Don Horner: First Hawaiian Bank CEO, Board of Education Chairman, Single Father

Donald Horner has a saying:”When life hands you challenges, you have two choices – you can be bitter, or you can be better.”

He’s chosen to be better.

The CEO of First Hawaiian Bank is both exactly and not at all like what you’d expect. He’s intelligent, conscientious, loyal and personable – everything you’d want in a banker whose job is to protect your money. But this especially private man also came from unexpectedly humble beginnings, didn’t aspire to greatness while young, lost his father at age 12 and is now a devoted single father raising two teenage boys.

While there is talk that the 60-year-old Horner is winding down a 33-year career at FHB, he’s made no formal retirement announcement. However, he is fully engaged as chairman of the state’s new, appointed Board of Education, which could become his greatest professional challenge. Horner was also selected by Mayor Peter Carlisle to serve as one of the 10 members of the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transit, which will guide the biggest construction project in the state’s history. He also sits on six nonprofit boards, teaches Bible study once a week, sent his oldest son off to college in Texas this summer and is building his retirement home on the North Shore. All that, and Horner insists that his life is stress free.

“I may cause stress, but I don’t feel stressed,” he says, with a chuckle. “I feel privileged to be able to work and serve and do my part, so I choose not to let small things stress me out.”

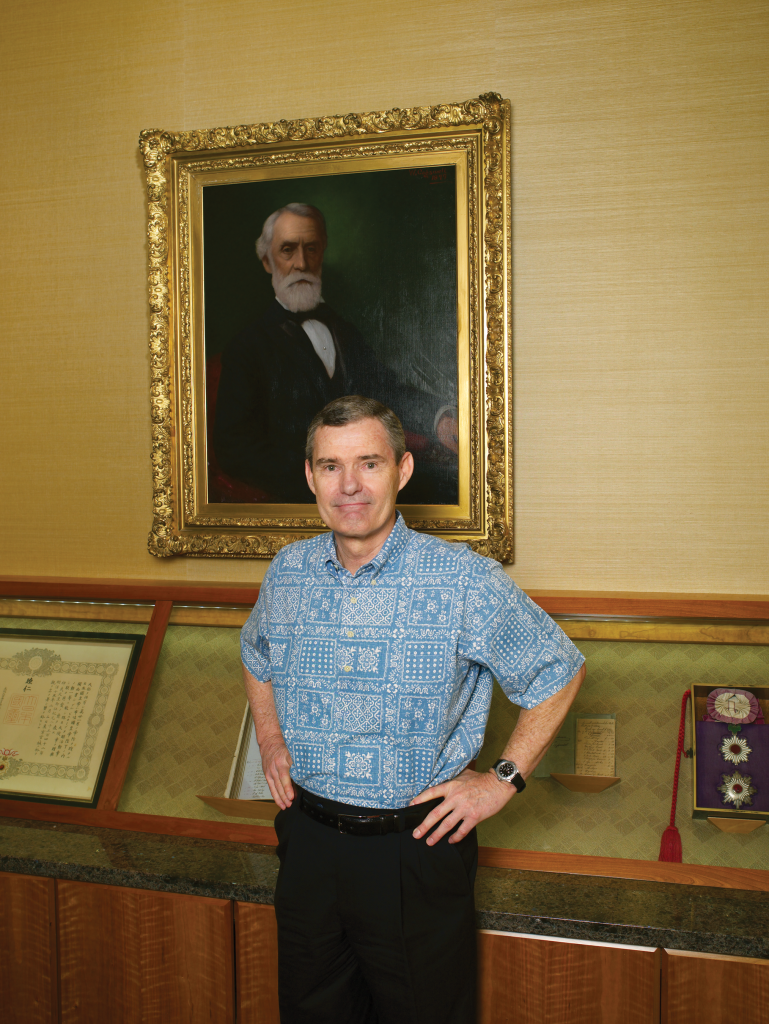

For my second interview with Horner, I visit his gorgeous office on the 29th floor of the First Hawaiian Center late on a Friday afternoon. He has been sick all week – something his assistants say is rare – and is still fighting a nasty cough and the sniffles. Emi Morikawa, who has been Horner’s assistant for 22 years, has spent the previous several days canceling his appointments, so I know he has a ton of work to do and the last thing he wants is to share his life with a reporter. But he is a good sport, patient and candid. As we chat, he multitasks and signs condolence cards for FHB employees who have recently lost loved ones, while soft piano music plays in the background.

