CEO of the Year: Expanding the Queen’s Care

The Queen’s Health Systems was facing a difficult and expensive decision: whether to rescue the North Hawaii Community Hospital in Hawaii Island’s paniolo country. The hospital was considering bankruptcy, a path taken by other Hawaii hospitals in the past four years, and Queen’s had to be sure that rescuing one hospital would not endanger the many other health-care services it provided in Hawaii.

Art Ushijima, Queen’s CEO, felt he needed to gauge the community’s support for the hospital, so he flew to the Big Island three times to meet with leaders and ordinary people in the Waimea area to ask if they supported Queen’s plan for their hospital. Each time he found a receptive and grateful audience, says Kenneth Graham, the hospital’s acting president since January 2014.

“As a leader, he went out and met with the community personally, asking what they thought. He got universal support,” Graham says.

Those meetings meant a lot to Ushijima and to the North Hawaii community, where 30 percent of the residents are of Native Hawaiian ancestry. In January, Queen’s spent $800,000 to cover the hospital’s payroll and other expenses, and has committed millions more to renovate the hospital.

“We are a sole provider hospital for the people of North Hawaii,” Graham says. “We’re their emergency room, their birthing center, their medical surgical care center – without having to get on an airplane and fly off island or drive an hour and a half to Hilo.”

The Queen’s Medical Center – West Oahu, which opened in May 2014 after a complete renovation, is the only hospital serving the growing population of Leeward Oahu. Susan Murray, at right with Art Ushijima, was hired away from Kaiser Permanente to lead the hospital. Far right is North Hawaii Community Hospital in Waimea on Hawaii Island, which was considering bankruptcy before being rescued by Queen’s.

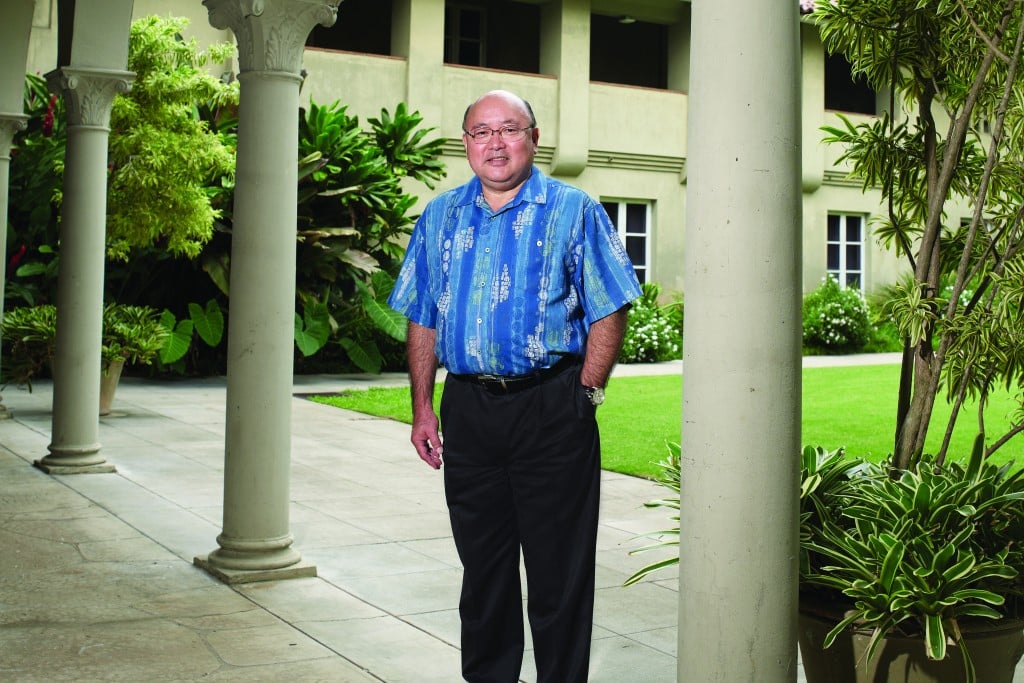

Over the past three years, Queen’s also renovated and reopened the only hospital serving the growing population of Leeward Oahu, and it saved the state’s only transplant center. Each time, it was Ushijima’s low-key but resolute leadership that made the difference in the rescue plans. Queen’s has been stretched mightily by the new challenges, but each addition to the Queen’s portfolio has strengthened the state’s health-care safety net. For those reasons and more, Hawaii Business magazine has named Ushijima as its CEO of the Year for 2014.

