Facing Future

“There was always something else. When pineapple closed, the resorts were there. When the ranch closed, Monsanto was still there. There was always an answer. We don’t have the answer now.”

—Kimberly Mikami Svetin, Store owner

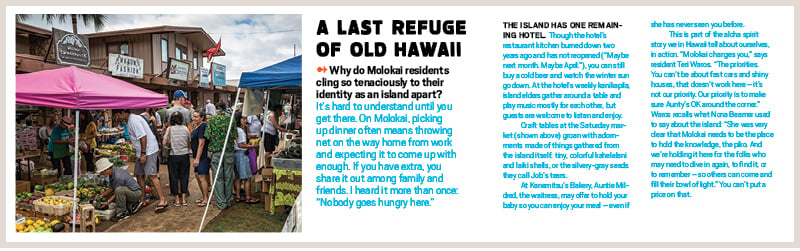

To some people, Monsanto is the face of corporate evil, but David Makaiwi sees a different face. Before Monsanto hired him, he sold drugs, served time and drifted from odd job to odd job.

“They gave me one second chance at life,” Makaiwi says. “I no more one schooling education. Everything I learned in my life is from watching and learning. I fight for this company because I see nothing wrong with it. What happens out there on the mainland and stuff li’dat, I don’t know. But I know what’s happening here on Molokai.”

When Maui County voted in November to place a moratorium on growing genetically modified organisms, like those used by Monsanto and Mycogen, the two big seed companies on Molokai, the overall county voted 50.2 percent in favor of the moratorium. On Molokai, the vote was 63 percent against. One reason is that the seed companies are the biggest private employers on the island, and the only other substantial employers are government and welfare. One in 10 of the 2,200 jobs on Molokai are provided by Monsanto or Mycogen, a subsidiary of Dow AgroChemical. A large proportion of other jobs – from truck drivers to independent farmers – are dependent on those two companies.

Samson Kaahanui lost his job with Molokai Ranch in 2008 but found work with Mycogen. Now, he says, if he loses that job, he’ll do what many did when pineapple packed up or when Molokai Ranch closed: He’ll move to Maui to work, but leave his wife and eight children at his homestead on Molokai, where they can enjoy wide-open space and an extended network of support that wouldn’t be available on any other island.

There is no McDonald’s or other chain restaurant on Molokai, an island with half Oahu’s land mass and 7,350 people, less than half the population of Manoa Valley. Molokai has no stoplights and no rush hour. People drop in unannounced, leave their doors unlocked and answer the telephone with “Aloha.”

“That’s Molokai,” Kimberly Mikami Svetin tells me, with a shrug. It’s part of what drew her back to the island to help run her family’s drugstore and snack shop after nearly two decades on the mainland. Now, her older son attends Molokai High School, which has no science labs and iffy Internet service, but has sent one student to Harvard and another to Duke in the last few years.

“This island is simplified,” says Kawehi Horner, 35, who is raising his four children on the salary he gets from Monsanto. “We don’t have fast food like everybody else. We don’t have malls, but we don’t need them. Because the things we value are each other.”

The price of staying small

Molokai treasures its sense of human scale, its ruralness, its sense of self-sufficiency and belonging, not to outsiders, but to itself. But in a world that is going the other way, urbanizing and consolidating, where small enterprises are routinely either ploughed under or swallowed up by larger ones, Molokai pays a hefty price for staying small.

For one thing, in a small place, small changes move the needle in a big way. Last November, for example, the island went from one veterinarian to zero. “I got a dog with an ear infection and I have no vet to go to,” says Robert Stephenson, the president of the Molokai Chamber of Commerce. Another example: Molokai High, the island’s only high school, has a graduating class that fluctuates between 70 and 120 students, but it is subject to the same weighted student formula as the rest of the state. A small drop in the number of students means the loss of a teacher – and suddenly the number of “career pathways” offered to all the island’s public school students drops from five to three.

