Cafeteria Culture

Google and other high-flying companies have reinvented the corporate cafeteria. The local cafeterias we visited are not that lavish, but they still cost plenty of money. It’s all worth it, the companies say, because their investments pay back in many ways, including improved collaboration, new customers and happy employees.

If it’s lunchtime, you’re probably reading this at your desk while eating.

That makes you among the 40 percent of people who lunch at their desk. It also means that you don’t work for Hawaiian Airlines.

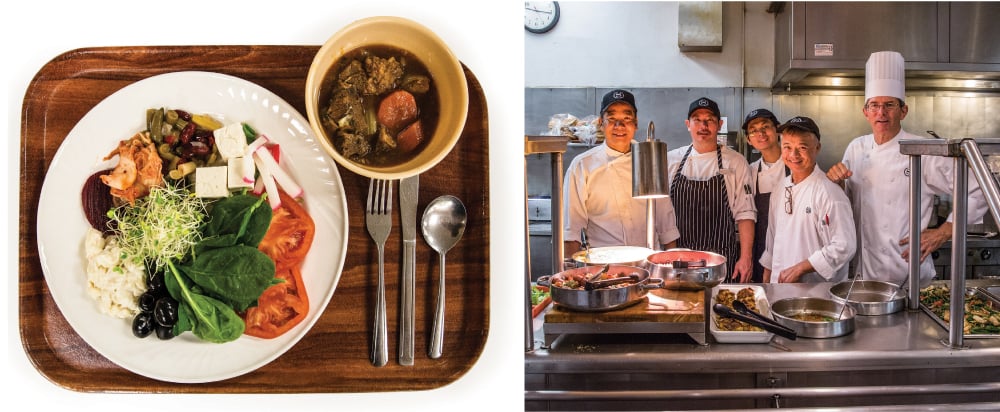

Hawaiian Airlines’ Lunchbox cafeteria at Honolulu International Airport. Photo: David Croxford.

At the end of 2013, when Hawaiian Airlines renovated its corporate office at Honolulu International Airport, knocking down walls for an open office layout, the company decided it wouldn’t allow employees to eat at their desks anymore. Instead, it pointed them to the bright, high-ceilinged communal dining room, where they could either bring their own food or buy it at LunchBox, the new corporate cafeteria.

At the Hawaiian airlines cafeteria, LunchBox’s mediterranean salad includes niihau lamb merguez, bell pePPers, ho farm cucumber, red onion, feta, kalamata olive, tomato, balsamic vinagrette and mao organic “sassy” greens.

Nationally, only 18 percent of companies have cafeterias, according to the Society of Human Resource Management. Though institutions such as hospitals and hotels have long provided food for their employees, it’s the bacon kimchi hot dogs and Northern Indian daal from Google, Facebook and other Silicon Valley companies that attract attention (and Yelp reviews) to corporate cafeterias.

Companies that choose to offer subsidized food to employees cite reasons such as boosting morale and saving time. In “Work Rules: Insights from Inside Google That Will Transform How You Live and Lead,” Laszlo Bock, the company’s senior VP of people operations, writes that Google designed restaurants and microkitchens throughout their campuses to encourage employees to leave their desks and connect with other people they may not normally encounter.

That was a driving force behind Hawaiian Airlines’ new dining space. “This is a really interdisciplinary business,” says Avi Mannis, senior VP of marketing. “We can’t get a plane up in the air without the collaboration of hundreds and hundreds of people … So you would think it would make sense for us all to get together and eat. But we never had a space to facilitate it. People would eat at their desks or in conference rooms.”

Owner Mark Noguchi with the LunchBox cooking crew. Photo: David Croxford.

When the company redesigned its headquarters, incorporating a dining room was “one of the first big decisions we made,” Mannis says. Now, a cross-section of departments and occupations eats in the dining room, from IT to airport baggage handlers to flight attendants in training. When CEO Mark Dunkerley is in town, he’s there, too, making it a habit to eat with different people. “He uses this as a platform to hear about developments, what they’re working on,” Mannis says.

“The space itself has had a really big impact on the way we work, the way we relate to each other. We see exactly what we had hoped for: People with different job functions having conversations.”

— Avi Mannis, Senior VP of Marketing, Hawaiian Airlines, on the company’s cafeteria

But the LunchBox burger and turkey reuben panini come at a price. “There’s clearly a cost to having it,” says Mannis. “It’s a space that has to be cleaned and maintained. It was a big capital investment to build out the kitchen.” From the vendor side, Mark Noguchi of Pili Group, who runs the cafeteria, says initial complaints centered on portion sizes (too small) and prices (too high). “Hawaiian Airlines wanted us to provide our style of food at a price that’s competitive to the fast food out there,” he says. Now, he manages to strike a balance: Everything, from the paiai burger to market vegetable Japanese curry, is under $10, and he’s able to uphold his standards of local sourcing because Hawaiian subsidizes his rent.

The hardest challenge? Getting everyone to step away from their desks at lunchtime. In addition to being busy, there’s the social awkwardness that dredges up memories of high school. Mannis says, “People were nervous about showing up and not having anyone to sit with. There’s a degree of anxiety.” Not that any of this is apparent come Sugar Rush Fridays, when fresh-baked cookies are offered in the afternoon, and employees line up for four cookies to four dozen. Food, especially warm chocolate-chip cookies, brings everyone together.

A cafeteria at the Hawaiian Airlines corporate office also makes sense given the limited food options at the airport, but what about downtown, where dozens of eateries cater to hungry workers and where the Bank of Hawaii has had an employee cafeteria for decades?

“Anytime you have your own dining facility at your place of work, it’s going to be a much more comfortable dining atmosphere,” says Wilson Chan, the bank’s GM of food and beverage. “It’s a benefit, a convenience.”

