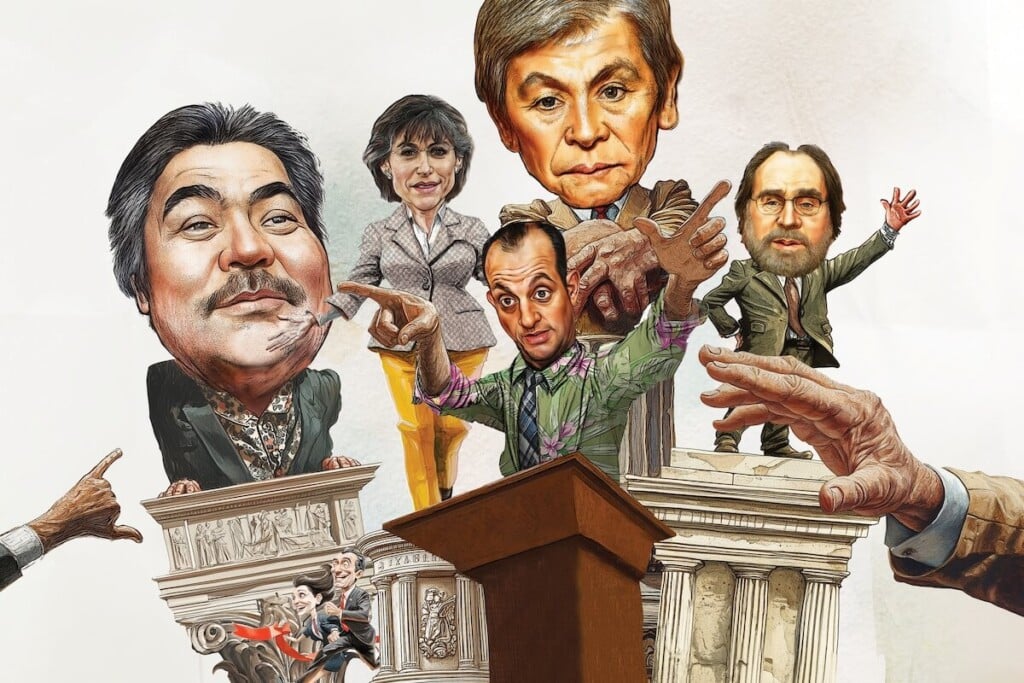

Hawaii Business Environmental Report: Pesticides

Critics say use of the chemicals by seed companies endangers the health of Hawaii’s people, but the companies insist they are using pesticides safely and following federal regulations. A recent report suggests a way forward on the issue.

Malia Chun was elated when she was selected for a Department of Hawaiian Homelands homestead on land surrounded by fallow sugar fields on the west side of Kauai about seven years ago. “I’m a single mom, so it was the only way I could afford my own home,” she recalls.

Not long after, she noticed corn sprouting up in nearby fields and her family began suffering health problems. She says they developed recurring respiratory infections and couldn’t seem to ever get well, even though they had always been healthy before.

“THERE’S NO QUESTION THAT EXPERIMENTAL FIELDS USE MASSIVE AMOUNTS. IT’S ALMOST UNPRECEDENTED.”

-DR. LORRIN PANG, MAUI DISTRICT HEALTH OFFICER, STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

“On certain nights, my daughters would wake up with burning eyes, burning throats,” she says. “I had no idea what was going on.”

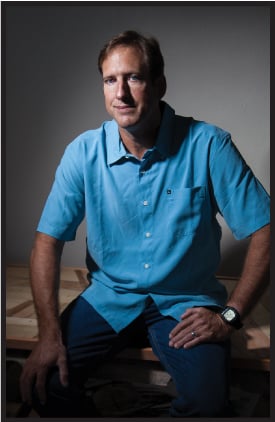

Photo: Mike Coots

After two years, Chun was diagnosed with adult asthma and her doctor said the cause was environmental. She says she began looking closer at what was happening just beyond her front door and realized the fields were being sprayed at night, while they slept.

“I was just wondering what was being sprayed around my house,” she says. “The more I learned, the more alarmed I got, and the more concerned as a mother I became.”

