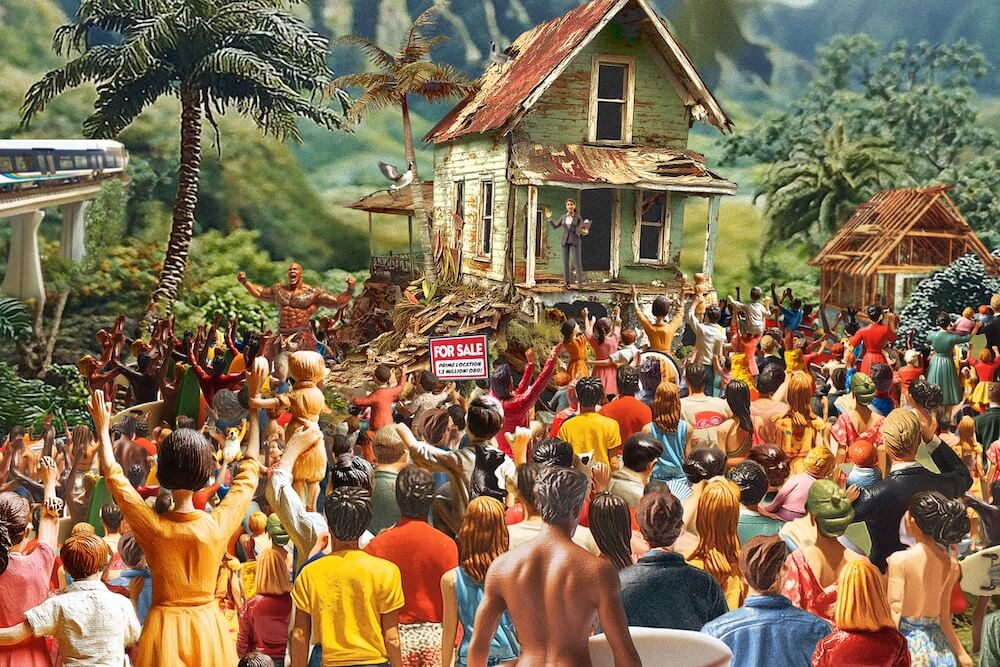

Hunting for a New Place in Renters Purgatory

How four O‘ahu residents navigate fees, scams, unanswered calls, intrusive rules and housing options that run from “crappy and crappier.”

After his father died in March, UH Mānoa librarian Ben Dias searched for a new place to live. He used social media, Craigslist, Zillow and other online apps to hunt for a place, but a divorce hurt his credit score, making it difficult to even get an appointment to apply for a rental.

Using online search engines, he says he would input “one to two bedrooms and the price range and in town and then the amenities that I wanted: with parking, washer/dryer on property. And then as I put those in, the search (results) went down narrower and narrower.”

The National Low Income Housing Coalition says 38% of households in Hawai‘i are composed of renters, the fourth-highest percentage in the nation. The study also says the individual income needed to afford a single-bedroom home in Hawai‘i is $71,185, compared with the national average of $41,850, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

UHERO, UH’s Economic Research Organization, says Hawai‘i has the highest average rent in the nation: $2,000 a month.

The Place Has to Be Safe

Dias was looking for a one- or two-bedroom apartment in town, which he defined as Moanalua to Kaimukī, with a rent of $1,700 to $2,000 a month. Security was crucial for the safety of his 8-yearold daughter.

“If I had to go do the laundry, I didn’t want her to be harassed by any strangers or anything,” he says. “Security entrance, washer/dryer on-site – doesn’t have to be in the unit but had to be on-site.”

Luckily he found a place after getting a referral from the property management company that his mother uses to rent her apartment.

“I have no problem paying my bills,” he says. “It’s just that I couldn’t show that I had credit yet because I had recently got divorced, and it was in our joint.”

Once he started working with the property management company, he found a place faster than expected.

“Renters are kind of shocked at the sticker price of rentals in town,” he says. After a four-month search, he found a one-bedroom apartment for $1,800 a month, which covers rent, amenities and taxes.

