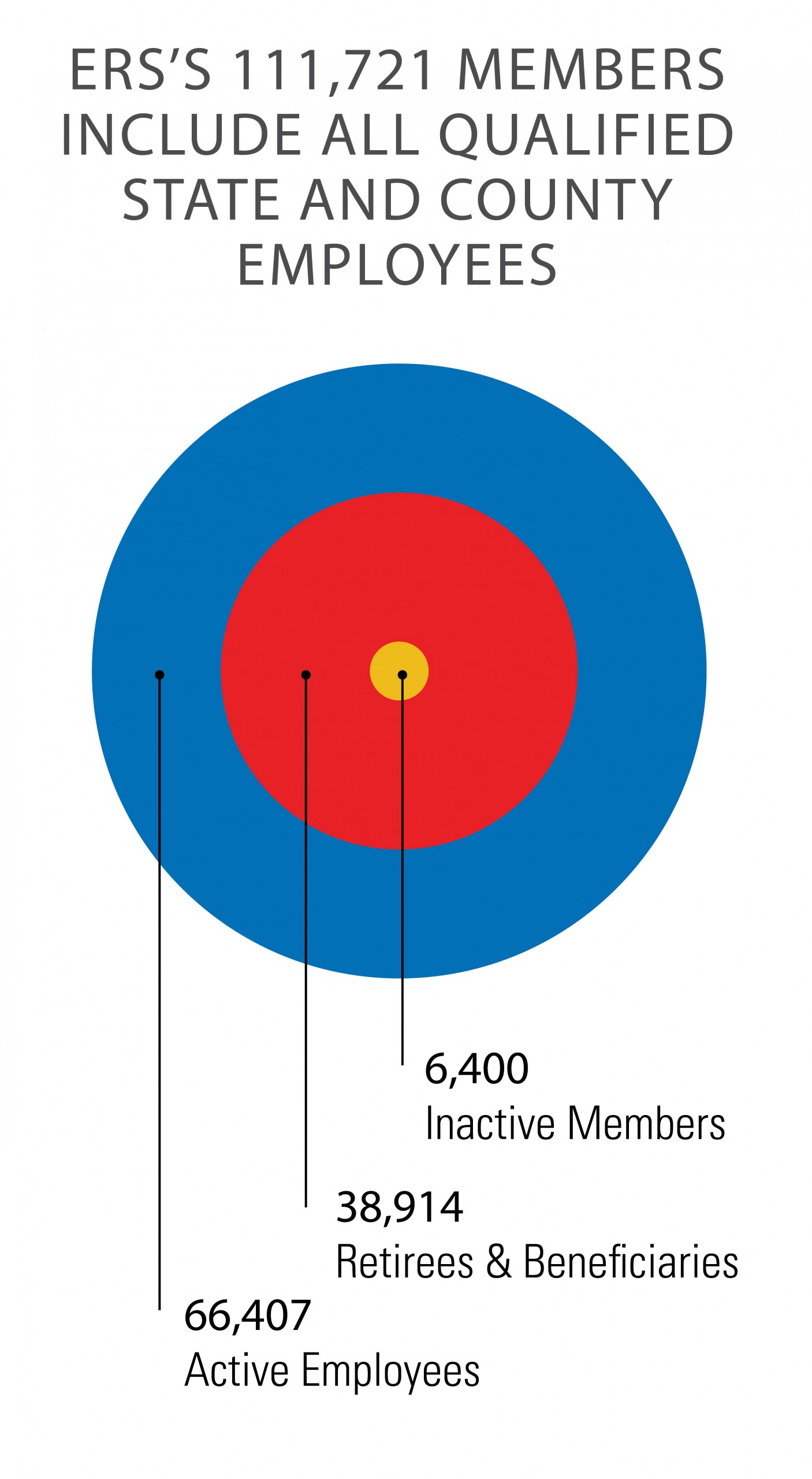

The state got just what it was expecting in its Christmas stocking. Unfortunately, it was another lump of coal – more bad news about the state of Hawaii Employee Retirement System, which covers both state and county employees. In its five-year report, the actuary firm of Gabriel Roeder Smith & Company claims the system’s future liabilities now exceed the assets set aside to pay for them by $7.1 billion. That’s nearly $5,500 for every man, woman and child in the state.