Pesticides have long played a major role in Hawaii agriculture and their health and environmental impacts are nothing new. Drinking-water wells in Kunia were closed in 1980 by the state Department of Health, and later declared an EPA Superfund site, after they were found to be contaminated with ethylene dibromide and dibromochloropropane (DBCP). A 1997 study by scientists at the National Cancer Institute found exposure to the pesticide heptachlor had likely contributed to rising breast cancer rates in Hawaii.

As agriculture in Hawaii has changed, so has pesticide use. Sugar-cane and pineapple fields were treated to stop weeds and hungry insects. Now many of those same fields are planted with pre-commercial seed crops, often new varieties of corn and soy that are being developed specifically to withstand stronger applications of pesticides.

With a few exceptions, the seed companies are not saying exactly which pesticides they use in Hawaii, are when, where and how much they use, and government regulations don’t require the release of that data. However, critics say the available information indicates these experimental crops are sprayed more frequently, in greater concentrations and with more toxic chemicals than Hawaii has seen in the past. These critics fear this intensification of pesticide use endangers the environment and human health.

“ON CERTAIN NIGHTS, MY DAUGHTERS WOULD WAKE UP WITH BURNING EYES, BURNING THROATS. I HAD NO IDEA WHAT WAS GOING ON.”

-MALIA CHUN

Small farmers and residential users also apply pesticides, but they aren’t driving the chemical boom, says the state Department of Health’s Maui District health officer, Dr. Lorrin Pang. “Without a doubt, it’s the corporate guys who are growing genetically modified crops,” he says. “There’s no question that experimental fields use massive amounts. It’s almost unprecedented.”

Pang is especially concerned about the combinations of chemicals being applied by seed companies, noting that some field trial reports show that some mixtures being tested contain up to 85 different pesticides. Pesticides can also mix when they are applied at separate times in the same field. Even if all the pesticides have been approved for use individually by the EPA, it’s common knowledge in the medical community that chemicals can have a different effect on the human body when they are combined, he notes.

Cases of acute exposure, such as schools being evacuated after children report symptoms, may get the most attention, but Pang is more concerned about the effects of small doses over the long term, “where it’s slowly hurting you, and it was so slow, you don’t realize it.”

“THERE ARE NO EXPERIMENTS WITH PESTICIDES IN HAWAII.”

-KIRBY KESTER, PRESIDENT, HAWAII CROP IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION

Photo: Rene Kester

State Department of Agriculture chairman Scott Enright did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Shay Sunderland, Kunia Site and Hawaii Technical Outreach Lead for Monsanto, took issue with the characterization that seed companies are using more chemicals than farms of the past. Improvements in pesticides over the last generation, as well as an increase in the use of integrated pest management techniques, such as rotating crops, have meant that applications can be more focused, he says. “The modern pesticides are used at much lower rates and with much more precision than the older chemistries of 20 or 30 years ago,” he says.

While not every possible combination of chemicals has been tested by the EPA, commercial pesticide mixtures that have been approved for market use have been extensively reviewed, he adds. Restricted use pesticides also come with strict labeling requirements detailing where and how they can be sprayed, he says. “If you’re not using it according to the label, you’re breaking the law.”

Most testing of new herbicides is done in Mainland laboratories, but if the pesticide being sprayed on a farm here is one that’s still in development, that’s also done under the oversight of the EPA, he notes. “There’s no instance where somebody’s going to take some chemicals and come up with something new and go out and start spraying it,” he says. “There’s assessments and safety protocols before (use in the field) is even allowed.”

While the seed industry first put down roots on Molokai in the 1960s, the legalization of plant patenting and breakthroughs in genetic engineering helped trigger the industry’s rapid expansion in the Islands during the 1980s and 1990s. Hawaii’s year-round growing season makes it an attractive place to develop new varieties of corn, soy and other commodity crops, since it often takes a dozen or more generations to make a new hybrid plant ready for commercial distribution.

“If you did that in the Midwest, it would take 15 years, but in Hawaii it can take five years,” says Kirby Kester, president of the Hawaii Crop Improvement Association, a trade association for the seed industry.

Today, Monsanto, Syngenta, DuPont-Pioneer, Dow Chemical and BASF – five of the six biggest international agrochemical companies – operate on farmland in Hawaii. Around 24,700 acres are devoted to the seed industry statewide, with corn and soy making up more than 90 percent of the crops being tested, according to the report “Pesticides in Paradise,” released in 2015 by the advocacy group Hawaii Center for Food Safety, a major foe of the seed companies operating locally.

