Harry Weinberg – Not Your Average Billionaire

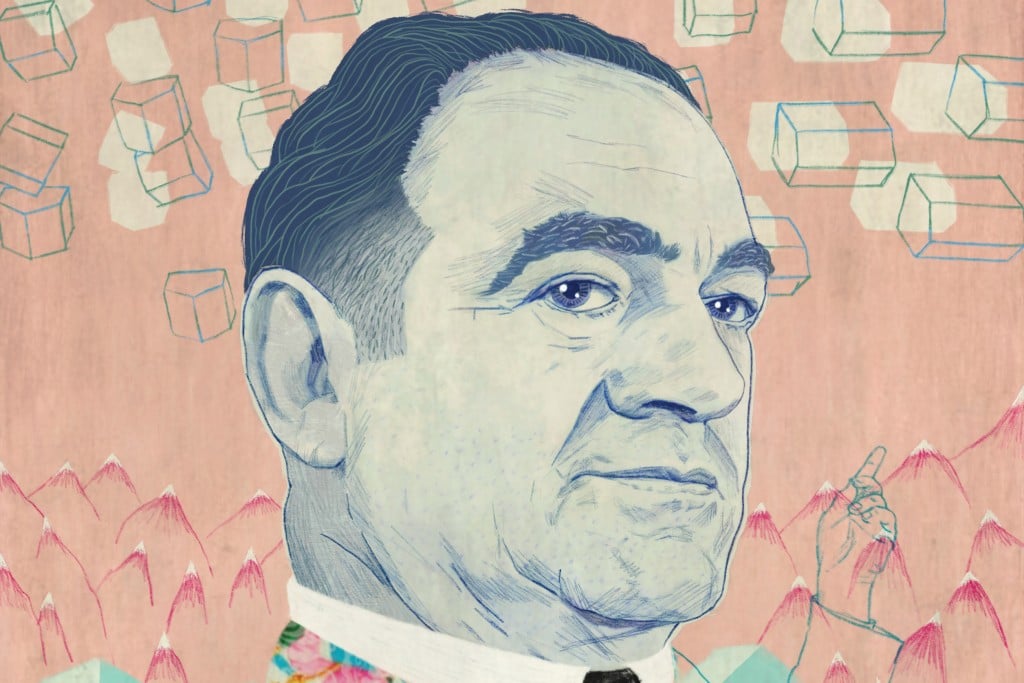

Harry Weinberg amassed a fortune in local real estate and was renowned for being a financially savvy guy, who cajoled and exasperated the top executives of companies he invested in. However, what most surprised Kit Smith, who covered him for decades as a Honolulu Advertiser business reporter, was his disdain for the trappings of wealth. “By no means your average billionaire,” Smith says.

Weinberg was a brilliant guy who came from the streets and didn’t have a formal education, says Walter Dods, retired CEO and chairman of First Hawaiian Bank. “He always felt he could find a better way to do things,” Dods says. “He was very controversial in his day and a really tough guy. But a lot of the things he said turned out to be correct.

The Hawaii Nature Center in Makiki is now named for the Weinbergs. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino.

“I always tell people the irony is all the society people in Hawaii pretty much disliked him at the time and today all of the society people in Hawaii who run major charitable organizations go on their hands and knees to the Weinberg Foundation for donations, so it’s kind of like a full circle. I find it pretty humorous.”

Dods recalls when his former boss, then-First Hawaiian CEO John Bellinger, and Bobby Pfeiffer, then CEO of Alexander & Baldwin Inc., co-chaired a committee in the 1980s to raise money for a new building for Palama Settlement. Back then, Dods says, Weinberg did not give a lot of money to the community. However, Palama Settlement served the poor and that touched Weinberg’s heart.

“They kept pushing and pushing him, and he finally screamed at the two of them, ‘I’ll tell you what. I’ll give a hundred-thousand dollars,’ which in those days was a big gift, and he said, ‘And you go around town and you tell everybody else if a Jew can give a hundred-thousand dollars, you, Amfac, and A&B, and all the major companies better do better than that.’ That was a famous quote at the time that everybody laughed about, but that was kind of Harry Weinberg style.”

ALWAYS AN ENTREPRENEUR

Weinberg was a hard worker and successful entrepreneur from a young age. He and his brothers worked at their father’s car repair shop in Baltimore, but Harry also sold newspapers, American flags and whatever else he could to make money and provide for his family.

Later, he built a transportation empire and owned bus lines in Honolulu, New York, Dallas and Scranton. What made him successful, according to Corbett Kalama, VP of real estate investments and community affairs for the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, was his drive and ability to see value where others lacked enough patience – especially in the real estate associated with those transportation companies.

