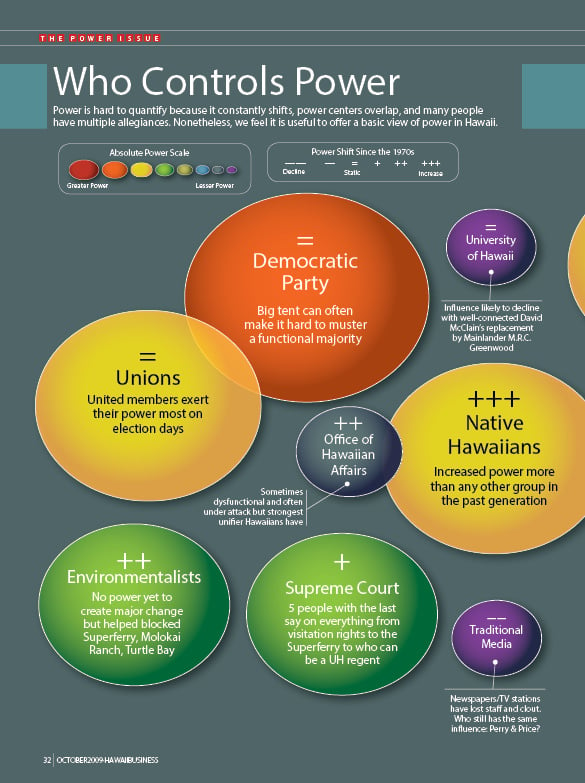

Good News, A Small Power Elite No Longer Runs Hawaii. Bad News, Nobody Does…

If Hawaii is to answer the major questions confronting the state – How do we create a healthy economy while preserving what makes Hawaii special? How do we improve our public schools? How do we sustain effective government? – we first need to deal with the fundamental issue: What has happened to power?

In 1964, the story goes, when Gov. Jack Burns became concerned about the effectiveness of Hawaii’s most important charity, the Community Chest, he didn’t hold hearings or try to drum up public support in the media. Instead, he summoned two community leaders to his office — labor activist Jack Hall and Lowell Dillingham, dean of the Bishop Street crowd — to remind them of their civic responsibilities.

“Boys,” the governor is supposed to have told them, “something’s broken here, and it’s up to you to fix it.” In most versions of this story, these two old antagonists set aside their differences and worked on the problem. By the time they left the governor’s office, they had outlined an organization that would eventually become the Aloha United Way, with Hall serving on the board to secure the support of labor, and Dillingham, with the imprimatur of Big Business, as its chair.

Stories like this, many apocryphal, are parables of a time in Hawaii when power and leadership were exercised much differently than today. In that era, when the Big Five still dominated the business community and the great Democratic political machine was reaching its zenith, it still seemed possible for a governor to lead without equivocation, to decide unilaterally on a course and then act. Perhaps more importantly, it was still possible to identify a core of community leaders, men like Hall and Dillingham, who had the status and force of personality to get things done.

Today, it is probably Mufi Hannemann who most closely resembles Hawaii’s earlier generation of power brokers. Although he advocates collaboration and consensus, he says that’s not enough. “It’s important to listen; but, in my opinion, listening also requires action.” | Photo: Kevin Blitz

For many of those who lived through that era, there’s a nostalgia for the simplicity of its power structure. It was, of course, a much less democratic age, a time when a few men (and they were all men) made most of the important decisions for the state. But, as David Heenan puts it, “Many people respect an oligarchy.” Heenan, former CEO of Big Five company TheoDavies, and now a trustee for the Campbell Estate, is no apologist for the excesses of that earlier age. But it’s hard to ignore the advantages of concentrated power. “When I was involved in Big Five stuff,” he says, “and with companies like Dillingham and Pacific Resources, the two estates, and the two big banks, back then, there were eight or ten people you could turn to. You could get those guys in the room and get things done. There was gravitas there.”

And it wasn’t just in the business community. “It was the same thing on the political front,” Heenan says. “You had the Burns machine, and then Ariyoshi. There was more of a notion of centralization. And although the unions may have been larger than today, actual power lay in the hands of just a few people, men like Jack Hall, David Trask and Art Rutledge.

“You could identify the players,” Heenan points out. “They all had some real clout. Then that got fragmented by globalization and technology and so forth. Now, you’re trying to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.”

Today, that fragmentation of power is the central feature of Hawaii’s political and cultural landscape. It’s blamed for everything from the failure of the Superferry, to the confusing, on-again, off-again saga of Act 221, to the seemingly endless squabbling over Honolulu’s rail project. And, if Hawaii is to answer the major questions confronting the state – How do we create a healthy economy while preserving what makes Hawaii special? How do we improve our public schools? How do we sustain effective government? – we first need to deal with the fundamental issue: What has happened to power?

A Failure of Leadership

“To me, the biggest disappointment has been the leadership,” says Heenan. “And I’m part of it.”

