Hawaii is Business Heaven, Not Hell

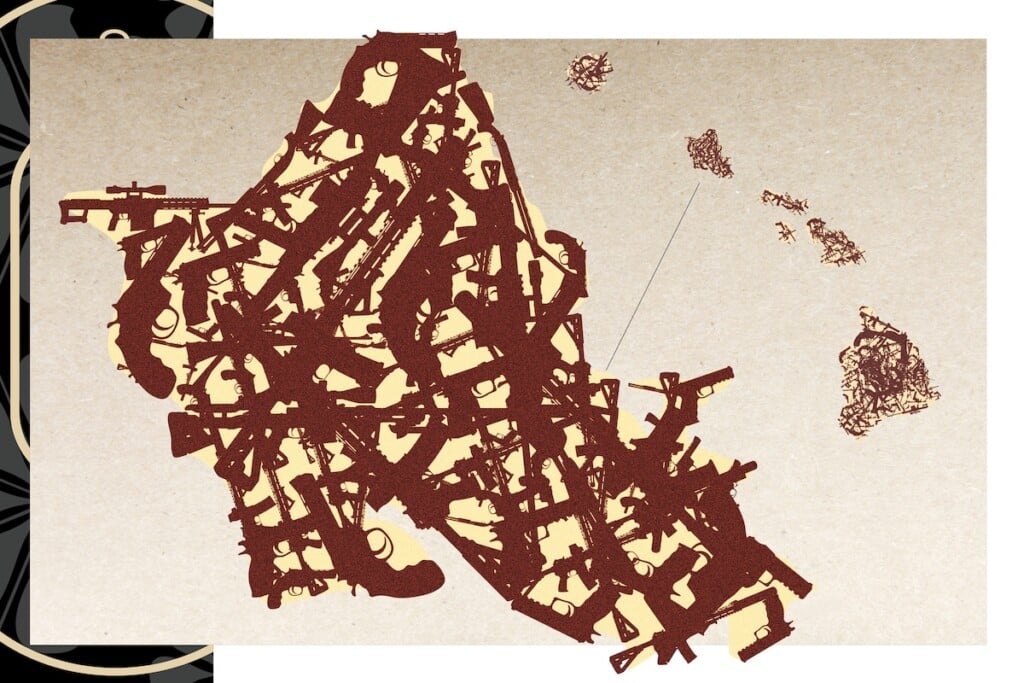

For many people around the world, Hawaii is paradise. They have a vision of pristine beaches, glorious sunsets and friendly people. In other words, heaven on earth.

But when it comes to commerce, the vision of Hawaii from the outside is more like those ghastly circles in Dante’s Inferno. Business hell.

This year, CNBC ranked Hawaii as the worst state for doing business after five years of ranking Hawaii either 48th or 49th in the nation.

The ranking evaluated 10 factors, such as the cost of doing business, economy, infrastructure and workforce.

A lot of local owners will nod their heads in agreement and also cite high taxes, onerous state and local government regulations, high costs and other challenges they face. But many other local business owners say all states provide their share of challenges and that managing a company in Hawaii is no more difficult than elsewhere in the country. Some even contend that their companies are thriving because they are in Hawaii, not in spite of it.

“My business has definitely benefitted by being in Honolulu,” says Patrick Sullivan, chairman and founder of Oceanit, a science and engineering company. Sullivan launched his firm in 1985, armed with a new doctorate in engineering from the University of Hawaii and just $100. The company got its start by accepting the odd engineering projects that bigger firms did not want to bother with.

The new kid on the block morphed into a powerhouse. Today, Oceanit has more than 160 employees, including an arsenal of elite scientific and engineering Ph.D.s from around the globe. It has raised more than $250 million in funding and spawned several successful spinoffs. The company has branch offices in Houston and Washington, D.C., as about 70 percent of its clients are based outside of Hawaii. Yet Sullivan would not dream of relocating, not to Silicon Valley or to anyplace else, because the conditions found in Hawaii are difficult to replicate.

“The environment in Hawaii – its community and culture – lends itself very nicely to innovative thinking,” he says. “We have many groups of diverse people that live together and work together and appreciate each other, which is critical because innovation comes from differences, not sameness.”

This dynamic plays a powerful role in creativity, he explains, while giving a tour of the company’s technology petting zoo. On display are cool inventions, such as paint that heals after being scratched or damaged. “It is like Wolverine,” says an enthusiastic Sullivan, referencing the Marvel Comics hero.

Plenty of Startups

There are many other entrepreneurs like Sullivan who are willing to double down their bets on Hawaii. The state has one of the highest business startup rates in the country, according to the Kauffman Index of Entrepreneurial Activity 2012. Hawaii’s rate was 400 per 100,000 adults, placing it eighth highest in the nation.