Since 1987, the USDA has issued more than 3,240 permits for field tests of genetically engineered crops in Hawaii, more than any other state. The report says that, because of Hawaii’s small size, those test fields are denser and closer together than in other parts of the country, and tend to be nearer to residential areas.

“THE HERBICIDE IS ONLY USED ONCE IN THE LIFE OF THE PLANT.”

-JILL COOMBS, FIELD RESEARCH BIOLOGIST ON MOLOKAI, DOW CHEMICAL

While genetic engineering might hold the promise of feeding the world into the future with drought-resistant crops and more nutrient-rich grains, that doesn’t appear to be the focus of work being done here, notes Ashley Lukens, executive director of Hawaii Center for Food Safety.

USDA records show that, over the past five years, 68 percent of the 802 field releases of genetically modified crops in Hawaii were to test crops for traits of herbicide tolerance, according to the Pesticides in Paradise report. That percentage increased to 82 percent in 2013 and 2014, the report says.

“It’s really clear that what they’re doing in Hawaii is engineering corn and soy to withstand increasing amounts of pesticides,” says Lukens. “None of the products that the industry grows here end up in grocery stores, or even being sold to farmers. They’re experimental.”

THE SEED CHAIN

Dow employees gather plant tissue samples for trait screening at the company’s farm on Molokai.

That’s a characterization Kester takes issue with. “There are no experiments with pesticides in Hawaii,” he says flatly. Rather, hybrid and genetically engineered seeds are screened here during the propagation process, to ensure they still have the traits for which they were developed in the lab.

Understanding where Hawaii fits in the chain of development for new seeds might help explain that distinction.

When an agrochemical company wants to develop a new type of seed, the actual process of genetic engineering takes place in a laboratory on the Mainland. If a plant is being developed for herbicide resistance, testing on those first experimental seedlings will occur in a laboratory greenhouse.

Once the company has a seed it wants to take to the next stage, that seed is shipped to Hawaii. Here, it’s cross-bred with other plants over many generations of crops, to combine the genetically engineered trait (for example, herbicide tolerance) with complementary qualities, like hardiness or high yield, that already exist in established varieties of the seed.

Sometimes during this process, the genetically engineered trait will disappear after cross breeding, Kester notes. To prevent the trait from dropping out of the new strain entirely, seed companies test the plants in each generation, and remove any plants that no longer show the trait. For seeds being developed for tolerance to a specific herbicide or combination of herbicides, that means spraying the plants with those chemicals, and removing any seedlings that show an adverse reaction, he says.

As a field research biologist for Dow Chemical on Molokai, Jill Coombs has supervised many such field trials. She says the image of agricultural research companies drenching fields in toxic chemicals over and over again is a misconception. Instead, in the trials she’s worked on, each plant was sprayed once with the herbicide when it was about two weeks old. “The herbicide is only used once in the life of the plant,” she says. “It’s really just to test if the gene is present or not present.”

Coombs says her company has three or four licensed applicators who are trained in the use of pesticides, and they are the only ones who touch those chemicals, she says.

She also notes that, on Molokai, Dow takes other precautions to control its pesticide and chemical use. The company uses integrated pest-management practices, such as rotating fields, to reduce the need for chemical intervention against bugs and weeds. When a field is sprayed, employees work in another part of the farm. And test fields are spread far apart, both to ensure gene purity and to prevent pesticide drift. Out of Dow’s 400 acres on Molokai, Coombs estimates the company conducts field trials on only around 15 acres each year.

Coombs estimates she supervises around 300 field trials each year, but each test covers an area only about 60 yards long by 10 yards across. “We do grow a lot of fields every year, but our trials are tiny – none of them is bigger than an acre,” she says.

There’s one other role Hawaii plays in the development of new seeds, Kester notes. Once a new variety has gone through many generations, and the company has decided it is ready for the marketplace, local farms will plant larger and larger fields, “ramping up” the output to create a larger volume of seeds that will be sent to the Mainland to be put into production for commercial distribution.