The Big Five sugar plantation companies and their leaders, including David Heenan, were once the core of Hawaii’s power elite. | Photo:

Indeed, one of the great ironies of the current crisis of power is that it’s possible to trace its origins directly to the failures of leadership from the Big Five era. There’s still some nostalgia for the last of these leaders — men like Heenan, Herb Cornuelle of Dillingham and Henry Clark of Castle and Cooke, who presided over not only their own companies, but many of the state’s civic organizations. But it was the inability of these companies, under their leadership, to adapt to the decline of agriculture that spelled the end of the Big Five. One by one, they were gobbled up by offshore corporations or succumbed to piecemeal liquidation. By the mid-1980s, all but A&B were gone.

As these leaders disappeared, they took with them a style of leadership that was both more personal and more willing to acknowledge a debt to their community. One prominent local businessman put it succinctly: “Today, we’re really stuck with a colorless group of leaders.” Although there are still a few business leaders – old-timers like Walter Dods or Jeff Watanabe, whose power and influence crosses into the civic and the political arenas – it’s hard to imagine who their successors will be. Today’s business leaders are much more focused on their own narrow corporate interests. This growing factionalism in the business community is emblematic of what’s happening in the broader society. There’s simply much less communication between different groups. And yet, this reaching across lines is often the sign of real power.

Senate President Colleen Hanabusa says that, then and now, personal relationships are a big part of getting things done in Hawaii. | Photo:

According to Senate President Colleen Hanabusa, getting things done isn’t merely a matter of more negotiations; it also has to be personal. “You’ve got to put a face to the issues,” she says. She likes to use as an example the friendship between the former union leader Art Rutledge and the prickly business magnate Harry Weinberg. She points out that, although they were often on opposite sides of contentious labor negotiations, “They had a great relationship. And when Weinberg was sick, it was Mr. ‘R’ who would go to see him.” It’s a lesson Hanabusa has taken to heart. She mentions her close relationship with Senate Republican Sam Slom. “I don’t think I could tell you that there’s a better colleague, a better friend in the Senate,” she says.

New rules

Hanabusa is also one of the few people mentioned by business and community leaders as an example of an old-fashioned, arm-twisting politician. But it’s a reputation, she says, that has more to do with her argumentative style than the quality of her leadership. In fact, she sees herself at the vanguard of a more collaborative type of legislative leader. “In the old days,” she says, “if you didn’t follow what the leadership wanted, you didn’t get CIP – Community Improvement Projects. The way we operate as a legislative body now, it’s much more of a shared decision-making concept. If there’s anything new, it’s the sense that, unless we have consensus, whatever we do is not going to sustain.”

Even Mayor Mufi Hannemann, whose charismatic and forceful style of leadership most closely resembles the old-time powerbrokers, preaches the twin doctrines of collaboration and consensus. But he gives them a more didactic cast. “Leaders,” he says, “sometimes make the mistake of sitting behind their desk, or hiding behind their cadre of PR doctors, and hoping the public will ‘get it,’ or that the nature and power of their office will win the day. But those days are gone. I don’t think sitting around with four or five power brokers is going to do it anymore. I think you’ve still got to sit with those four or five powerbrokers and get their ideas. But, at the end of the day, you’ve got to go sell it to a Joe Kamaka in Waianae; you’ve got to go sell it to a Helen Suzuki in Manoa; you’ve got to go sell it to a Larry Smith in Hawaii Kai.”

But he points out that the power of consensus doesn’t come from simply listening to what others have to say. “Sometimes, that word is overused,” Hannemann says. “It’s important to listen; but, in my opinion, listening also requires action.” He uses the example of rail: “It’s not my idea. It’s been around for years. But we executed very well to be able to get a tax increase passed in one legislative session – with a Republican governor who wanted to do it three years before, didn’t do it, and then has had second thoughts every step along the way.” As much as anything, it’s been his ability to keep rail moving forward that makes the mayor a touchstone in any discussion of power in Hawaii. And the ultimate success or failure of rail will likely affect Hawaii’s map of power for decades to come.

Offshore ownership

Of course, local leadership is not entirely to blame. Money is power and so much of Hawaii’s money is now controlled from the Mainland and overseas. Look at the growth here of companies that are headquartered elsewhere. In the Hawaii Business Top 250, the number of companies with out-of-state headquarters has changed only modestly since 1983 (up from 26 percent to 30 percent), but those offshore companies’ share of gross revenues jumped from 19 percent to 32 percent. That’s about a 70 percent increase in outside financial control.

Most CEOs of locally owned companies are well known to local nonprofits and serve as donors and board members. But the local managers of companies headquartered elsewhere rarely have the authority or personal wealth to serve as community leaders.

Even this number underestimates the power shift, since many large Hawaii corporations with out-of-state ownership did not participate in the Top 250. That includes retailers like WalMart, Costco, Macy’s and Target, and media companies like The Honolulu Advertiser. These and similar companies represent tens of thousands of employees and billions in revenue. If they were local companies, their owners would be major power brokers in the state. Instead, the companies are run by branch managers and have a ghostly, neither-here-nor-there quality.

