Embrace Conflict

People in Hawaii often try to avoid conflict, but four local leaders explain how well-managed conflict is essential to an organization and its employees. They provide a nine-part road map for navigating conflict at your workplace.

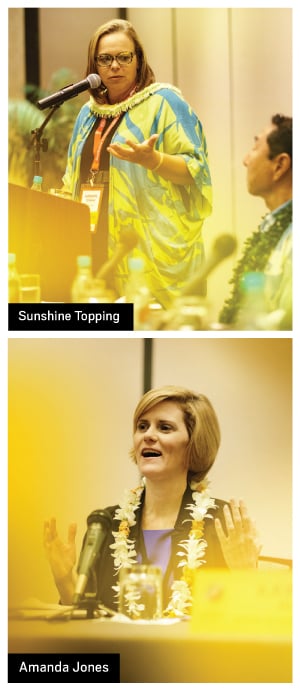

DISCUSSION PARTICIPANTS

This is an edited transcript of a dynamic workshop conversation held at the 2016 Hawaii Business Leadership Conference. The participants were:

Russell Hata, president and CEO of Y. Hata & Co.

Amanda Jones, partner at the law firm of Cades Schutte

Kawika Riley, chief advocate for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs

Moderator: Sunshine Topping, VP of Human Resources at Hawaiian Telcom

1. AVOIDING CONFLICT IS A BIG LOCAL PROBLEM

Avoiding conflict now can lead to lots of problems down the road, including a lawsuit your company will lose. Here are steps to take.

Photos by Aaron K. Yoshino.

Jones: If I was to pick out the problem I see most often, it is that managers and supervisors want to avoid conflict. As a result, they’re not dealing with performance issues with employees or not dealing with behavioral or misconduct issues because, “If I say something to them, they’re going to get upset.” Or, “I don’t know what their reaction is going to be. They might cry, they might yell, they might quit.”

Not doing anything about performance or behavioral issues allows them to continue and creates problems for the organization. If somebody isn’t pulling their weight, isn’t getting the job done, other employees have to pick up the slack and they will eventually resent it. Or the supervisor has to work harder to do the employee’s job and can’t focus on higher-level tasks, strategic thinking and other things the supervisor should focus on. The desire to avoid conflict ends up creating a lot more problems than if you had just tackled it head on.

From a legal perspective, if these issues are not dealt with, you end up in litigation because, let’s say, the employee is terminated and files a lawsuit. The employer needs to articulate the nondiscriminatory reason the person was terminated. If the reason is they were a poor performing employee, then the first thing a lawyer will say is: “Let me see their performance evaluations.” And how many times have I gone through this process and I see the performance evaluations are absolutely glowing? There is not a single issue or problem identified. Your own documents are going to hurt you, not help you.

Organizations need to provide managers and supervisors with the training to deal with employee issues. We shouldn’t just expect that people will understand how to deal with employees without giving them the tools with which to do it.

There are other tools available to employers to protect them against litigation, like having a well-written, up-to-date employee handbook that identifies the rules and discipline policies of the organization. Also, having job descriptions that are accurate, updated and that identify the essential functions and responsibilities of the position. That you have a policy for dealing with complaints about harassment and workplace violence. You have a procedure to investigate those complaints in a timely fashion and take corrective action. When there are violations, you document those things.

When you do performance appraisals, honestly reflect the issues employees have, counsel people over misconduct and document those things well. If you end up in litigation, but have documents that back up decisions you made, that gives the employer a lot of leverage. Some employment attorneys that represent plaintiffs aren’t going to take the case if they know there is this kind of documentation.

Hata: I agree with Amanda: The key is documentation. Confront the individual with the problem. Take out emotions, opinions and all that, and just stick to the issues and facts. The employees have got to be made well aware there is a problem with their performance and you’ve got to document it.

Topping: One thing that’s incredibly important for leaders is to have conversations with employees, document their performance. So many leaders will let poor performers continue, because they’re avoiding conflict or trying to be nice to that person. I always tell them: When you’re being nice to that one person, you’re actively being mean to everyone else. If there’s one underperformer on a team of 10, and you’re not doing anything about that, you’re being actively not nice to the other nine employees who have to pick up the slack.

Hata: You tell the employee: “I want to be nice, I like you, so I have to make you aware of the problem because I don’t want you to lose your job.” Spin it a little bit to make them feel as though you’re helping them, which actually you are.

2. DIFFERENCE BETWEEN GOOD AND BAD CONFLICT

Hata: I think any conflict is good because it makes you think deeper, it brings on more options and opportunities. It becomes bad when your opinions come from a negative side. So long as the purpose is always to help the other person or help the situation or improve the company, you’ll be OK.

Jones: Violent conflict is definitely not good conflict – not only physical violence but, in a broad term, aggressive, intimidating, abusive, threatening. That conduct should not be tolerated in an organization. I think healthy conflict in an organization is disagreements among people who remember they have a common goal and that conflict hopefully will flesh out the different viewpoints on an issue while focusing on that common goal and using the conflict to figure out new ways to do things, to figure out a more efficient and effective way to do things while also providing an opportunity for different viewpoints to be heard. So when ultimately you decide how to move forward, you have taken into account different viewpoints.

