Hawaii Architects Make Order Out of Chaos

Three award-winning local architects talk about their roles in society, preserving historical buildings, and the ugliest and best-looking buildings in town.

Glenn Mason and Bettina Mehnert were selected in April as fellows in the American Institute of Architecture, one of the most prestigious honors in the profession. Only about 3 percent of AIA members are fellows. Hawaii Business senior writer Dennis Hollier asked them and Daniel Friedman, also an AIA fellow, about the state of architecture in the Islands. Here is an edited version of that conversation.

Bettina Mehnert’s firm, Architects Hawaii, designed the new Walgreens store at Kapiolani Boulevard and Keeaumoku Street. Photo: David Croxford

The Importance of Architects

PHOTO: DAVID CROXFORD

“Architects are important because we shape the community: how it looks and feels. We don’t just design buildings; we create the spaces around them.” —Mehnert

Friedman: “If you ask me, as an educator, what I’m trying to instill in the imaginations of our students, it would be this principle: to protect the public from the trivialization of the constructive world. Architects are very different from builders, contractors, steel workers, plumbers and electricians, because we’re the only ones who take responsibility for the whole and the relationship between parts. When we talk about 3D-printing buildings, my concern is not the quality of construction, my concern is the monotony and mindlessness that’s possible out of mass producing anything.”

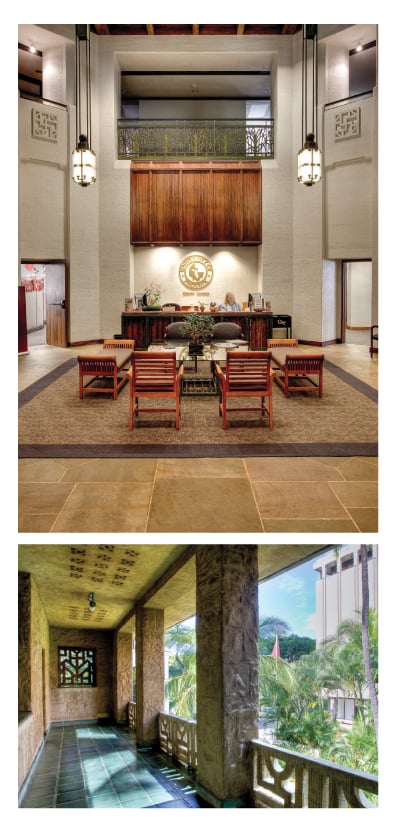

The Mediterranean Revival style of the Alexander & Baldwin building, downtown on Bishop Street, is often described as an example of Hawaiian architecture.

Old and New Buildings

The Mediterranean Revival style of the Alexander & Baldwin building, downtown on Bishop Street, is often described as an example of Hawaiian architecture.

Mason: “There are architects who think historic preservation is not important. They want to do all new modern things. My firm acts as consultants to a number of architectural and planning firms, and sometimes we end up having to recognize and address that tension between preserving and building new. There isn’t one approach that’s right.”

Mehnert: “I agree there has to be a balance between modern work and the preservation of older structures. I call that a dynamic, a synergy. Something very invigorating can come out of it that I have always been very attracted to. I’m a third-generation architect. I was born, raised and educated in Europe. The European approach is that, because we have so much history all around us, you find a mix. You don’t necessarily just restore. You restore, but you also add on. Some of the most interesting buildings I have seen in Europe were those where you have a beautifully restored old structure, and there is a very modern, sensibly done addition. That excites me. What I like about that, too, is that each one of those components of the building were contemporary in their time.”

Hawaiian Architecture

PHOTOS: DAVID CROXFORD

Mason: “There used to be – in the United States, not just in Hawaii – a strong regional movement in architecture. It was partially a reaction to early modernism and partially a reaction to this classical blend of older architectural styles that was in favor for a long time. And Hawaii had a regional architectural movement. There was a very conscious debate, voiced publicly among architects, about what that appropriate style should be. There were people who thought, for example, that a Mediterranean revival style was appropriate to Hawaii. Then, there were other people debating other forms. I think, for a while, we did very much have a regional style here.

“Some people have tried to revive that, but it feels a little forced. It’s successful sometimes, and isn’t successful other times. I’m not sure where we are today, really. Some people are still pushing this sort of 1930s regionalism, but other people are pushing a very modern, more international style. I think everybody here who’s sensitive to design is incorporating or trying to incorporate a respect for the environment. Part of that is design philosophy. Frankly, we are much more conscious about global warming and sustainability, and all of those issues than we were 20 years ago, or even 10 years ago.”

