Fixing a Broken Budget Process

A fiscal crisis this past fall, coming on the heels of the Wonder Blunder and other missteps, is forcing UH and its flagship Manoa campus to reform its flawed budget process.

For decades, UH allocated funding to individual departments and programs using a “historical” method: Each department got a budget based on what it was allocated the previous year. Those familiar with UH’s budget history say that system got the job done until funding was cut by the state Legislature and other sources in the 2008-9 recession.

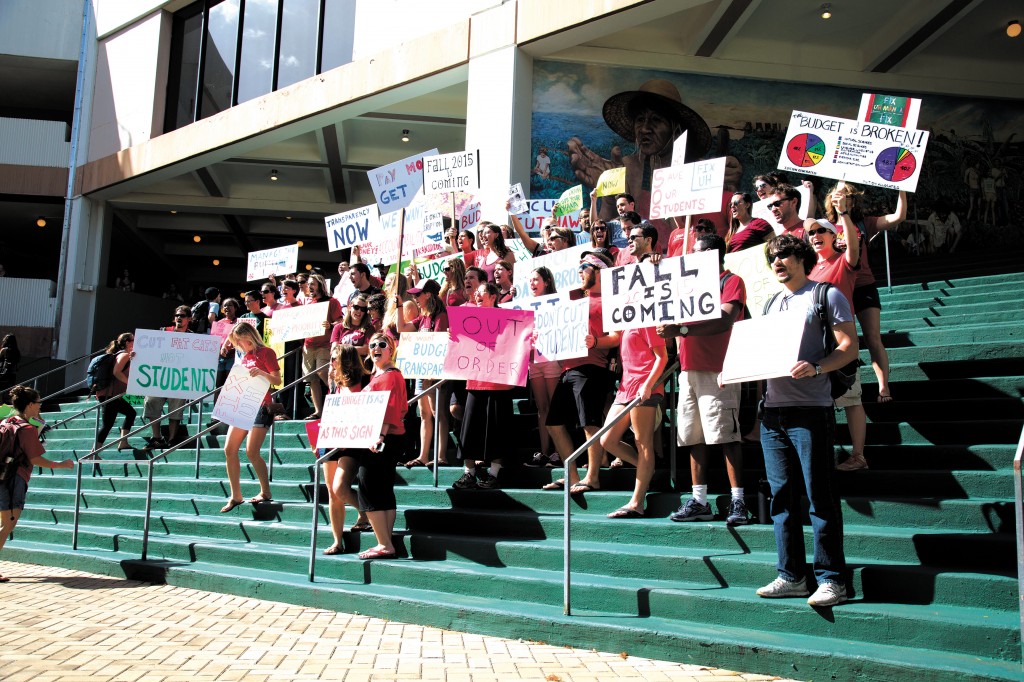

Afterward, UH-Manoa’s budgeting limped along for a few years, then really broke down in the summer and fall of 2014, forcing administrators to cut courses and let go of instructors for the following semester. Students, parents, faculty and lawmakers were outraged, and UH-Manoa Chancellor Tom Apple was fired. Now, for the first time, Manoa is trying to create a budget formula for the entire campus that will determine how programs are funded for years to come, administrators say. The challenge is figuring out a formula to fund the campus’ dozens of programs, each of which is unique, while measuring each program’s performance and productivity.

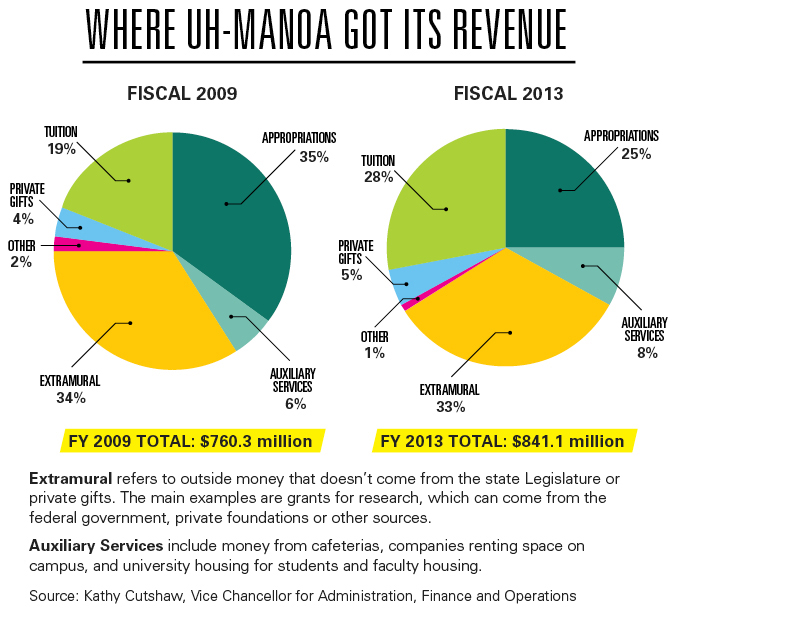

UH-Manoa’s operating revenue during the 2013 fiscal year totaled just over $841 million. However, more than 60 percent was already allocated for a specific use, such as federal grants for medical and other research, private gifts to fund scholarships and student fees for specific purposes.