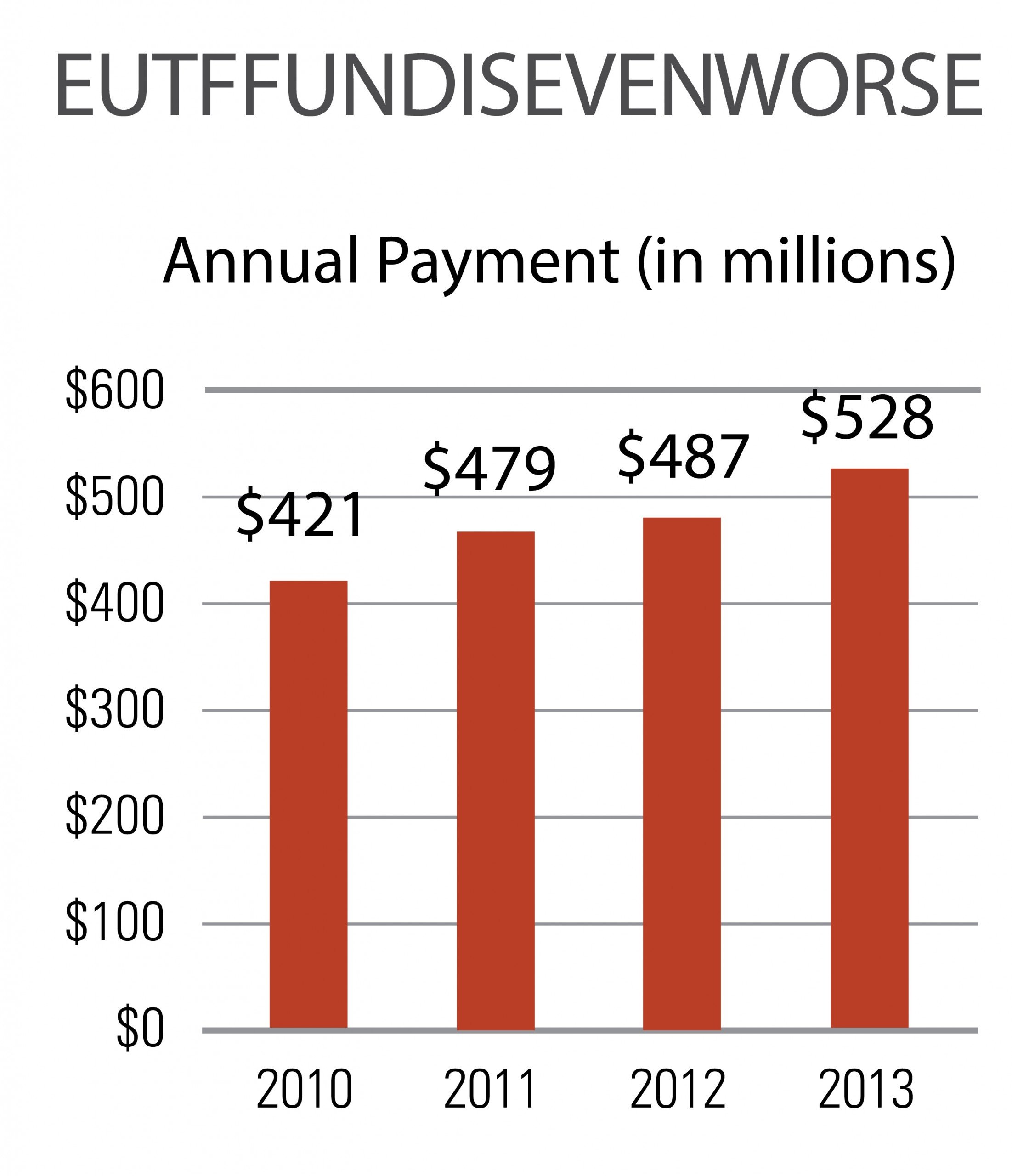

Worse still, because of the arcane rules governing actuarial accounting, those figures don’t fully incorporate the system’s huge market losses in 2008 and 2009. Consequently, an additional $1.5 billion will be added to the state’s unfunded liability over the next two years. This means the state’s legally required contribution to the pension system will increase to more than $671 million a year by 2015.

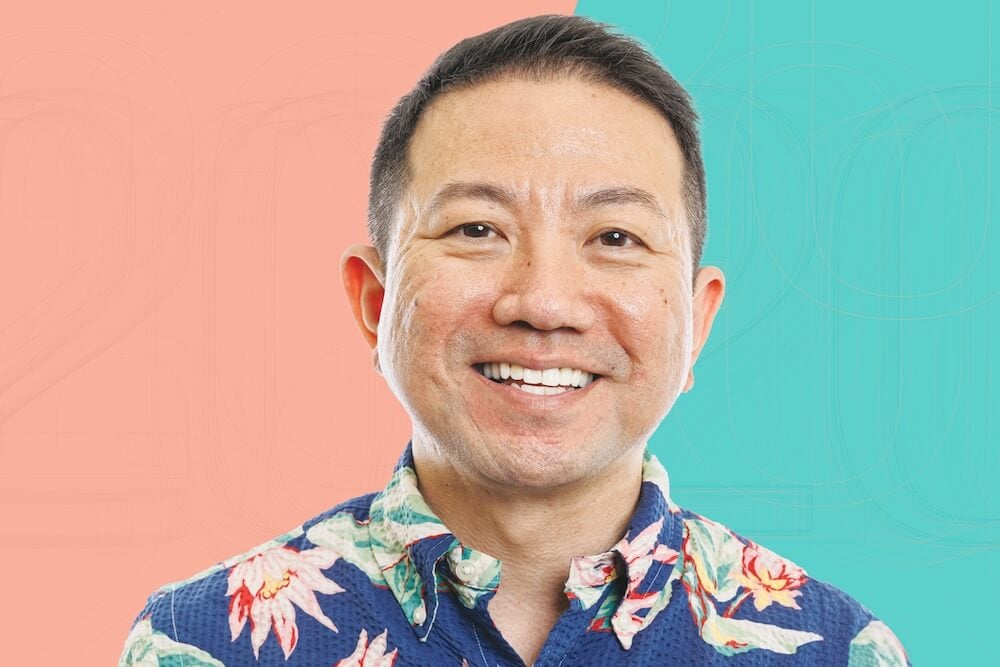

The actuary’s findings were hardly a surprise to those familiar with the state’s pension system. In fact, Wes Machida, the conscientious new ERS administrator, spent much of the holiday season playing Grinch, briefing legislators and members of the incoming administration on what to expect in the report.

Digging a Hole

One of the most remarkable aspects of the current shortfall is how quickly it has grown. As recently as 2000, the pension system covering government workers for the state and Hawaii’s four counties was 94 percent funded. This year, by some measures, the funding ratio has declined to less than 60 percent, and the prospects for paying down the deficit appear more and more remote.

There are a couple of factors behind the relentless growth of the pension liability. The first is that, like most state retirement systems, the ERS is a defined-benefit system. In other words, state and county employees are guaranteed set benefits when they retire, based on how many years they have worked and their average salaries at the time of retirement. In addition, those benefits, once earned, are guaranteed by the Hawaii Constitution; they cannot be reduced, even in response to a fiscal crisis such as the state’s recent budget shortfalls. This is typical of defined-benefit systems. In 1979, when New York City went bankrupt, it reneged on hundreds of millions of dollars owed to contractors and bondholders, but never failed to make pension payments to retirees.