A Cool Example of Sustainability

Menhert: “There are some very exciting things happening now in sustainability. For example, there’s glass that keeps a building cool. Not only does it keep the sun out while still giving you the view, but it reduces the amount of air conditioning needed. I was in a building that used this glass. It was a warehouse structure, a big open space, but when we came from the outside where it was really hot, it felt good inside. We automatically thought air conditioning, but our guide said, “There is no air conditioning.” There were just these huge, Big Ass fans – which is a company name. So, from the standpoint of new technologies that will shape our buildings and what they can do, it’s exciting right now.”

Technology’s Role in Design

PHOTOS: DAVID CROXFORD

“No matter how much virtual reality or sophisticated computer technology we throw at this profession, our work boils down to nice light and a good view. It’s about how buildings and cities and communities make us feel.” —Friedman

Mason: “Design and technology have always been interrelated. There was a time when we only had stone and wood to build with and that informed a lot of our architecture. When you go to a place like St. Petersburg or Paris, you see a whole series of five-, maybe six-story buildings. That’s because they were all naturally ventilated; they were all heated by very primitive means. Those things drove the designs, not only of buildings but of communities. On top of that, in Russia, you had Stalin come in and say, ‘I want all my buildings to look like they’re Beaux Artes buildings.’ And so you get this incredible consistency of design, for political as well as technological reasons. That creates a shared set of characteristics.

The architects agree that the downtown plaza, between the Dillingham Building and the Pacific Guardian Center (right) is a well-designed public space. Another public space, Pauahi Tower at Tamarind Square (left), gets fewer kudos. Photos by Aaron K. Yoshino and David Croxford.

“But technology has changed and we can do all sorts of things now. We can still build things out of brick and wood. But we can also build things out of steel and concrete that are hundreds, if not more than a couple of thousand, feet tall. So why would we expect the same consistency today that these older cities had? We’re back to debating this topic from a philosophical point of view. I’m not sure what the right answer is. I like building buildings of a certain texture and scale, but that’s not for everybody. How do we create neighborhoods that are more similar and have more consistency?

“In places like Kapolei, we tried, through regulation, to create urban environments that have the consistency – in height, color and texture – that everybody loves when they go to old European cities. Well, that wasn’t exactly an entirely popular way of doing things. Even in a historic district, like Chinatown, every once in awhile somebody comes in and says, ‘We need to build a 20-story building on the edge of Chinatown.’ “

Hawaii Business: “Maybe the answer is to design on a more human scale. Part of what makes Manhattan bearable, for example, is that, even though you’ve got all those skyscrapers, at the street level, there are little pizza shops, newsstands and stores. There’s a human scale.”

Mason: “That’s right. I think we have buildings in Honolulu that do that successfully. Many don’t, though. I think Pauahi Tower (on Bishop Street), for example, is not successful. I think it slams into the ground with its dark glass, and you can’t even see into the spaces in there. I consider that to be a poor example because it forgot about the pedestrian.”

Mehnert: “Everything you said about technology is true. It’s exciting now because we have so many more possibilities. So, let’s embrace all of that and do the right thing. Part of the responsibility of the architect is to take all of that and create a good place. ‘Invigorating’ is one of my favorite words, places that do a lot for everyone.”

Which Communities Work Best in Hawaii?

Mason: “I think Chinatown works really well. When my partner, Spencer, and I moved into Chinatown in 1982, there was only one restaurant open. And that closed about a year after we moved in. For one year, there was not a single restaurant open at night in all of Downtown and Chinatown. That’s mind boggling today, but it wasn’t that long ago. It changed, first of all, because people started moving Downtown. The city built some things and they encouraged some things, and now we have a really lively activity center in Chinatown. I am not a particular fan of Waikiki, but I actually think that Waikiki is phenomenal, in terms of pedestrian activity and the unique relationship of activities to the pedestrian. It’s amazing.”

Hawaii Business: “While trying to think of good examples of public spaces in Hawaii, I thought about the redevelopment of Beach Walk. It’s modern, but it draws a lot of people who obviously like to spend time there. The Pacific Guardian Center is another example. The little park between it and the Dillingham Transportation Building is a very successful public space: breezy and pleasant, with little tables and restaurants, so people gather for lunch or just to meet people. Why isn’t there more of that architecture in Hawaii?”

Mehnert: “It’s funny that you bring this up because the Pacific Guardian Center is an Architects Hawaii building. It was before my time, so I wasn’t here when it was built. But the Dillingham Transportation Building was obviously here, and the client said, “Well, you won’t be able to develop around this, so we’re going to have to tear it down.” And we said, “No, let us look at this and work something out.” It’s the architect’s responsibility, sometimes, to gently disagree with the client. And now, look at how lovely this courtyard is.”