Ushijima is a man with a mission, and that mission is the one given to The Queen’s Health Systems at its founding in 1859 by Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV: Provide quality health care to the people of Hawaii – a mission that was given amid the devastating toll that Western diseases took on the Native Hawaiian population during the 19th century.

That historic mission is why Ushijima is not resting after all the expansion of the past three years: he and his team are forming a 10-year, $1 billion captial plan for redevelopment to expand Queen’s health care even further. “So long as sickness exists, the purpose of this hospital will continue,” says Ushijima.

Many people consider Ushijima the go-to guy for health care in all of Hawaii.

“When a health-care crisis arises, my first call is to Art, because I know he’s going to put his mission, which is care, ahead of any economic concerns, and that’s a big deal,” says state Sen. Joshua Green, chairman of the Senate Health Committee and a physician on Hawaii Island. “It wasn’t just bottom line for Art. He and Queen’s were concerned about the well-being of the people.

“Art has a long record of successes at Queen’s, but in the last three years he’s done three extraordinary things that have helped our system statewide,” continues Green. “I’ve known patients who survived because Queen’s stepped up with resources. Art made a series of very, very extraordinarily important and selfless decisions for his organization. Each will cost them money, but for the good of the state he made those decisions.”

Since 2012, The Queen’s Health Systems:

• Took over the bankrupt and closed hospital known as Hawaii Medical Center West in Ewa Beach, the only hospital serving the growing region of Leeward Oahu. Queen’s spent approximately $150 million to acquire, refurbish and expand the facility – including tripling its emergency room capacity – and reopened it in May 2014 as the Queen’s Medical Center – West Oahu.

• Reopened the Hawaii Transplant Center in January 2012, which had been closed for three months by the bankruptcy of the Hawaii Medical Center. Ushijima proudly says no transplants were moved to the mainland during that three-month transition.

“We knew if the transplant program closed it would be almost impossible to start a program from scratch,” he says. “We did a cash-flow analysis, and thought we could handle it, and then went to the board. We thought our losses would be between $5 million and $7 million, but we’ve been doing all right. The driving force was our mission.”

• Created its partnership with North Hawaii Community Hospital, with a capital infusion from Queen’s that kept critical services intact, covered payroll for the staff of 300, and kept the facility open.

Art Ushijima, right, with Bob Momsen, chairman of the board at North Hawaii Community Hospital, hold a news conference to announce the Hawaii Island hospital’s affiliation with Queen’s.

Under Ushijima’s tenure, Queen’s has also been active on the other side of the accounting ledger. The Queen Emma Land Co., the nonprofit funding arm of Queen’s, began the redevelopment of Waikiki’s rundown International Market Place this year. (Queen’s owns 18.5 acres in Waikiki.) Many locals and tourists miss the kitschy charm and the relatively cheap offerings of the Market Place amid the ubiquitous high-end shopping along Kalakaua Avenue. But it’s clear that Queen’s mission will be financially more secure when fed by the much-higher lease rents from the upscale shopping and dining center scheduled to open on the site in fall 2016.

The Queen Emma Land Co. also owns properties along several blocks of Kuhio Avenue. “Our focus has been on Waikiki and getting it redeveloped. We expect to see some more development along Kuhio,” Ushijima says.

The land company sold the Ohana Waikiki West hotel to BlackSand Capital last year and signed a long-term lease of the land at the same time. Ushijima confirms that remains the land company’s strategy: retaining ownership of the 10,500 acres bequeathed to the hospital by the queen, though not necessarily owning the buildings on those lands.

Patients in Waipahu, Kapolei, Waianae and other West Oahu communities were thankful when Queen’s reopened the region’s hospital in Ewa Beach in May 2014, says Susan Murray, senior VP for Queen’s West Oahu Region and COO of the hospital, now called Queen’s Medical Center West Oahu.

“What they say almost every day is, ‘We’re so grateful you’re here, and we’re grateful it’s Queen’s,’” says Murray. “They believe in Queen’s.”

However, the rapid expansion has not been without difficult issues, some of which made news. When the hospital, then named Hawaii Medical Center West, closed in December 2011, it displaced a lot of doctors and some were angry at Queen’s. Members of the Pacific Radiology Oncology LLC group sued Queen’s board and accused it of trying to establish a virtual monopoly on Oahu for radiation therapy by denying them privileges at the Punchbowl Street hospital. In early 2012, Judge Leslie Kobayashi issued a preliminary injunction ruling that Queen’s had to offer access to them, and the case remains in litigation.