“This little gesture means more to our employees than anything else,” Horner says of the cards. “This is why I’m not stressed – I have a great job and I work with great people. I feel very blessed to have the opportunities that I have and I don’t take any of that for granted.”

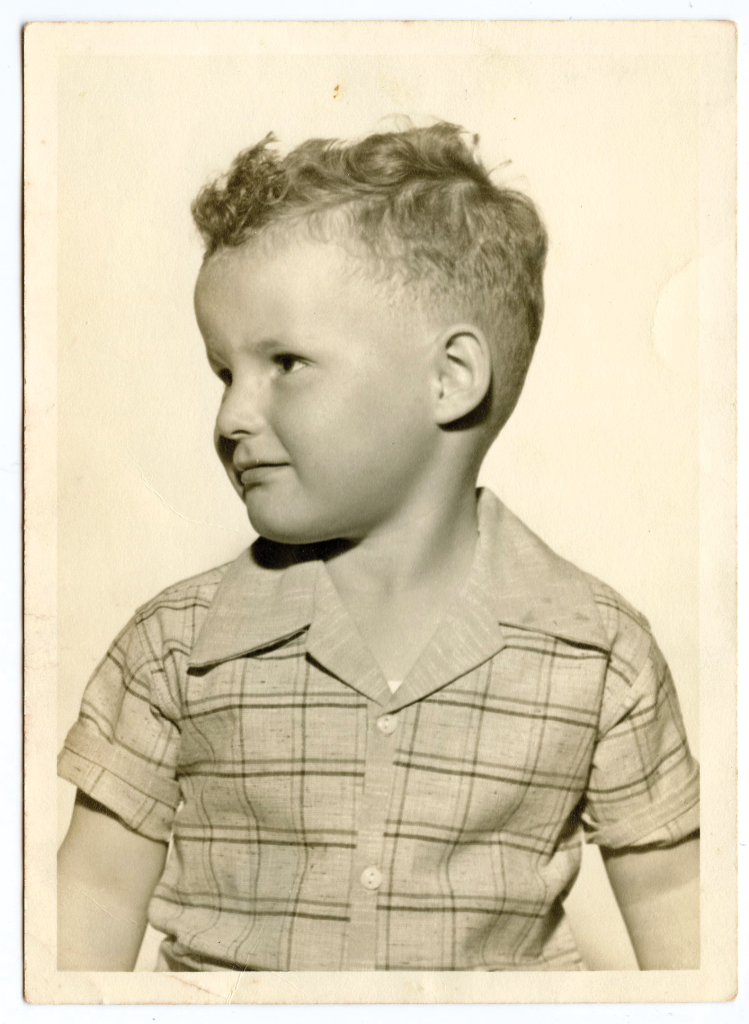

Horner’s had this same earnest, practical demeanor since he was a kid growing up in the small, rural town of Lumber Bridge in North Carolina.

“We didn’t even have a stop sign,” he recalls.

In fact, his senior class at Massey Hills High School only graduated 99 students, “The same 99 kids that I started the first grade with,” he says.

Horner says he learned problem solving and the value of hard work at his family’s general store, which was half the size of a typical ABC Store and far less shiny.

“One thing I learned by working at the store is that you treat every customer the same,” Horner says, a principle that’s guided his career. “I grew up appreciating the fact that everyone is special but that no one is more special than the next person.”

Horner is the youngest of three children and jokes that he was “the mistake.” His family was close because everyone worked together at the store, but his life was turned upside down when his father died suddenly from cirrhosis of the liver when Horner was just 12.