Hawaii’s role in the chain of development of a new seed is vital for these international agribusinesses. Coombs says one thing she finds most exciting about her job is knowing that every new strain of corn Dow creates for sale to farmers – including varieties developed for Brazil, Canada, the Midwest, and Texas – makes a stop on Molokai.

“The rewarding part of my job is that we’re such a small farm in such a small area, but we contribute so much to agriculture around the world,” she says

DATA LACKING

While industry leaders offer assurances that pesticide use in Hawaii is conservative and controlled, actual data is scarce on what chemicals are being applied, where, when and in what amounts, Lukens notes. Instead, the public can only deduce that information from the limited disclosures that are available.

Those sources include field trial reports filed with the USDA. These reports don’t say how pesticides are used, but they do disclose the traits being tested in the plants – including the type or types of herbicide they are designed to withstand. From this, outside observers can infer what chemicals are likely being sprayed. “We get what pesticide, but we don’t get how much,” Lukens says.

Photo: Aaron Yoshino

The state government requires the disclosure of annual sales of restricted-use pesticides – chemicals that aren’t available to the general public, and which can only be used by a certified pesticide applicator. Even here, data is limited. “You don’t know what restricted use pesticides are being sold, and you don’t know who’s buying them, where they’re using them, and what they’re being used for,” Lukens notes.

When it pressed the state for more information, Hawaii Center for Food Safety says it was able to get a breakdown of the sales data by large and small users, which revealed the significant majority of restricted-use pesticides sold in Hawaii were purchased by large businesses.

A third source of data was revealed in the course of a lawsuit against DuPont-Pioneer on Kauai. Records released as a result of the suit give a snapshot of how one company on one island uses pesticides.

They showed that DuPont sprayed pesticides on 65 out of every 100 days over a six-year period, making 8.3 to 16 pesticide applications per spraying day. The third-most frequently applied type of pesticide was in the organophosphate class, a type of chemical linked to neurological development issues and respiratory problems in children, Lukens notes. These types of pesticides were sprayed an average of 91 days each year.

The data point to a heavy amount of spraying on Kauai, especially if other companies are applying chemicals at similar rates, says the Center for Food Safety report. “Even if one accounts for the fact that applications are made to only portions of the companies’ overall seed fields, this still represents extremely intensive pesticide use,” states the report.

On Kauai, seed companies also disclose some information about their pesticide use through the island’s “Good Neighbor Program.” Under the program, agrochemical companies voluntarily notify schools, hospitals and medical clinics before they spray nearby, and provide monthly reporting of restricted-use pesticide applications to the state Department of Agriculture.

“YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT RESTRICTED USE PESTICIDES ARE BING SOLD, AND YOU DON’T KNOW WHO’S BUYING THEM, HWERE THEY’RE USING THEM, AND WHAT THEY’RE BEING USED FOR.”

-ASHLEY LUKENS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, HAWAII CENTER FOR FOOD SAFETY

Lukens says the program provides an important glimpse into the pesticide use in one community, but notes, “It’s voluntary, so there’s no legal lever to determine if this is accurate data.”

While advocacy groups call for more disclosure of how pesticides are being used, there are also “clear data gaps” on how those pesticides are showing up in our environment, says Fenix Grange, an environmental toxicologist with the state Department of Health. While other states have regular surface water testing and other programs to monitor the presence of pesticides in the air and water, Hawaii does not, Grange says.

“A lot of the fear I see in the community is because we don’t have data,” she says.

Gathering and sharing that data, and using the information to identify specific problems and fix them, could go a long way toward developing public trust around the issue, she says.

“NO OTHER STATE HAS THE INTENSITY OF (PESTICIDE) USE THAT WE HAVE. WE USE MORE, AND IN MORE CONCENTRATED QUANTITIES THAN ANY OTHER STATE, AND WE HAVE GROWING SEASONS THAT GREATLY OUTSTRIP ANY ON THE MAINLAND.”

-JOSH GREEN, PHYSICIAN AND STATE SENATOR

While previous studies did not find alarming levels of pesticides in the environment, Grange noted they only provided a “snapshot.” Many pesticides are only detectable in surface water for a short time after application. To identify areas where pesticides are leaving the field and getting into the environment in excessive amounts, more frequent air and water monitoring would help, she says.

