Creativity in Their Business

Roberta Oaks, Fashion Designer and Retailer

Oaks did not start out to be a fashion designer. She majored in photography and art history, and then worked in restaurants for 10 years. Not until her late 20s did it hit her: “How am I going to make a living?”

Oaks was discouraged with the clothing options available in Hawaii. She had always worn slips as dresses and decided to try her hand at embellishing a few slips with ribbons, trims and appliques, turning them into one-of-a-kind little dresses. She enjoyed the process so much that she made 30 slip dresses and took them to a GirlFest event at the ARTS at Marks Garage. To her surprise, she sold 20.

Although she had no fashion background and didn’t know how to draft a pattern or develop a line sheet or a cohesive collection, Oaks expanded her dress sales to trade shows in major marketplaces such as Las Vegas.

Oaks is the first to admit that her fashion career has been all about, “One little accident that happens here or a mishap there. It’s about discovery. (In 2006), I found a trade show that was a good fit for me, Pool in Las Vegas.” Pool is for up-and-coming designers who aren’t ready for the huge Magic Show next door. Although the half booth she rented at her first show cost $2,000, a stretch financially, she came home with about 10 accounts from across the mainland and $25,000 in orders. A fashion business was born.

A desire to create new styles of her own led Oaks to find a manufacturer in Honolulu who could make patterns, cut and sew her first collection. “I shipped my first orders and then got a call from a (sales) rep who had seen my work in Santa Cruz and wanted to work with me. She took my accounts from 10 to 150 in the first year,” Oaks said.

Manufacturing has been a major challenge all along the way. “I’ve been through five factories in the past eight years,” she explained. “There were a lot of challenges doing it locally,” but she was committed to being a hands-on designer and that meant doing it all here.

In 2009, Oaks, realized her life had become strictly business. “I needed a shift in my social circle and wasn’t sure how to become more fulfilled in my personal life. … I felt so disconnected locally. I didn’t sell to any stores here. I felt weird making my product here and not selling it here.”

She had always “felt a connection with Chinatown,” so she talked with friend Rich Richardson of the ARTS at Marks Garage. “I need to be around creative people and I wanted to get involved in Chinatown,” Oaks says.

She had never considered opening her own outlet before, but the store at 19 N. Pauahi St. is now her financial mainstay and wholesaling has taken a back seat. “The funnest thing about having a store is that you get to introduce people to really great products they can’t find anywhere else,” she says with a grin.

Based on customer demand, Oaks started a line of men’s aloha shirts, which has done well. It has a vintage vibe that appeals to the hipsters who shop in Chinatown. Her shelves are stocked with a personal and eclectic collection of things, including hiking books, backpacks from Maui, messenger bags, flasks and fedoras.

“The store is a reflection of who I am,” Oaks says. “I am the soul behind this sole operation.”

And that’s just the way she wants it.