Offshore ownership means important decisions about Hawaii’s future are often made beyond the influence of Island politicians or community leaders. Projects are planned, funding secured and assets managed from offices in New York, Los Angeles or Tokyo. Because they happen over the horizon, these business decisions are often made with little regard for their impact here.

But the dispersion of power is even more insidious. Traditionally, Hawaii’s powerful business leaders also used their influence and wealth for civic purposes. They served as directors and major funders for most of Hawaii’s nonprofits. They bankrolled and advocated for politicians and social issues. Each generation of leaders incubated its successors. In short, Hawaii’s business leaders and the power they wielded were valuable community assets. But as their power diminished or migrated offshore, it became harder for the community to tap that resource. For example, most CEOs of locally owned companies are well known to local nonprofits and serve as donors and board members. But the local managers of companies headquartered elsewhere rarely have the authority or personal wealth to serve as community leaders. The result is a more anemic civil society.

Attorney Bill Meheula says Native Hawaiian and environmental groups have pushed for laws that now give them more power over development. | Photo:

Even companies with seemingly impeccable Island pedigrees – firms with local headquarters like Alexander & Baldwin, Bank of Hawaii and Hawaiian Electric – have seen their influence move offshore. Many are publicly traded companies, including seven of the 10 largest for-profit companies in the Hawaii Business Top 250. Their managers may still have strong local commitments, but ownership is dispersed across the country, even the world. The old kamaaina families that founded these companies and, for better or worse, presided over Hawaii civil society for nearly a century, have largely divested their interests in the family businesses. There are no Baldwins left on the board of A&B; no Castles preside over David Murdock’s Castle and Cooke. These families, through trusts and charities, still exert some influence over Hawaii’s future, but their power is largely dispersed.

The power of lawsuits

Perhaps the most obvious change in Hawaii’s power landscape has been the growing clout of environmental, Native Hawaiian and related interest groups. A generation ago, developers scarcely gave them a thought; today, with a mix of grassroots organizing and litigation, nonprofits like the Sierra Club, Kahea and Life of the Land have become gatekeepers for almost every major project in the Islands. This is part of the democratization of power, as control over change has broadened from an elite to more people. But critics point out that almost every time Native Hawaiian or environmental groups have stopped a project, the telling blow has been a lawsuit. This reliance suggests that these interest groups only have the power to stop things, not the power to get things done.

Bill Meheula, an attorney who has worked both as a development litigator and as a pro bono representative for Native Hawaiian groups, acknowledges that the threat of lawsuits has radically changed how business gets done, adding to the cost and time of development in Hawaii. But he points out that litigation is only possible because these groups have been successful at getting laws passed that support their interests. “I think that the lobbying efforts have grown in favor of environmentalists and Native Hawaiians,” he says. That effort, the steady application of the political process, is the true source of power for these groups, he says. In this way, they’re not that different from the Labor Movement in the middle of the 20th century.

Richard Harris of the Sierra Club says development can move forward today if companies seek community input and address legitimate concerns.

Robert Harris, executive director of the Sierra Club, uses the Superferry as an example. “Superferry was very obvious to most lawyers,” he says of the early decision by the Lingle administration to bypass an environmental impact statement. “The decision made by the administration was just wrong. Even the state auditor knew that this was a clear violation of the law,” Harris says. In other words, the demise of Superferry is another example of a failure of leadership, a misguided attempt to circumvent a legal process.

New way to power

But, according to Harris, it doesn’t have to be that way. He points to First Wind’s Kaheawa alternative-energy project on Maui as an example of a company that found a way to get things done. “That was a company that really went out and engaged the community,” Harris says. “And it’s a project that, when they went for their permits, actually had significant environmental issues. It was on conservation land; there were endangered species issues; there were water issues. But they actually had strong community support.”

“Don’t just come here to sell a project based on ‘it will create jobs.’ … You need to say why this would be good for this particular community.”

– Mufi Hannemann

Hannemann points out that this is simply the new reality of power in Hawaii. “Don’t just come here to sell a project based on ‘It will create jobs,’ ” he says. “That’s not enough anymore. You need to incorporate some community benefits. You need to say why this would be good for this particular community. And you’ve got to sell it. You can’t look to a political person or a fancy PR firm to do it for you. You’ve got to go out and do it yourself. If your idea is a good idea, if your project is a good project, it will stand the test of time and scrutiny.”

But it’s probably not the mayor’s consultative side that gets the attention of Hawaii’s power mavens. It’s his political ability to get things done in the face of strong opposition. “Maybe it’s just me,” says Dave Heenan, “but my own sense is that people respect can-do leaders. I think people are somewhat burned out by all this consensus seeking. It ends up being just meeting after meeting, and all of a sudden, the window of opportunity closes.” So, even some of those who do not like the mayor, or are ambivalent about rail, find themselves quietly rooting for his success.

Heenan notes with dry approval, “Hannemann – for all he is and isn’t – at least had the balls to take on this thing.”