The remaining 40 percent, about $330 million, comes from student tuition and “general funds,” primarily money allocated to the university in biennial budgets by the state Legislature.

“The regular tuition is the only one we’re looking at in terms of a different distribution model,” says Kathy Cutshaw, Manoa’s vice chancellor for administration, finance and operations. Since last fall, Cutshaw has led a committee charged with developing proposals for a budget formula for UH’s flagship campus.

State funding was cut by nearly one-third in the 2010 fiscal year, while tuition revenue has increased 27 percent since fiscal 2009. In 2009, tuition was only 19 percent of Manoa’s revenue; today it accounts for 28 percent.

Former Chancellor Tom Apple says the historical method of budgeting worked in the past because there was more money from the Legislature. “It works fine as long as the resources are there,” Apple says.

Tom Apple was fired as UH-Manoa’s chancellor in July as the budget crisis deepened. He says the university has been forced to change its budget process because of years of reduced financial support from the state Legislature. Photo: Courtesy of Ka Leo o Hawaii

What saved Manoa in the first years after state funding was cut was its savings: The campus drew on a reserve fund to keep itself running. But Manoa didn’t revise its budgeting method to reflect the decreased funding. “There was an almost 30 percent cut in support from the Legislature, and the university never made a single change in the allocation model,” Apple says.

Paying the Price

Faculty say the current budget method has made it hard to address student needs.

Marguerite Butler is an assistant professor in Manoa’s biology department who is active in I Mua Manoa, a group of students, faculty and others who participated in last fall’s protests. She says the current method of budgeting hinders her department’s ability to hire graduate students as teaching assistants (TAs often teach undergraduate classes or support professors who teach large classes). Even when the money is there, not receiving a final number until just before the school year begins means UH’s offers come after those from other universities. “We don’t know how many instructors we can hire, we don’t know how many graduate students we can hire,” she says. “By the time UH offers, many have accepted [positions] elsewhere.”

The model isn’t responsive to the needs of undergraduate students, either. Students regularly sign up for classes months before the semester begins; yet, with funding uncertain until just weeks before the first day of classes, many departments choose to plan their offerings conservatively, limiting courses and sections according to a worst-case budget scenario.

Denise Konan, a former interim chancellor who is currently the dean of Manoa’s College of Social Sciences, says faculty in her college plan using several possible budgets because they don’t have a firm figure. She says many colleges don’t receive a final budget for a semester until the term is half over.

Another problem faculty cite with the historical approach is the lack of a connection between a department’s budget and its costs, such as the number of majors or course enrollments. Although the number of majors a department has or the number of students it teaches ebbs and flows each semester, funding doesn’t change with those measures. “The current system operates rather automatically as allocations don’t change too much from year to year,” Konan says.

That creates a system without incentive for growth or change, Butler says. “If you don’t get any more money, you’ll basically be burdened by your success,” she says. “It’s not possible to make more money by increasing enrollment. You either limit majors or you drastically reduce the services offered.”

Finding a solution

Designing a system that responds to growth or contractions in individual units poses a unique problem for UH, says Vance Roley, dean of the Shidler College of Business.

Unlike those at other public research universities, most of UH-Manoa’s colleges focus on either teaching or on research. An example of the contrast, he says, is the difference between the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, which has relatively few students but brings in millions of dollars in grants, while the College of Arts and Sciences doesn’t attract as much research money, but serves thousands more students, particularly undergraduates.

Roley says that, at other universities, the divide between research and teaching is less extreme. The challenge for Manoa is creating a budget method that works for both. “How do you design a formula that rewards the research units and at the same time relieves the pain of those of us who are doing the instruction work?” he asks.

There are also a variety of ways to measure each department’s productivity. Units focused on teaching, for example, can be evaluated according to the number of students they graduate or the number of credit hours they teach each semester.

In their search for a formula that works for UH-Manoa, vice chancellor Cutshaw says the committee is evaluating multiple models and how they work at different universities around the country. Many of the models take the productivity of individual units into account, she says, but the degree to which each does this varies.