Riley: A lot of it comes down to process. When you engage in conflict, are you doing it carelessly? Just going where you feel like going? Or are you approaching that conflict with a sense of kuleana, a sense of responsibility, for how you behave and for the other person? How you engage in conflict is very important. Conflict can be good and bad based on what it produces, but often it’s bad process that leads to bad outcomes.

Topping: You almost have to have rules of engagement around how to approach conflict. That makes it easier. A bargaining-unit agreement is rules of engagement for how you deal with conflict. Anyone who works with labor relations, labor unions, would know that, too.

3. HOW TO ENCOURAGE GOOD CONFLICT

Topping: Since we do have a risk-averse culture in Hawaii, how do you encourage your team to know it’s OK to have conflict? And how do you bring that out in them without starting fist fights?

Riley: I think it’s important to stress that, nine times out of 10, more conflict leads to less conflict. And no conflict at all leads to blow ups. In a lot of ways, we do have a conflict-averse culture. We need to acknowledge that. But when we don’t deal with issues when they start, when they’re small, they don’t disappear. They feed off of silence and inaction, and they get bigger and bigger. Eventually those problems erupt.

For the most part, having that conflict, doing it more often, making it part of your practice, but doing it with care, I believe leads to less conflict and less explosive conflict in the long run.

Jones: For significant issues at my firm, we have committees comprised of both partners and associates. We try to make sure there’s diversity in the group. Not just racial diversity; we want to have younger associates as well as more senior; we want to have senior and junior partners, so as people retire, we have somebody with institutional knowledge about what the committee is doing who can take over. We also want people from different practice areas: some are litigators and others are transactional folks, and they approach the practice of law very differently.

We try to explain to new people on the committees: “You were picked for this position because you represent a particular viewpoint or group that we want to make sure is represented at the table.” Their input is important. They’re not only representing themselves, but a larger group of people, so it is important they come forward and disagree or criticize or make suggestions about how we can do things better. For the associates, we make it clear this is also your firm, it’s not just the partners’ firm. If you think something needs to be done, speak up. Don’t just sit back and complain, take ownership over the issue and over the firm.

I think it’s also important for the head of the committee to make sure those people feel comfortable that they or their criticisms are not going to be criticized, even if it’s a suggestion that ultimately isn’t implemented. I think when you make changes, particularly when it’s a result of input from a committee, that you communicate that we made this change because of input we got. So people know it is important they bring issues forward. Because if people complain about things, and nothing is ever done about them, eventually they’re just going to stop complaining. They’re going to give up.

4. THE VALUE OF ONE ON ONE

Russel Hata of Y. Hata & Co. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino.

Hata: My favorite core value at Y. Hata is candid communication. That’s because there are so many good ideas, but some people do not speak up in groups. So let them know they should speak up, encourage them to speak up in meetings, but also meet with them one on one. One on one, they’ll tell you all the truth. In a group, all the same people will speak, and others will never speak unless you force them. And when you force them, they get mad at you.

5. RECOVERING FROM BAD CONFLICTS

Topping: We all know how small this town is and you can burn bridges. If a conflict with someone doesn’t go well, how do you recover professionally in this town?

Jones: It depends on what happened. I’ve heard about judges in this town keeping a black book; if an attorney has done something really inappropriate, they will write their name in that book. I feel like a lot of people have their own mental black books so that if you do something, “I’m going to never forget it, and I’m going to tell everybody I know about it.” If you have done something that involves dishonesty or your integrity, quite frankly, I don’t know how you fix that. Because that’s going to be burned in people’s memory. And we are in a small business environment within the legal field, where you’re going to run into people again and again. So that can be harmful to your reputation for a really long time. To be honest, I don’t know how you get over that.

I think there are other kinds of things that you can get over. If you’re rude to somebody, if you screw up and don’t follow through with something that you said you were going to do, I think those things are recoverable. The first thing to do, of course, is to apologize. And it’s got to be a sincere apology, because people are going to smell a BS apology from a mile away. It can’t be one of those like I’m going to blame you while I’m apologizing. Like, “I’m sorry you didn’t take it the way I meant it.” [Laughter]

Also, try to find opportunities to work with the person again, indirectly or directly, so you can demonstrate that you aren’t a jerk or that you do follow through and you’re not a flake. Your actions are going to speak louder than your words, but coupled with the apology, I do think you can overcome many mistakes.

Riley: In instances when you have enough self-awareness to know you’re wrong and you’re willing to admit that to yourself, what’s the point of hiding that? Never underestimate the power of an authentic, articulate apology, and have the courage to do that when you know you owe it to someone. But underscoring Amanda’s point, don’t go there in the first place, if you can. Because it’s a small community, and there are times when that powerful, authentic apology isn’t powerful enough.

6. CAN CONFLICT LEAD TO INNOVATION?

Kawika Riley, chief advocate for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino.