Some of those businesses have an international base of clients and investors and could relocate anywhere in the nation or even the world with minimal effort. Yet they vehemently stick with Hawaii for a host of powerful reasons, including its economy, workforce, special corporate initiatives and celebrated quality of life.

San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle. These were among the cities that did not make the cut when Kamakura Corp. was looking to relocate outside of Chigasaki, Japan.

At the time, the provider of risk-management software was already successful, but its location had hampered efforts to go global, recalls chairman and CEO Donald van Deventer. Seven years after its inception in 1990, the company was still struggling to expand beyond Japan and U.S. markets.

Before relocating, van Deventer connected with executives at large software groups on the mainland and heard the same chorus of complaints: Finding talent was difficult, keeping talent was nearly impossible. According to the Herman Group, an Austin-based workforce consultancy, the annual average rate of employee turnover in Silicon Valley is 25 percent.

It wouldn’t be feasible for Kamakura – a knowledge-based business whose value is intrinsic with its human capital – to operate under those conditions. The company needed a base where it would have access to a qualified workforce and not battle dysfunctional turnover.

Van Deventer zeroed in on Hawaii. “There is an unbelievable availability of talent here: mathematicians, computer scientists, highly trained economists,” he notes. “The best part is that they stay with employers for a long time.” Kamakura boasts a turnover rate of zero among its key software developers in the past 12 years.

Van Deventer attributes the stability in his company’s workforce in large part to being in Hawaii. “Nobody wants to leave,” he says. “The quality of life, the great schools and the ease of commute make it a good place to live.”

Hawaii has topped the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index for four consecutive years. The survey covers factors such as health and job satisfaction, and Hawaii’s residents report a greater incidence of overall well-being than other Americans. Even CNBC, which gave Hawaii its worst-in-the-nation ranking for doing business, places Hawaii at No. 1 in quality of life.

Workforce stability has benefitted Kamakura. “Turnover is extremely expensive and disruptive for knowledge-based businesses,” van Deventer notes. He calculates that the cost of replacing experienced software developers is a small fortune – as much as three times their annual compensation – partly because it can take years to get a developer completely versed in certain proprietary software.

According to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, the annual mean wage of software developers is around $87,000.

Relocating to Hawaii has played a critical role in Kamakura’s international push. Today, the company has clients in more than 30 countries and a strong global presence, including branch offices in Germany, the United Kingdom, Australia, India and Singapore. “For some reason, international clients were tentative to dial Tokyo,” van Deventer says. “They were nervous of what would happen when somebody picked up the phone on the other end.” This hesitation was embedded in language barriers, he explains, but Hawaii creates no such caller anxiety.

“I laugh when I see negative reports about Hawaii,” says Pono Shim, president and CEO at Enterprise Honolulu, a nonprofit that promotes business growth on Oahu. “Those companies that strive to succeed here do. Others use these studies as an excuse for why they failed.”

“Hawaii is where everybody wants to be,” he says, and he rattles off a list of national brands that have thrived in Hawaii: Sam’s Club, Costco, Dave and Buster’s and The Cheesecake Factory, to name a few.

Hawaii is a good place for any company seeking to expand its national and international footprint, says Stevette Santiago, senior VP at Hawaii USA Federal Credit Union and president of the Society for Human Resource Management, Hawaii Chapter. Hawaii offers strategic visibility, given the volume and diversity of its base of tourists. “It is a great springboard for all types of companies,” Santiago says.

Unique Fundamentals

Brandon LaBonte, president and CEO of the software development firmArdentMC, could have expanded his Washington, D.C., business into almost any area of the country. He opted for Maui.

ArdentMC has a Historically Underutilized Business Zone certification from the U.S. Small Business Administration. As such, the company receives federal contracting opportunities that benefit specially designated locations. There are HUBZone areas throughout the country, but none like Maui.

“HUBZones tend to be in areas that are economically challenged and in need of federal dollars,” LaBonte says. “The exception is the neighbor islands of Hawaii.”

Their HUBZone status has less to do with the economic climate and more to do with the high cost of housing. “It has the best of both worlds,” LaBonte says “Hawaii is a HUBZone, but it also has a stable economy with a well-educated workforce.”

LaBonte reviewed tons of maps and data and concluded that the fundamentals on Maui were one of a kind and too good to pass up. What the analysis did not indicate is that ArdentMC would also benefit immensely from a phenomenon that has no hard data: the famed Aloha spirit.

LaBonte remembers setting up shop and extending the first job offer. To his surprise, the recruit turned down the opportunity because he was uncertain about the longevity of ArdentMC in Maui. “It was demoralizing,” he recalls.

The disappointment was short lived, thanks in part to a shot in the arm from theMaui Economic Development Board. “They provided lots of support and Aloha spirit,” LaBonte notes. “They went above and beyond anything I had ever seen anywhere.”