“He was an alcoholic and basically drank himself to death. When he came out of World War II (after serving in the Navy), he, like a lot of other people around him, became dependent on alcohol. He was hard working and a good guy. I loved him very much but, unfortunately, he made some bad decisions and died at 42 years of age.”

That taught Horner life isn’t always fair, “but it doesn’t mean you’re a victim,” he says. “That’s when I chose not to be bitter and instead did my best at becoming better.”

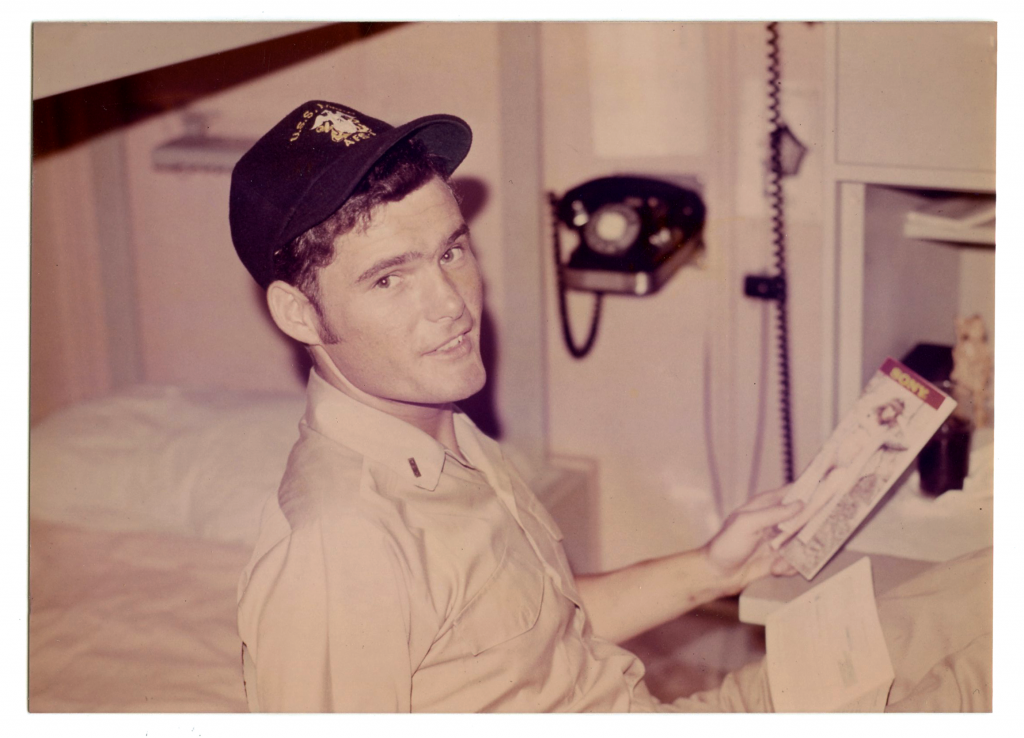

Horner signed up for the Navy at age 22, near the end of the Vietnam War. “Joining the military was one of the best decisions I ever made.

Horner, along with his older brother, knew he needed to step up and care for his mother, so he spent the next several years helping to run the store and mastering every job, from cleaning the floors to ordering inventory to watching the margins.

“I probably learned more about business in our small general store than I did in college. When something major like that happens to a kid, you have no other choice but to grow up, so that’s what I did.”

As a teenager, Horner enjoyed working on cars and began drag racing at 15. “I also had my first accident at 15. … The car flipped over and was wrecked, but you can’t hurt a teenager.”

Horner says he was a good student and graduated in the top 10 percent of his class. “But don’t forget, there were only 99 seniors total.” Of that group, some went to college and some went to jail. He was one of the lucky ones, he says, and planned to attend a small college in North Carolina.

“My whole aspiration was to be a forest ranger – a Smokey Bear, if you will,” he says, laughing. “I was the first in my family to go to college. When you’re from a small town where just about everyone is poor, college isn’t really something a lot of people thought about.”