Difficult Challenges

Mason: “I don’t think people understand how hard it is to do good architecture. When we go to awards and banquets for architecture,

I come away with real admiration, because I know how hard it is to do what those people did, even if, sometimes, they’re imperfect projects. I’ve never thought any of my projects were close to what I would want them to be. I sit around and find fault in everything I do. So I know how hard it is. And I don’t think people understand how hard it is to do really good design that’s integrated and thoughtful and accomplishes everything not only that the owners want, but that we want as designers.”

Hawaii Business: “Is it because of the tension of having an owner, dealing with rules and regulations, and having your own vision?”

Mason: “That’s all a part of it. But it just takes a lot of work. To get it right, to get the details right, and to make all this stuff work together, you don’t scribble something down on a piece of paper and have it done.”

Mehnert: “I think that’s a key point. People are quick to react to something visual that’s out there. But there’s so much in the building that has nothing to do with design: regulations, all of the codes, very, very technical stuff, the mechanical systems, the selection of components like the glass that we talked about so much earlier.”

Engage the Community

Photo: David Croxford

“Architects say, ‘If you have a really good project, you have a really good

client.’ ” —Mason

Mehnert: “I’ll tell you about one of our projects, the Waikiki Landmark. I think it was the Downtown Planet newspaper that had a survey once a year that I read religiously. One of the things the survey asked was, ‘What’s the ugliest building in town?’ and ‘What’s the best looking building in town?’

When we finished the Waikiki Landmark, which was a huge project, nine years from beginning to end, we had a happy client and everything was generally OK. And, by a landslide, we won first place for ugliest building. I had just started at Architects Hawaii, and we had this discussion about ‘How do you define a successful building?’ And one of the conclusions we came to was a successful building is one the community engages with. It gets noticed. People talk about it. This building certainly accomplished that. And the following year, by a landslide, it was voted best building in town.

Working with Clients

Hawaii Business: “If you had an opportunity, what questions would you ask your favorite architects?”

Mason: “One of my questions would be, ‘How did you get your client to do that?’ When I went to Le Corbusier’s

Ronchamp Chapel, I thought, “How did that client ever find you or you find him? And how did you talk them into that?” That’s one of my chief questions, because there are some wonderful pieces of architecture out there, and a lot of this profession is figuring out how to communicate with your client. Architects say, ‘If you have a really good project, you have a really good client.’ It’s very hard to have great architecture without a great client.”

Loving and Hating Concrete and Glass

Photo: Aaron K. Yoshino

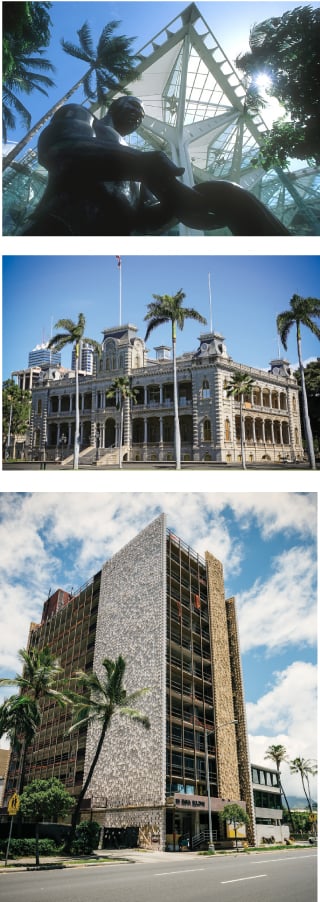

Our contest winners included: First Hawaiian Center; Hawaii Convention Center; Iolani Palace; and the Queen Emma building. PHOTOS: (TOP) DAVID CORNWELL. (MIDDLE) THINKSTOCK.COM. (BOTTOM) AARON K. YOSHINO

People are passionate about buildings in Hawaii.

In August, Hawaii Business launched a social media survey and found people have strong feelings about some structures. Here are the results of the poll along with quotes from survey respondents.

Best Building: A three-way tie among First Hawaiian Center (the bank’s HQ), the Hawaii Convention Center and the Salvation Army’s Kroc Center in Kapolei.

“Kroc Center Hawaii is a great place for kids to stay off the streets and be a part of the community. Maybe not the most innovative or green friendly, but the BEST building to serve the community.”

Best Historical Building: Iolani Palace was the runaway winner, while Aloha Tower was second. However, our favorite description was from a reader who nominated the Moana Surfrider, which opened in 1901 and is the oldest hotel in Waikiki. “It still stands regally in a sea of modern high rises.”

Ugliest Building: The Queen Emma Building across from St. Andrew’s Cathedral was the clear winner (loser?) in this category. The runner-up was Ward Warehouse, which is scheduled to be demolished.

One respondent reminded us of the Queen Emma Building’s derisive nickname, “The Pimple Building.”