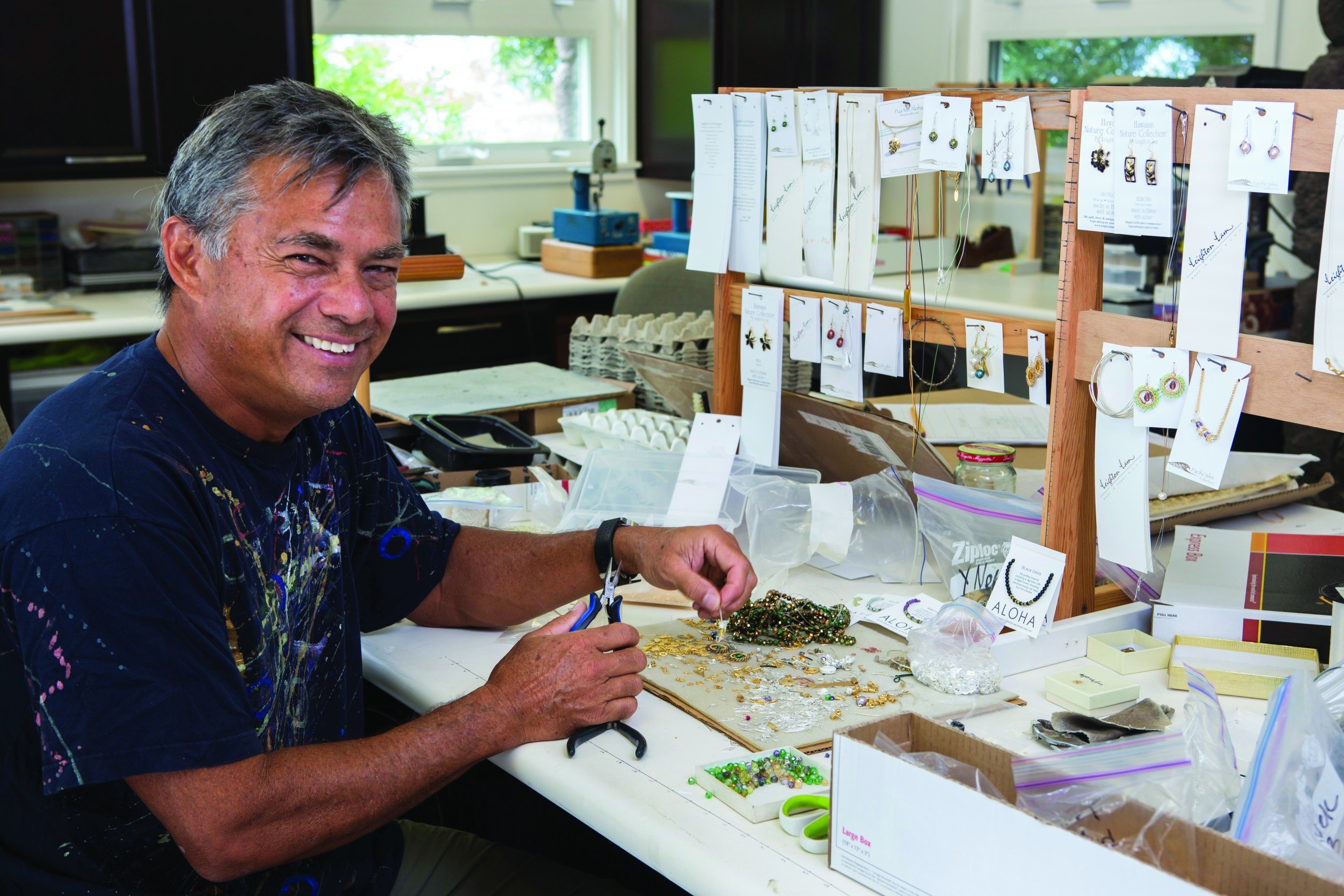

Leighton Lam, Artist and Jewelry Designer

At age 12, Lam discovered his two passions in life: surfing and creating art. He’s now 58 and, though there have been economic ups and downs, he has made a living as an artist virtually throughout his entire life.

Lam discovered surfing shortly after moving to Kailua in the fifth grade. His parents said: “If you want a new surfboard, you are going to have to learn how to make your own boards.” So he did.

Lam learned to shape glass and sand surfboards from some Pearl Harbor shipyard workers. He mixed resin with bright pigments and, after pouring it on the surfboard, tried some on pieces of plywood. It became his first resin painting.

After briefly working at a bank, a hotel and a restaurant, Lam decided to try to make a living as a resin artist. He rented a garage in Waimanalo and put together a one-man show in a Kailua bank. “I sold a lot of paintings and wanted this to be my life,” Lam says. He opened a gallery in Kailua that failed after 10 months, leaving him deep in debt.

Lam then rented a tiny studio on King Street and began painting full time, holding exhibits every few months, but, “It got pretty lean between art shows. It was a real struggle and lots of bounced checks.”

Lam sought an unusual, artful product he could build into a business. It was serendipity that caused him to take a second look at the tin cans filled with leftover, hardened layers of colored resin he used to create his paintings. “I knew there were over 100 layers of color in those cans,” he says. “I took my saw and cut the resin into small slabs.” He shaped and polished pieces and put earring backs on them and voila! “Ear Art” was born.

Photo: David Croxford

The brightly colored “Ear Art” rapidly gained a following that outgrew Hawaii. He hired a mainland sales representative and soon had hundreds of wholesale customers all across the country.

Lam married his wife, Lani, in 1978. She had a background in marketing as well as experience as an assistant buyer for Liberty House. “She is the business side of the business. She was a huge part of this process” and its success, Lam says.

The resin jewelry business exploded and Lam even had an order from the Federated buying group for 40,000 units of vibrant wearable art. Manufacturing at this volume was problematic in Hawaii. They tried having the jewelry made in China but it was a disaster so they brought the manufacturing back home to Hawaii.

In the late ’80s, the Lams stepped back to analyze where they wanted the business to go. “We realized that, in making jewelry for the mass market, we were ignoring the business in our own backyard,” Lam says. Island folks are more conservative and prefer subtle gold and silver to brightly colored jewelry. “How can we produce beautiful designs in metal with a classy Hawaiian design, but stay with the same pricing as the resin pieces?”

The answer: A closely guarded metal-cutting process used to create delicate Island-inspired designs. They began with the Hawaiian Quilt Collection, followed by the Hawaiian Nature Collection, which quickly found success in Liberty House and gallery boutique stores throughout Hawaii. They have since developed many new collections, including the Pacific Isle Collection and Liv-n-Aloha line. The newest is the Pacific Northwest Collection, which has been well received on the mainland. Their jewelry currently sells in about 250 stores, with 90 percent in Hawaii and 10 percent in Japan and on the mainland. They also developed Paradise Lights, a line of interior and exterior lamps, using the same metal-cutting process.

The change from resin to metal, as well as the economy, has meant a roller coaster ride for the business. In 1995, the company was making $400,000 to $500,000 in sales annually. It dipped for a few years, but in 2013 sales were over $900,000, Lam says. (Editor’s Note: The print version of this story has an incorrect sales figure.)

The stage is set for the next generation in this family business. Daughter Kaily Lam recently left her lucrative job at Google to join the family business as sales manager. This should further free her dad to simply make art.