More Than Just Rent

Dias’ apartment was listed at $1,600 a month but additional costs for insurance, fees and taxes were written into his contract, raising the monthly total by $200. That kind of rental pricing is becoming more common in Hawai‘i.

Grassroot Institute of Hawaii VP Joe Kent wouldn’t be surprised if rents for apartments increase in 2025 since the cost of maintaining and repairing aging condos is often passed from owners to renters.

“This is a really complicated issue … but basically, there are all these old buildings that have not been maintained, and the costs for that are going to be shifted on to renters in the future,” Kent says.

Many condominiums in Hawai‘i were built in the 1960s and ’70s, and homeowner associations frequently kept fees low through the decades. Because of that, condo associations didn’t build enough reserves to cover inevitable – and expensive – maintenance and repairs to pipes, elevators, balconies and other infrastructure.

“Now, it’s to the point where these buildings are so poorly maintained that insurance companies are constantly having to pay for broken water [pipes] leaking down 20 floors from the top floor pool, which is really expensive,” Kent explains. So either repairs must be made, he says, or the price of insurance goes through the roof.

Kent predicts tenants will see an increase in rents but reminds them that they can fight back.

“If you’re a renter, remember that your biggest bargaining chip is the ability to search for a different apartment,” he says. “Owners can only set the price that renters will pay.”

Kent recommends that when looking for a place to rent, ask about the infrastructure to see if there will be any plumbing or other problems that could result in future rent increases.

A Time-Consuming Burden

A scroll through apartment listings is an everyday routine for 33-year-old Savvy Coules, sister of Hawaii Business Staff Writer Ryann Coules and daughter of Co-Publisher Kent Coules.

“I look at apartments probably almost every day on Zillow, and I’ve toured more than a few in the last few months,” she says.

Zillow, a real estate marketplace, shows how long listings have been up and how many contacts have been made, which adds another competitive element to the rental hunt.

“You have to be so aggressive and try to see the place early, meeting potentially the property manager trying to sell yourself to them,” she says. On the other hand, sometimes she tries to contact the lister but no one gets back to her.

Coules says she now exclusively looks through Zillow but has used Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace in the past. She says the latter two websites have included scams with too-good-to-be-true listings, and that some have tried to lure prospective renters into sending deposits with the promise that keys will be sent in return.

Other listings “give you weird lifestyle demands, like no visitors, no overnight guests,” she says. “I’m paying rent. I don’t really know what that has to do with you.”

Listings can possess a unique set of requirements: application fees, credit scores, bank statements, paycheck stubs. Application fees are not regulated in Hawai‘i so sometimes the landlord is using the application fee to screen the tenant.

As of May 2024, Hawai‘i landlords cannot charge a screening fee that is more than the actual cost for an applicant to get the same information. The typical cost for screening can run from $25 to $100.

“I feel like it’s a scam, especially when they say there’s an application fee for every single adult who’s going to be in the house,” she says, adding that those fees add up when applying for apartment after apartment.

“And for people who are funneling so much money, they’re freaking out. They’re so stressed already, having thrown this much money at application fees.”

Coules says that studios listed online for $1,500 to $1,800 often lack full-size appliances or even kitchen space. For those, and some other higher-priced rentals, she says she wants to ask the property owners, “Are you out of your mind trying to charge people that much for that?”

And sometimes, when a prospective renter finds a more affordable rental, it turns out to be not very nice. “I guess you’re getting what you pay for,” Coules says.

Like Dias, she notices units advertised for one price, but then finds out about add-ons like $100 for parking and a $150 base rate for electricity.

Rising Costs, but Not Quality

Arjuna Heim, director of housing policy for the Hawai‘i Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice, says Hawai‘i isn’t building enough housing – and that leads to high rental prices. She says all the studies point to that explanation.

Coules has a place to live but she’s not happy with it. However, all of the alternatives she’s found since moving in would be “like a lateral move for me,” she says. “Why move out of my place to go live somewhere just as crappy or crappier?”

