Broken: Stuck in Permit Purgatory

George Atta, director of the Department of Planning and Permitting and a former principal at the architectural firm Group 70 international, knows just how swamped Honolulu’s permitting system is.

Hideo Simon can barely contain his frustration.

“It took me six months,” he says, “just to get my building permit for this place.”

We’re speaking in Square Barrels, his new restaurant in Bishop Square, and he has to raise his voice to be heard over the hubbub of the crowded dining room. It’s a bright, modern space, with tall ceilings and a row of high-backed booths against the wall. Behind the bar, a rank of unmarked taps dispenses two dozen varieties of beer.

The stylish restaurant, Simon says, is the culmination of his lifelong obsession with gourmet burgers and craft beer, a taste that’s clearly shared by the downtown Honolulu crowd. The place is packed for Wednesday’s lunch hour. But, according to Simon, Square Barrels almost failed before it started, nearly done in by the City and County of Honolulu’s byzantine system for issuing building permits.

The problem, he says, is it’s just too complicated and time-consuming to get even a basic building permit. An application, particularly for a commercial project, may require a handful of departments to sign off. In addition to the review at the Department of Planning and Permitting, it may need to be stamped by the fire department, the Board of Water Supply, wastewater and elevator officials, the State Historic Preservation Division, et al. Navigating this process, Simon says, can be complex. And he’s no neophyte. In 2012, he and his partners opened Pint + Jigger, a successful King Street gastropub that also stumbled its way through the permitting maze, so Simon knew what he was getting into. This time, he even hired Bureau Veritas, one of the city’s so-called third-party reviewers. These are city-certified private companies that officially review plans for building code compliance, and then act as expeditors, helping shepherd permit applications through the other departments that need to sign off. But, according to Simon, even with a third-party reviewer, the process was painfully slow.

“It’s ridiculous for the city to expect you to hang tight for six months.”

— Hideo Simon, Co-owner, Square Barrels restaurant

“Just for one person to sign off,” he says, “it takes at least a couple of weeks of review from each department. And that’s on top of the time it takes for the third-party review. So, I go to the third-party reviewer and they make their comments. Then, they take the plans to the DPP, and it comes back with notes. Then we get the architect to change the notes. Then it goes back to DPP and they say it needs more notes, and blah, blah, blah. Each and every step takes a month, it seems like. And I don’t even know which department needs to sign off on every one of these bits.”

All of this costs money, Simon says. The owners must pay for the permit, fees for the third-party reviewer, costs for a draftsman or architect to change the plans, plus rent and salaries for key employees while they wait for the restaurant to open. Most important, the business owners forego any income until the permits are approved and the actual construction is finished. It’s just too much to expect for a small-business man, Simon says.

“The reality is I built this place before I got the permit for it. I didn’t get my permit until three weeks after I opened the doors. If a building inspector had come by, he could have easily pulled the plug on the whole thing and I would have been hanging in the wind. I would be bankrupt. It’s ridiculous for the city to expect you to hang tight for six months.”

Simon’s story isn’t unique, of course. What sets him apart is that he’s willing to speak on the record about his permitting problems (to the chagrin, he says, of his wife and partner, Grace Simon). Most business owners won’t, fearing reprisal the next time they need a permit. That’s what makes it so difficult to report on the problems at DPP. But almost everyone knows a business owner, contractor or home builder with a nightmare permitting story to tell – a tale of applications lost in the system, of inspectors who never show up, of a seemingly endless succession of delays. But, absent more business owners willing to come forward, like Simon, it’s difficult to document how widespread the problem really is, or whether the blame lies with reviewers at DPP, or with applicants themselves.

Not everyone thinks DPP is doing a bad job. Heidi Levora, whose family owns Anchor Systems Hawaii, a foundation contractor, says she’s been successfully running permits for several years and has developed a rapport with the people at the department.

“So far, we’re not making much headway. All the measures we’ve taken just have us treading water” because of the boom in construction.”

— George Atta, Director, Honolulu Department of Planning and Permitting

“It’s nice to be on a first-name basis with these folks,” she says. “Sometimes they’ll engage in creative problem solving with me, which saves a trip back and streamlines the process greatly. I have not witnessed any favoritism at all, ever. They really try to make the system as fair as possible. I do see staff responding more warmly toward calm, pleasant individuals. That’s human nature.”