Molokai is also too small, population-wise and financially, to be an independent county. The island is part of Maui County, run from the much more populous Maui Island – where an influx of development and new residents has transformed the demographics and priorities in recent decades. “The dynamics here (on Molokai) are so different than anything on Maui, and yet the decisions are made on Maui,” says Stephenson.

In recent years, Hawaii has become what Monsanto’s community affairs manager Dawn Bicoy calls “the funnel” for most of the genetically modified seed corn grown in the United States. And with the rest of the state, Molokai has become part of what’s been called “ground zero” in the war between multinational agrochemical corporations and the worldwide grassroots anti-GMO movement.

Ground zero, as everybody knows, gets blasted. The moratorium passed by the voters of Maui County sets an end date of March 31 on the growing of genetically modified organisms, pending a health and environmental evaluation. Proponents of the bill say evaluation and moratorium will last a year; opponents say at least two years, and possibly forever.

Chris Mebille, who owns and manages Molokai-based Makoa Trucking and Services, says, “I would venture to speculate that 90 percent of those people who voted for the ban have never even been to Molokai. They have no idea of the struggles we have.”

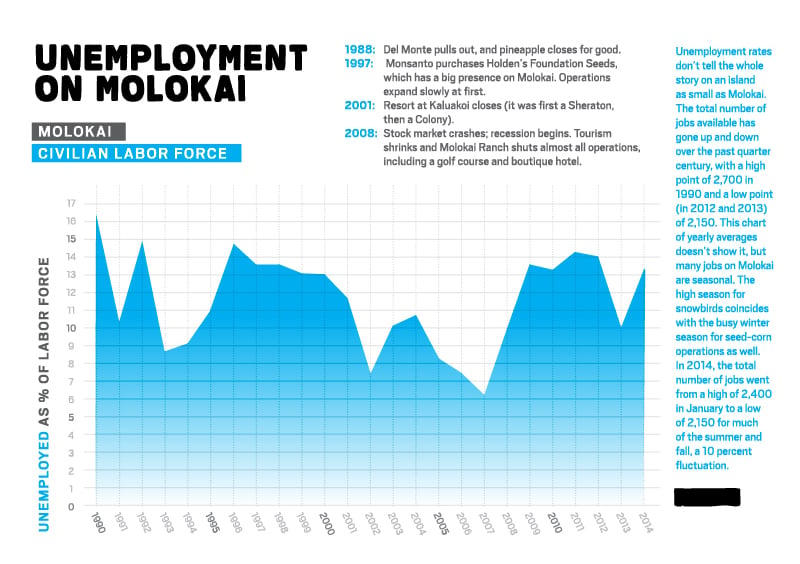

The economic numbers show how Molokai is struggling. In November and December 2014, the unemployment rate wavered between 11 and 14 percent, more than twice that of Maui Island or the state as a whole. But the unemployment rate understates the problem, because it does not count the many people who have stopped looking for work. As of September 2014, 2,564 people, or 35 percent of Molokai’s population, received federal nutrition assistance in the form of EBT cards – and, because Molokai’s unemployment rate has been consistently above 10 percent, it is one of the few places in the nation exempt from the welfare time limit imposed by federal welfare-to-work rules. Many residents worry the exemption has created “generational welfare.”

Ala Malama Avenue, Kaunakakai’s main street, reflects that struggle. Shops that sell food prominently display “We accept EBT” signs. Several storefronts stand vacant; others barely scrape by. One is occupied by the island’s only bookstore, whose owner, Teri Waros, says her business is down 14 percent over the year before. “The stress is horrific,” she admits. “Every month: ‘Can I pay my bills? Can I pay my rent?’ I stood here in November for a while and thought, ‘I don’t know if I can continue to do this.’ ”

The interior of the former upscale boutique hunting lodge, the Lodge at Molokai Ranch, on the western side of Molokai. In 2008, after real estate values plunged nationwide, the ranch, owned by a Singaporean corporation, shuttered the lodge, leaving most of the furnishings inside. The ranch – then the largest private employer on the island – shut all its operations and put more than 120 people out of work. Photo: PF Bentley

Waros, who grew up in Kailua on Oahu and has lived all over the world, is determined to see the year out: “I don’t want to leave. It’s the old-fashioned aloha. I know other places have it, too, but not like here.”

