Building for Climate Change in Hawaii

Rising seas and other effects of climate change are changing the way buildings in Hawaii are designed and constructed. In this two-part report, we look at what the building industry is already doing and should be doing, plus some ways it’s trying to reduce its own impact on the environment.

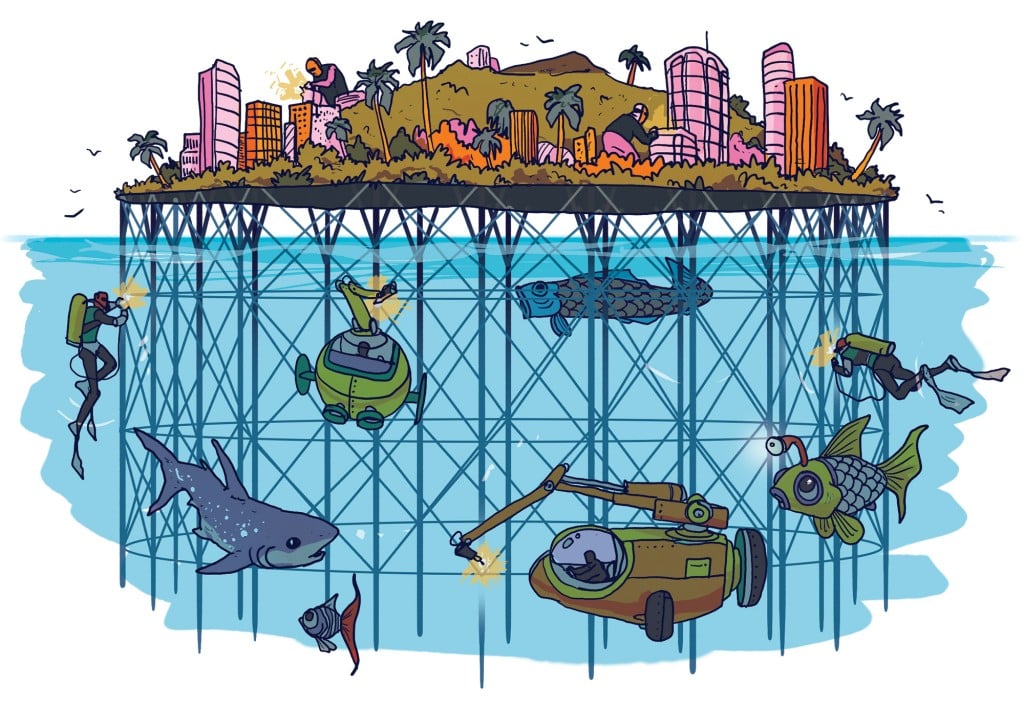

Illustration by Michael Byers

Part I: Building for Climate Change

Climate change is here. Hawaii is already experiencing warmer temperatures, sea level rise, more flooding and more intense rainfall and tropical cyclones – and it’s going to get worse in the future.

Scientists say Hawaii needs to start preparing for this new world, starting with the building industry. Already we’ve seen individual structures built to survive natural hazards that might be exacerbated by a changing climate. But scientists and some people in the industry say a holistic approach is needed – beginning with government regulations covering how we should build for climate change.

“All of our engineering and our architecture and our designs of our community came into existence under a climate that no longer exists,” says Chip Fletcher, a geology and geophysics professor at UH Manoa. “So we are out of date, out of nature’s code, and all of that translates into less resiliency.

“And I define resiliency as you can’t stop a hurricane, but you can come back from it faster and you can experience less damage if … you build with the expectation that you will get hit with a hurricane.”

Climate is Changing

Scientists project the sea could rise up to 3.2 feet by 2100, if not sooner, flooding 6,500 structures in the Islands and displacing nearly 20,000 residents, according to the 2017 Hawaii Sea Level Rise Vulnerability and Adaptation Report, prepared by Tetra Tech and the state Department of Land and Natural Resources.

But before the sea reaches that level, the Islands will experience more frequent temporary flooding from king tides – seasonal high tides that typically occur in June/July and December/January – likely within a few decades, says Fletcher, who is also a member of Honolulu’s Climate Change Commission. The commission’s five members collect information and provide advice to the county government as it plans for climate change.

Hawaii can also expect to experience more heavy rainfall, like the 49 inches of rain that fell in Hanalei in 24 hours in April, hotter temperatures and more frequent tropical cyclones. These cyclones tend to be more frequent in El Nino years, when water warms in the Pacific. Cyclones don’t hit Hawaii often, but as the climate warms, more storms might strike the Islands.

“All of our engineering and our architecture and our designs of our community came into existence under a climate that no longer exists.”

-Chip Fletcher, Geology and Geophysics professor, UH Manoa

These hazards and others associated with El Nino – such as extreme coral bleaching and lack of trade winds – are expected to double in frequency.

“At the same time that the building industry needs to re-examine their exposure and their vulnerability to hurricane storm surge, they should re-examine their vulnerability to heat waves, to flooding of the storm drains and the groundwater,” Fletcher says.

The big question, he says, is: “What are the design elements that we should adopt now that make us most resilient and sustainable in light of the fact that we’re living in a new world, a new climate?”

Complicated Task

Sea level rise is the first climate change impact that residents are waking up to, Fletcher says. The Climate Change Commission recommends that the county plan for frequent high tide flooding by mid-century and at least 3.2 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century. Because global greenhouse gas emissions are increasing, large projects with long lifetimes should plan for 6 feet of sea level rise by 2100 and beyond.