So, how do we resolve the differing experiences of Simon and Levora? How do we get beyond the inevitable contradictions in this kind of anecdotal evidence? Maybe the best approach is to look for honest brokers within the system itself.

SOURCE OF THE PROBLEM

One person with an interesting perspective is George Atta, a former principal of the architectural and design firm Group 70, and now the director of Honolulu’s Department of Planning and Permitting. As someone who’s been on both sides of the permitting counter, Atta isn’t shy about addressing criticism of the department.

“The standard complaint,” he says, “is that the review time takes too long. I would say that’s a valid complaint most of the time. The process does take a long time. Sometimes, that’s our fault. Sometimes we assign the review to a person who doesn’t follow through. Sometimes we have bad apples who will hold on to the permit. We don’t have a good enough supervisory system set up, so, whether out of intent or negligence, the permit gets held up. We often don’t know it at the upper management level until the customer complains. So, sometimes the problem employees end up holding permits for some time.”

But that’s not the whole story, Atta says.

“Other times, the fault is with the people preparing the plans. We have some people who we call ‘rubber stampers’. These are architects and engineers that will do things on the cheap.”

By that, he means they either create rudimentary, low-quality plans, or they stamp the unprofessional or incomplete plans of their clients with their own seal of approval and submit them for review at DPP.

“Our guys will red mark them and send them back,” Atta says. “What these rubber stampers are doing is using our staff for quality control rather than having good plans up front.” This takes additional time as plans go back and forth for comments and corrections. But that was the intention all along. “So the rubber stampers don’t complain, but their clients complain. But they just tell them, ‘It’s stuck at DPP.’ So, many times, our staff gets blamed because you end up going through multiple review cycles, and that takes time.”

However, Atta attributes most of the growth in permitting delays to the changing nature of regulation itself.

“Over the years, land-use regulations and building codes have become much more complex,” he says. “For example, historic site reviews never existed before. In the 1950s and 1960s, they didn’t have to go through NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) reviews. They didn’t have to send their reviews to design access boards for American Disability Act compliance. That came in the late 1980s. Before that, they didn’t have to go through those compliance reviews. Every year, new things like these come up – new things to review. The building code back in, say, 1929 was only an inch thick. You could carry it in your back pocket. Today, you have a two- to three-foot stack of binders. The sheer volume of regulation has increased dramatically, and every one of those regulations has added complexity and additional time to the process. That has been a large factor in slowing things down.”

SOLUTION

So, how should we address these problems? In a sense, DPP itself was created to help solve them. Getting a building permit used to mean running all over town. Each step in the process required a visit to a different agency. To simplify things, most of the agencies involved in permit reviews underwent a kind of roll-up.

“The DPP is the consolidation of three whole departments and parts of two other departments,” Atta says. “One was called the Department of General Planning; another was called the Department of Land Utilization; and the third was called the Building Department. But, in 1998, under Mayor (Jeremy) Harris, these three were consolidated into one, much larger, department. Then, to consolidate all the permitting functions, they also brought in the wastewater branch, which issued sewer permits, and also Public Works site development, the civil engineering investigative body.”

This consolidation didn’t solve all the problems – applications still have to make the rounds at several different agencies – but it at least put them mostly under one roof. In theory, that should make the process more efficient.

That’s not all DPP has done to address the permitting issues. In addition, Atta says, the department has tried to make it easier to get permits for simple projects.

“For example, we’re making it so you can get some permits online; it doesn’t have to come through staff review. PV panels, for example, can be permitted online. You fill in a form, pay a fee with a credit card and print your permit. … This works for the projects that have a fairly standardized process. For these simpler projects, we’re trying to either put them online or use counter permitting. So, for things like fence permits and driveway permits, we’re saying the clerks up front can issue those. Hopefully, that can help eliminate the backlog.”

“The other thing we’re working on,” Atta says, “is something called the ‘one-time review.’ One of the things that delays projects is having multiple cycles of review. Plans are red marked and sent back to the designer several times. Over the years, reviewers have gotten into the habit of (using this approach to catch mistakes). My guys have just gotten used to doing it that way.”

The problem is that this can turn into a longwinded back and forth between designers and reviewers. One-time review was created to short circuit this cycle, Atta says.

