Geothermal’s Second Chance

When geothermal steam was first harnessed to generate electricity on the Big Island almost three decades ago, the project left many residents with a bitter taste. The technology was substandard, the community wasn’t consulted and environmental protestors became fixtures outside the plant.

Some residents still see the Island’s volcanoes as a sacred power that should never be commercialized. But today, the high price and environmental damage of oil has helped persuade many others – including some former opponents – to re-evaluate geothermal’s potential to generate more renewable energy and stimulate a struggling Hawaii Island economy.

“I think most people here see geothermal as a positive thing,” Big Island Mayor Billy Kenoi says. “But it has to be done right this time. We’re not going to ‘Superferry’ any more major community projects. The lesson here is: Talking builds trust. You cannot rush. … The more time and effort you put in on the front end, the easier it is, the more collaborative and cooperative it is on the back end.”

Right now, geothermal supplies 20 percent of the Island’s electricity, but Kenoi hopes it will soon help Hawaii Island become the state’s first county to get half of its energy from renewable sources.

Mililani Trask, attorney and Native Hawaiian advocate, says she supports responsible geothermal development. “It’s crucial that the community has a say in what goes on to prevent the same mistakes from happening.” | Photo: Rae Huo

Tumultuous past

The first geothermal well in Hawaii was drilled by the state in 1976 and began producing electricity in 1982. Originally designed as a two-year project to prove geothermal energy production was possible, the plant operated for seven years.

“People criticized it for being unsafe and irresponsible,” says Mike Kaleikini, plant manager for Puna Geothermal Ventures, Hawaii’s only remaining geothermal power site. “From the very beginning, geothermal faced tremendous struggles – and rightfully so.”

Image: Hawaii Tribune

Soon after the pilot program, a project on Campbell Estate land almost turned Puna into a battleground. More than 1,000 protestors assembled near the entrance of True-Geothermal’s drilling facility on March 26, 1990, claiming the development hurt nearby Wao Kele o Puna, the state’s largest remaining lowland wet forest and a sacred place for Native Hawaiians. More than 130 people were arrested that day. Eventually, after years of opposition and litigation, the Wao Kele o Puna geothermal project was abandoned.

“(Wao Kele o Puna) was put together for private benefit with no consideration for the impact it would have on the community or the environment,” says attorney and Native Hawaiian advocate Mililani Trask, who was at the protest two decades ago. “The previous model had no ideas for benefit sharing and the technology was poor. The goal was for the company to get rich and nobody else. It was a mismatch of science, technology, the resource and management.”Today, Trask says there have been significant advances in technology and Hawaii has more national and global experience from which to draw.

“We can’t go backwards in time,” she says. “This time around, I am in favor of responsible use and development of the resource.”

Around the same time, in 1993, Puna Geothermal Ventures began its commercial operation with a power-purchase agreement with the Hawaii Electric Light Co. to provide 30 megawatts. PGV, which is owned by Ormat Technologies, based in Reno, Nev., sits on the lower East Rift Zone of Kilauea volcano, adjacent to Wao Kele o Puna.

Mike Kaleikini, plant manager for Puna Geothermal, says the company is doing all that it can to be a good neighbor and support the Puna community. | Photo:

“We had protestors in the beginning when we first opened,” Kaleikini recalls, “but, thankfully, nothing like what happened with other projects.”

He says PGV performs regular community outreach so Puna residents understand what’s happening in their backyard and have a chance to discuss it.

Guy Toyama, chair of the Hawaii County Mayor’s Energy Advisory Commission, describes geothermal’s initial appearances in Hawaii as a “disaster.”

“There was no input from the public and it was an open system, so the hydrogen sulfide was let go into the atmosphere,” he recalls. “When PGV came along, considering the history of geothermal, they came across many challenges.”

Toyama says PGV’s closed-loop, zero-emission system is much safer and cleaner than previous technologies.

“I’m sure that’s one of the reasons the public is more accepting of PGV’s operation,” he says. “This time around, the feeling in the community is different.”

Geothermal today

With its natural resources, the Big Island could be a huge power supplier for the rest of the state. Already, about 30 percent of the Island’s electricity comes from renewable resources and there is the potential for much more. Richard Ha, president of Hamakua Springs Country Farm, sees geothermal as an economic engine that could not only create cheaper energy, but also cheaper production, manufacturing, agriculture and transportation.

“Geothermal could create a new industry for Hawaii Island rather than just creating jobs through resort development and luxury subdivisions,” he says.

Kaleikini notes that, every year, PGV spends millions of dollars on labor, taxes, maintenance and community contributions. PGV’s energy also replaces about 150,000 barrels of imported oil that would otherwise be needed to generate electricity. PGV is negotiating with HELCO for an 8-megawatt expansion (about a 25 percent increase) and both parties expect an agreement by the end of the year.