Long, Slow Slide

Molokai hasn’t really been able to catch a break since the 1970s. Kaui Manera, who was born and raised on Molokai, remembers the island’s “heyday” in the 1960s and 1970s, when pineapple was king and the lively community supported, among many other things, two movie theatres, a bowling alley and a Chinese restaurant, the Hop Inn.

Being small, though, the island has only ever had a couple of big players. When pineapple shifted operations to South America, where labor and land were cheap, an upsurge of tourism broke Molokai’s fall. The Sheraton Kaluakoi opened in 1977, bringing with it what Manera recalls as “busloads of Japanese tourists,” more flights, and “local packages so that the Maui, Oahu, outer island people had deals to come to Molokai and stay at the resort.”

When the resort closed in 2001, there was still Molokai Ranch, which had been a dominant presence on the island for more than a century. The ranch owned the western third of the island, almost 60,000 acres, and ran a cattle operation headed up by Old Man Cooke, who spoke Hawaiian. Then the ranch itself passed out of Hawaii ownership and, as Manera describes it, the “cultural connection waned over the years.” Today, it’s owned by GuocoLeisure Ltd., a Singapore-based company run by one of Malaysia’s wealthiest men.

In 2008, GuocoLeisure announced its plans to “mothball” the ranch and abruptly shuttered operations: the hotel, golf course, most of its ranching and even the town of Maunaloa’s movie theater and gas station, shedding 120 employees in the process.

Though the closing of Molokai Ranch was interpreted by many on the island as an act of revenge for activist resistance to a planned luxury residential development, more likely, says Stacy Crivello, Molokai’s councilmember for Maui County, it was the market crash of 2008, which slashed real estate prices by almost half and made land-banking a more attractive option. Then there is the diagnosis of Todd Ragsdale, a ukulele maker I met at the Kaunakakai Saturday market: distance and indifference. “They don’t care, because they’re in Malaysia. We’re a write-off for them, but their decisions affect 6,000 people. It’s a global world, now.”

The decline has been slow, but the impact over time has been immense. In 1990, 103,477 visitors came to Molokai. By 2014, that number had withered to 59,132 – a plunge of 43 percent.

New business and tourism on Molokai are not helped by a reputation for rejecting every economic opportunity that comes its way, from wind farms to luxury homes to cruise ships – often dramatically. Economist Paul Brewbaker, whose father, Jim, helped introduce the seed-corn industry to Molokai, jokingly called it “the un-Friendly Isle,” a sentiment echoed widely among non-Molokai residents.

Residents say the reputation is undeserved, coming in part from a handful of vocal activists who have more influence outside of Molokai than on it, and also from an island-wide understanding that not everyone who comes knocking is interested in preserving what their community loves about itself. They point to the dramatic changes wrought on other islands as examples of what they don’t want. Waros, who was the general manager of the Lodge at Molokai Ranch before it shut down, says, “Look at Lanai. Molokai people don’t want to live like that, with the uber, uber wealthy, and everybody else makes minimum wage to serve them.”

Residents say the reputation is undeserved, coming in part from a handful of vocal activists who have more influence outside of Molokai than on it, and also from an island-wide understanding that not everyone who comes knocking is interested in preserving what their community loves about itself. They point to the dramatic changes wrought on other islands as examples of what they don’t want. Waros, who was the general manager of the Lodge at Molokai Ranch before it shut down, says, “Look at Lanai. Molokai people don’t want to live like that, with the uber, uber wealthy, and everybody else makes minimum wage to serve them.”

“We don’t want another Waikiki,” agrees Ray Miller, principal broker of Friendly Isle Realty, who has lived on Molokai since 1957, “but I’d like to see us have more jobs for our people.”

