Hawaii Farming’s Uncertain Future

Hawaii’s farmers can’t catch a break.

Rat lungworm has accelerated difficult changes in local farming. One local leader predicts a quarter of Hawaii’s produce farms will be out of business in a few years.

They are already battered by high land and energy costs, intense competition from Mainland imports and their own advancing age. Now there’s another threat to their survival: rat lungworm, a disease that arrived in the state more than 50 years ago, has roared to new life.

“We’ll have a loss of farms,” says Scott Enright, director of the state Department of Agriculture. Over the next few years, he says, the disease could cripple many of the state’s 3,860 produce farmers, who will face more regulatory oversight, more costs and more concerns from consumers about whether their crops harbor the tiny snails and slugs that carry the dangerous parasite.

“My expectation is that this is going to be a hurdle that a number of farms aren’t going to be able to traverse,” Enright says. “Between 20 and 30 percent of our (produce) farms will go out of business.”

The immediate concern is the health of consumers, but the long-range question is the viability of local farming and the goal of greater food security for Hawaii. Many farmers face new federal food safety rules as a result of the Food Safety Modernization Act, and this latest outbreak has already brought more scrutiny.

“The food safety trend is going to cover everybody in the near term, within three to five years,” Enright says. “And liability insurance is going to push all the farmers to adhere to food safety. Eventually, insurers won’t write liability policies if they (distributors) can’t verify to the insurer that they’re acquiring food that adheres to food safety guidelines.

“As unfortunate as rat lungworm is, it has put a spotlight on food safety issues. And farmers who were pushing back against additional regulations for agriculture realize now there’s no way to get around it. It’s a long-standing trend we need to deal with. In five to seven years we will start to see all the fallout in the farms.”

Hawaii had only one rat lungworm case in 2014, but nine in 2015, 22 last year and 17 new cases this year by press time. Farmers have lost sales and contracts — even those farmers who have not sold tainted produce — though it’s difficult to quantify exact losses. This year, Hawaii Island has had 10 cases, Maui six and Oahu one.

UH Maui Cooperative Extension educator Lynn Nakamura-Tengan says the economic impact is being felt.

“Growers took a significant hit,” says Nakamura-Tengan. “Growers on Oahu lost some major accounts (and) buyers are dropping growers because of concern.” Meanwhile, the Whole Foods Market store on Maui announced it would not buy local produce for now.

The lead agencies in the fight against rat lungworm are the state departments of Agriculture and Health, and UH’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. They are supported by other state, county and private agencies, and coordinated by the Governor’s Joint Task Force.

The first line of defense has been educating farmers, local residents and visitors. Farmers are getting information on the appropriate pesticides and their proper use in ridding farms of snails, slugs and rats. If a retailer reports any issue, multidisciplinary teams from the departments of Health and Agriculture immediately inspect farms and then work with the grower to fix problems and keep any tainted produce from reaching market.

“We have every possible partner that can help us with this disease,” says Dr. Virginia Pressler, director of the state Health

Department. “Anyone who has anything to offer is part of the effort.”

Pressler says rat lungworm is endemic in the Islands, the Pacific and parts of Asia; it can be managed, but not eradicated. Like any brain disease, it can devastate individuals and their families, but it should not have a statewide, long-term health care impact, she says.

Dr. Po-Yung Lai, agricultural liaison in the Honolulu Mayor’s Office of Economic Development, says the education of farmers is crucial, especially new ones such as those farming on land the state purchased in Wahiawa.

“The city asked for 200 acres set aside for small farmers and there’s one already farming there, and additional farmers will be coming in by the end of the year,” Lai says. “Lots will be growing leafy vegetables, cucumbers, beans, eggplant, and things like that. Because we have the snail and slug all over the island, all over the state, it behooves them to farm properly.”

Rat Lungworm is caused by a microscopic worm that is eaten and then migrates into a person’s brain. The worm can be ingested from produce that is poorly washed or from tainted food such as snails, freshwater prawns, frogs, crayfish and crabs. The disease can cause severe disability and has killed two people in Hawaii since 2007. For more information from the state Department of Health, go to tinyurl.com/ratlungworminfo.

How Rat Lungworm Got to Hawaii

Rat lungworm disease probably originated in China and came to Hawaii when the Islands began trading with them, says Dr. Kenton Kramer, who heads the governor’s task force that is studying the disease and managing the state’s response. The disease’s presence in Hawaii may even go back to the sandalwood trade of the 19th century, says Kramer, but it wasn’t recognized here as a disease until the 1960s.

UH professor Joseph Alicata and Honolulu physician Dr. Shigeru Horio published a paper in the early 1960s diagnosing the case of a patient who had eaten two slugs under the illusion that they could cleanse the blood.

