Businesses Support Public Schools

The new track at Lahainaluna High School on Maui, along with the field and turf, have been made possible because of millions of dollars worth of in-kind and cash donations by Maui businesses and residents. Additional changes are coming in the future.

The new track at Lahainaluna High School on Maui, along with the field and turf, have been made possible because of millions of dollars worth of in-kind and cash donations by Maui businesses and residents. Additional changes are coming in the future.

Athletic facilities at Lahainaluna High School, Hawaii’s oldest public school, were so inadequate that track athletes had to leave the West Maui campus and train in Wailuku. And an inordinate number of students were getting injured.

The state was unable to pay for a new outdoor stadium and facility, so individuals and businesses stepped up. Part-time resident Sue Cooley started the ball rolling by pledging donations that have now totaled more than $4 million. Hawaiian Dredging prepared the site with more than $50,000 worth of work. Maui Westin Resort and Spa offered a $300,000 package of rooms to house the workers from Texas who installed the turf, although the full amount wasn’t needed. Dozens of others also chipped in.

“Without the support of local businesses, it wouldn’t be the same,” says Jeff Rogers, development coordinator for the Lahainaluna Foundation, which has raised more than $5 million for the school since the foundation’s birth in 2002.

Various versions of that generosity are taking place all over the state as businesses donate money, workers and volunteers to help public schools and their students.

It’s impossible to add up all the donations, but the results can be seen in painted schools, new playgrounds, renovated classrooms and science labs, landscaping, and donated books. Volunteers read to children and school supplies are given to youngsters who can’t afford them. And much of it is done without public money or even much public notice.

The state Department of Education tracks donations amounting to $500 or more – those have totalled $25.19 million statewide since 2000 – but that’s only the tip of the iceberg, says DOE official Judy Nagasako.

“Many companies have always given donations to schools to help them. But, increasingly, they’re coupling their philanthropy with company volunteers. They’re encouraging employees – even rewarding them – for taking an active role in volunteerism. That’s the trend,” says Nagasako, the department’s education specialist for corporate and community partnerships.

The DOE encourages schools that have strong alumni bases to create private foundations and Lahainaluna, McKinley, Roosevelt, and Farrington high school alumni have each set up foundations. Help also comes from alumni associations – often lead by graduates who have become business leaders in the community. Take Roosevelt High, for example.

The DOE encourages schools that have strong alumni bases to create private foundations and Lahainaluna, McKinley, Roosevelt, and Farrington high school alumni have each set up foundations. Help also comes from alumni associations – often lead by graduates who have become business leaders in the community. Take Roosevelt High, for example.

“Our robotics club is going off to an international competition, and the alumni association donated $5,000 to help with the robots and travel costs,” says Roosevelt principal Ann Mahi. “As well, Dwayne Nasu, president of Acme Fender & Paint Shop, a 1969 grad, made a personal donation of $5,000 to help. They’re all looking at the broader picture of supporting student achievement.”

A few months ago, Walmart gave $100,000 to the Public Schools of Hawaii Foundation. It was a big gift for the 25-year-old foundation, which expects to raise no more than $200,000 to $300,000 a year, mostly from a fundraising dinner at which Hawaii businesspeople buy tables.

Walmart’s donation allowed the foundation to allocate $250,000 to transform an existing classroom at Roosevelt into a modern science lab. It will be completed before the end of this school year. The foundation also plans to spend another $75,000 for professional development for science teachers.

The donation came because of a vote by the Walmart employees, says Nolan Kawano, executive director of the public schools foundation. “Walmart has a choice program and they informed us last year we were nominated. We went up against several nonprofits (for the funding) and the winner was chosen by a direct vote of their employees.”

Stephen Schatz, district superintendent for the Roosevelt complex of schools, welcomed the project. “If we want to prepare our students to be globally competitive, they need top-notch, state-of-the-art facilities.”