Kawehi Haug, Cupcake Queen

When Haug and I were both working in the Island Life section of The Honolulu Advertiser, she often brought incredible baked goods to the newsroom. I particularly recall her amazing butter-cream frosting. She said she made it her mission to create the ultimate frosting.

After the Advertiser closed down in 2010, most of its journalists had to reinvent themselves, as Honolulu does not have an abundance of journalism jobs. I was not surprised when, in 2011, Haug opened a cupcake shop, Let Them Eat Cupcakes, at 35 S. Beretania St. in Chinatown.

Haug’s passion for cupcakes began when she was growing up in Germany. Every Christmas, her mother made cupcakes and, for 10 years, she worked at perfecting the frosting. While still writing for a living, she began making wedding cakes for friends. This segued into cupcake towers, because, “Wedding cakes are not as practical as cupcakes in Hawaii’s climate,” she explains.

“In the back of my head, I always told myself, at some point, if I’m forced to give up journalism, I might be brave enough to try baking for a living,” Haug says. Having a partner from the beginning, “Helped a lot so I didn’t have to jump alone. But it’s still scary. You don’t know if it’s going to work. My business plan was little overhead and low risk.”

Photo: David Croxford

Her business philosophy: “To do one thing and do it really well and to not water down your product.” So she decided to concentrate entirely on cupcakes. Although some customers asked her to start making coffee, she stuck strictly to cupcakes.

Having passed the three-year mark with her business, Haug recently opened a loose-leaf tea bar. The shop now offers nine varieties of loose-leaf organic tea made fresh with French presses.

Haug recently introduced Georgie Pie, named after her mother. It’s a pop-up concept, with pies offered the third Thursday and Friday of the month, from 11 a.m. until they sell out, which they always do. She also makes pies any time by special order.

Haug is happy with her location. “The food community (in Chinatown) is a supportive community. There is some small competition but mostly it’s, ‘You do what you do and I do what I do.’ ”

If Georgie Pie takes off, another shop may be in her future. She is also thinking about a custom-picnic-basket business. “My philosophy is to fill a niche that’s not being filled,” Haug says.

Let Them Eat Cupcakes supplies the Moana Surfrider Resort & Spa with 200 cupcakes a day for its afternoon tea, which has segued into providing all its specialty baking needs. It has been a lucrative contract for the little shop.

Let Them Eat Cupcakes has been a success from the get-go. It sells out every day by around 1 or 2 p.m. During the first year, it sold $20,000 per month on average and, by the end of the second year, it had increased 30 percent. May 2 marked its third anniversary.

Ira Ono, Artist

Ono is from New York, but he knew Hawaii was home the first time he set foot in Hana, Maui. He has lived on Maui and the Big Island for more than 30 years.

For Ono, who just turned 70 and lives in Volcano, an artist’s life has been the only option. Though there have been lean times and the whole “starving artist” syndrome is not new to him, he has always managed to make a living through art.

He majored in painting and ceramics at Temple University and in graduate school at the Brooklyn Museum School. He was on a sabbatical when he visited Hana and decided to stay. “I consider Hana my spiritual home,” he says.

Hana School had a kiln, so he taught ceramics to enable him to stay in Hana. After two years he moved to Makawao. He discovered Hui Noeau, a Maui nonprofit arts organization, had an old kiln. Ono restored the kiln, got a grant from the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and began teaching ceramics. He helped pay the rent with craft shows, mainly on Oahu, through the Pacific Handcrafters Guild.

Photo: Courtesy of Ira Ono

In addition, Ono opened Touchstone Gallery in Paia, which he later sold to the Maui Crafts Guild. While he loved Maui, “I knew I could not afford to live on Maui and would never be able to afford land there,” he said. “I heard Volcano Village had a lovely arts community. I came over for a weekend and discovered even a starving artist could afford to buy land, so I moved here in 1980. I lived in a tent for over a year until I built my little cabin and I’ve been here ever since.”

About 12 years ago, Ono bought the Hopper Estate in Volcano, built in 1908, and he has been restoring and growing the property ever since. He has renovated it into the Volcano Garden Arts Gallery, Café Ono, a vegetarian restaurant, and the Volcano Artists Cottage. The gallery features the work of more than 100 artists, including Ono’s own.

“It’s not easy, because I’m not doing commercial work. I was doing ceramic masks for many years. I never really did functional art, although I did some toothbrush holders,” he explains.

As a fine artist, Ono is constantly evolving innovative means of making a living. In addition to his ceramics, he created a line of wearable art called Ono Ribbon Scarves. They are sold at several locations on Oahu, including Riches Kahala, Silver Moon Emporium and Queen Emma Summer Palace.

There have been some rough times for Ono. “In 2009, the — hit the fan and it was a dangerous time to have a fine-art gallery that wasn’t commercial, but I was able to buy good art from good artists and somehow survived,” Ono says. Now he is thriving. Last year, he grossed $450,000 and currently employs six people.

It’s not surprising that Ono has taught a class called, “The Business of Art,” at Maui Community College for 18 years.

www.iraono.com

www.volcanogardenarts.com

www.onoribbonscarf.com

www.aweddingonthevolcano.com