Bank of Hawaii’s Cafe Blue is open to the public, and offers open seating and a large selection of food. Photo: David Croxford.

He oversees Cafe Blue, the casual takeaway counter that is also open to the public, and the Surfrider, a formal, private dining room modeled on sit-down restaurants, where Bank of Hawaii employees can entertain clients. The Surfrider can also be set up for private events: “It’s a big advantage to have an entire space where you can have cocktail functions and custom menus,” Chan says. “As a company, it’s always good to have that in your pocket.”

Bank of Hawaii contracts ECHS, a local catering company, to carry out the logistics of running Cafe Blue and Surfrider. There are neither menu prices nor a check at the end of a meal at the Surfrider (bills are sent to the host’s department), and employees receive a 20 percent discount at Cafe Blue. It’s also one of the few corporate cafeterias open to the public, and it receives enthusiastic Yelp reviews for its food, which includes hamburgers, panini and fresh-catch specials, all of which are under $10. Cafe Blue caters to about 350 diners a day, and 20 percent of those are nonemployees. Why is it open to the public? Chan says it’s sort of a marketing tool, drawing in people (aka potential Bank of Hawaii customers). “It’s strategically placed, you have to walk through the branch,” he says.

Bank of Hawaii’s Cafe Blue. Photo: David Croxford.

In addition to offering daily specials to vary the menu, Cafe Blue holds monthly pop-ups run by Bank of Hawaii executives. At the last one, vice chairman and chief administrative officer Mark Rossi turned the cafeteria into a burger joint with six different burgers on the menu.

“It helps build camaraderie,” says Chan. “The executives are here to talk to people – it’s great engagement.”

For large hotels, an employee cafeteria isn’t an option, it’s a necessity. With hundreds of employees, 30-minute break allowances, and few affordable dining options nearby, a cafeteria makes sense.

At hotels such as the Halekulani and Sheraton Waikiki, meals are free. “It’s a hidden paycheck,” says the Halekulani’s in-room dining manager, Ed Hope. The cafeterias are such large operations they require a dedicated staff. The Halekulani’s cafeteria, which is open 24 hours a day, with the main meal service around lunchtime, employs two full-time cooks serving 400 people at its peak, more than a lunch service at Orchids. At Mokihana, the Sheraton’s employee cafeteria, two full-time cooks (three when the theme is Hawaiian and more prep is needed for the laulau and kalua pig) and two dishwashers serve about 800 employees a day from the Royal Hawaiian and Sheraton Waikiki, comparable to the number of diners served at Sheraton’s Kai Market.

Mokihana, the Sheraton Waikiki’s employee cafeteria. Photo: David Croxford.

“The cafeteria is as important as the restaurants,” says Daniel Delbrel, the director of culinary for Sheraton Waikiki. Mokihana’s numbers reflect this: It costs $2 million a year in food alone to supply the cafeteria, working out to about $5.81 spent per person per meal. Taking the standard restaurant rule of thumb, where food costs account for a quarter of the budget, that amounts to the equivalent of a $24 restaurant meal.

Mokihana at the Sheraton Waikiki’s salad bar. Photo: David Croxford.

Delbrel says it’s a directive from Kyo-Ya, the Sheraton’s management company, that they don’t skimp on Mokihana’s budget: “We see oxtail, we see prime rib, we see everything short of lobster,” he says.

The Halekulani also applies some of its restaurant standards to its employee cafeteria; for instance, it uses Plugra, a European-style butter that’s four times the cost of regular butter, and swaps out the cheaper Calrose rice for Tamaki Gold, a decision by the former executive chef, Vikram Garg, who said, according to Hope, “What’s good for the guest is good for the staff.”

Taco Tuesday and the monthly oxtail soup, made from a recipe handed down from an employee cafeteria cook 30 years ago, draw the most enthusiasm. Brian Oshiro, the cafeteria cook, keeps the menu varied – one week’s menu ranges from beef hekka to pork gisantes to shrimp po’ boys – which makes it especially difficult hard for the Halekulani’s purchasing department. Kobey Matsushige, the assistant purchasing manager, says buying for the cafeteria is more difficult than for any other aspect of the hotel. “It’s a higher volume than what we would bring in for the restaurants,” she says. “It’s a one-time bulk order to feed everybody. That’s a bit challenging for our vendors sometimes. They’ll say, ‘Three hundred pounds of meat, are you sure? One hundred pounds of yakisoba!?’”

The sheer volume of food preparation can be daunting. When Kervin Leval, Mokihana’s cook, makes oxtail soup, he starts with 600 pounds of oxtail and uses three 70-gallon steam kettles for 200 gallons of stew. Made-to-order hamburgers, hot dogs and saimin, plus a salad bar, cake, ice cream and a soft-serve machine are always available at Mokihana, in addition to the daily specials.

“The biggest challenge of running an employee cafeteria is that your customers are repeat customers. They come back again and again, and you have to keep it fresh and interesting.”

— Daniel Delbrel, Director of Culinary, Sheraton Waikiki

And they come back with complaints if they don’t like the food. “When you screw up a hamburger at a restaurant, you get one complaint,” he says. “You screw up a hamburger here, you get 600 complaints.”

(left) A custom-made salad plus beef stew. (right) Daniel Delbrel (far right), Director of Culinary for the Sheraton, and the Mokihana crew. Photography: David Croxford.

Still, in some ways, cooking for the employee cafeteria is one of the best gigs as a cook. Leval, who has worked in Sheraton’s other outlets, gets creative control of the menu (which recently featured his special soup, a Filipino chicken noodle soup with quail eggs) and serves his peers. “I love where I stay now,” he says.

“Cooking for the employees, especially the housekeeping, they’re the backbone. If they’re happy, I’m happy.”