There are a couple of factors behind the relentless growth of the pension liability. The first is that, like most state retirement systems, the ERS is a defined-benefit system. In other words, state and county employees are guaranteed set benefits when they retire, based on how many years they have worked and their average salaries at the time of retirement. In addition, those benefits, once earned, are guaranteed by the Hawaii Constitution; they cannot be reduced, even in response to a fiscal crisis such as the state’s recent budget shortfalls. This is typical of defined-benefit systems. In 1979, when New York City went bankrupt, it reneged on hundreds of millions of dollars owed to contractors and bondholders, but never failed to make pension payments to retirees.

To pay for these enormous liabilities, the ERS – again, like almost all state pension systems – is a “pre-funded plan.” In theory, enough assets are set aside and invested each year to generate income to offset future liabilities. A pension is said to be “fully funded” when current assets are projected to pay for all future liabilities. Funding comes from three sources: employee contributions, employer contributions and interest earned on the system’s assets. Each contributes to the shortfall.

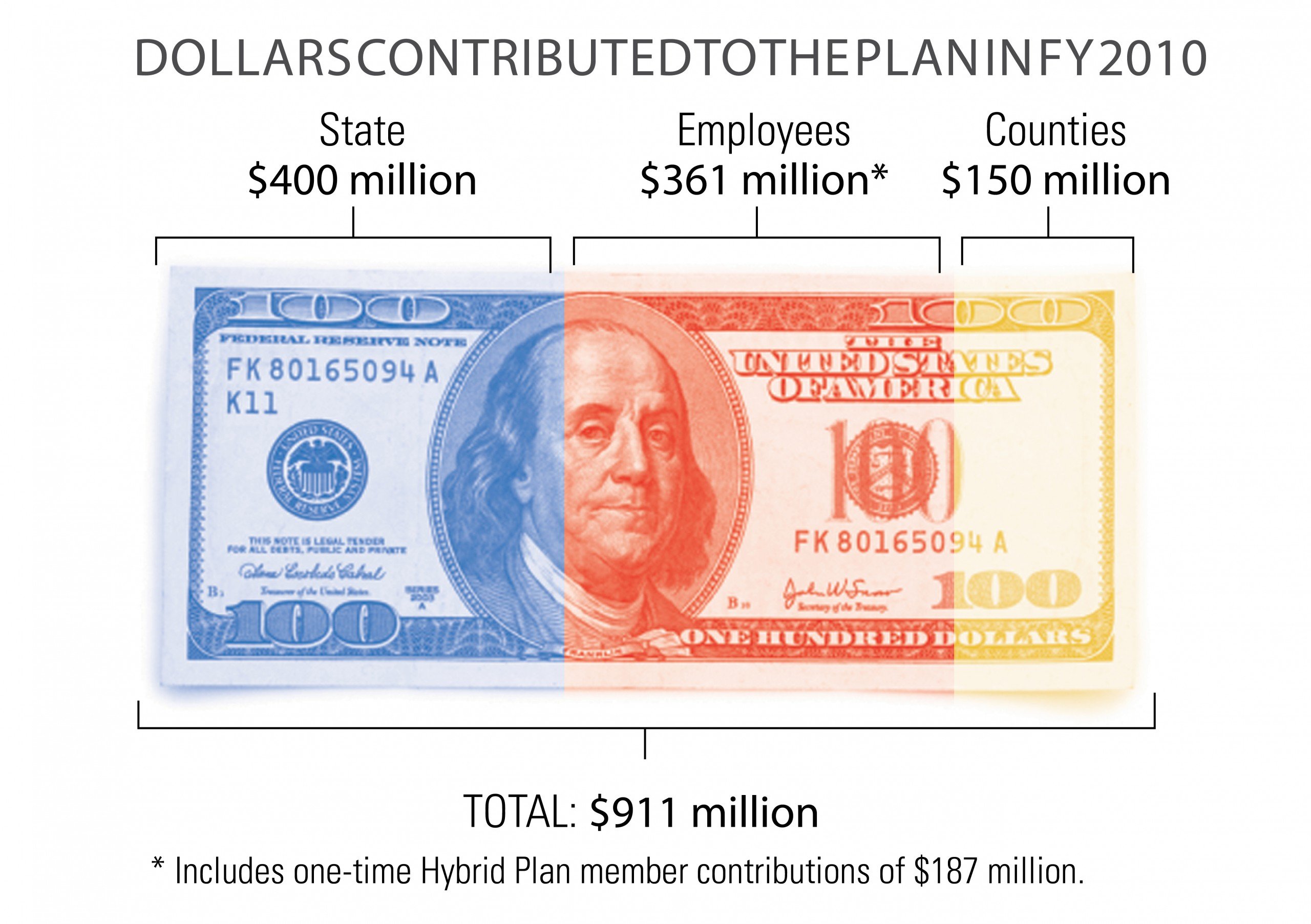

In Hawaii, employee contributions are set by law at around 12 percent of payroll for firefighters and police, and 6 percent for other employees. According to Machida, employee contributions amounted to $361 million in 2010, which included $187 million in one-time payments as members changed plans within the system, leaving $174 million in normal employee contributions.

The amount paid by state and county employers is also governed by statute, which prescribes an “actuarially required contribution,” or ARC, sufficient to fully fund the system within 30 years. As lifespans have increased and payrolls have expanded, the counties’ and state’s required contributions have soared: In 2000, the ARC was about $175 million; by 2010, it had reached more than $550 million – $400 million for state employers, and in excess of $150 million for the counties. Even so, the unfunded liability has grown.