“I tell my guys, ‘Now, you only have one bite at the apple. Make all your comments once rather than use multiple cycles of review.’ That forces our guys to do a thorough review up front. Then, after the applicant makes the changes, the next time we just do a cursory review. My guys are unhappy because they know they might miss things. If they have multiple bites of the apple, they’re less likely to miss anything. I tell them, ‘If you miss anything, the inspectors out in the field will catch it.’ ”

But this approach butts up against another problem for the department: There aren’t enough inspectors. Simon, for example, complains of waiting weeks for the follow-up inspections necessary to close his permit. In fact, the manpower shortage is a problem throughout DPP. Dennis Enomoto, owner of the third-party reviewer Palekana Permitting and Planning, traces the human resources problem back to the reorganization of the department.

These land-use-plan checkers, with their newly created authority, have become the linchpin of the permitting system for the county.

“What happened was they had a hiring freeze, way back in Mayor Harris’ time. I don’t want to dis what they did, but they reorganized the department and they had a hiring freeze. I think that created a staff shortage as well as – I don’t know what you’d call it – an experience shortage. Now, for the last several years, a lot of the 30-year veterans are retiring. And, since they weren’t hiring people, you don’t have all these backfills.”

Still, Enomoto attributes 85 percent of the problems at DPP to the quality of the plans people submit for review. “Everybody disses on the guys and complains a lot, but, to me, there’s a lot of good people over there. Ninety-five percent are just trying to do a good job. But the basic responsibility for the building permit is that they’re a regulatory agency. They say, ‘You’ve got to do it like this,’ but people don’t want to hear that. They go out of their way to tell them how to do it, but customers still get upset.”

Even while acknowledging the human resource shortage is a problem, Atta, too, subtly shifts the responsibility to the applicants.

“During the height of the PV boom,” he says, “we sometimes had months when the inspectors couldn’t come out to close the permit. But now, with one-time review, the inspectors will have to catch things, if the plan checkers don’t catch it. My guys don’t like that. I try to remind them that our job is protecting health and safety issues, but, at the end of the day, the liability rests with the contractor. The permit is not a guarantee that everything will be up to code and that all the regulations are enforced. After all, even if the drawings are correct, construction may not follow the plans, maybe in order to save money. But my guys are still unhappy with not getting multiple bites at the apple.”

“During the height of the PV boom,” he says, “we sometimes had months when the inspectors couldn’t come out to close the permit. But now, with one-time review, the inspectors will have to catch things, if the plan checkers don’t catch it. My guys don’t like that. I try to remind them that our job is protecting health and safety issues, but, at the end of the day, the liability rests with the contractor. The permit is not a guarantee that everything will be up to code and that all the regulations are enforced. After all, even if the drawings are correct, construction may not follow the plans, maybe in order to save money. But my guys are still unhappy with not getting multiple bites at the apple.”

Of course, another attempt to speed things up at DPP was the institution, in 2006, of the third-party review system. A summary of how that system works highlights both the complexity of the permitting process and its basic rationale. Enomoto walks us through the process when clients come to Palekana for help:

“We take their plans and try to go through them real quick to make sure the major elements are there. Then, we schedule up. We go down to the Building Department at DPP, log it in and start the routing process with the city. You actually have to go to the city and sit down with staff and they go through the plans and they see who all needs to look at the plans – zoning, Board of Water Supply, sometimes the State Historic Preservation, sometimes elevator. Then, they create this routing. They have to physically log it in. They have certain stamps that they have to put on the plans; that’s the log in. Then, you officially get an application number. That puts you in the queue. Then, based on the routing, you can start taking it around to the various agencies for review and approval.”

Concurrently, he says, Palekana consultants are reviewing the customer’s plans for code compliance. “More than likely, that would be building – that’s for almost everything – electrical, mechanical and sometimes structural.”

Then, Enomoto says, the third-party reviewer begins to run the plans by the different departments on the routing list. “In this process, we generate comments, and the city agencies generate comments as well, and then we send those to the design team to respond. So, they make their corrections and eventually we get the approvals from everybody. We consolidate the sets, take them back to the Building Department, which does a quick review to make sure everything is in place, all the routing gets signed off and then they issue what they call an ‘approve to issue notice.’ Then, the contractor can take that and go down and pick up his permit.”

As complicated as third-party review sounds, Enomoto says it works well most of the time for Palekana. “For some of the simple projects, we take four to six weeks or so, versus three to four months” without third-party review.