With no imminent pressure to move and a flexible remote work schedule, she can look at homes during the day – an option not available to all home hunters. Listings will often include details about open houses on specific days, saying, “Come if you can.” She says, “I feel like it’s so rare you find a dream apartment here, though.”

Coules says she wants to find something better than her current one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment; she’s been living there since December 2020 for $1,300 a month.

“It checked all my boxes at the time. I wanted air conditioning, I wanted a one-bedroom. I wanted parking, and it was in a pretty convenient location, right off McCully.” Everything went well for years except for a cockroach infestation that ended with Coules having to pay exterminator fees.

Then in January, her landlord informed her that he was raising the rent $100, effective in March. That was reasonable, she says, but then, “for the first time ever, I saw a rat in my apartment.”

“I was like, ‘You need to fix this,’ ” she says. But instead of fixing it, the landlord advised her to buy traps. “I had to call the Department of Health, and they basically told him, ‘It’s not a tenant problem.’ ”

After she lived with the rats for six months, her landlord hired an extermination company and Coules says she hasn’t seen a rat since. Her lease isn’t up until March 2025, but after the infestations, her landlord offered to let her move out early.

But her apartment hunt has been fruitless. “I feel like there’s always at least one thing that’s just not going to work for me, and it’ll be something that I think most young professionals, at the very least, are going to want. I need laundry on-site,” she says. “I don’t need a giant full-size kitchen, but I want” a refrigerator, stove, oven, sink, parking and air conditioning.

And no rats.

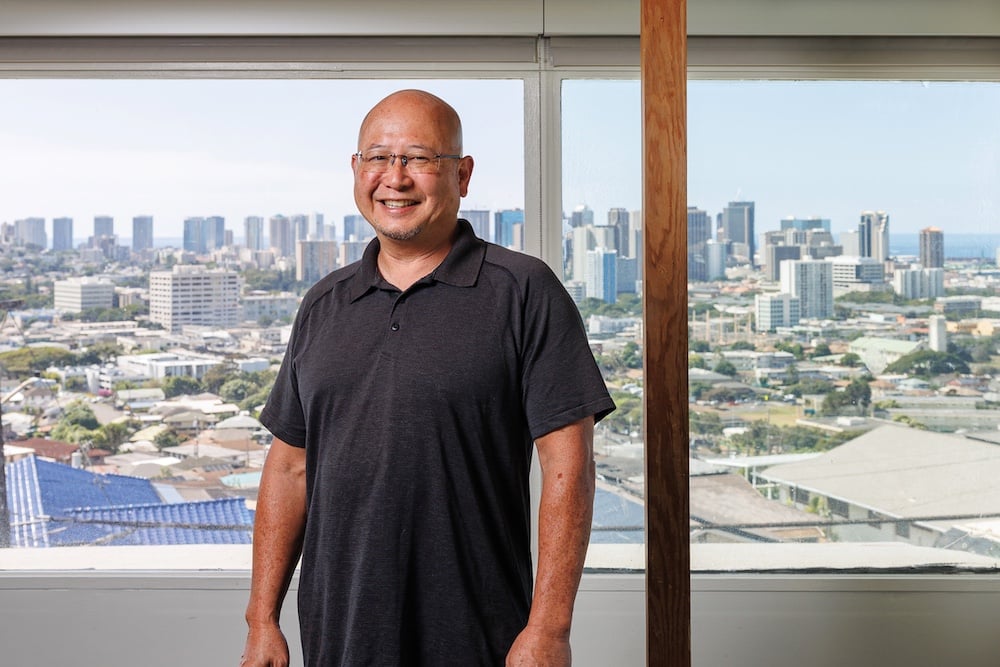

Beyond the Internet

Since moving to Hawai‘i in 2017, Chris Abarca, 31, has rented places in Waipahu, ‘Aiea, Windward O‘ahu and Honolulu.

“I’ve lived on pretty much every corner of the island but North Shore, and it has been impossible to find a rental” through apps and online listings alone, he says. “And I think the only reason I was able to do it was just because I happen to know somebody who was looking for a roommate, or someone who knew that there was a spot opening for their landlord, or in their unit.”