Horner’s high school chemistry teacher recognized something special in him and suggested he apply to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the premier public university in that part of the South. He got accepted and eventually graduated with a business degree.

“The ’60s were a very interesting time. I went through the long hair and a little bit of the drugs, and then, at some point, I just sobered up, so to speak, and figured out I needed to get a life.”

So, Horner joined the ROTC, which, he says, wasn’t a popular decision during the Vietnam War, but it got him on the right track.

At age 22, Horner joined the Navy and learned to work under pressure. The war was winding down and, although he says he was never in any real danger, the tempo was that of wartime.

“We were a guided-missile frigate, so we basically tracked Russian jets. Our job was to protect our gun line, so we would fire missiles at the enemy aircraft.”

Horner says it was a privilege to be chosen by the captain to pilot the 400-person warship and he remembers the intensity of navigating through the Moroccan Straits in the dead of night.

“When I look back at that, I think about how remarkable it is because of the amount of risk the managers took in young officers, and that’s something we don’t do enough of today. In fact, I was having a conversation with some of our senior officers (at the bank) the other day about investing responsibility into our younger people more quickly. It’s so important.”

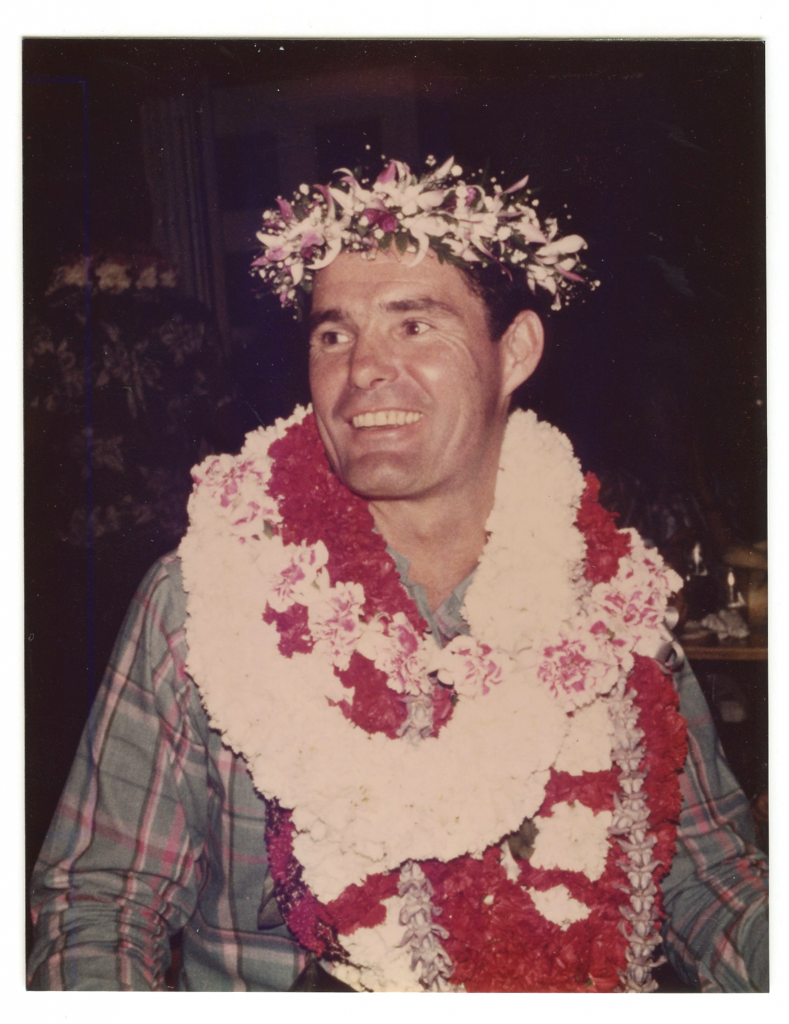

While enlisted, Horner lived in Kyushu, Japan, for a year and a half. He spent a lot of time cruising the island on his motorcycle and learned some of the language.