The system’s investment earnings scenario isn’t any rosier. Here, too, state law predominates, setting the pension fund’s anticipated rate of return on its investments at a robust 8 percent. But this number has little bearing on the system’s actual earnings. In the past 10 years, returns only reached as high as 8 percent four times. In fact, the system’s market earnings over the past decade have averaged only 2.8 percent, not even keeping pace with inflation. With such inflated earnings expectations, not only is income overestimated, but future liabilities are underestimated.

The system’s investment earnings scenario isn’t any rosier. Here, too, state law predominates, setting the pension fund’s anticipated rate of return on its investments at a robust 8 percent. But this number has little bearing on the system’s actual earnings. In the past 10 years, returns only reached as high as 8 percent four times. In fact, the system’s market earnings over the past decade have averaged only 2.8 percent, not even keeping pace with inflation. With such inflated earnings expectations, not only is income overestimated, but future liabilities are underestimated.

Assuming Liability

There are, in fact, a slew of other actuarial assumptions that affect the size of the pension system’s liability. For example, Machida notes, the system assumes an average life expectancy of 83 years. Every year, though, actual life expectancy increases. “The average life span of a female schoolteacher is over 90 years,” Machida says.

Other assumptions are more financial. “For example, there were more promotions than expected,” Machida says. “Salary increases were projected at 3 percent or 4 percent; but professors, for example, at one point were given a 9 percent to 11 percent raise. Police officers were getting a 9 percent raise.” Similarly, more benefits were added to the pension system without consideration for how we would pay for them. It will be hard to get back these costs.

Distressingly, most strategies to address the system’s weaknesses hinge on manipulating some of these manini-seeming assumptions: extending the age of retirement; changing the definition of “base pay”; changing the way cost-of-living allowances are calculated. Because the benefits of retirees and existing employees are protected by the state constitution, any changes can probably only apply to new hires. That means the cost of addressing the system’s long-term liability will have to be spread over a small pool of members.