What Next?

Some feel the moratorium will be overturned in court, as has been done on Kauai and Hawaii Island with similar measures, with the ultimate responsibility for regulation passed back to the state. Others think the companies should transition to traditional seed corn. Mark Sheehan, a spokesman for the Shaka Movement, which spearheaded the moratorium campaign, said the companies had “switched to traditional seed crops” in other places where growing GMOs had been banned, but couldn’t recall where. Councilmember Crivello had another prediction for what would happen if the moratorium went through: “They’ll pack up and leave! (Non-GMO farming) is not their business.”

Stephenson, the head of chamber of commerce, agrees: “Could the seed industry change its business practices? Of course, anybody can change their business practices. But the market demands (for conventional crops) are already being met. These jobs are in jeopardy.”

When Molokai Ranch closed its operations, one casualty was the island’s only movie theater, in the upcountry town of Maunaloa. Photo: PF Bentley

If the seed companies pulled out, how quick would the transition be? A worker for one of the companies, who didn’t want to be named, observed that, while pineapple was a three-year crop, giving employees plenty of time to find other jobs after the last planting occurred, corn matures in 100 days.

Svetin says it feels in some ways like Molokai is at the end of a line. “There was always something else. When pineapple closed, the resorts were there. When the ranch closed, Monsanto was still there. There was always an answer. We don’t have the answer now.”

Brutal Economics

What can we expect if Monsanto and Mycogen Seeds decamp from Molokai? In some ways, the math is simple, and devastating. Together, Monsanto and Mycogen estimate they pour $15 to 18 million into the island’s economy each year, a number that dwarfs the $6.9 million used yearly by holders of EBT cards.

Miller fears that, on Molokai, “next to the state, welfare would become the next highest employer.” The island’s unemployment rate is already the state’s highest. If Molokai’s total labor force remains at December 2014 numbers, the total number of unemployed would rise from 300 to 520, for a staggeringly high island-wide unemployment rate of 21.2 percent. Some of those let go would look for jobs on-island, says Bicoy, of Monsanto, but, “If you look at the reality of the numbers, there’s no way we could all find different positions.”

Several of the workers I spoke to were planning a move if they were laid off, but Monsanto’s workforce is more than 60 percent Native Hawaiian, and many have large families who live on homestead land. They plan to move to find work but leave their families behind, an option taken by many when pineapple, the resort and the ranch closed. Horner, of Monsanto, doesn’t want to see that happen. “I saw families start to split up because the burden must have been big in the family,” he says. “One would leave, the other would stay home with the kids, but it didn’t work out.”

And not all jobs are created equal. The seed companies pay, on average, wages that are 34 percent higher than state averages for similar positions.

Horner says the effects of a shutdown wouldn’t stop at seed company employees and their families: “It’s going to ripple through everybody else on this island.” Both seed companies say they have made a “conscious commitment” to support local businesses. Chris Mebille, who owns Makoa Trucking, estimates that 30 to 35 percent of his business comes directly from the seed companies, which keep a flow of farm inputs and equipment moving back and forth between Molokai and the mainland. “Three to five of my seven employees would lose their jobs,” says Mebille. “I wouldn’t have the volume to support them.” The story is the same all over town. Ed Wond, owner of Molokai’s NAPA auto parts store, says that 20 to 25 percent of his business comes from the seed companies.

Tina Tamanaha, manager at Hikiola, the island’s farming cooperative, says the seed companies make up more than 30 percent of Hikiola’s business, and provide the financial clout and buying power that helps all 102 farmers she represents. “We only survive through volume,” says Tamanaha, who says that costs for Molokai farmers would rise precipitously if the seed companies weren’t there. She says the smallest farmers would be the most affected.