“Every time I would talk, people would laugh and I could never figure out why. It was bad enough I was a gaijin (foreigner) in Japan in the ’70s and I stuck out like a sore thumb, but then I also spoke like a woman because the person who taught me most of my Japanese was my girlfriend and I didn’t realize the language had both feminine and masculine nuances.”

On the day I visit Horner’s office, rather than shake my hand and spread the germs from his cold, he extends his closed fist and says, “Here, I better give you the knuckles,” which is the last thing I expect from the head of Hawaii’s largest bank. “Doozo,” he says, as he welcomes me into his office.

Later, when Horner shares that his pet peeve is inconsiderate people, I think back to the knuckles. As soon as I enter his office, which boasts breathtaking ocean and city views in three directions, Horner walks me straight to his mini-refrigerator and asks, “Nani o nomimasu ka?” (“What will you have to drink?”) in perfect Japanese.

I never would’ve guessed Don Horner was so Japanese.

Horner was 26 and a lieutenant commander when he got out of the military. “College was a blur and kind of a waste for me,” he says. “My college was really the military.”

With the help of the G.I. Bill, he got his master’s degree in finance from the University of Southern California. Afterward, he thought back to the times he had passed through Hawaii while on duty and realized it was the only place he could see himself raising a family and putting down roots.

“I strongly believe that, if you have confidence, you can be successful anywhere, and Hawaii is where I wanted to be.” It was in the Islands that Horner found the woman who “changed everything.”

After a short stint as an investment banker for Merrill Lynch in Honolulu, Horner joined FHB in 1978 as a credit analyst. “He came in as a junior guy and he was very smart,” saysWalter A. Dods Jr., who preceded Horner as chairman and CEO. “He could think outside of the box and could put together very complicated leases.”

Horner says he got into banking because it’s a stable, rewarding career. He talks about the satisfaction of knowing that many of the small businesses he helped in his early days are now large, thriving companies.

“There’s a difference in life between success and significance,” he says. “You don’t go into banking to get rich, just like a lot of other professions, like teaching or nursing, or even journalism, but the work can be significant.”

While on Kauai for business, Horner met Rowena.

“She was an oncology nurse and we literally had two beach mats together on the sand. She was studying and we just started talking.”

The two maintained a long-distance relationship for about three years. “I took a lot of last flights out of Lihue before I convinced her to marry me in 1990,” he says.

Meanwhile, Horner had been moving up at FHB and earned his stripes when he ran First Hawaiian Credit Corp. and First Hawaiian Leasing, two subsidiaries of the bank.

“He was hard working and success came because, in every job he had, he outperformed and set new standards,” Dods says. But, he wasn’t always such a straight arrow, he says, grinning.

“Everybody knows Don as a stern, forthright guy, but I fondly remember him as a rascal young bachelor, like we all were in our younger days,” Dods says. “He wasn’t quite as conservative as he is today. And then Rowena came along and, as every good woman can, she made a tremendous, positive impact on him. She was special.”

Rowena became an oncology nurse at Queen’s Medical Center and she and Horner shared a deep love. But, with the birth of their second child, Horner says, the doctors found lumps in her breast.

“She had breast cancer and it spread,” he says, taking a deep breath and pausing before continuing. “They gave her three years, but by the grace of God, she lived for eight.”

When I ask Horner about his biggest mistake, he thinks before answering. “Made a lot of those. But, if I had to pick just one, I would say not spending enough time with my wife. I wish I would’ve spent more quality time with her. Whenever you talk about someone you love who’s passed, you always say ‘would’ve, should’ve, could’ve.’ “

In some ways, Horner says, it was a blessing that they knew Rowena’s time was short because they made every day with their family count.

“We spent a lot of quality time together as a family, but it’s never enough.”

Horner proposed to Rowena in the fourth pew of their church, they married there, baptized their sons, now 18 and 15, there, and they buried her there when she passed away on April 19, 2004. About one month later, Horner was offered the CEO position at FHB.

