Building Guam

Will Hawaii profit from the boom?

When the U.S. and Japanese governments announced plans in 2006 to move nearly 8,000 U.S. Marines and 9,000 dependents from Okinawa to Guam, they set in motion what may become one of the largest building booms of this era. Big Hawaii construction companies are already planning for this enormous buildup, which is expected to take more than five years. Smaller Hawaii contractors can also get a lucrative piece of the action, but only if they are willing to take on risks and a learning curve.

The military realignment will make the island of Guam, America’s westernmost territory, the vanguard of U.S. forces in Asia. The undertaking is enormous. Simply accommodating the arrival of the Marines, for example, will require the construction of everything from enlisted and officers quarters, to support and training facilities, to gyms and recreation centers, to infrastructure like roads, sewers, potable water plants and communications facilities.

The relocation of the Marines is only part of the story. Military development in Guam will also include missile defenses, docks and support facilities for an aircraft carrier, and substantial increases in Air Force and Coast Guard operations. In all, NAVFAC Marianas — the entity coordinating all the work — expects to spend at least $14 billion, nearly a third of which will be paid by Japan.

Strategic Partnerships

In Hawaii, the most likely beneficiaries will be the large military contractors – dck pacific, Actus Lend/Lease, Kiewit Building Group, Watts Constructors, et al. – many of which already have experience in Guam. But even these companies will be dwarfed by the work. Getting it done will require unprecedented partnerships. Because of the scale, most contractors expect NAVFAC to use a form of procurement know as Multiple Award Construction Contracts. Under the MACC process, probably only four or five teams of contractors will even qualify to bid. Given the size and variety of the projects – NAVFAC says they’ll range from $15 million to $300 million – successful teams will need to demonstrate many skills.

“You’re at risk here. It’s not for the faint of heart.”

– Denny Watts, president, Watts Constructors

According to Denny Watts, president of Watts Constructors, and perhaps the dean of Hawaii-based contractors in Guam, finding the right strategic partners is key. “We’ve been going through that for the last year,” he says. “We’ve talked to maybe 25 of the best organizations in the world to determine who we want to be partners with for the long term.

“We’re looking for partners with competencies in things that maybe we aren’t as strong at. That’s because these contracts will vary between sophisticated marine projects, to technically complicated infrastructure, to basic living quarters. Your team has to show expertise in all those capabilities.”

To complicate matters further, the bidding process has to be precise. “These are all hard-bid, hard-number contracts,” Watts says. “It’s not like in the Middle East where they were cost reimbursable. You’re at risk here. It’s not for the faint of heart.”

Even before the buildup for the Marines, Hawaii contractors like Watts Constructors have been working on military projects in Guam. | Photos: Courtesy of Watts Constructors

Labor Pains

Many of the most nettlesome problems facing contractors revolve around workforce management. “There are only 2,000 to 3,000 construction workers on the island presently,” says Roger Peters, general manager of dck pacific. “At peak, they feel there will be the need for 25,000 to 30,000 construction workers. So, the challenge is: Where do you get that many skilled workers?” Of course, with a population of about 170,000, labor shortages have long been a problem for Guam. “Traditionally, what’s been done is they bring in labor from the Philippines,” Peters says. At this scale, though, he notes that may not be adequate. “I think you’re looking at a global supply: Filipinos, Indians, even Mexicans.”

Perhaps more critical than finding skilled labor is identifying the foremen and supervisory staff to manage them. Companies like dck pacific and Watts Constructors, which have been working in Guam for years, already have trained crews and experienced supervisors, though not nearly enough to handle all the new work. Other teams will likely have to bring in most of their foremen and supervisors from off-island. Recruiting these positions for Guam has always been difficult. Even Hawaii workers have historically been reluctant to relocate to Guam. But companies like dck pacific will have to persuade them. “That’s not just Hawaii, either,” says Peters. “We’re offering these opportunities to people in our home office in Pittsburgh, to people in Atlanta, even to people in the Caribbean.”

Finding the workers is just the beginning. The MACC bidding process also requires the contractor to plan for their accommodation. “You have to explain how you’re going to house them, feed them, entertain them and care for their health,” Peters says.