Distressingly, most strategies to address the system’s weaknesses hinge on manipulating some of these manini-seeming assumptions: extending the age of retirement; changing the definition of “base pay”; changing the way cost-of-living allowances are calculated. Because the benefits of retirees and existing employees are protected by the state constitution, any changes can probably only apply to new hires. That means the cost of addressing the system’s long-term liability will have to be spread over a small pool of members.

Machida says these assumptions aren’t the main reason the state’s unfunded liability has grown so dramatically. He ascribes most of the increase to an old rule that allowed legislators to seize any annual earnings over 8 percent and apply them to the state’s ARC. In 2001, the worst year, the state used approximately $150 million of these “excess” earnings to help balance the budget. Between 1999 and 2003, according to Machida, more than $350 million in excess earnings were diverted from the pension system. “In 2004, with the assistance of (then) Governor Lingle, we introduced legislation to take that away,” Machida says. But the damage has been done. “If that money had not been taken,” he says, “the system today would be almost fully funded.”

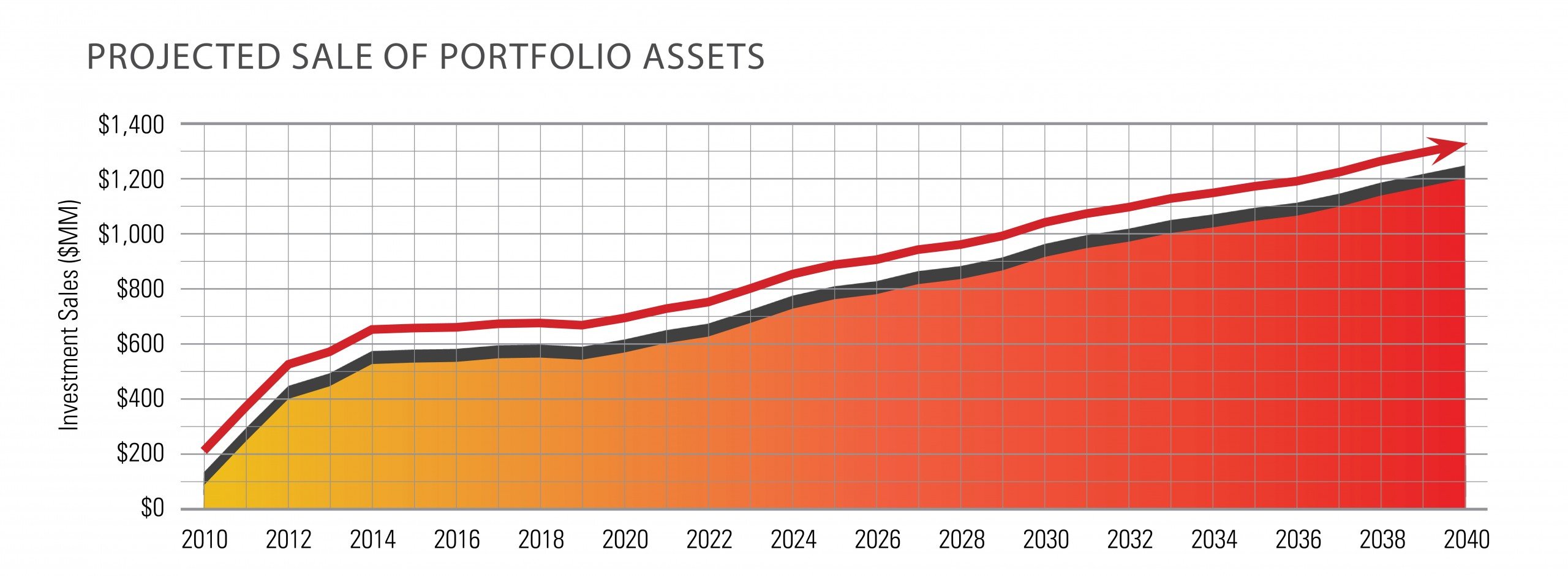

Whatever the proximate causes of the pension-system shortfalls, the effect is a vicious circle: When current income and contributions aren’t enough to pay current benefits – a condition that began in 2006 and is projected to accelerate rapidly for the next five or six years – the only option is to sell off portfolio assets to cover the difference. In 2011, the ERS is projected to cannibalize nearly $200 million in portfolio assets; by 2020, that figure could reach $600 million a year. That’s the opposite of a “pre-paid pension fund.”