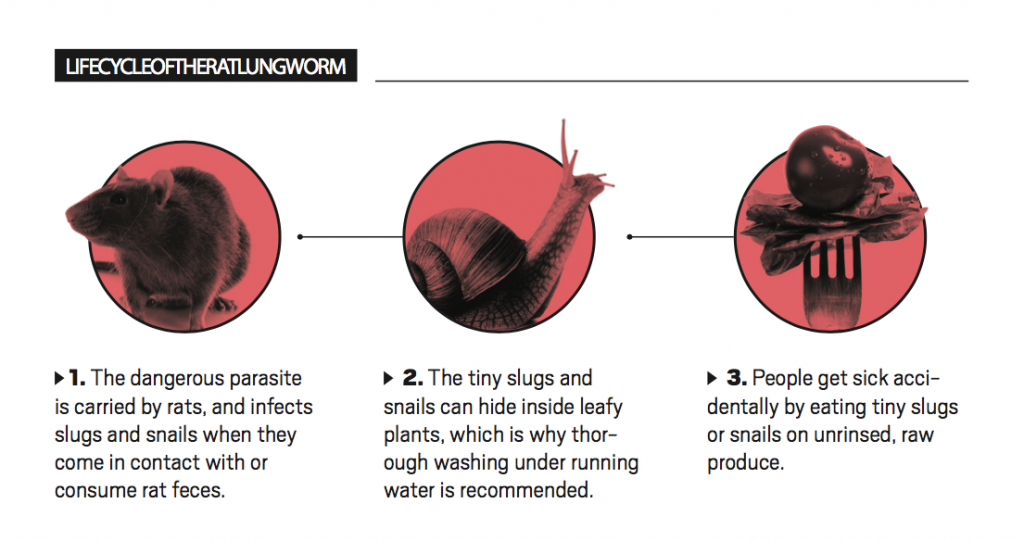

The rat lungworm parasite must live in first a rat and then a slug or snail to complete its life cycle. Slugs and snails ingest it in rat feces.

The disease can be difficult to pinpoint because a true diagnosis requires a spinal tap, said Kramer, and patients sometimes don’t want to undergo that procedure. The disease’s severity is generally determined by how much of the infected food a patient consumes.

People are accidental hosts for the microscopic parasite, which is eventually destroyed by the body’s immune system if the patient survives, says Kramer. A subcommittee of the governor’s task force is studying the best medical treatment for the disease and looking at whether to give patients anti-parasitic drugs. Studies are divided over this treatment, Kramer says.

The committee is also seeking information from sources in Asia, where the disease is more prevalent and more studies have been conducted.

Kramer says that just like commercial farmers, home gardeners also must control pests around their gardens, including rats, slugs and snails.

Educational outreach includes talking to children at schools and shoppers at farmers markets. A slide show plays in a continuous loop at the Interisland terminal baggage claim area of Honolulu’s Daniel K. Inouye International Airport, warning visitors of potential health risks during their stay, and healthy practices such as washing fruits and vegetables thoroughly. One key prong of the outreach campaign is aimed at schools with garden projects; 80 percent of the state’s K-12 schools have gardens, according to a Health Department survey.

Health Department leaders continue to reassure the public that eating local produce is no more risky than eating Mainland greens. They note that all fruits and vegetables should be washed thoroughly before eating, with greens rinsed several times under

running water.

Nakamura-Tengan works on the education campaign with farmers and the public on Maui. When addressing them, she often asks for a show of hands to see how many wash their vegetables. Not all the hands go up.

“I think people forget,” she says. “If it comes in a bag (they think) it doesn’t need to be washed. It’s just a simple thing. I was also asking if they washed their bananas and pineapple, and they say, ‘We don’t eat the peel.’ But you don’t know what goes on the peel. You should be washing all your produce. It doesn’t matter where you’re buying it or where it comes from.” In fact, all produce should be washed, even produce that is peeled, because that will remove other possible contaminants, she says.

The fallout means some small farmers are shifting to other crops not directly impacted by rat lungworm.

“A lot of farmers are adapting,” says Enright. “A lot changed crops. Often they’re not just growing one crop. They might have three. So the farmers just change crops and stop growing the most likely suspect — leafy greens — and start growing a root crop they can continue to sell. I haven’t heard of anyone going out of business yet. They are adapting, which is what agriculture is always about. A rainstorm, a pest, you adapt, and agriculture is doing that right now. We’ll be back growing leafy greens, but we’ll be doing it with food safety protocols in mind.”

Much of the increased scrutiny comes from the federal Food Safety Modernization Act of 2016, which imposes rules based on income, not acreage. Those rules will initially affect 613 of the state’s largest farmers. The bulk of the state’s produce farms, though — about 3,250 — are exempt from those rules based on their small size, the produce they grow or the way they market their produce. The state has a total of more than 7,000 farms of all types.