HELCO President Jay Ignacio says PGV’s latest technology will allow the utility to control how much energy goes into the grid, which will improve its total system management. Currently, there is no on/off switch, so 100 percent of PGV’s power goes directly into the grid.

Geothermal is considered a firm renewable source of energy, as opposed to wind and solar, which are intermittent sources. But the wells are difficult to sustain. Last year, production at PGV declined by 30 to 40 percent because of a few clogged wells, Toyama says, which leaves fossil fuel-burning plants as still the most reliable source of power.

“It’s important for us to build our clean energy portfolio to spread out the risk,” Toyama says. “When it comes to geothermal, it’s not a resource problem, it’s a technological and investment problem that we face.”

PGV’s current contract with HELCO is based on the price of oil – the price HELCO pays goes up or down as oil prices do. But future contracts will not be tied to oil prices.

“So, if oil prices go up and stay at a high level, then geothermal becomes more attractive and would stabilize the price of electricity,” Ignacio says.

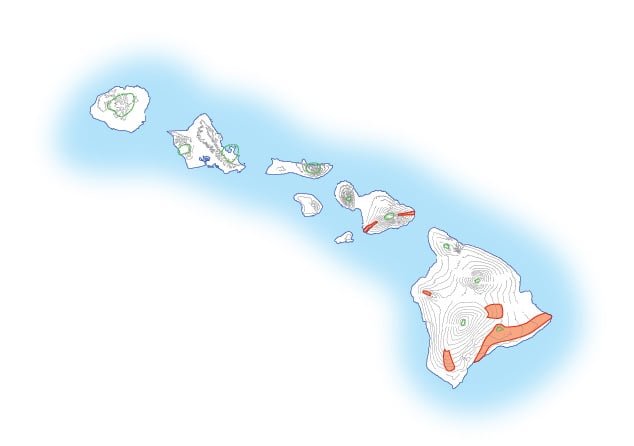

Hawaii’s Geothermal Hotspots, Red = High-temperature resource areas and Green = Lower-temperature resource areas | Source: State Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism

Show me the money

Unlike the open ocean, where catching fish is a free-for-all, geothermal steam is considered a mineral owned by the state. That means PGV pays the Kapoho Land Partnership to lease its land and also pays the state royalties based on annual sales. Kaleikini says PGV typically pays about $2 million to $3 million a year in royalties – about 10 percent of the company’s revenue. Of that, the state takes 50 percent, Hawaii County gets 30 percent and 20 percent goes to the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Over the years, questions have been raised about how the royalties are spent.

According to Russell Tsuji, deputy director of the Department of Land and Natural Resources, revenue from geothermal is not spent on any specific programs. Instead, the money goes to the Special Land and Development Fund and helps pay expenses for the Land Division, which administers leases and manages all state-owned lands. The revenue also funds other DLNR divisions.

For the past couple of years, state royalty revenue from PGV has declined, Tsuji says. It was up to $1 million a year when the price of oil peaked.

OHA CEO Clyde Namuo says PGV royalties help pay for OHA grants, services and projects in the community, as well as OHA’s operating costs.

Trask says more of PGV’s royalties should be used to directly benefit Puna residents, who have accommodated geothermal for years.

Only the county’s share of the royalties goes exclusively for public-benefit projects in Puna. County Councilwoman Emily Naeole-Beason, who represents the area, has shepherded royalty funds to upgrade the Pahoa garbage transfer station, install streetlights, pave roads, purchase two public transit buses for the area and repair the community swimming pool.

“Whatever the county gets from royalties, we put it back into Puna,” Kenoi says.

PGV also contributes $50,000 a year to a fund that compensates Puna residents adversely affected by geothermal development. Kaleikini says the fund has accumulated about $2 million and, to date, paid only a few claims and a few thousand dollars to relocate neighbors of the plant.

Every year, PGV also donates scholarships for graduating seniors from Pahoa High School and offers a summer-hire program.

Robbie Cabral, founder and chairperson of Innovations Development Group – a local company that says it tries to protect indigenous communities from exploitative developments that violate human rights – says implementing a few programs and contributing a couple of million dollars into a fund isn’t enough.

Others, such as Ha, Toyama and Kenoi, see it differently. They believe PGV has been a good neighbor, given back to the community and communicated well with residents.

For PGV’s first 10 years, while oil prices were lower than today, the company was in the red, Kaleikini contends. “It wasn’t until recently that we’ve been doing well enough to help out more in the community,” he says.

Cabral isn’t buying it: “What they’re telling you is the tip of the surface and unless you’re familiar with their financial model, which speaks to actual costs to run this whole thing, you will see that within the net present value of this transaction, there is enough room to give the community a piece of the action. … They’re holding out!”

A new model

Cabral and Trask, who is also an advisor for IDG, say they’ve engineered a better business model for geothermal development that encourages community partnerships and benefit sharing. IDG says it has worked with the Maori in New Zealand to structure similar agreements.