“If we can’t bring in regular containers, it’s a special order and the cost goes up,” agrees Andrew Arce, who works for Mycogen but also farms 7 acres with his wife, Kuulei. Arce says the Molokai Irrigation System would be another casualty of the moratorium. Although it is used by all the Island’s farmers, the system’s equipment and upkeep are largely paid for by the seed companies.

Arce also thinks a sudden leap in unemployment, in a culture where many people hunt and fish for their food, would also affect the environment. Seafood gets scarce in June, when everyone is collecting for graduation luaus. “Everybody talks about trying to protect our resources,” says Arce, “but if you have another 250 families (depending on) hunting and fishing, how long would those resources last?”

Tamanaha says that, as the moratorium deadline approaches, “I think even people who voted ‘Yes’ (to the moratorium) are changing their minds. It’s like, ‘What did we do?’ ”

Who Will Dig the Hole?

Money and jobs are only half the equation. At first, I found it puzzling that a traditional, rural community like Molokai would embrace two biotech giants that are reviled around the world (last year Monsanto was described by Modern Farmer magazine, tongue in cheek, as “the face of corporate evil”). It couldn’t just be about money or job security. Molokai has said no to many other things that looked like chances to cash in.

I got my answer when I drove past the sign at the island’s only high school. It says: “Molokai High School, Home of the Farmers.” I called their principal, Stan Hao, who confirmed that the school’s motto is “Farmers of Land and Sea.” Its sports teams are all called The Farmers, and the gym is The Barn, even when The Molokai Dispatch writes about it. Molokai wants, most of all, to grow but still remain itself, and that “self,” for the vast majority of residents, tends the land and extends a gracious hospitality. It does not serve mai tais poolside for tips. “I’m from Iowa,” says Monsanto employee Josh Hunziker. “That’s farm country. But I had to come all the way out here to find a team called The Farmers.”

There used to be plenty of farmers. In 1900, nearly 50 percent of Americans worked in agriculture. Today, farming families make up just 2 percent of the population. Even within Hawaii, Molokai feels misunderstood: 92 percent of Hawaii’s population lives in an urban area, with urban concerns and a basic ignorance of how much work it takes to grow the food that goes on your table. People who understand that – be they Monsanto employees or organic purists – tend to stick together.

Walk Monsanto’s fields, and they don’t look like ground zero for anything. In the vastness of Molokai’s landscape, there’s not all that much corn to be seen. Because of water limitations and the stringent distance requirements between individual fields to keep genetic lines pure, only 500 of the farm’s 1,535 tillable acres are planted with seed corn; the rest, though managed for soil conservation, is left green and wild. A few butterflies and bees flit through the windbreaks, planted partly with native species. In one field, a massive mechanical corn harvester sits, inscribed in curling script with the name “Baby’s Baby,” a tribute to the long-time employee who used to drive it.

It looks like a piece of military equipment, but this is “Baby’s Baby,” Monsanto’s whole-ear corn harvester on Molokai. Every piece of large equipment is christened with a name. Most are in the Hawaiian language, reflecting the high proportion of Native Hawaiian employees. However, the name Baby’s Baby honors a previous operator of this vehicle. Photo: PF Bentley

On Molokai, as in other places, people trust their direct experiences – and, in contrast to Molokai Ranch and other powerful offshore presences that are either incommunicative or actively exert pressure to change the culture, the managers and employees of Monsanto and Mycogen feel to many on the island like farm folk. Even those with no financial ties to the companies will say it. Clare Seeger Mawae, owner of a tour and sports-gear-rental company, says that in her personal life, “I’m an organic person. I will choose organic over other products. But my experience of Monsanto on this island is that they have been very community-oriented. I don’t see them as an evil corporation. What I have seen is a lot of loving, caring folks that put their hearts and souls into this community.”