He says he had no desire to run the bank and was content being president, which is more than he thought he would ever accomplish. Horner says his only goal at FHB was to have a deserved reputation of integrity and maintain a high level of trust and character. It was a tough time in his life, so he consulted his sons about whether he should accept the job. He could afford to retire and thought about just focusing on the boys, “but, surprisingly, both of them were strongly in favor of me not retiring,” Horner says. “I think they were concerned about me.”

Throughout his sons’ adolescence, Horner attended almost every soccer game and even coached their teams. Sen. Donna Mercado Kim, who sometimes exchanges parenting tips and stories with Horner because her son is about the same age as one of his, says Horner is a firm but fair father, and “it’s visible how much he loves them.”

“My life is balanced,” Horner says. “My job is not who I am. I was blessed with a beautiful wife and, in some ways, I was privileged. By losing her, it gave me more incentive to be a good father and invest in that job more than I would’ve if she was around. In some ways, being a single parent is almost a blessing. It’s a challenge, but you end up seeing both sides. When God gives you tragedy, there is blessing in that too. That experience made me a much better boss at work because I don’t take the job as seriously. It doesn’t mean I don’t work hard, because I do, but I don’t get stressed out about it.”

By this time, our conversation has turned from light to somber and I hope Horner won’t think my next question is insensitive. “How do you recover from losing your wife?” I ask, tears rolling down my face.

To my surprise, he’s not insulted and instead gives me an answer that I can tell he’s considered many times before.

“You can either get up and move on or just complain and wish it didn’t happen, and I don’t think God ever gives you more than you can handle,” he says.

“And what about your boys?” I ask. “How do you make sense of everything and explain it to them?”

“When you lose a parent, you have to grow up in some ways. It’s just a harsh life lesson and you have to deal with it emotionally and it’s something that’s going to shape your character, hopefully, in a positive way when all is said and done.”

In the middle of signing the condolence cards to his FHB employees, Horner reaches under his desk and pulls out an oversize, worn manila envelope filled with letters.

“You know what these are? They’re all the cards I got from the staff here at the bank when my wife died. I’ve got four more just like this and I’ve read every single one.”

He says he and the boys were blessed to have the support of their three families: “I will always be appreciative and indebted to the FHB family that helped us through that challenging time. Then, the Iolani School family (his sons’ school) was amazing, very nurturing, genuine and helpful. Then, there was our church family.”

Horner says he knows how his boys felt when their mom passed away because he lost his father at about the same age.

“My father wasn’t around long enough. I have the opportunity to make things different and better with my boys, and that’s exactly what I’m doing.”

Executive assistant Marcia Holbron, who helps Horner and other FHB executives, says Horner is a great dad – loving, affectionate, devoted – and never hangs up the phone when he’s talking to his sons without saying, “I love you.”

One way he’s trying to be a better father is by devoting his evenings to his family. A lot of CEOs accept that attending after-hours banquets and fundraisers is part of the job, but not Horner. He says he meets just as many interesting people and potential partners volunteering for nonprofit boards, which hold most of their meetings during the day. “My nonprofit work doesn’t take up as much time as people think,” Horner says. He currently is “fairly active” on three community boards and plays a lesser role on three other nonprofit boards. The BOE is his most time-consuming role, and he devotes one day a week to it, plus attends related meetings throughout the week.

Morikawa says Horner will occasionally attend night functions – “like if he’s being honored by an organization” – but Horner laughs and says, “I do my best never to be honored. I appreciate the invitation, but it’s just not who I am. I don’t want my friends to have to spend money to come see me.”

Horner isn’t comfortable in the spotlight. “He’d rather the bank get the credit for things instead of himself,” Holbron says.

Kitty Lagareta, chairman and CEO of Communications Pacific, who has advised business leaders on public relations matters for almost 25 years, says Horner’s done a good job of creating a strong brand for himself and the bank, even though he’s not as prominent in the media as some other CEOs.

