Guide Your Family Business With Good Planning

The boss called one of his employees into the office. “Rob,” he said, “you’ve been with the company for a year. You started off in the mailroom, one week later you were promoted to a sales position, and one month after that you were promoted to district manager of the sales department. Just four short months later, you were promoted to vice president. Now it’s time for me to retire, and I want you to take over the company. What do you say to that?”

“Thanks,” said the employee.

“Thanks?” the boss replied. “Is that all you can say?”

“I suppose not,” the employee said. “Thanks, Dad.”

If there’s a pervasive stereotype of family-run businesses, that old joke pretty much covers it. The reality is far more complex, but the punch line hints at two difficult issues that often crop up in family-run businesses: succession and entitlement.

Neither issue is a joke to members of family businesses or their employees who experience it. When family problems get in the way, or if the boss’ son or daughter catapults to the top without understanding what makes the business run, or a relative continues to draw a paycheck despite poor performance – bad planning is to blame.

Consultant Mike Miyahira, founder of Business Strategies, says that when family businesses encounter problems, three areas usually need immediate attention: succession planning, entitlement issues, and governance structures for both the family and the business itself.

Miyahira, who started his own family-business consulting service after retiring from Bank of Hawaii 15 years ago, says poor or no succession planning tops the list of reasons family businesses founder or fail.

“When you consider the benefits of succession planning, you wonder why more owners of family businesses don’t pursue it,” he says. “Proper planning engages the next generation, it helps to prepare it for possible ownership and managerial responsibilities, and facilitates an orderly transition from one generation to the next.” Proper planning might even begin with a family business constitution.

Despite “a ton of literature out there on family business constitutions,” Miyahira guesses there’s little awareness of this important tool outside of family-business centers, where stories are shared in confidence and solutions are considered.

A family business constitution is a collection of policies that govern the interaction of family members with their business. It might include policies on employment, retirement, ownership, accountability, as well as a code of conduct. It is designed to minimize conflict. It might save the business and family relationships.

That brings to mind another critical document for the business: a mission statement.

“If you ask business owners the primary purpose of their business, invariably the answer is, ‘To make money,’ if they can’t think of anything else,” Miyahira says. He argues that the real driving force and mission of the business is often lost between generations.

“Business owners should periodically revisit the question of what they are in business for. Having a purposeful mission for your business can be a strong motivator, not just for the current owner, but for succeeding generations as well.”

Long-term Planning

Kurt Corbin, assistant state director for the Hawaii Small Business Development Center, says several complexities can affect family-owned businesses as they transition from one generation to the next.

Family-owned businesses can be identified by their “family-first” predisposition, Corbin says. They tend to “trust a family member to put the interests of the family first,” even if an outsider might offer better skills and experience, he says.

“Deciding who will run the business and work in it becomes a paramount issue. Another is managing the performance of family members who are employees.”

Few small businesses of any kind plan for the long term or for succession the way well-run big businesses do, by constantly asking: “Who is moving up to the management ranks or who are we sending off to training programs?”

“In smaller businesses, in family businesses, for example, if it’s a printing business, you pretty much know you start out by sweeping up at night and you learn how to run the presses and answer the phone and work with customers. In smaller companies you end up learning a lot just because you have to.”

Even though many of the people we spoke with had worked in their family business at some point in their youth, most emphasized they had explored other pursuits before formally joining the family business.