Some Hawaii companies like BASE and dck pacific have already worked together on major projects like school construction in Guam. | Photo: Courtesy of BASE

Logistics

From a contractor’s perspective, the most obvious feature of Guam is its remoteness. At 5,900 miles from California, and nearly 3,800 miles from Hawaii, Guam lies at the end of a long and tenuous supply chain. “Most of this work is ‘Buy American,’” says Peters. This means construction material can’t be quickly shipped from nearby Asian suppliers, making it critical to understand materials logistics. It takes a ship three weeks to get from the West Coast to Guam. “So, you’ve got to be self-sufficient,” Peters says. “When something breaks, you better have a spare part, or you better be able to get a replacement quickly – probably by airfreight.”

Even within Guam itself, logistics will be challenging. Port facilities will need tens of millions of dollars in improvements to handle shipping volumes, which are expected to quadruple. Roads and bridges will have to be hardened and widened to accommodate the trucks needed to haul material. There’s not enough electricity or fresh water to supply the anticipated needs. And there’s nowhere near enough warehouse space from which to stage the enormous construction projects. Once it gets started, the great Guam buildup might turn into a quagmire.

Small Businesses

Despite the challenges, Guam still represents a tremendous opportunity for large Hawaii companies. For smaller Hawaii subcontractors, the labor issue presents a major hurdle. “They’ve never had to go out and hire foreign workers,” Denny Watts points out. “And yet, by definition, these are the guys who would have to provide 75 percent to 80 percent of the manpower on any given job.”

“There’s other infrastructure work that we can get involved in. It might be housing, upgrading the local schools or building bridges. But the first step is to have a more solid and continuous presence.”

– Steven Baldridge, president, Baldridge and Associates Structural Engineering

“I know there are several sub-contractors interested in coming to Guam,” Peters says, but he doubts they’re pre-pared to work with an inexperienced workforce. “When you need 30 electricians, you can’t just go down to the union hall.” Maybe more important, he points out that not knowing the productivity of your workforce makes it impossible to budget accurately. “Productivity drives your construction costs,” he says. “And understanding productivity determines what you bid.” In short, it’s almost impossible for small companies to plan adequately for Guam.

And planning is essential. Lance Wilhelm, senior vice president of Kiewit, points out that his own company, a major U.S. contractor, is still grappling with the implications of going to Guam. “Businesses need to formulate a Guam strategy, whether you’re big or small,” he says. But small companies in particular have to look at what it means to do business so far away. “How are you going to manage your people? Do you even have the people who are willing to go down there? How will you handle the logistics? Do you understand the tax issues, union issues, legal issues … ” Small companies need to consider all this before they talk with the larger contractors. “You need to formulate a strategy,” Wilhelm says, “so, if you should be asked to go down there, it isn’t the first time you’ve thought about those things.”