It will take an estimated $27 million to renovate and update all the science labs in the state’s 46 high schools, and the state is unlikely to finance all those improvements soon. That makes the business/school partnership crucial.

“We can’t do it alone,” says Schatz. “We need financial assistance to get work done. Working with businesses allows us to be a little more nimble with our resources.”

When the money comes from a foundation – not through official DOE channels – the work can proceed far more quickly, even though the department must still approve plans, he says.

“It just couldn’t happen this quickly if we were going through the typical repair cycle. There’s no way that, in nine months, you’d get a big project like this accomplished.”

The public schools foundation helps in other ways. For instance, it spends as much as $300,000 a year on an average of 70 “Good Idea Grants” for teacher projects, which range from $1,000 to $3,000 each.

Help for Hawaii’s public schools comes in many forms: It’s not unusual to find Hagadone Printing Co. employees reading to students at Puuhale Elementary in Kalihi. Or Deloitte accountants spending a Saturday cleaning a schoolyard. Or the electric company setting up summer internships for high school and college students.

Help for Hawaii’s public schools comes in many forms: It’s not unusual to find Hagadone Printing Co. employees reading to students at Puuhale Elementary in Kalihi. Or Deloitte accountants spending a Saturday cleaning a schoolyard. Or the electric company setting up summer internships for high school and college students.

“This makes sense to support our schools,” says Faye Chiogioji, manager of workforce services for Hawaiian Electric Co. “It’s good business, too – to develop the workforce with the skills we need.”

Employees from the Old Lahaina Luau collect and deliver truckloads of school supplies to Maui schools every year. “Last year, we did something different: We called the schools on the west side and asked what were the top five supplies they needed and we made up our own kits,” says Julie Yonayama, director of employee and community relations.

“We had 387 boxes of pencils, 387 reams of copy paper, 387 rolls of paper towels, 1,935 composition books and 1,935 portfolios. Mainly our goal is to donate to several schools. Those are our future employees.”

“You think of the long term,” says Ian Kitajima, spokesman for Oceanit, a high-technology company that coaches robotics teams and mentors students in science projects. The Public School Foundation recently honored the company.

“In 20 years, it (technology) is really going to be changing Hawaii. When you see what kids can do, you just feel like, ‘Wow, they’re really good.’ And you know you just have to help,” says Kitajima. “It’s kind of like our farm team for baseball. We’re building up our talent for the future.”

On average, 50 Oceanit employees mentor in the schools every year, averaging 40 hours per month. “A lot of this is driven by our people. They want to do it,” says Kitajima. “Essentially, we’ve adopted Maemae Elementary School – or they’ve adopted us – and we’ve been working with the teachers there.”

Oceanit’s total reach annually: more than 400 students, not counting the 20,000 households watching “Weird Science with Dr. V” every week. To date, Oceanit has produced 150 of the science shows that have aired on Hawaii News Now.

In its 26-year history, Oceanit has sponsored more than 250 summer internships, primarily for college students who work with company engineers on real projects.

“A lot of us went to public school,” says Kitajima, “so we’re always trying to figure out how can we help. And you help as many kids as you can because one of those kids may come up with the cure for cancer. Or the key for alternative energy or global warming.

“When we first got into robotics I was skeptical, because we don’t do it at Oceanit. Then I realized it wasn’t about robotics. We’re not building robots. We’re building future leaders. It’s just a metaphor for building thoughtful young people who will lead us into the future.”

How to Help

Want to help a school? A newly expanded website aims to make it easy to start.

The site, helphawaiischools.com, is like a matchmaker, says Judy Nagasako, DOE specialist for corporate and community partnerships.

“Schools can post their wish lists of how they need volunteers or help. And the reverse is also possible. People who want to offer something can also propose what they wish to offer to a school. The individual selects the school or schools and the message just goes to them.”