Kymberly Pine, city councilwoman for District One, remembers her anger when Hawaii Medical Center West closed in 2012.

“I was very upset and I made it very well known,” Pine says. “The anxiety level was the worst I’ve ever seen in my community in my entire career. I’ve never had so many people call me crying. It devastated my community economically because so many people lost jobs, and there was so much anxiety for residents of the Leeward Coast in terms of feeling that they weren’t close enough to a hospital to have life-saving procedures.”

Queen’s and Ushijima were criticized for choosing to renovate the whole hospital after acquiring it, instead of immediately reopening the emergency room. “A lot of people wanted us to open the ER without the hospital,” Murray remembers.

During the renovation, Pine kept pressing Queen’s to move quickly. “I pressured them every month. I drove them crazy,” she admits.

When the hospital did open – fast-tracked by double construction shifts each day whenever possible – even the critical politicians came bearing a welcome proclamation, Murray says.

“They acknowledged that maybe health-care providers know how to do it right,” she says. “We really pushed to come online with quality results for the community as quickly as we could.”

Pine says Queen’s and Ushijima changed the quality of life in the area dramatically. “When Queen’s announced they believed in us, it changed everything for us. Not only did they open, they opened with a first-class facility that the people of the Leeward Coast deserved,” Pine says.

Green saw a huge ripple effect when Hawaii Medical Center West closed.

“That was a crisis for the entire state,” he remembers. “As patients were diverted from West to all the other facilities, those Oahu facilities that normally had no problem accepting patients from the Neighbor Islands had so much pressure on them that they couldn’t necessarily accept critically ill patients.

“By stepping up, Art created a positive effect statewide. I noticed immediately when West Oahu began to deliver services again. It immediately relieved the concern and pressure for me as a Neighbor Island physician. Our system is so intimately linked, we need leaders like Art to step up and take these responsibilities because it helps us all.”

But Ushijima is not resting on his laurels. Those who work closely with him say he’s a confirmed workaholic who “lives and breathes Queen’s and its mission.” He’s at his desk by 6:30 a.m. and stays there 12 or more hours, often leaving after 8 p.m. One thing he spends a lot of time on is thinking ahead. Over the next 10 years, he says, he expects The Queen’s Health Systems to pump $1 billion more into its network to upgrade and expand facilities.

“Our role is statewide,” he notes. “We have to assess what the future demand will be for services. There will be a lot more need for molecular genetics and geriatric needs. And I see more cancer and heart disease in the future.”

Chamber of Commerce Hawaii president Sherry Menor-McNamara, a new member of Queen’s board, remembers seeking Ushijima’s counsel when she first took over the chamber. “I was so impressed with the way he emphasizes teamwork and the way he leads his team,” she says. “The first thing he brought up is the ‘playbook.’ That’s their annual strategic plan and each year they update it. Each person (on Queen’s team) can monitor the progress.”

At board meetings, Menor-McNamara says, Queen’s management team reports the progress of each part of the plan. “Art uses the rules of the playbook and guides his team in fulfilling different goals, from patient care to the budget. They have different benchmarks and measure their performance based on those benchmarks.”

Menor-McNamara likes Ushijima’s “playbook” strategy so much she’s considering implementing something similar at the chamber.

Along with weighing medical needs and operating far-flung facilities (Queen’s also operates Molokai General Hospital), Ushijima works on the nuts and bolts of the recent expansion and what’s coming next.

“We’re looking at a long-term financing plan,” he says. “We’ll have to borrow a significant amount. A billion is a big number even for us,” he admits, noting that this projection has yet to come before Queen’s board, a group of unpaid volunteers that includes major business and community leaders.

Ushijima envisions an expansion of the 16.5-acre main Queen’s campus on Punchbowl Street. Within five years, he expects the old Cancer Center site and an adjacent apartment building now used for storage to be torn down and a new, 10-story tower dedicated to hospital rooms for patients erected there.

“Pauahi is getting pretty old,” he says of a Queen’s tower with patient rooms, built in 1971. “(Architectural firm) Group 70 says this is probably the best site to do another one.”