Weinberg managed money very tightly, says retired Judge Art Fong, recalling a time he stayed with Weinberg in Baltimore. “He owned all these places that he had taken over by foreclosure. So, realistically, he was a smart businessman,” Fong says.

Fong was working at the Hawaii Public Utilities Commission when Weinberg asked for a fare increase for his bus company, which the PUC opposed. Fong describes Weinberg as a fighter who believed in what he did all the way, until Mayor Frank Fasi brought in new buses and the city implemented a public bus system.

Weinberg also bought stock in big local companies, such as A&B and Dillingham Corp., and positioned himself on the boards so he could point out inefficiencies in the organizations. According to Kalama, Weinberg was able to parlay that into owning land on Maui, Oahu and Kauai: “A lot of the land there came as a result of his involvement and his stock ownership in companies.” Today, his foundation owns land in Hawaii valued at $800 million.

Retired Judge Jim Burns says Weinberg was always friendly and courteous with him, but it seemed that his sole priority in life was to accumulate cash and assets. “My conclusion was that, to him, it was a Monopoly game he wanted to win,” Burns says. “Remembering how many people didn’t like him, I smile at what he did with his estate.”

Here are 10 buildings that are named for the Weinbergs or have wings in their names. Clockwise from top left: 1.) The Boys & Girls Club of Hawaii on Fort Weaver Road in Ewa Beach; 2.) the Easter Seals Hawaii building on Renton Road in Ewa Beach; 3.) Catholic Charities Housing Development Corp. on Dominis Street in Makiki; 4.) the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii on Beretania Street in Moiliili; 5.) the Hawaii Nature Center in Makiki; 6.) the Shriners Hospital for Children on Punahou Street; 7.) Goodwill Industries of Hawaii on Lauwiliwili Street in Kapolei; 8.) ARC of Hawaii on Waimano Home Road in Pearl City; 9.) YWCA of Oahu on Wilder Street in Makiki; and 10.) The Queen’s Medical Center-West on Fort Weaver Road in Ewa Beach.

WEINBERG’S LEGACY

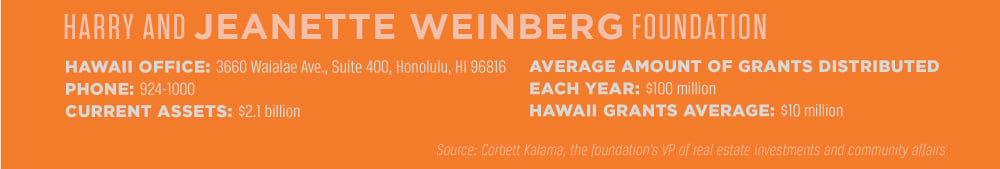

Weinberg established his foundation, named after himself and his wife, Jeanette, in 1959. When he died in 1990, his trust was valued at $900 million. Today, the foundation is valued at $2 billion and, since 1980, has given about $2 billion in grants. “He was a very hardworking visionary who basically had a huge heart,” Kalama says. “He was a strong advocate for those who were less fortunate and a model for people to follow. He could very well have just lived a very luxurious life but he lived very frugally because his mission in life was to work for the poor and needy.”

When Smith covered business news for The Honolulu Advertiser, he interviewed Weinberg a time or two in his ground-floor Iwilei office. Smith thinks Weinberg almost took pride in the place being so bare, adding that Weinberg had a gruff exterior and spoke in short sentences, but Smith sensed he had a good heart. “My goodness, look at all the charities he has supported.”

Weinberg’s foundation gives out 5 percent of its value every year – about $100 million – to nonprofits around the world. Hawaii receives about 10 percent of that sum – since 1990, more than 700 nonprofits in the state have received a total of $315 million.

Reuben Wong, 80, who served as a personal attorney to Weinberg and his Hawaii companies for 19 years, says this has benefited the people of Hawaii greatly, especially now that many of the big companies – like Dillingham Corp. and Amfac, that used to donate to charity – don’t exist.

His charity is visible in the 183 buildings named after Harry and Jeanette Weinberg in Hawaii. At least 50 percent of the foundation’s grants have to be capital grants – the rest can go toward programs and operating costs. When nonprofits receive capital grants valued at $250,000 or higher, they are required to name their buildings after the couple. Kalama says the foundation will then finance up to 30 percent of their projects, but the amount cannot exceed $3 million.

To qualify for a grant from the foundation, nonprofits must have been in operation for at least three years. They must also provide direct services to low-income and other vulnerable populations.

The foundation’s focus on the poor and needy stems from Weinberg and his family receiving aid when they were poor, Kalama says. “One such situation was when they went to a hospital, the hospital never would charge them for their services, so one of the things that Harry did was make a $2 million contribution to that hospital in Baltimore.”

“Had it not been for the assistance they received from philanthropic groups, life would have been much more difficult. He never forgot that.”