Renting from a person, not a company, allowed Abarca to connect with the landlords, which he says allowed him to feel like “more than just a wallet.” When he was looking online, he found that the apartments were overpriced and the criteria to book viewing time was extensive.

“I’m filtering through the price range, and like, I’m seeing not even a bedroom, but a bed. Like people are renting out their beds in a room,” he says, adding he was lucky if he found a place that met his needs once every three weeks.

So he and his partner, Louise, instead started searching for a condo to buy, deciding it was cheaper in the long term and eliminated their dependence on landlords and their rules. “Renting and staying here long-term isn’t feasible. It’s just that you can’t really live comfortably or get by, unless we were going to be housemates with other people.”

SmartAsset, an online platform that provides information to help people with their personal finances, reported in March 2024 that individuals in Hawai‘i need to earn at least $111,904 annually to live comfortably. The national average is $96,500. The study assumes that no more than 50% of income is spent on housing, groceries and other necessities, while 30% goes to entertainment and hobbies, and 20% pays debt or goes into savings and investments.

Abarca is a senior digital creative manager at Longs Drugs and also freelances in design and marketing. He and his partner together can earn about $110,000 annually, depending on his freelance work. They purchased a studio in the McCully area in January. The monthly payment is $1,500: $500 for homeowners association fees and $1,000 for the mortgage. The monthly total for renters in their complex is $1,800 or more, Abarca says.

He says the move into a condo only happened because he worked with a real estate agent and his partner had a financial advisor. Those two connections helped the pair work directly with representatives to help them get a mortgage and move forward with the purchase.

“It does require a team,” Abarca says. “It’s like a small team, because without us having the credit, without the help of the real estate agent and the financial advisor, I don’t know how we would have been able to do it.”

Housing Man’s Best Friend

Everyone I interviewed mentioned the struggle of finding a pet-friendly rental.

“It’s a lot harder to find pet friendly buildings now,” says Dias, the UH librarian. “When I was younger, everybody’s like, ‘I don’t care if you have a dog. Just pay the deposit fee.’ ”

The pet deposit – designed to cover damage caused by the pet – used to be just $50 to $100 as long as the place was maintained properly. If it was, the renter would receive the deposit back at the end of the tenancy. However, he says, in the last three places he rented, the owners requested “an exorbitant amount of money for a pet deposit.”

Dias doesn’t currently own a pet but had been looking for a dog since his daughter asked for one. That search ended with the “no pets allowed” clause in his rental contract.

Abarca’s first studio rental with his partner didn’t allow pets at first, but as they and their landlord got to know each other, the landlord eventually allowed it.

In their latest search, Abarca and his partner made pet-friendly locations a priority and found a condo that allowed their dog and cat.