That’s partly company policy – it’s called in-kind contributions – and partly the way things are just done in any farming community, and on Molokai. The point is, they align. Monsanto workers, using company equipment, helped rehabilitate the track for Molokai High School. Mycogen laid irrigation for the school’s farm. Both companies donate sweetcorn for school fundraisers. Ray Foster, site manager for Monsanto on Molokai, is clearly pleased when he describes what the company does for the community: “We’ve got 120 employees, and they’re all out there humming along on the farm, but Akaula (School) needs chairs and tables for their fundraiser. We can go help with that. Or the boys go out and they take care of the Maunaloa cemetery with their weed-eaters. Or the high school needs help with fencing for a big game. We have the tractors, we have the people. There’s really very little incremental cost to the business. That’s just what rural communities do, right?”

Some corn plants are bagged so their pollen can be hand pollinated to other plants. Photo: PF Bentley

Farmers told me about new fields cleared for them by seed company workers who had been given the go-ahead by their site managers – all they had to do was ask. Adolph Helm, project site manager for Mycogen, confirmed it: “Farmers tend to let other farmers know that if they come to us and need help for land prep, we’ll come in and prep the land, bring in our rippers, and get it ready to farm. That saves them four (or) five thousand dollars.” Helm continues, “I think any rural community where farmers play a role, it’s automatic. That’s who we are; it doesn’t matter whether you’re an organic farmer or what. It’s just helping farmers. All farmers.”

The seed companies and their employees have become so intertwined in Molokai’s daily life that they sometimes end up participating in the most intimate of ceremonies, says Manera, who works at the Molokai office of the nonprofit Alu Like. Unlike in Honolulu, where the cemetery takes care of gravedigging for you, she says, “Here, you got to dig your own hole. If you don’t own a Hop Toe, then start digging last week!” The seed companies, with their earth-moving equipment, are often asked to step in, says Manera. “That’s a big burden lifted off the family. Usually on Molokai, when somebody makes – they die – one of the first concerns is, who will dig the hole?”

Some, like Kaunakakai bookstore owner Teri Waros, who worked for an environmental monitoring nonprofit before moving to Molokai 11 years ago, question the companies’ ulterior motives: “They go into economically depressed communities, and they’re the great big brother. They donate computers to the school, they give to this, they give to that. It’s easy to control people with job security in an environment where there’s no job security.” Waros brings up intention, something I heard time and again on Molokai, as a guiding principle: “What Molokai has taught me is that we have to be very conscious and honest about what our intention is. Because our intention sets the direction of the canoe.” Of the seed companies, she said, “I do not drink their Kool-Aid. I do not believe Monsanto’s intention is to feed the world.”

Maybe so. But what do you do in an environment where motives are almost never purely one thing or the other, where distant corporate intentions are opaque to the point of invisibility, and the reasons shareholders invest may not be the same reasons individual employees drive themselves to work in the morning? You look at what’s in front of you. And you make a choice.

David Makaiwi has made his choice. The Monsanto employee has 10 mouths to feed at home, including an adopted son and two foster children. On Facebook, as “GMOWarrior,” he defends the company he works for against vocal opponents who he says don’t understand what he does every day or the island he lives on.

“In a way, it’s not about the money,” he says. “It’s working for one good company who will back you all the way.”

I asked Ray Foster, who oversaw the last days of pineapple at Del Monte and returned to Molokai to be Monsanto’s site manager, about his intentions, and he chose his words carefully: “I would like for us to be perceived as a valued neighbor and associate, instead of a necessary evil.” But Foster has made his choice, too, and it’s for Molokai: “I’ve always felt like this was home. My children were born here. And whenever I thought of home, I thought of Molokai.”

The Molokai residents I spoke to were not necessarily against evaluation, regulation, transparency or accountability. But most of them thought the moratorium went too far. Kanoho Helm, a homestead farmer and musician whose father, Adolph, is the farm manager at Mycogen, put it like this: “You can get one hammer or you can get one wrecking ball. They both can do the same job, they can tear down something. But a hammer can also rebuild, it can restructure, it can look at regulation if needed, it can change. Everybody can carry on with their lives. But this is one wrecking ball. If (the moratorium) passes through and the companies pull out, it’ll be devastating for this island.”