He credits MEDB with helping with a range of tasks, from learning how to recruit more effectively to navigating through the permitting process. LaBonte urges all entrepreneurs, whether they are local or from the mainland, to seek this type of support. “It is invaluable and will make your life a lot easier.”

LaBonte is a big proponent of fostering community alliances in general. He tries to work with local companies whenever possible, whether construction companies, office suppliers or caterers. “Work with your local economic development group, work with other companies that are in the same field as you,” LaBonte says. “Tapping into your local network is a wise business move.”

ArdentMC has thrived since setting up on Maui. In just a couple of years, the company has hired about 33 high-tech employees and doubled its revenue. LaBonte says that the cost of labor is not higher on Maui than it is in D.C. “The difference is that in Washington, I’m competing for talent with big-brand companies, such as Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin,” he notes. “In Maui, we have more name recognition and more leverage to attract qualified employees.”

The company has landed several multiyear contracts with the federal government, ensuring its longevity locally. ArdentMC’s office is in expansion mode, having furniture installed for 15 additional workstations to accommodate expected growth. “We are here to stay,” LaBonte says. “Hawaii has been good for our business.”

Hawaii or Bust

When Philip Manly, CEO of Connect Imaging, set up his business in 1999, he had two objectives. First, he wanted to create software that could be used for medical imaging that was functional, easy to use and not very expensive. Most important, Manly wanted to remain rooted in Hawaii.

“You want to be here, that is the given. Now what do you do to make it work? Do you sit around and complain? No,” he says. It took some thinking outside of the box, but Manly achieved his goals.

He structured Connect Imaging so that software development takes place in his Aina Haina offices overlooking the ocean. Other functions, such as assembly, testing and installation are handled in Pittsburgh. Technical support is also anchored on the mainland, which helps because most of the company’s clients are outside of Hawaii. By configuring his business this way, Manly does not have to worry about distance or time zones when providing services to clients.

Manly spends the same on monthly rent for his 800-square-foot office in Hawaii as he does for a 2,000-square-foot facility in western Pennsylvania. It is worth every penny, he says.

Moving to the Islands was a choice that the Ohio-born Manly made after earning his graduate degree in 1971. He weighed two job offers – one in Pittsburgh and the other in Hawaii. “The East Coast is nice, but in the winter time, the world becomes black and white. There is no color,” he recalls. “It can be depressing to be there.” He does not regret his decision.

Manly has excelled as an entrepreneur and his company has been repeatedly recognized as one of the state’s fastest growing. Not surprisingly, Manly believes that having a company in Hawaii is no more burdensome than having one on the mainland. If anything, Hawaii had initiatives that benefitted his business, such as the state’s Act 221, which provided tax credits to spur investment in tech companies.

Dennis Ling, administrator at the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism, says Hawaii has a portfolio of initiatives, grants and tax breaks designed to spur growth beyond tourism. Ling says that has helped create many successful companies, especially in the areas of renewable energy and technology.

DBEDT points to other positive factors for Hawaii. The state was not hurt as badly by the recession as most other states, and DBEDT projects that Hawaii’s economy will grow 2.9 percent in 2013 – exceeding the national average of 2.5 percent. Disposable income is stable and Hawaii’s unemployment rate was 4.3 percent in August, much lower than the national rate of 7.3 percent.

Manly says that being in Hawaii creates many possibilities that go beyond financial rewards. “Because we were here, the state passed some of the most comprehensive rules regarding radiation regulation. These are rules that are now being suggested to other states,” says Manly. “Being able to effect change in the radiation protection environment has been incredibly rewarding.”

Manly concedes that Hawaii has geographic challenges. But the self-confirmed golf aficionado wouldn’t want it any other way because it is part of the fabric of Hawaii. “People want to be here,” Manly says. “Larry Ellison didn’t buy South Carolina. He bought the island of Lanai.”

Dispelling Misperceptions

Whether hobnobbing in Washington with Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid or addressing business executives in Tokyo, Sherry Menor-McNamara makes one thing clear: Hawaii is more than just a pretty place. “We want you to come not just on vacation, we want you to come and do business with us,” says the president and CEO of the Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii.

Menor-McNamara knows that reports often rank Hawaii poorly as a place to do business, but she says the chamber is trying to change that dynamic. One step is to conduct research and interview its members to identify potential hurdles that could hamper business activity. “Research is important to get the full picture,” she says.

The chamber is also making an unprecedented move to promote the interests of the business community by bringing a cluster of bills – a business package – to the state Legislature for the upcoming session. “Traditionally we have played a game of defense, blocking moves that would be detrimental to the business community,” Menor-McNamara says, “but this time we are willing to play more offensively because the stakes are high.”