One model, called Responsibility Center Management (RCM), involves dividing the revenue and expenses of a university according to the specific unit – often the college – where they originate. Services not associated with any one college, such as the library or administration, are divided among each of the colleges, which are then responsible for covering their share of the expenses with the revenue the college generates.

Another type of budget, called the Activities-based model, also makes colleges responsible for their own costs, but pays for the services not associated with any one college out of a central budget. It differs from RCM, since the university doesn’t have to track the common services a college uses as closely. “We don’t have to say, ‘How much is the dance department using the library?’ ” Konan says.

While he was provost at the University of Delaware, Apple says, that university used an RCM model. “You earn your money by teaching or doing research and pay for the resources you consume,” he says, adding that colleges at UD are responsible for every one of their costs, including electricity.

In studying these models, the committee is looking at case studies from other high-enrollment public colleges, such as the University of Michigan and the University of Washington, which have already implemented these models, Konan says.

Another example of a productivity-oriented budget can be found within Manoa. Outreach College, which operates a variety of courses outside of the traditional daytime school year offerings, including summer courses and noncredit programs for the general public, already uses formulas to divide its revenue. Under the model used for summer school revenue, for example, 67 percent of the tuition goes to the college offering the course, 30 percent to Outreach College and 3 percent covers administrative costs, Cutshaw says.

For those courses, Konan says, the model gives colleges and departments much more control over what they earn. “We’ve seen great success with how chairs are able to track revenues they receive from the Outreach College,” she says. “I believe they will likewise adjust very quickly to a new model where budgets rely on activities.”

For those courses, Konan says, the model gives colleges and departments much more control over what they earn. “We’ve seen great success with how chairs are able to track revenues they receive from the Outreach College,” she says. “I believe they will likewise adjust very quickly to a new model where budgets rely on activities.”

Finding New Funding

Providing accountability for specific expenses isn’t the only issue to tackle, according to Apple. When possible, colleges must find alternate funding to free general and tuition money for other uses.

One way mainland universities do this, he says, is by requiring their research faculty to write all or part of their salaries into grant applications. Although that leaves fewer dollars for research, Apple says, it’s a common practice among most other research institutions. “Program managers at the [National Science Foundation] are surprised that our faculty aren’t putting their salaries in their grants,” he says.

Apple lobbied for both electricity accountability and research salaries to be included in grants while he was chancellor. He says he doesn’t know whether either is a priority for the new chancellor, Robert Bley-Vroman. Bley-Vroman did not comment by press time.

Regardless of how the campus rearranges its budget, Konan says, funding will likely remain an issue in the short term. “Next [school] year, things will continue to be tight for us at the colleges.”

Budget problems and a semester of unrest forced Manoa to have a discussion about its finances, Konan says. “That gives me hope, because we can make changes in times like these that we might not normally be able to make. The fact that we’re even talking about the budget model is huge.”

What’s the Legislature’s Perspective?

State Sen. Brian Taniguchi, a Democrat who chairs the Senate’s committee on higher education and has been in elected office for 35 years, says support for higher education is at a low point in both houses of the state Legislature. He points to scandals, such as UH’s loss of $200,000 in an attempt to book pop singer Stevie Wonder for a fundraiser concert in 2012, that have eroded the Legislature’s confidence in the university.

At the end of 2014, a state audit chided the university for failing to report on some special funds and accounts and for using others for things other than their intended functions. The audit also raised questions about UH’s ability to manage its own finances.

That critique, Taniguchi says, creates a challenge for UH officials lobbying to increase state funding for the university. “The Legislature as a whole has not committed to higher education,” he says.

Although the Legislature can appropriate money for specific uses at UH, such as a new program or building, it does not have the authority to decide as much of the university’s budget as it did before the mid-1990s. Before then, all allocatable revenue the university generated – including tuition – was given to the Legislature, which then decided how much money to give to the university.

Even so, state Rep. Isaac Choy, who chairs the state House’s committee on higher education, says he will monitor how the university evaluates any budget formula it implements.

Choy, who is also a certified public accountant, says the university and the state shouldn’t wait until the end of the first fiscal year to evaluate the budget model. He points to other states, such as Missouri, which maintain real-time online records of how public money is spent by state-funded agencies, including the university system.

The need to evaluate the formula as it is implemented is crucial because of the multiple factors the Manoa chancellor’s committee is considering integrating, he says. “That’s got to be the most complicated thing in the world,” he says of developing a formula.

Writer Alex Bitter, a former intern at Hawaii Business, is the editor in chief of Ka Leo O Hawaii, the student newspaper at UH-Manoa.