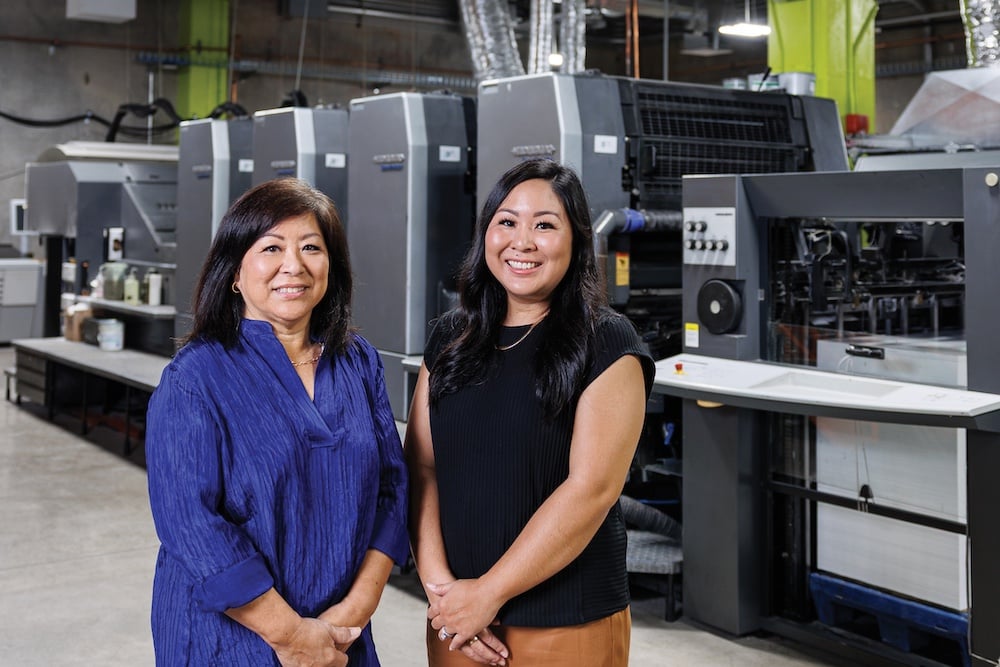

Renting Alone in Your 20s

Vanessa Hathaway, then 19, looked high and low for a place close to UH Mānoa that aligned with her college student budget.

“I was just scrambling, trying to find any kind of rental that’s cheap, and most of it was in Waikīkī, which is kind of scary if you’re living by yourself as a woman,” she says.

Through Craigslist, a platform she calls “suspicious,” she found her current room in a shared home. “You definitely have to make sure you’re not talking to a psycho,” she says of the platform.

Now she is 22 and working as an associate editor at Trade Media Hui, her first full-time job. And she’s searching again for a rental, this time for a place where she can live on her own. For rent, she says she can afford to spend $800 a month.

“The cheapest (studio) I saw was maybe like $1,100 or $1,200 and that’s still way more than I’m paying right now, and I’m trying to keep my rent 30% of my income,” she says.

“I don’t need parking, AC, anything like that. But even with those really low standards, it’s still really expensive.”

She finds herself scrolling on Zillow to see what is available. “I do it for fun, once in a while. But unless I find a crazy good deal, I’m going to have to get promoted before I look for a new place.”

Justin Tyndall is an associate professor at UH Mānoa and a member of UHERO, the UH Eco-nomic Research Organization. He says 56% of households in Hawai‘i are rent-burdened – meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on rent.

“Nationally, 47% of renters spend more than 30% of their income on rent. And in Hawai‘i, it’s 56%, so a little bit higher,” he says. However, to buy a home in Hawai‘i, “we’re way out of the norm. It’s obscenely expensive and unaffordable to get a mortgage on a typical house.”

A Lifelong Renter

Dias has been a renter since he was 18, when he first moved out of his parents’ house. “I’ve always rented,” he says. “I knew I was never going to be able to buy.”

Now 50, and an O‘ahu renter for 32 years, he says the search for a rental has gotten much harder: Pay has not kept pace with increases in rent and food prices.

A down payment on a condo is beyond his reach, Dias says. “I’ll probably be paying rent forever. I don’t think I’ll ever own my property anywhere in Hawai‘i.”

A decade ago, when he was still with his wife, he tried to purchase a home through the federal Affordable Housing Act. But finding an affordable unit, he says, was like a lottery.

“I’ve sat in the lottery, I’ve stood in the lines, been on the lottery list, and we’ve never won,” he says. “My ex-wife and I were definitely trying to get a place together, and so we were trying to apply at all these places, trying to save our money and scrape and this and that.”

He and his ex-wife, who are jointly raising a daughter, now rent separate apartments.

“Until her parents die, or my parents die, I don’t think we’re going to be able to own a place,” he says. “And even then, my dad has passed away, and I have a brother and two sisters, so the money has to be split four ways. I’m not depending on that money.”

Dias is focused on his daughter’s future and saving for retirement. While the thought of leaving the Islands has crossed his mind, he is committed to staying and helping raise her.

“As long as my daughter’s here, and she needs her dad, I’m not going to leave. Once she’s 18, I might think about it, which is 10 years from now.” Then, he says, he might move to Las Vegas or Oregon.