“I don’t think you have to be in the media every day to develop a brand,” she says. “In our small town and culture, the people who gain the most respect aren’t the ones who talk about what they’ve done; it’s the people who do it and let their actions speak for themselves. Don doesn’t feel the need for a lot of chest beating and I think people really admire that.”

Horner starts his day around 6 a.m. and, until his older son recently got his driver’s license, took his sons to school every morning. He typically arrives at the office before 8 a.m. and, before he even turns on his computer or sips his coffee, he reads the Bible.

“Devotional sets the tone for the day and keeps me balanced.”

Horner says he’s read the Bible cover to cover many times but still learns new things. Throughout our interview, he recites long and short passages relevant to the conversation.

When explaining that he has no stress, he says, “Paul wrote the book of Philippians. What he said was, ‘be anxious for nothing,’ or, in other words, don’t let anything bother you.”

Horner realizes I am not a religious person, probably from the confused look on my face as he talks about Paul. “Now don’t get Philippians mixed up with the Philippines,” he jokes, “because that’s not what I’m talking about.”

Horner is very funny, with a dry sense of humor. When he shows me his Bible, which he keeps under his desk, he opens it to show me that it was signed and given to him by his high school buddy (he calls everyone “buddy”) for his 17th birthday, on Sept. 29, 1967.

“Hey, that’s my birthday!” I exclaim.

“You’re kidding,” Horner replies.

“I’m serious,” I assure him, but I can tell he doesn’t believe me. “Do you want to see my license?”

“Sure,” he says, looking directly into my eyes as if he’s calling my bluff.

I whip out my driver’s license, concealing my weight with my thumb, of course, when he takes it out of my hand and says, “Will you look at that? You weren’t kidding.” But, before he gives it back, he scrunches his forehead and asks, “What is all that?” pointing to my three-part Chinese-Japanese middle name, which, on my license, is erroneously separated by a series of commas.

“Oh, that’s my middle name,” I tell him.

“What a mess,” he says.

I learned that Horner is as honest as they come. He’s also very particular about things, especially food. No mayo, no gravy, no chips and not even wheat bread – all of which he says is “nasty.” I press him to tell me at least one of his guilty pleasures so we can agree on something, but he can’t even name one thing. He gives me a disgusted look when I suggest chocolate cake and French fries, so I drop it. That explains why he’s so slender.

Horner admits he’s disciplined when it comes to eating healthy, which is why he prefers to cook dinner at home with his kids rather than eat out. He also says he likes baking healthier pies, like sweet potato, pumpkin or yam.

Kim says Horner is not a typical CEO who enjoys fancy meals or nights on the town. “For someone with the amount of resources available, he’s not one to be flashy or over the top. He’s actually pretty frugal.”

Ask him and he’ll agree that he’s frugal. “Especially when it comes to other people’s money,” he says.

That’s good news for taxpayers, since Horner will serve on two of the most important public boards in the state – the statewide BOE and the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transit. Longtime friend Mitch D’Olier, CEO of Kaneohe Ranch, says there’s no question that Horner is the best man for both jobs. D’Olier describes Horner as focused, energetic and detail oriented.

“He’s one of the hardest workers I know, cares deeply about the children of Hawaii and providing them with a quality education, and he’s probably one of the best finance guys in Hawaii,” he says.

Horner was still only 34 when he became president of First Hawaiian Credit Corp. in 1984. “He was hard working and success came,” says Walter Dods, “because, in every job he had, he outperformed and set new standards.”

For Gov. Neil Abercrombie, it was a “no-brainer” when it came to appointing Horner to lead the new BOE.

“Don’s commitment to education is superior,” he explains. “From when I began my campaign to run for governor and learned there was a possibility that there would be a governor-appointed BOE, I told myself that if I ever got the opportunity, I would approach Don.”

Abercrombie says the word “sterling” comes to mind when he thinks about Horner’s character. “Although we have different personalities and we don’t necessarily agree on everything, we share the same values and that’s important.”

Horner talks a lot about values, but it isn’t enough to just have them, he says, “You have to live them.” When I ask Horner what that means to him, his answer gives me chicken skin.