Robert Nobriga, Queen’s executive VP and CFO, says Queen’s plans to raise $200 million in new money and refinance another $300 million soon – as early as this year. “The financial plan assumes that all of our resources would go to supporting the reinvestment and that includes Queen Emma Land Co., which has the International Market Place as well as other Waikiki properties, plus property in Halawa,” said Nobriga.

“It has to be self-sustaining,” he continues, “and that’s a challenge in this current environment. With returns from our endowment and land company, and positive cash flow from our health-care operations, and collaboration and support from our payers like HMSA, we can get some of these large commitments turned around.”

Nobriga was lured to Queen’s this year by Ushijima, who first met Nobriga when he was a young financial wizard working for the UH Medical School more than a decade ago. He offered him a job then, but Nobriga was committed to go elsewhere.

“I remember telling Art, ‘If there is one health-care organization I would work for in this state, it would be Queen’s,’” remembers Nobriga. “It was because of the unique culture and vision they had – and Art lives the vision. Everything he says and the decisions he makes are in line with that vision and the mission of Queen’s.”

Nobriga came to Queen’s, at Ushijima’s request, to help create “a strategic financial plan and prepare the organization for a new era,” Nobriga says. “There was already planning that went into effect but we needed to take our planning to another level.”

Many community leaders and physicians praise Ushijima for accepting the risky challenges that Queen’s faced. Eric Yeaman, president and CEO of Hawaiian Telcom, as well as chair of the Queen’s board, calls Ushijima “an incredible and humble leader,” who has achieved far more in the past few years than any other CEO.

Walter Dods, former president and CEO of First Hawaiian Bank, says Ushijima knew that West Oahu needed support but also recognized that the existing hospital needed “to be torn down to the core and rebuilt to do it right for the long-term.” He also lauded Ushijima’s support of many other causes.

“You call him up on any campaign and Art steps up to the plate,” says Dods. “He writes a personal check first and then says what Queen’s is going to do.”

This picture, taken in 1898, shows the orginal Queen’s hospital, built on the same site where the medical center stands today. The building was made of coral blocks and California redwood, and housed 124 beds.

But no one is more grateful than Dr. Livingston Wong, the legendary 84-year-old transplant surgeon who inaugurated Hawaii’s first and only transplant center at St. Francis Medical Center in 1969.

Wong says Queen’s decision to save the transplant center was crucial for the entire state, but especially to the approximately 1,400 people who have undergone transplants in Hawaii over the last 45 years and the dozens more who get transplants each year.

“Art’s leadership is tremendous,” said Wong. “If there’s no center to do the transplant, then there’s also nobody capable of taking care of patients after the transplant. They need immunosuppression. They need the total care and they would have had to go somewhere else, maybe permanently. Patients continue to need followup forever. It’s a special thing to take care of immunosuppression. It’s not as though you can give it back to a family physician.”

Recently, Hawaii’s transplant program earned a Guinness World Record for the longest living patient who received a kidney transplant from a cadaver. That operation was done in 1971 and the young woman is still alive 43 years later.

Since Queen’s took over and re-established the Transplant Center in January 2012, there have been 140 kidney and liver transplants. The center is now considering adding pancreas transplants.

“The clinical results have been good,” Ushijima says.

Dr. Linda Wong, Livingston Wong’s daughter who is also a transplant surgeon, and the physician who heads the liver transplant program at the new center, points out that moving the transplant center to Queen’s required incredible courage by Ushijima.

“I applaud him for believing in us and taking that risk,” says the younger Wong. “Back when my dad was doing transplants, it was a leap of faith for the Sisters of St. Francis to take on transplants. But it only involved one or two patients who needed it. … (Today) there are more than 400 patients on the list and a staff of 20 people. Now there are a lot of financial implications and regulatory things, and it’s a huge job and a lot of work.”

She says Ushijima had to balance the possibility of saving the transplant center against the financial risks that could undermine the broader Queen’s mission. “In the scheme of things, Art is taking care of the rest of the state and he doesn’t want that compromised by taking a risk on 400 patients. But I think he felt an obligation to preserve this resource for the state. He’s saving a program not offered anywhere else,” she says.

Green, too, praises Ushijima’s role in saving the transplant center, as well as infusing new capital into North Hawaii Community Hospital, which offers thousands of residents an emergency room within half an hour of their homes.

“That hospital for years has been right on the verge of decreasing services or closing if it couldn’t survive,” says Green. “I’m forever grateful that Queen’s took that leadership role on my island. When I’m on call in Kohala, I know there’s a safe backup because of Queen’s commitment.”