“It’s tiered, with the largest farms (sales over $500,000 a year) having to be in compliance by this coming January, medium farms (up to $500,000) a year after that and smaller farms (up to $250,000) the year after that,” Enright says.

Growers, especially the largest, will face two types of inspections: certifications done because of these new federal regulations, and audits performed because of the growing demands of buyers. About 150 to 200 local growers have already done the training and received certification for their safety protocols, says Nakamura-Tengan. Training is ongoing for farmers growing produce that is commonly eaten raw.

Rat lungworm controls are not specifically included in the certification training, but extension agents added them, she says. The training costs a grower $150 but is being underwritten by groups such as the Hawaii Farm Bureau and Hawaii Farmers Union United, she says.

Other aspects of the new federal rules will add costs, especially when it comes to tracking produce, says Enright. “Say the distributor buys a case of cabbage from the Big Island and someone in Honolulu gets sick. We’ll be able to trace back that cabbage to place and time and day of harvest.”

Larry Jefts, among the state’s largest farmers, is already doing that. “He has a couple of staff doing food safety because of the requirements of individuals buying from them,” Enright says. “It will require being out in the field with a tablet and inputting data in real time. And it’s part of the reason I will predict farmers being unable or unwilling to do it.”

Currently, says Enright, only the larger farms are doing such record-keeping. “I know of very few farms that are keeping those traceability records. Additionally, the rule calls for monitoring the microbial action in the water they use for irrigation, which is another cost.”

Third-party audits are also becoming a marketing requirement, says Nakamura-Tengan. And they’re much more expensive. Enright agrees.

“Part of food safety compliance is going to be farm audits,” he says. “It definitely increases costs.”

Each audit costs from $1,000 to $3,000, depending on a farm’s complexity, and covers food safety systems. “It will be an additional cost of doing business to continually verify they (farmers) are in compliance,” Enright says.

Farmers who are already undergoing audits will have an advantage, because they can show their safety records over time, says Enright. “They’ll (the audits) show you have consistently done a good job.”

He points out another part of the equation: The average farmer in Hawaii is 60 years old, close to the national average.

“They’re thinking about retirement,” he says. “And with these additional requirements, a number have started to choose to retire. To the extent they own their land, they’re land rich. That’s their retirement account.”

Those retirements are another obstacle to the state’s goal of reducing Hawaii’s dependence on imported produce.

“It may have an impact on sustainability,” says Dr. Kenton Kramer, chairman of the Governor’s Joint Task Force on Rat Lungworm Disease, and an associate professor in the John A. Burns School of Medicine’s Department of Tropical Medicine, Medical Microbiology and Pharmacology.

“Farmers are telling us that people have stopped buying as much produce as they used to,” Kramer says. “Restaurants and larger customers have stopped buying produce. It has forced them (farmers) to rethink what they plant and maybe not plant what isn’t selling.”

Nakamura-Tengan says safety is “a collective agriculture industry issue, but the individual growers need to take individual action to reassure their buyers or maintain their own market.”

“It becomes a one-on-one story although it impacts the whole industry. Individual growers have their relationship and track record with their respective buyers and that relationship can make a difference in their ability to retain a market.”

She encourages farmers to write down a fully developed safety plan, instead of simply having a plan in their heads. That’s the best existing strategy for managing pests in the production areas where produce is cleaned and packed for shipping, she says.

“What they’re doing is making sure there is a clear area in the borders around the production area and monitoring for activity in those areas and then to put down bait to reduce any population,” Nakamura-Tengan says. “Some have been doing their own slug and snail baiting and trapping just to see what kind of activity they have and have responded based on what they find. There’s a zero tolerance for slugs and snails.”

She also recommends increased inspections by the farmers themselves.

“We’re saying they should inspect in as many steps as possible,” says Nakamura-Tengan. “There’s an opportunity to do inspections while they’re doing management such as weeding. If they’re weeding or harvesting and see activity, then they should take appropriate action in terms of keeping it out of the market system. When they’re field packing, or in the packing house, there’s another opportunity for inspection.

“So, depending on the crop, there may be multiple points of inspection to take action. That’s what we’re asking them to do. And I know they’re suitably motivated to reassure their buyers, and keep their market.”

Symptoms

Not everyone will have the same symptoms. They usually start 1 to 3 weeks after infection. Illness can last for 2 to 8 weeks or longer.

Symptoms Include

- Severe ongoing headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Neck and back stiffness

- Tingling or painful skin

- Low-grade fever

- Although rare, coma and death

Children may have behavioral changes such as unusually bad temper, mood changes or extreme tiredness.