Climate change and sea level rise are already being incorporated in some of the county’s planning, such as in the proposed updates to the General Plan, the county’s long-range planning document, and the county’s Land Use Ordinance, which defines zoning districts and sets development standards for each one. The updated General Plan is awaiting approval by the county council, and the updated Land Use Ordinance is still being drafted.

“The language very often is aspirational – that we will take into account these hazards and build to be more resilient. But I think at this stage, we need to increase the detail. We need to get down into the weeds with regard to specific architectural design, specific engineering, re-engineering designs,” Fletcher says, adding that the general plan updates for Kauai and Maui counties also mention climate change.

Kathy Sokugawa, acting director of the Honolulu County Department of Planning and Permitting, says many people in the building industry and in government are still looking for more definitive data. There’s a general sense of what Hawaii will face in the next 50 to 75 years, but there’s disagreement about whether the state should plan for 3 feet or 6 feet of sea level rise because the specific impacts are not yet well known.

How the building industry builds for climate change depends on the regulations the government creates, says Dean Uchida, 2018 president of the Building Industry Association of Hawaii, whose 375 member businesses include general contractors, suppliers, real estate agents, engineers and architects. For sea level rise, government rules could regulate whether to harden the shoreline, gradually move communities away from impacted areas or elevate structures.

“Generally, government would set the standard and then designers would kind of follow,” Uchida says. “It’s hard to design for climate change if you don’t know what the standards are going to be for government.”

In July, Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell signed a directive that required county departments and agencies to take action to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change and sea level rise. The directive was a response to guidance issued by the Climate Change Commission, which recommended the county plan for 3.2 feet of sea level rise by mid-century.

Departments will need to rely on this guidance when viewing proposals and making capital improvement decisions, and incorporate it into future regulations, setbacks, laws and codes, such as the building code. “I think taking action now will result in a better future for all of us,” Caldwell said.

Bettina Mehnert, president and CEO of Architects Hawaii Ltd. and a member of the Climate Change Commission, says it’s a great step forward that the draft updates to the Land Use Ordinance – which works in conjunction with the county’s building code – will address climate change and resiliency for the first time. In June, Gov. David Ige signed a law that requires environmental impact statements and assessments to include an analysis of sea level rise.

“That truly gets me excited that we’re moving in the right direction,” Mehnert says. “Fast enough? It remains to be seen.”

Within the building industry itself, she sees baby steps. Emergency generators are not located on the ground floor anymore, and some new buildings are elevated, like the Aeo condo tower in Kakaako. Aeo was one of AHL’s projects and was elevated to meet a requirement for building in a flood zone, but, she says, it’s an example of how the solution for one problem could help with another.

With no requirement for how the built environment will react to sea level rise, the responsibilities of dealing with climate change lie with building developers and owners, Mehnert says, adding that the Climate Change Commission is tasked with facilitating the discussion toward a resolution.

“It’s very hard to say this is what we’re going to do to fix it, because it is so complex and because there’s such delay in seeing the results,” she says, adding that building owners would be making a big financial commitment now, with no payoff for decades, “and that would be hard.”

Flexible Design

Gary Chock, president of structural engineering firm Martin & Chock, says building for climate change doesn’t have to be controversial or unfeasible if one uses adaptive engineering. That means building flexibility into designs so buildings can be modified to account for future climate change effects. An example would be building a flood control wall or revetment with a foundation stable enough so the wall atop can be built taller later, if needed.

He says this approach doesn’t require a fundamental change in how facilities are designed; it’s just another factor to consider. That’s different from building for the worst-case scenario 75 years in advance, which, he says, is a difficult argument to make because it would be expensive and there’s still uncertainty about what the future climate will look like.

Photo: Aaron Yoshino

King tides at Waikiki Beach reach this walkway.

He adds that one thing to consider is that climate change is not a hazard onto itself: “It’s something that affects the severity of the future hazards, whether it’s flooding, hurricanes or so forth, all of which we design for today. If you have some enhancement of your design today for, say, flooding or hurricane winds or whatever, you’re actually building into that mitigation of future possibilities. So what we do today should make sense regardless of that degree of uncertainty in the future.”

Chock says he hasn’t seen this adaptive engineering approach used yet in Hawaii because it’s a fairly new recommendation – one that came out of his September 2017 report that looked at state and county building and development regulations to determine if they might need future adjustments to accommodate climate change effects.

Some other recommendations included revising the shoreline setback rules to base variable setbacks for new construction on historic erosion rates, and revising the wind speeds and amount of rainfall that critical and essential facilities would need to be built for under the county’s building code. Critical facilities are structures that represent a hazard to human life if they fail, like buildings where more than 300 people congregate; essential facilities are buildings such as hospitals and emergency shelters.

In addition, Chock says, the state needs to adopt a more modern building code. The current code is outdated and based on the 2006 International Building Code. “In order to get to the future, we have to update at least to the present, and that gives us the foundation or the springboard to get to the future,” he says.

Mehnert adds that while government rules and regulations set the baseline standard for the building industry, the industry constantly looks for solutions to address new challenges. After all, each project has a team of architect-led experts that design for the specifics of each site.

Fletcher says now is the time to design for the future.

“The design industry, architecture, engineering industry … have to become their best selves, have to find their milestones of excellence with regard to public safety, public sustainability, because this is going to be a challenging time.

“But if everybody is on board and if everybody keeps climate change as a front and center focus to their professional work, I believe we can actually thrive under this changing climate.”

See the impact of rising seas

At the Hawaii Sea Level Rise Viewer, you can see a simulation of the impact of various sea level increases: 0.5 feet, 1.1, 2.0 and 3.2 feet. View the Sea Level Rise Viewer here.