Graham, North Hawaii Community Hospital’s acting president, says that when Queen’s stepped in at the end of last year, the hospital was running out of money and on the verge of filing for bankruptcy protection.

“It was a very big move by the Queen’s Health Systems under Art’s leadership to extend these important services to hospitals financially distressed and in high need,” says Graham, referring to both his hospital and West Oahu. “West Oahu had the second-highest ER volume in the state, right behind Queen’s on Punchbowl Street.” North Hawaii is no slouch, either: It handles 1,000 ER visits a month.

Graham and Ushijima have a weekly phone call so the boss knows how things are moving forward, while Murray drives in from West Oahu every week to personally update Ushijima on the West hospital that she says is so different from its former self that “it’s almost not comparable.”

“We’re more full service in terms of the amount of technology, and just the sheer number of services we offer,” Murray says. She predicts that many young physicians just starting their careers will open their practices in West Oahu, where there are a lot of potential patients and a more affordable cost of housing for themselves.

“We’re seeing tremendous growth there,” adds Ushijima. “With the opening, it has grown much faster than I thought.” The old Hawaii Medical Center West had 28,000 ER visits a year and Queen’s had projected 30,000 ER visits in the first year at its new hospital, Ushijima says. Instead, it’s already expecting 45,000 this first year.

“The demand has always been there and, with the population growing, we expect to see more. We’ll need to get more staff, and we’ll use flyers,” he says, using the term for nurses flown in from other areas. “There is a nursing shortage, and a skill-set shortage of specialty needs, including critical care, emergency room, surgery and behavioral health.”

To help with the shortage of doctors, Ushijima supports residency programs for students at UH’s John A. Burns School of Medicine. That allows medical school graduates to work in clinical settings for several years to gain experience.

When Ushijima looks ahead, he carefully measures each step that Queen’s takes. He looks at Queen’s overall future the way he looked at the West Oahu hospital. “We took the time to plan the facility and we took the time to do it right,” he says. “We knew we’d only have one chance to do it right.

“One of the reasons we take these things on, is to go back to the original vision of Native Hawaiian health. We’re always trying to strengthen that original vision.”

Maui Boy Comes Home after mainland career

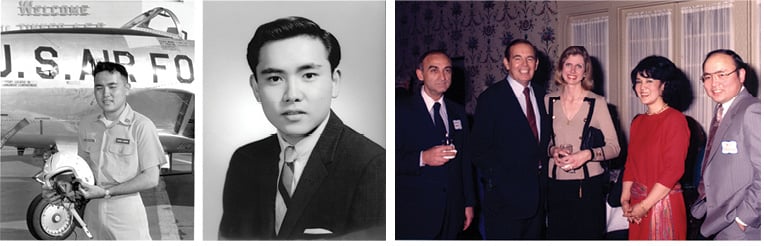

Art Ushijima as a ROTC cadet at Tinker Air Force Base in Oklahoma in 1970, as a 1966 graduate of Baldwin High School on Maui, and with his wife, Ruth, and Dr. Christiaan Barnard, the world’s first heart-transplant surgeon. Barnard is second from left, flanked by Dr. David Sokol, chief of cardiac surgery at Akron General Medical Center and his wife, Christine Sokol.

Art Ushijima was born in Wailuku, Maui in 1948 and graduated from Baldwin High School in 1966, but he spent the first half of his adulthood on the mainland.

He attended Cornell College in Mount Vernon, Iowa, where he received a B.A. in biology and courted his wife, Ruth, also from Maui. They were married after graduation and Ushijima went on to earn a master’s degree in hospital and health administration from the University of Iowa while Ruth taught school.

From 1973 to 1980, Ushijima served as an officer in the U.S. Air Force Medical Service, taking on administrative duties at two Air Force hospitals as well as serving as a staff officer for the Air Force surgeon general.

After leaving the Air Force, he held various positions with civilian hospitals, including executive VP at Akron General Medical Center in Akron, Ohio, and CEO at St. Mary’s Hospital in Kansas City.

In 1989, he came home to Hawaii to serve as executive VP and COO at Queen’s. In 1992, he was elevated to interim president and, a year later, named president of the Queen’s Medical Center, a title he still holds. In 2005, he was appointed president and CEO of The Queen’s Health Systems.

The Ushijimas have a son, Ryan, who is married and living in Florida, where he’s an IT specialist working on the computerization of medical records.