This map shows facilities across the Hawaiian Islands funded by the Weinberg Foundation since 1990. A few are no longer there. Also, since facilities are sometimes located near one another, a single dot may stand for more than one facility. (click to enlarge)

THE VALUE OF LEGACIES

The Hawaii Community Foundation wants others to see the importance of estates and legacy gifts, like the one Harry Weinberg created with his foundation.

To encourage more such legacy gifts, HCF launched its Hawaii Legacy Giving Campaign last year, its 100th anniversary. The foundation has been providing nonprofits with tools through workshops, meetings and webinars to help them increase the legacy gifts they receive. Currently, HCF has partnered with more than 100 organizations.

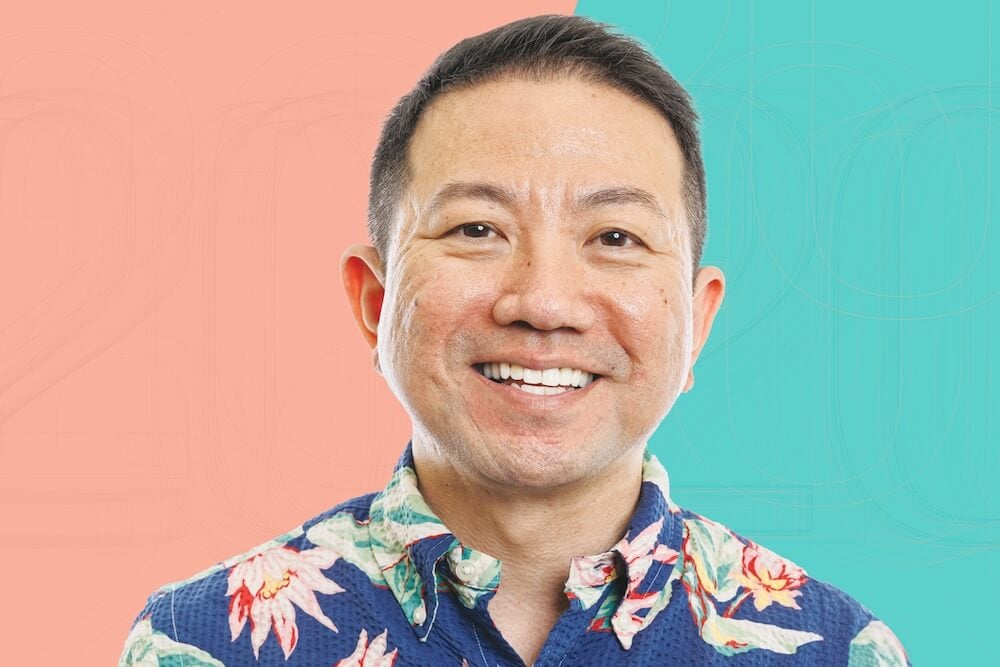

The primary focus is to help organizations get over the discomfort they may feel when talking about legacy giving, because people tend to relate such gifts to death, says Curtis Sakai, VP of philanthropy and general counsel at HCF.

Liz Makarra, development manager at the Waikiki Health Center, says the foundation’s campaign encourages the center to create deeper relationships with its donors and to open the door to conversations they wouldn’t normally have on a daily basis. “Many of them have been supporting us for many, many years, so that challenge is just getting out of our comfort zone and, for lack of a better word, in a loving and respectful manner, encourage them to think about leaving a legacy and what that means. And really that means: Consider us when making your will and in trusts,” Makarra says.

Inger Tully, development director at the Maui Arts and Cultural Center, says the foundation’s toolkit, which includes resources such as sample letters, walks the nonprofit through the nuts and bolts of legacy giving. As with the Waikiki Health Center, this campaign has put legacy giving at the forefront of conversations, especially with Maui Arts and Cultural Center’s development committee and board, Tully says.

According to HCF’s Planned Giving Toolkit, nonprofits in Hawaii could receive $6 billion if every high-net-worth household left 10 percent of its estate for charity. HCF’s legacy campaign will continue through 2017, Sakai says.

“Hopefully, what we’ll do is get organizations to a place where they develop sort of muscle memory in doing this activity so that, after the campaign is over, they still continue to have a strong legacy giving component in their fundraising.”

“IT’S IN THE DNA OF HAWAII”

Hawaii has a strong giving culture: Almost all households donated cash, goods or time in 2014, with nearly two-thirds giving cash, according to the Hawaii Community Foundation.

“I think that’s just the culture of Hawaii and the spirit of aloha and certainly the role models from the alii to the missionaries and on till today,” says Curtis Sakai, the foundation’s VP of philanthropy and general counsel. “There’s a great engaged population that cares about each other and takes care of the community. I think it’s in the DNA of Hawaii.”