The site was a pilot project starting in 2006, but this is the first year all 286 Hawaii public schools have been listed. “We’re in the middle of training schools so they can access this information and respond to offers that may come their way,” Nagasako says.

“We’re saying (to schools) that, if you receive an offer, you should respond in a week.”

Why Help Schools? Here Are 3 Good Reasons

Before joining the Department of Education, Randy Moore spent 35 years in the private sector, including serving as president and CEO of Kaneohe Ranch, so he knows how important business support and partnerships are to public schools.

“Are they important? Absolutely, and for three good reasons,” says Moore, assistant superintendent for school facilities and support services. “One is obviously the value that is added to the school.

“The second is it’s a message from the outside community that we value the school, and that’s a message that’s valuable inside the school. Schools are a kind of bubbles that don’t have a whole lot of interaction with the rest of the world. For the folks laboring on campus, knowing that other people care what they’re doing is very reinforcing.

“And it’s good for the students to know that the outside world thinks that schools are worth supporting. The more people feel they’re doing something for the schools, it just elevates the whole community awareness of the value of the school.”

The third value shows up in the well-being of the volunteer, says Moore. “There are some interesting studies of the health benefits of volunteering. For people who volunteer there’s a specifically valid correlation between their health and their volunteer activities. Those people are healthier than those who don’t volunteer.”

Making a difference

Several programs supported by businesses have made an important difference in Hawaii’s public schools. They include:

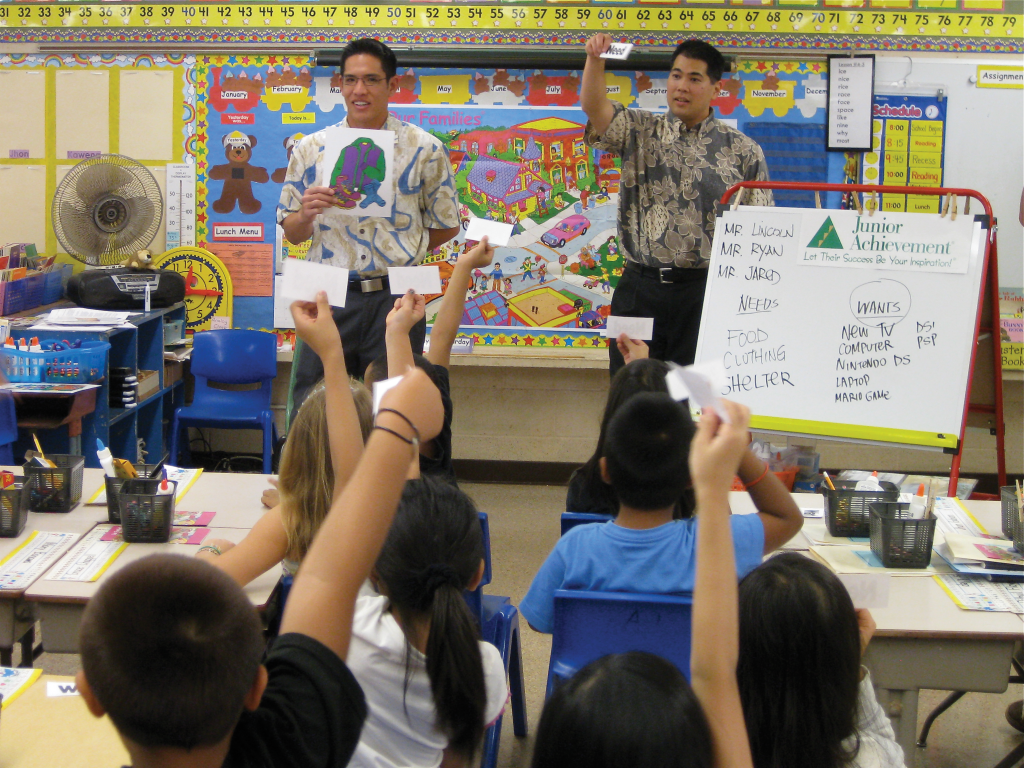

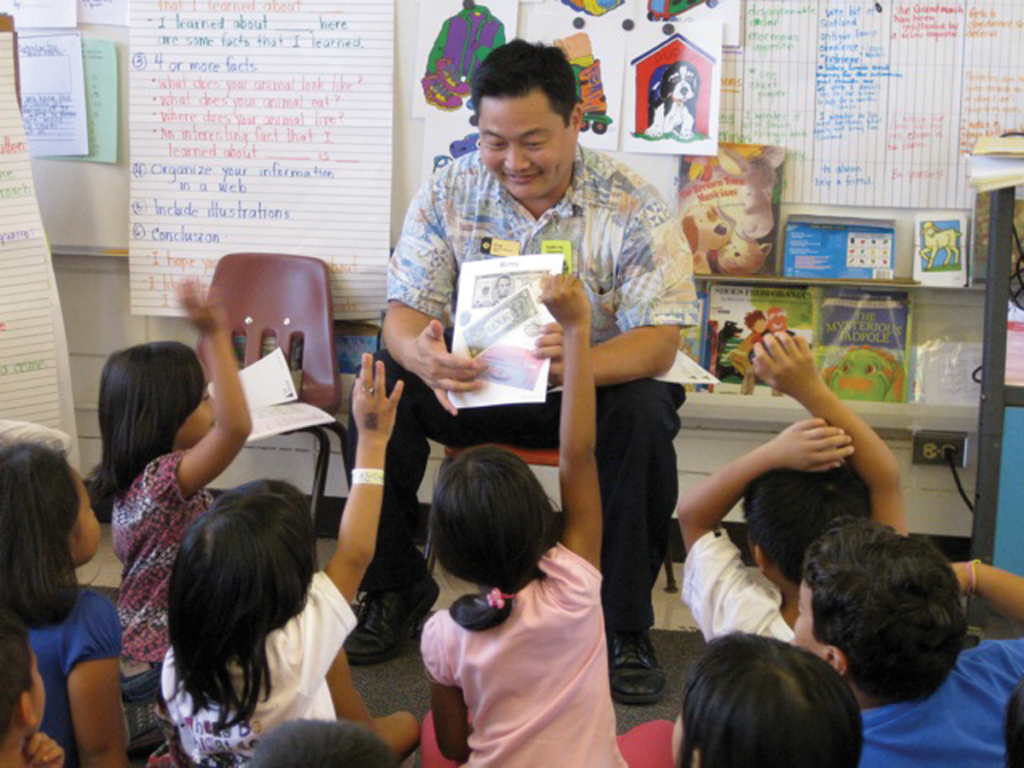

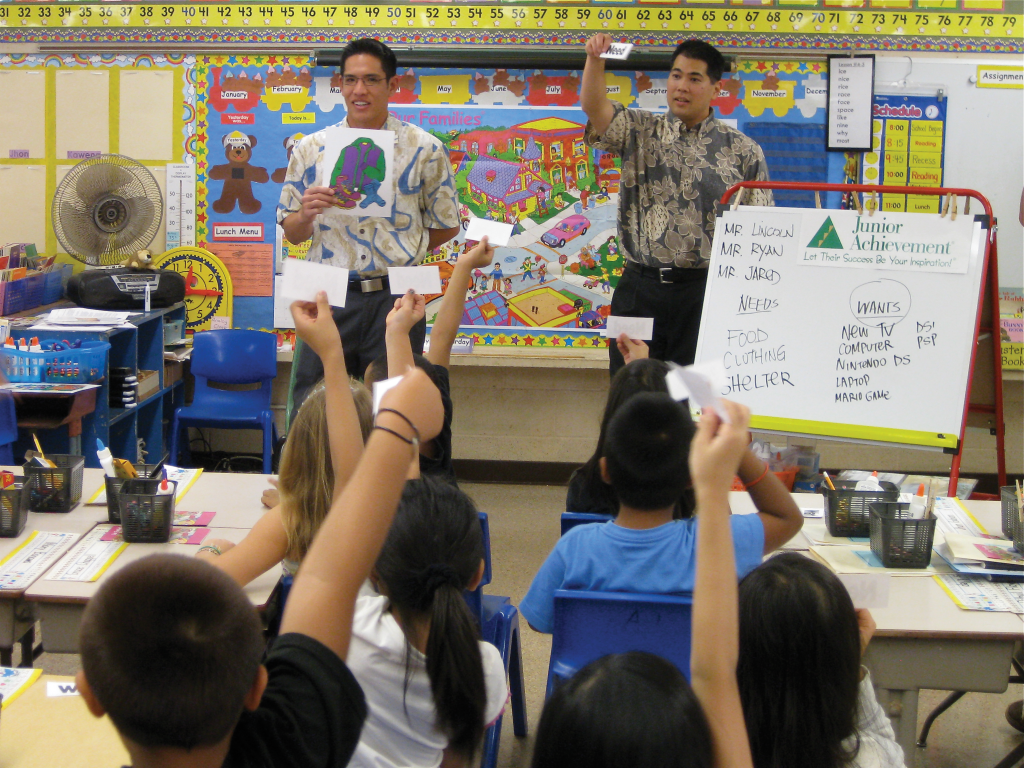

Junior Achievement

Each year, JA rallies at least 330 volunteers, most of them from financial institutions, to teach 6,500 students grade-appropriate lessons on financial literacy.

“In the fall at Aiea High, we did a personal finance program for the entire senior class,” says JA program manager Arlene Kihara. “We talked about things like budgeting, investing, credit, identity fraud and insurance. (Otherwise) they don’t get that in school.”

Oahu Workforce Investment Board

The city’s board partners with business in many ways, including bringing 30 or 40 business leaders to Roosevelt High annually for an intensive career day for the junior class.

Hawaii 3Rs

The program’s name stands for repair, remodel and restore public schools and was launched by U.S. Sen. Daniel K. Inouye in 2001. Since then, it has completed projects worth $39.6 million at 186 schools.

Federal and state money covers half the costs and primes the private-sector pump, which has turned out 3,300 volunteers, who donated 13,000 hours of free labor.

Dozens of businesses have contributed and Realtors and staff from Prudential Locations are among the most stalwart, says executive director Ryan Shigetani. The Realtors do two projects a year and donate $5,000 for each project. They recently restriped the parking lot, curbs and some walkways at Pauoa Elementary.

“A lot of companies are looking for team building and community involvement, and leaving a mark on a school,” says Shigetani. “What has made our projects a little higher quality is we hire contractors as well. The federal and state money allows us to have a higher standard and it also makes the work our volunteers do more efficient.”

As an example, he cites a project a couple of years ago for which Central Pacific Bank fielded more than 100 employees to paint Dole Middle School. Shigetani used government money to hire contractors to prep the walls first so volunteers could move quickly and effectively.

“We did it in a day. The entire campus,” he says.

With earmarks all but dead in Congress, Hawaii 3Rs has an uncertain future.

“The future of our program is in doubt right now,” said Shigetani. “We’ve raised over a million dollars privately, but, in the future, it’s going to have to be more. With the lack of earmarks we’re going to have to revamp our program.”

Hawaii 3Rs (A)Rithmetic

Federal funding for the 3Rs program is in jeopardy. Here’s where the money comes from:

Where to sign up as a volunteer

Junior Achievement

545-1777, www.jahawaii.com

Hawaii 3Rs

521-5524, www.hawaii3rs.com

Public Schools of Hawaii Foundation

943-1622, www.pshf.org

Oahu Workforce Investment Board

527-5166, www.honolulu.gov/dcs.owib/