Whatever the proximate causes of the pension-system shortfalls, the effect is a vicious circle: When current income and contributions aren’t enough to pay current benefits – a condition that began in 2006 and is projected to accelerate rapidly for the next five or six years – the only option is to sell off portfolio assets to cover the difference. In 2011, the ERS is projected to cannibalize nearly $200 million in portfolio assets; by 2020, that figure could reach $600 million a year. That’s the opposite of a “pre-paid pension fund.”

How to Fix It

Fixing this problem is going to take time. The formula, according to Machida, is straightforward. C+I=B: contributions plus investment earnings must equal benefits paid. To make that equation balance, each variable will have to be tweaked. First, the employer’s contribution must increase. “This isn’t an option,” it’s a necessity, Machida says. Failure to  comply with state law would have disastrous effects on state and county bond ratings.

comply with state law would have disastrous effects on state and county bond ratings.

The scale of the increases necessary will be painful. The recent actuarial report by Gabriel Roeder Smith already raises the ARC to 19.7 percent of payroll for firefighters and police, and 15 percent for general employees, which should yield $671 million a year by 2015. Even that won’t be sufficient. To generate the extra $182 million needed, the actuaries recommend increasing those figures to 27.3 percent and 18.8 percent, respectively, which will yield an additional $43 million. The ARC already constitutes about 10 percent of the state’s general fund budget; it’s hard to see where the additional revenue will come from to pay for the increase.

The interest variable in the pension equation also comes into play in the actuaries’ calculation. By assuming an additional 1 percent yield on the system’s investments, they add another $117 million to the pot. (Although they don’t mention it in their report, raising the assumed rate of return also lowers the current unfunded liability.) But, as Machida points out, raising the targeted investment return comes with higher levels of risk, which further could jeopardize ERS assets.

In fact, making up the state’s unfunded liability on the left side of the pension equation is probably impossible in the long term. That means legislators are left with the politically difficult option of reducing retiree benefits. Machida outlines the possibilities:

• Raise the retirement age;

• Increase the number of years it takes employees to become vested;

• Change how final salaries are calculated; and

• Constrain future payroll growth.

Some version of all of these reductions will likely be necessary, but can the Legislature make them happen?

To begin with, as Machida points out, the benefits of existing employees are protected by the state Constitution. That means new hires will likely bear the brunt of any changes in benefits. Calvin Say, the longtime Speaker of the House, acknowledges the challenges faced by the Legislature. “I’ve introduced a number of bills to deal with the unfunded liability,” he says. “One that I had was to increase the retirement age from 55 to 60 so you can contribute to the trust fund longer. But you can’t address these changes with present employees. You can’t change this for the current retirees. It’s all going to be based on new employees.”

Kalbert Young, the Abercrombie administration’s incoming director of the state Department of Budget and Finance, makes much the same point. “I would say that the governor is interested in looking at what are the available means for resolving the liability issue,” he says. “Admittedly, though, it’s a very big number; and given the condition and depth of the problem, our timeline for resolving it may not be in the near term.” In other words, future state and county employees will be paying the tab for generations.

Kalbert Young, the Abercrombie administration’s incoming director of the state Department of Budget and Finance, makes much the same point. “I would say that the governor is interested in looking at what are the available means for resolving the liability issue,” he says. “Admittedly, though, it’s a very big number; and given the condition and depth of the problem, our timeline for resolving it may not be in the near term.” In other words, future state and county employees will be paying the tab for generations.