“Values are what you do in the dark when nobody is looking. And, if there’s one thing I’ve learned over the years, it’s that nobody will care what you know until they know you care.”

As BOE chair, Horner will work closely with the superintendent of schools, Kathryn Matayoshi, whom he has known for about five years. Matayoshi describes Horner’s leadership style as hands on and willing to challenge the status quo.

“He is chairing the BOE at a time of tremendous change, opportunity and challenge,” she says. “His focus on supporting public education and willingness to make hard decisions in tough times will have long-lasting effects on Hawaii and our students.”

Reform won’t be easy. It’s acceptable to hand out marching orders when you’re running a private business, but, when you run a government agency, you must cultivate different constituencies and follow protocol. Kim says she has full confidence in Horner and his ability to work with others.

“I think Don will have his hands full with the BOE and transit board, but I know how organized he is,” she says. “He likes to get to the bottom of the issue and not dwell on minor things and let them bog him down.”

D’Olier and Dods also attest to Horner’s preparedness. By the way they describe him, I get the feeling he’s fastidious, but they’re trying to explain it nicely.

“You better know what you’re talking about when you get into his office, because he’ll have read page 732 and found the mistake on the bottom of the page,” Dods says.

D’Olier admits that, if he’s going to a meeting and knows Horner will be there, “I make sure I prepare extra hard because I know he will be (well prepared). I have to move my game up a little bit when he’s around.”

Horner understands the many obstacles he will face in his three-year term as BOE chair, but, as usual, doesn’t seem stressed. “I am confident that we will make the necessary changes – because we have to.”

Horner says he’s still listening and learning, but is aware that some of the major challenges are with human resources.

“In general, the state is not necessarily a great employer. Our teachers haven’t had a raise in two years. It’s tragic. There’s a great deal of administrative burden on our teachers and principals. Our systems are 30 years old and there’s very little automation. We’re working really hard, but sometimes we’re not working smart. The financial systems we have are very antiquated. There’s very little data to make good decisions. We tend to debate too much. I personally think there could and should be more rigor in the schools. I think our kids are highly capable and our expectations aren’t as high as they should be. I believe people can accomplish a lot if they’re given support and encouragement. I think it’s true for the kids, teachers and schools. I think we’ve set our expectations too low, and you normally get what you expect.”

Horner will be the first to admit that he has high standards. He makes no secret of his belief that to make improvements in the public school system, personnel changes are necessary. Horner acknowledges he can be demanding, but I sense he’s also fair, consistent and willing to work hard, and is always focused on the big picture.

After nearly two hours in Horner’s office, prodding him about his life and dreams, I decide it is time to ask the big question. I purposely wait until Horner warms up to me because I know it will be a long shot.

“You know how I said we would need photos to run with this story?” I explain, with my best winning smile.

“Yes,” he responds, squinting as if he knows I have something up my sleeve.

“So, I was thinking. … Would it be OK if we came over to your house to …”

He cuts me off. “Not a chance.”

“Please, we just want to get some shots of you relaxing on the couch, maybe hanging out with your boys … “

“Absolutely not.”

Horner is a self proclaimed “bishop nut.” In a conference room next to his office, he’s created a mini-museum to honor Charles Reed Bishop, founder of Bishop and Co., which became First Hawaiian Bank.

Earlier, I tried to invite myself over for dinner when he told me he likes to cook, but that didn’t work either.

“What if we don’t even come in – just hang out in front of the house or on the lanai?” I plead.

“I don’t know what to tell you, but it ain’t happenin’, girl.”

I give it one last shot. “Can you at least bring in some old photos of little Donny Horner standing in front of your family’s store, or from when you had long hair, or lived in Japan? Pleeeease. It’ll be so fun!”

“That’s the problem,” he says, rubbing his temples.

This is the first time Horner actually looks stressed.

“I’ll think about it, OK? Can we leave it at that?” he says.

We do. After he gives me “knuckles” one more time, I say, “Domo arigato.”

He replies, “Don’t mention it, buddy.”