State Sen. Josh Green, a physician who has advocated for increased regulation of pesticides, says the available data is concerning. Hawaii is “completely unique” in its relationship with pesticides, he says. “No other state has the intensity of use that we have,” he says. “We use more, and in more concentrated quantities than any other state, and we have growing seasons that greatly outstrip any on the Mainland.”

While the seed industry and its supporters contend that the chemicals they use are already regulated by the EPA, Green is among those who believe federal regulations are far from adequate.

He and others note that EPA regulations on restricted use pesticides only account for the health risks of chemicals used individually, not in combination; and USDA regulations on seed trials require only that crop species, intended trait and field-test locations be reported. The last environmental assessment of a field test on genetically engineered crops in Hawaii was in 1994, and there are no restrictions on how close companies can spray to schools, hospitals and homes.

“They’re not protecting people, and they move too slowly,” Green says. “It might not be a big issue if you’re in Montana and there’s very little spraying here or there, but if you’re on a tropical island with very dense spraying and large seed trials, you should be more careful, not less.”

That’s in line with the conclusions presented in a draft report on Kauai pesticide use released in March by a joint fact-finding group that included doctors, independent scientists and seed-company representatives. While the panel found no evidence that pesticides were causing harm, the members also noted that not enough information was available to carefully assess pesticide use or pesticides’ health and environmental impacts.

A top recommendation of the report was to improve agricultural, environmental and health data collection, including establishing regular sampling of water, air, soil and dust. The committee also calls for a major update of Hawaii’s pesticide laws and regulations; an expansion of the Good Neighbor Program; and other changes, including establishing buffer-zone policies, adding pesticide inspectors and establishing a user fee on pesticide sales. The report recommended earmarking an additional $3 million in state funds for the improvements.

Concerns about her family’s health inspired Chun to activism. After initially being rebuffed when she reached out to neighbors with her concerns, she became involved in Kauai’s anti-GMO movement. “I didn’t feel alone anymore,” she says. “I met other moms who were just as concerned.”

The fields near her home are now fallow, and her family’s health seems to have improved, although she still experiences occasional asthma attacks. She now votes with her dollars by boycotting products from companies whose research practices she opposes. She and her daughters have started growing greens, taro, sweet potato, bananas, papayas and other produce on their homestead. “It was an awakening,” she says.

For Lukens, Chun’s story illustrates the class issue raised by pesticide exposure in Hawaii. It’s significant, Lukens notes, that it’s been places like rural Kauai where the debate has been focused, and where pesticides continue to be prevalent even after apparent exposure at local schools.

“If Punahou was evacuated for pesticide drift? No way” would it continue, Lukens says. “It’s only because this is happening in low-income communities of color that there’s even a conversation about it.”

Digging Into the Issue

Among the recommendations in a draft report released by a pesticide fact-finding group are updating Hawaii’s pesticide laws, and budgeting $3 million in state funds to implement new regulations and management practices. The report, by an independent group of Kauai citizens convened by Kauai County and state Department of Health, was released in March.

Other key recommendations include:

- Set state standards for chronic, low-level exposures to pesticides.

- Expand Kauai’s Good Neighbor Program, which provides voluntary reporting of pesticide use and local notification before pesticides are sprayed.

- Establish a consistent policy for buffer zones.

- Establish systematic sampling and monitoring programs to detect pesticides in surface water, near-shore waters, air, soil and dust.

- Monitor air quality near Kauai schools, offer voluntary blood and urine tests, and provide mandatory pesticide education for students and families.

- Test for the pesticide chlorpyrifos in Kauai’s drinking water systems.

The fact-finding panel’s eight Kauai members are: UH Sea Grant Kauai extension specialist Adam Asquith; pediatrician Dr. Lee Evslin; Gerardo Rojas Garcia, Kauai R&D site leader for Dow AgroSciences; Sarah Styan, senior research manager for global market technologies at DuPont Pioneer’s Waimea Research Station; planning and land-use expert Kathleen West-Hurd; retired surgeon Dr. Douglas Wilmore; Limahuli Garden and Preserve director Kawika Winter; and organic farmer and independent organic inspector Louisa Wooton.

The draft report can be found online at www.accord3.com/pg1000.cfm.