That’s assuming today’s politicians can enact the necessary changes. Machida points out that, because they will likely only affect new hires, any prospective reduction in employee benefits are probably not subject to collective bargaining. Nevertheless, it’s difficult to envision the Legislature enacting major reductions without at least the tacit support of the public unions, by no means a sure thing. House Speaker Calvin Say remarks on how difficult it’s been trying to make these kinds of changes in the past: “For me, it’s been a sincere effort to try to control both the employers’ and the employees’ contributions,” he says. “But present employees do not understand that. They don’t want Calvin Say to force them to pay more for their pension contribution. But something’s got to give.”

Say remains optimistic. “Overall, I feel very confident, because, at the end of the day, the state government is obligated to fulfill its responsibility. So, yes, we’ll address that unfunded liability one way or the other. It will probably be through the guise of taxation.”

The Big Picture

“But time is of the essence,” says Machida. That’s because, as glum as the Gabriel Roeder Smith report seems, it may still understate the size of the problem. To understand why, it helps to put Hawaii’s retirement system in a national context. Since 2000, the number of states with fully funded pension systems has declined from 26 to four, according to a recent report by the Pew Center on the States. Hawaii is in the bottom quartile, one of 19 states described as having “serious concerns.” Remarkably, Pew data do not even include the effects of the Great Recession of 2008. Once those losses are incorporated into the picture, the perspective will be much worse.

Despite its baleful conclusions, the Pew report is squarely in the mainstream of actuary standards. It relies on the states’ own analyses and draws its conclusions using normal actuarial accounting procedures. There is a growing number of analysts, though, who believe that traditional actuarial accounting and its assumptions are part of the problem and help mask the true scale of the states’ pension crises. The most inflammatory of these is Joshua Rauh, a researcher at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, whose 2010 report suggests the states’ total unfunded liability may be several times larger than the findings in the Pew report. For example, he predicts Hawaii’s ERS will go broke in 2020.

Not surprisingly, Rauh’s conclusions have been largely discounted in the public pension community. “Among public pension actuaries,” says Keith Brainard, executive director of the National Association of State Retirement Agencies, “I think you would find the overwhelming perspective that Joshua Rauh’s findings and recommendations are inappropriate.” Even ERS administrator Machida – by no means an apologist for the status quo – downplays Rauh’s conclusions: “The ERS is not going to run out of money in 2020.”

But Rauh isn’t alone in raising questions about the size of the unfunded liabilities facing state pensions. For example, Andrew Biggs, of the American Enterprise Institute, uses a standard financial process called “options pricing” to reach much higher figures. In the case of the Illinois State Employees’ Retirement System, his analysis more than doubles the state’s total liability, from $23.8 billion to $47.3 billion.

Applying the same formula to Hawaii’s total liability swells our unfunded liability from $7.1 billion to more than $14 billion. Of course, the calculation isn’t that simple. It’s worth noting, though, that even pension actuaries are beginning to look at other ways of measuring pension liabilities. All of these suggest that our total liability is higher than the $18.8 billion actuarial valuation in the Gabriel Roeder Smith report. Rauh, basing his discounting rate on 30-year Treasury notes, calculated Hawaii’s total liability at $24.2 billion. The state’s own actuaries calculated a total liability of $21.5 billion when they used the market value of assets instead of the traditional actuarial method. Pessimism is clearly becoming part of the mainstream.

In fact, the actuary’s report to the ERS board in December included some startling language. Under the heading, “What does this all mean?” the report states: “If the assumptions are met for all years beginning July 1, 2010, and the current contribution policies remain, the system is not expected to run out of money. But it is very close.” (Italics added.) Worse still is how long the actuary says it will take to fully fund the system, given the same set of assumptions: never.

Pension Benefits

In FY 2010:

$925 million was paid by the plan to about 39,000 retirees and beneficiaries.