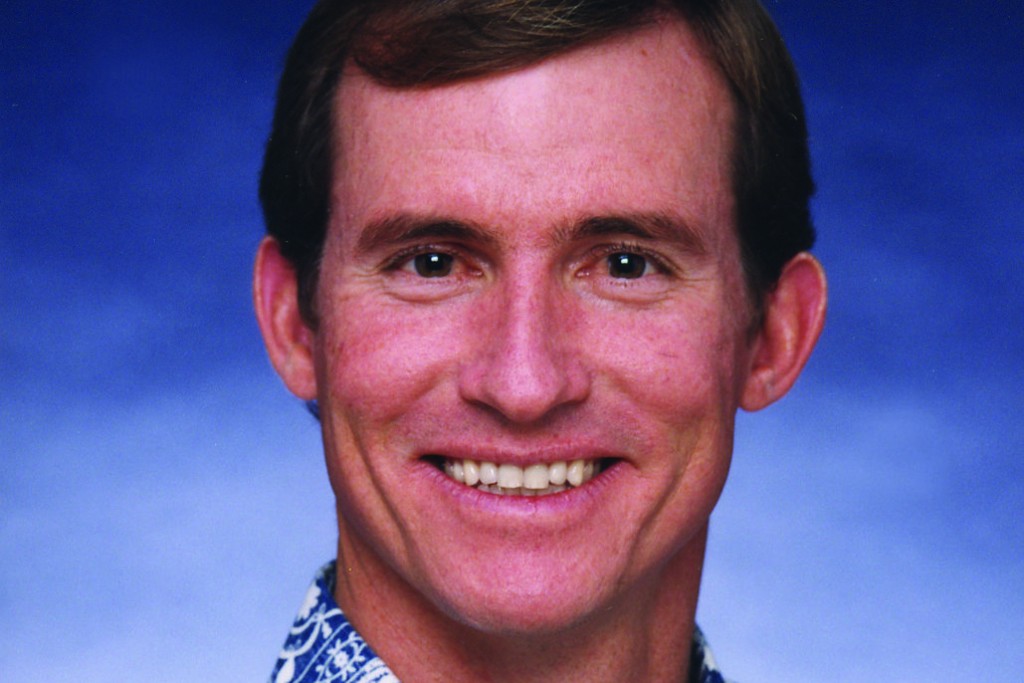

Chuck Kelley, G-3

Chuck Kelley, chairman of the board of Outrigger Enterprises Group, didn’t join the family business until 2001, after a 15-year career in internal and occupational medicine at Straub Clinic.

“It’s just kind of best practice to do that,” he says. “Many family businesses today encourage their children to work outside of the family business because family businesses have a large chance of failing and because it’s just important to have family members experience success on their own.”

Kelley identifies as G-3 – shortcut, he says, for third generation in the business. Growing up, his dad, Dr. Richard R. Kelley, was at the helm of the family business started by his father, architect Roy Kelley, a pioneer of post-World War II Waikiki hotels.

Six family members are active in the business today: Richard Kelley, Richard’s sister, Jean Rolles, Chuck and his siblings, Bitsy and Linda, and brother-in-law David Carey, president and CEO of the company. The company owns or operates hotels throughout Hawaii and across Asia and the Pacific.

Kelley laughs remembering how he and his siblings “worked” for the Outrigger at their dad’s request when they were kids.

“I don’t think we were very helpful. When we had vacations or time off from school, my dad would place us in various departments to learn as much as we could: front desk, maintenance, housekeeping, construction.”

Helpful or not, “I think we were pretty typical of kids of family businesses in that family life is centered around the business.” He understands now that his dad’s goal was more to teach a good work ethic and to help them understand the business.

Kelley is grateful for UH’s Family Business Center of Hawaii and says it is one of the places Hawaii families can go to discuss in confidence issues related to their own family businesses.

As for the Kelleys, “We’ve been involved in learning about family businesses for a long, long time – since I was in my 20s. My father was quite active with an organization called Young Presidents Organization and he met some speakers through that who started talking about the importance of family businesses. We would meet with those advisors to talk about what we could do to increase the likelihood that we could continue to be a family business, working together. We worked with various outside consultants with a similar organization called the Family Office Exchange for many years, again networking … and learning what were considered best practices.”

UH’s Family Business Center came along later, he says, when “the whole field of family business became more popular and interesting to a wider variety of families all across the U.S.”

Informed by best practices, the Outrigger’s mission statement and values reflect its corporate culture of ohana and hospitality while the Kelley family also has its own governance structures in place, among them a family constitution.