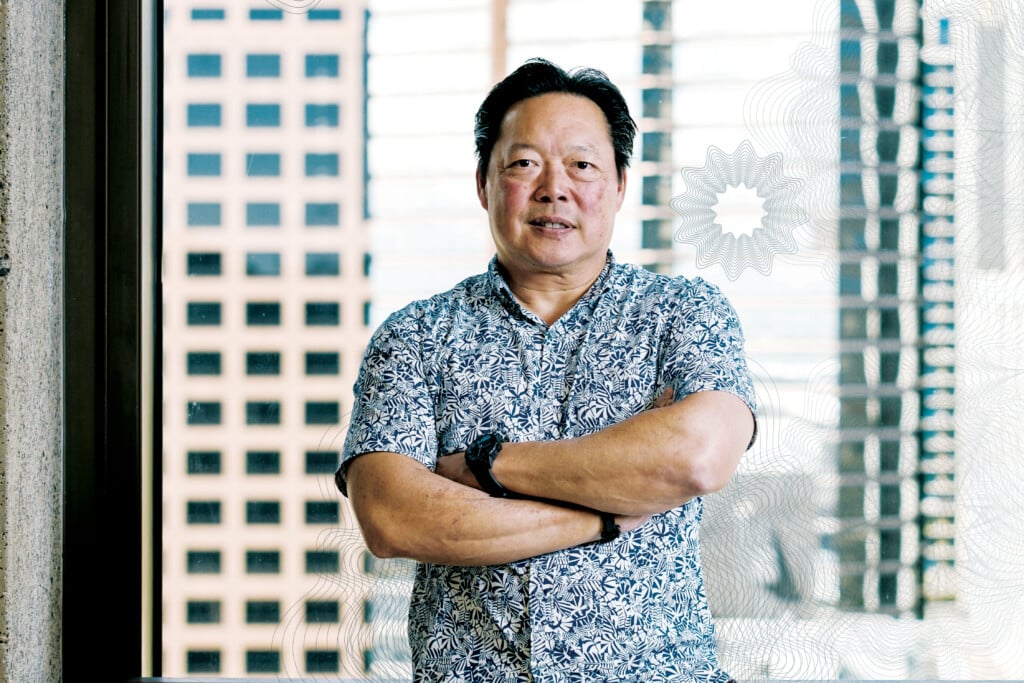

Steven Baldridge, president of Baldridge and Associates Structural Engineering. | Photo: Rae Huo

Wilhelm also points out that, for many small companies, management is already stretched thin. “Can you commute to Guam and still keep a going concern here in Hawaii?” he asks. “We’ve had to think about that, too. We’re not going to jeopardize what we have here in Hawaii; so, part of our Guam strategy is that we have to be able to do both.”

Notwithstanding the complications, small Hawaii companies will almost certainly be drawn to Guam. Many of them already have experience there. Steven Baldridge, president of Baldridge and Associates Structural Engineering, points out, “We’ve actually done work in Guam for about 10 years; we’ve just done it from Honolulu.” Most of BASE’s work in Guam has been for the military, which can often be done from a distance. But, like many observers, Baldridge expects the buildup to also generate work “outside the fence.” That may be where small Hawaii companies, particularly technical companies and vendors that are less burdened by labor issues, will find their place in Guam. “There’s other infrastructure work that we can get involved in,” he says. “It might be housing, upgrading the local schools or building bridges. But the first step is to have a more solid and continuous presence.” For BASE, the Guam office is about becoming part of the territory’s business community.

That process is made easier by having Hawaii service providers already working there. It’s possible, for example, for a Hawaii company to open an office in Guam and still use the same bank, accounting firm and law firm as the home office. Many of these companies are important members of Guam’s business community. First Hawaiian Bank, for example, is the largest bank in Guam. Carlsmith Ball has had law offices there for more than three decades. Because of this experience, they offer more than just banking and legal services; they provide inside knowledge of the community and vital introductions.

“Remember, the cake is the island of Guam itself; the buildup is only the icing.”

– Don Horner, chairman, First Hawaiian Bank

Hawaii companies are already taking advantage of the Guam buildup. “We’re getting calls from customers almost every day,” says Ray Ono, vice chairman of First Hawaiian Bank. “They’re hearing more and more about the potential in Guam, and they’re calling for information, just trying to validate what they’ve been hearing elsewhere. They’re doing their due diligence, calling their banker – who happens to have a stable operation in Guam and has been there nearly 40 years.”

“We have some old hands here in terms of Guam experience,” says Dean Robb, an attorney at Carlsmith Ball. Robb himself has been working in Guam since the 1970s. “And, if you walk down our halls,” he says, “there are probably seven or eight lawyers here who also practice in Guam.” Perhaps more importantly, the Guam office of Carlsmith Ball is staffed almost entirely with local Chamorro attorneys.

Investing in Guam

For small companies that take the time to learn about the community, a whole new class of opportunities arises – opportunities that have less to do with the buildup and more to do with the development that it causes. Companies like PEMCO or Commercial Roofing and Waterproofing may have gone to Guam to pursue military or government work, but, in the end, they’ve invested in Guam itself. John Yamamoto, president of PEMCO, notes that, in addition to his company’s bread and butter, managing foreclosed properties for HUD, they now have a joint venture with a landowner in Guam, investing millions of dollars in housing in anticipation of the island’s growth.

CRW has taken a similar path. “We’re making money,” says company president Guy Akasaki, “because we have some military projects.” But he proudly notes that the centerpiece of his company’s investment in Guam is 12 acres it has purchased in the industrial area of Harmon. This kind of site will be critical when contractors need staging areas for their immense projects.

First Hawaiian chairman Don Horner, who’s long had an interest in Guam, has the same view. He notes that much of First Hawaiian’s success there comes from treating Guam not like some foreign adventure, but like a Neighbor Island. He points out that you can get all the services of the Bishop Street headquarters at any Guam branch. And he uses an interesting metaphor to advise small companies considering the move to Guam: “Remember, the cake is the island of Guam itself; the buildup is only the icing.”