Riley: Conflict is built into the public policy and legislative process, based on a belief that conflict will make outcomes better. Look at how bills start at the Legislature, how good those ideas are at the beginning. Then check in 60 working days later, after people have given input, different affected communities have weighed in from their perspectives, experts provide their manao. Whether it’s perfect at the end isn’t the question. The question is whether or not it’s better. The legislative process is based on the assumption that conflict makes it better. Otherwise, the Legislature should just accept every idea that every one of its members proposes on day one.

Jones: Lawsuits are one of the biggest conflicts organizations face. Often, after a lawsuit is resolved, the initial reaction is to say, “I am so glad that’s over. I don’t ever want to think about that again.” Successful organizations will see a lawsuit or other types of conflict as an opportunity to look at internal issues. Even if you did not do anything wrong, and you aren’t liable, there are always things that can be learned. A good person to point out improvements is the lawyer you hired, who through the course of the litigation, saw those issues in the organization.

But it doesn’t need to be a lawsuit. I think successful leaders see problems as opportunities. If you have a customer complaint, likely there are other customers who experienced a similar thing, they just didn’t tell you. Use a customer complaint as an opportunity to say, “Here’s a gap in our process.” Conflict often helps you to crystalize issues you need to address. Hopefully that can propel you into developing more efficient and effective systems.

One client was having small conflicts regularly. Ultimately those led to a bigger conflict on the same issue. It blew up, and there was costly and time-consuming litigation. That catalyzed the company to finally do something about the problem. What was needed was to get the law changed. The litigation, and all the time and money spent on it, was the push needed to do something about the law.

Hata: Conflict forces you to think deeper. It forces you to look at different perspectives, and you see more. Ultimately it will lead to a better decision or innovative ideas.

7. UNDERSTANDING THE OTHER PERSON

Jones: When you are dealing with anybody, you should think about that person’s communication style. Your CEO-types are very busy and have to make a lot of decisions. And because they’re so busy, they have to make decisions with limited information. So when you talk with a CEO-type who doesn’t have a lot of time, you better be able to succinctly identify the issue and identify options. Because if you offer too much detail, the CEO-type will feel like, “You’re taking up my time and you’re not getting to the point.” So figure out in advance what that person needs and tailor your approach.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, you have more touchy-feely, people-oriented people. You can’t storm into their office, say, “We need to deal with it,” and say what you want to do. Instead, start with, “How are you doing?” Chitchat a bit to make that human connection, then delve into the issue. Those people-oriented folks will want to know the impact of your solutions on individuals. You need to demonstrate you’ve thought that through if you want to have an effective response from that person.

Another personality type, the financial folks, the math and science types, they will want data. If you’re proposing a change, say to buy software that deals with a problem or addresses something new, they’re going to want to know, “What kind of a problem are we having? How many complaints did we receive? How many clients did we lose? How many potential clients could we gain?” You’ve got to have data to back it up or they won’t buy it.

Someone else may be bored by charts and graphs. They may want to hear a story or creative ideas. So you’ve got to tailor your approach. Figure out what the person needs.

Riley: It’s also important to remember that you’re communicating with a person. Not a job title, not your second appointment and not a sale. The more you understand where that person is coming from, the more successful you can be at whatever your responsibilities are. When you’re talking about your team, you need to know where they are emotionally. If you want to motivate people, if you need to defuse something bad, you need to go where people are emotionally. It’s not just about IQ, it’s also about EQ.

8. NATIVE HAWAIIANS

Topping: What are some major challenges in fighting for the rights of Native Hawaiians?

Riley: There are a lot of things, and we’re all familiar with them: Scarce resources, global pressures, cultural distances that feel like they’re getting further apart, not closer together. But the thing that concerns me the most, as a young person who cares about our Hawaii and feels passionately about Hawaiian culture, is there are certain role models telling bright, promising young people, young Native Hawaiians largely, that if you have a successful career as a public servant, maybe even if you have a successful career in the private sector, that makes you less Hawaiian. That makes you inconsistent with our people’s values and with the direction we need to go. I think that’s so dangerous. I think it’s so inconsistent with the way I was raised and with where our culture really comes from. If a non-Native Hawaiian said something like that, we wouldn’t tolerate it. But we do it to ourselves. So if there’s a challenge above anything else, to answer your question, Sunshine, I think it’s forces where we disenfranchise ourselves as a community. And that’s not good for anybody. Not good for us and not good for our state.

9. CONFLICT WITHIN THE GOVERNMENT

Topping: Kawika, how is conflict handled in government or quasi-governmental agencies?

Riley: Russell said earlier that, inside a family business, you have issues with ego, power, personal agendas. Luckily, you don’t see that in politics. [Laughter] Conflict is different across government: Each office, each agency, branch of government, and level of government has its own culture. What kind of conflict is considered appropriate varies based on those office cultures. Some people can work their entire lives in government – civil service track, protected positions – and have very little conflict. For others, conflict is inherent in what they do.

There are at least two constants in the public policy and legislative process. One is conflict, the other is compromise. If you’re not comfortable being in an environment where you need to be in a constant state of conflict and a constant state of compromise, juggling a variety of different issues, then you have no place in the policy process.

Ready to join us for our 4th Annual Leadership Conference? Learn more and register here:

hawaiibusiness.com/leadership-conference-2017-information/