Samuel W. Pratt, G-4

Samuel W. Pratt is president of Niu Pia Land Co. Ltd., a family-owned business that owns and manages commercial real estate investments in Hawaii. Pratt’s great-grandfather, Edward H. W. Broadbent, a blacksmith by trade, hopped a steamer from New Zealand headed for the U.S. mainland in 1891, disembarked in Honolulu and settled on Kauai. Some 20 years later, he began purchasing land there – eventually acquiring 180 acres of pasture and coastal properties used for ranching (cattle and pigs) and farming niu (coconuts) and pia (cassava) until about 1960.

Broadbent’s children (G-2) took over management of the properties and incorporated Niu Pia Farms Ltd. in 1963 and, during the 1970s, Broadbent’s grandchildren (G3) began to serve in leadership positions.

Pratt (G-4) says that in 2001, Niu Pia “was transformed from a passive land-leasing company on Kauai to an active landlord of commercial real estate with property across Hawaii” through 1031 tax-deferred exchanges. The company celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2013 and is striving to engage the G-5 generation in participating in the family company, he says, similarly to how his generation learned the business through “early involvement with the previous generation.”

Along the way, this family business suffered a rift. “One (of three) branches of the family exited the family business as owners since their needs were not consistent with the majority of shareholders,” Pratt says. “This included a lawsuit against the board by the largest shareholder, who eventually agreed to sell his shares back to the company.”

Members of the 4th generation at Niu Pia Land Co. Ltd.: From left, Bill Pratt, VP and director of sales and leasing; Samuel Pratt, president; and Melinda Walker, secretary and director of property management. Photo: David Croxford

Sandra “Sandy” Au Fong, G-2

Sandy Au Fong is president of Market City Ltd., consisting of Market City Shopping Center and other commercial and residential real estate properties and investments. Her husband, Marvin Fong, chairs the board and younger son, Tim, is VP.

Market City Shopping Center celebrated its 65th anniversary last year. In 1948, Hiram Fong (Sandy’s father-in-law and later a U.S. senator from Hawaii) went in with two other families to transform a 3.5-acre vegetable and koa patch at the corner of Kapiolani Boulevard and Kaimuki Avenue into a shopping center for residents of Kapahulu, Kaimuki and Moiliili.

Sandy and Marvin married in 1974 and eventually went to work for the company, bringing the family-owned enterprise from a negative to a positive cash flow. They feel fortunate to have been among the early members of the Family Business Center of Hawaii. In 2000, they bought the shopping center.

Because the purchase involved a prominent local family, the news media covered what happened next. It is not something Sandy wants to talk about: There was a court case, the judge cleared the way for Marvin and Sandy to buy the other invested parties out of the company, and a bank gave them a loan to do so.

It was a painful time and, after all the family has been through, Sandy knows, “Good planning is the most important thing you can do in a family business.” She talks to her family all the time and has told her children, “We’re going to pass the business on. If you are not getting along, sell it.”

She hopes their two sons will enjoy a good family life, a good business life and give back to the community. But if things don’t work out – as they sometimes don’t – she’s glad they’ve adopted policies to ensure that each one has a voice.

“The old generation believed in never selling and everybody stays together. No, if somebody wants to get out, you should find a way for them to get out. You should have a buyout clause.”

Sandra “Sandy” Au Fong, her younger son, Tim Fong, and her husband, Marvin Fong. Photo: Lee Ann Bowman

Why plan ahead?

In her 20 years of business banking experience, Naomi Masuno has witnessed many scenarios that can derail or destroy a family business. She has seen children who don’t want to take over the business, so the parents keep working into their senior years; children who were never cross-trained because a parent was too domineering; family members who run the business into the ground because of excesses in lifestyle; or a divorce or death settlement that puts a financial strain on the company.

Masuno, vice chair of the Patsy T. Mink Center for Business & Leadership, recommends every company have “competent, trusted advisors to help guide them with an exit strategy, which should include retirement and estate planning.”

“Whether it’s selling the company to employees or to a new owner or having the next generation take over, business owners should put their strategic plan in play early. Some of the measures to mitigate future problems can easily be taken with insurance policies, trust agreements, training programs, operating agreements, etc.”