The Native-to-Native Trade model goes beyond looking at who is the shareholder and who is the stakeholder, Trask says. “It also asks, ‘Who is the right holder?’ ”

In Hawaii, geothermal belongs to the state and the people, she continues. “We have never seen a development model that respected that and provided for a fair sharing of benefits.”

Cabral says what’s needed is equitylike compensation, or returns, to the community, which is benefit sharing through a percentage of the cash flow after all costs and risks are assessed. She also suggests that developers set up a community trust that would be governed by indigenous people.

“They would also be able to make recommendations – not direct policies – to the corporation on all issues.”

N2N’s advocates say it also provides for the protection of cultural heritage, prudent management of the resource and responsible stewardship of the land. Additionally, developers would pledge from the start to give part of their profits directly to the community. “They should be saying, ‘You help us and allow us to do this, and we’ll give you a share of the business,’” Cabral says. “Without community support, you have 100 percent of nothing. If I were the community, I would be saying, ‘Hey, what’s in it for us? Why would we want to take the risks knowing what this industry could do to our aina unless we are a part of the decision-making in some capacity or we are a part of the profitability?’ ”

Hawaii Island spends $1 billion a year on imported oil

Geothermal expansion

Last legislative session, Senate Concurrent Resolution 99 called for the creation of a geothermal working group to evaluate the potential for new geothermal development and to research the viability that geothermal could serve as the primary energy source for electricity in Hawaii County. The 10-member group, made up of Big Island leaders – from cultural groups, business, HELCO, government and others – will provide an interim report to the Legislature by the end of the year and a full report next year.

Ha, who co-chairs the geothermal working group, says he looks forward to learning more about the N2N model.

Trask says the group is a step in the right direction. “For the first time, I see that there is a place for us.”

The world’s richest geothermal areas include Iceland, New Zealand, California, Portugal and Mexico – basically, anyplace with a volcano has potential. Although PGV likely could generate enough geothermal electricity to power the entire Big Island – about 200 megawatts at peak – it would be more efficient to develop a second plant in Kona, near much of the island’s development and population.

“It sounds good to us, but you need the market before you can expand,” Kaleikini says. Over the past several years, energy consumption has declined as the price of oil and power has increased and people have conserved more.

Another challenge is that geothermal needs lots of capital investment up front; Kaleikini says an oil plant can be built for 20 percent less than a geothermal facility that generates the same power.

HELCO’s Ignacio says the utility or a single developer alone will not make geothermal expansion happen. “I think it’s going to be a partnership between the utility, government, developer and being sure that we involve the community,” he says. “It’s probably going to have to be some kind of shared-risk structure.”

The same cost-sharing would likely apply to a related project that’s been discussed for decades: an undersea cable that would transport geothermal energy between islands. The state is currently studying the feasibility of an undersea cable that would connect Oahu – the state’s largest consumer of energy – to wind farms on Molokai and Lanai. The next phase of the study is to look at the viability of adding Maui and then the Big Island to that network.

Ha says the sticking point is the cable’s cost. That tab, probably in the billions of dollars, would likely be split among state taxpayers, utility customers and whatever federal assistance Hawaii could get.

Kaleikini understands that he and PGV are under the microscope because of the failed geothermal developments that started it all. But, he says, he is committed to using geothermal safely and responsibly for the benefit of the people of Hawaii.

“It’s very important for us to do things right,” Kaleikini says. “We think that means outreach, engaging the community, engaging the people who have concerns with the development of the geothermal resource and giving everybody the opportunity to talk about it. It doesn’t matter if it’s us or another developer, if we screw up, it’s going to be tough for someone else to try to come in because people will remember all the negatives. We know this is our shot to prove to everybody that geothermal is the key to our clean energy future.”

Alternate uses of geothermal

Geothermal expansion in Hawaii can’t happen unless some-one’s willing to buy the power, and, as it is, HELCO doesn’t need any more power. PGV is only generating half of its permitted 60 megawatts of energy.

But that opens up the possibility of using geothermal to create fertilizer and transportation fuel, says Guy Toyama, chair of the Hawaii County Mayor’s Energy Advisory Commission. Geothermal energy can also create hydrogen, which can be stored in tanks like propane, and shipped to Oahu for fuel.

In the N2N model, the native resource owners are not only partners with the developer, they have rights to the byproducts – steam and fluid – for ancillary development.

“In New Zealand, we’re looking at capturing steam for hot-house agriculture, using the fluid for the health and wellness industry, which is booming for spas, and using geothermal for tourism-related purposes,” Mililani Trask says. “These ancillary uses allow businesses to grow around geothermal.” This benefit, she says, would apply to everyone in the community.

“Ancillary development in Puna wasn’t considered and, as a result, we see energy from Puna go into the grid, but we haven’t seen a benefit to small-business development there,” Trask says.