David Arita, G-1

David Arita, American Carpet One’s president and only stockholder, grew up in a family business, a chicken farm in Waialua. He and his older brother did whatever needed doing with chickens: slaughtering the fryers, feeding, picking up, cleaning and weighing eggs to assign them to cartons of small, medium and large. After earning a degree in engineering at UH-Manoa, he discovered he didn’t like the engineering field and found a job as a part-time carpet salesman for Wigwam.

In 1974, he and a friend, Stan Koki, started the business with five employees. Arita bought out Koki in 1990. For more than 25 years, Arita’s parents, Satoru and Doris Arita, were on the payroll, maintaining the grounds, perimeter lots and company vehicles. Arita’s wife, Christine, worked in the business for more than a decade as well. Son, Daniel, is now VP of operations.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of ACO, which today employs more than 100 people and is the workplace not only for David and Daniel, but for other employees who have “brought in their children or siblings into the business.” Arita proudly names them, the family member they brought in and the department each works in. It’s important, he says, to have employment policies that address issues before they arise. For instance, one ACO policy is simple: Family members can be in the same department, but cannot be supervised by another family member.

Following an invitation from an old friend several years ago, Arita attended a meeting of the Family Business Center of Hawaii. The friend had brought his own son to a meeting and later both Arita’s son and the friend’s son met at an FBCH retreat.

David Arita, a co-founder of American Carpet One, and his son, Daniel Arita. Photo: David Croxford

G-3 Wonders What’s Next

At least one third-generation family member and “likely” next-owner/manager wishes he had someone of his generation he could talk to. The soft-spoken young man, who wishes to remain anonymous, has long assisted a parent with the endless paperwork of their family business, a small property management business that includes a retail complex in a resort community. It was his late grandmother who thought to turn family-owned land into a revenue-generating entity. Documents drawn up a half-century ago still guide the business.

“Some of my generation can hardly wait to get in on ‘the money,’ ” he says ruefully. “What they don’t realize is there is not that much of it and they have no idea of the work it entails.

“They hear about things being done by other entities or they see things in the media. But they have little or no knowledge of how our business came about or what it’s like to manage a business in another locale.”

He wonders what will happen when suddenly something shifts.

Getting Started

What if there is no succession plan? The first move must come from the company’s leader, says Jean Santos of Business Consulting Resources Inc. She and her husband/partner, Ken Gilbert, counsel family businesses and other companies.

The main family members involved need to talk to each other, she says. If they don’t know where to begin, Santos suggests they start by asking a trusted attorney, banker or CPA for advice. The most important thing is to establish trust and confidence in this advisor. If the family can’t find that, they need to move on until they find someone they can trust.But somebody’s got to start the discussion. “That’s the exciting thing for that third generation. They’ve got such a strong foundation. Now they’ll have an opportunity to really start dealing with the processes and getting the business more organized, more efficient and more profitable.

The third generation can have the luxury of moving beyond the business’ early concerns of paying bills and establishing a reputation, and focus on taking the business to the next level, Santos says.

“Typically, if mom or dad is in the second generation, their approach to running the business is vastly different from what the third will perceive. (G-3) grew up with iPhones and smart phones – they want to look into running things in a new and technologically driven way.”

But, Santos cautions, “It’s important that families realize this is a process. It doesn’t happen in one meeting. … It takes a commitment from everybody – from the current leader to the kids. And it gets messy and challenging.

“People need to be willing to go through that and realize you’ll come out on the other side, but it takes focus and time.”

Help Is Available

Family Business Center of Hawaii

956-5083

fbch@hawaii.edu

www.fbcofhawaii.org

Business Strategies

Michael Miyahira

(808) 987-8328

mike@bus-strategies.com

Business Consulting Resources Inc.

Jean Santos, Ken Gilbert

545-4111

jean@bcrhawaii.com

ken@bcrhawaii.com

Hawaii Small Business Development Center

(808) 945-1430

www.hisbdc.org

Patsy T. Mink Center for Business & Leadership

695-2636

www.mcbl-hawaii.org