But Enomoto is less sanguine about another method DPP introduced to speed up things: ePlans, a computerized system that, as the name suggests, was supposed to allow designers to file plans electronically.

“Everybody disses on the guys (at DPP) and complains a lot, but to me, there’s a lot of good people over there. Ninety-five percent are just trying to do a good job.”

— Dennis Enomoto, Principal, Palekana Permitting and Planning

“That’s not going well,” he says. “It’s a computer system that requires very specific formatting and that kind of thing. You know how it is: garbage in, garbage out. The system requires you to submit things really precisely, so it’s hard. Everybody messes up and that causes delays. Again, the city is busy, so it cannot get to the corrections right away, so that causes a lot of problems.”

Even strong advocates for DPP, like Heidi Levora, say the city’s digital effort falls short.

“I’ve heard the ePlan program is hard on the inputer’s eyes,” she writes. “If they hit one wrong key, everything they’ve been working on can disappear. They can’t be interrupted, which means even easy-to-answer questions have to wait. I sure hope, for their sakes, they get a more user-friendly program soon.”

Like many permit applicants, Levora says she still prefers the face-to-face approach.

But the potential for a system like ePlans to help meliorate the problems at DPP is obvious. For example, Enomoto points out, it would allow the different agencies to review projects simultaneously rather than sequentially. Right now, permit applicants have to submit three identical sets of plans: site plans, which will stay at the building location; a tax set, which goes to the Tax Office for their records; and the building file set, which will ultimately remain with DPP. The problem, he says, is that, even though you have three sets of plans, all the agencies want to see the building file set, because it becomes the official plans.

“That means you’ve still got to run those plans by each department consecutively instead of concurrently. But, if everybody got to see an electronic copy, ePlans would allow them to look at it concurrently. It has a lot of features you can overlay, so you can see all the different changes.”

So, instead of fighting the ePlans system, Enomoto says, the staff at Palekana is trying to learn it. “I think we have about 80 plans in there now and they’re beginning to come out a lot faster. It’s a work in progress, but it seems like it’s getting better.”

ANOTHER APPROACH

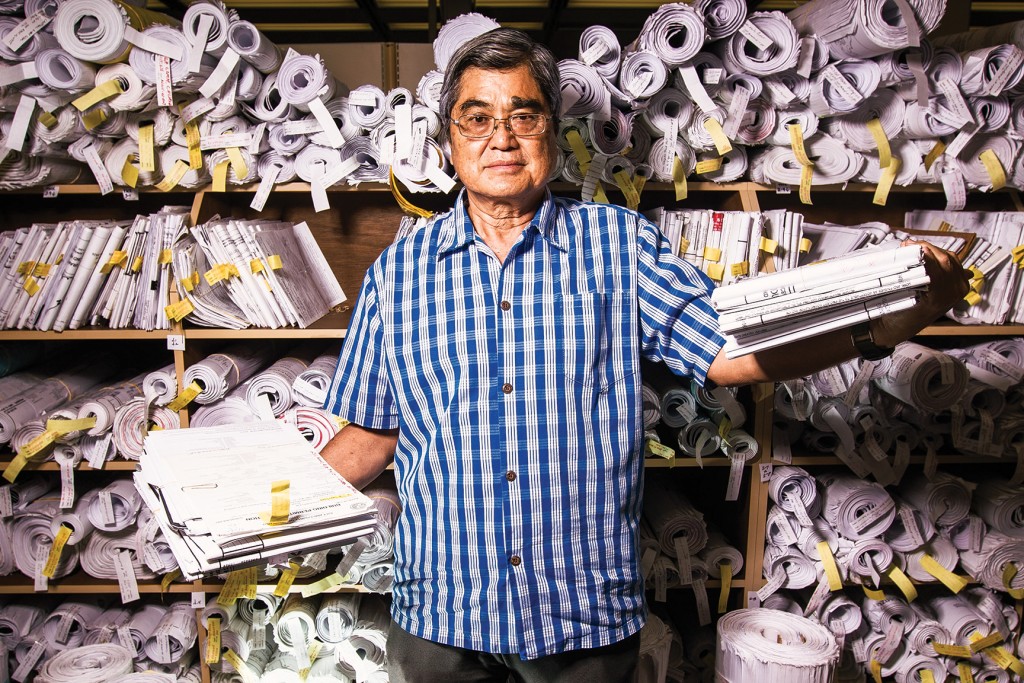

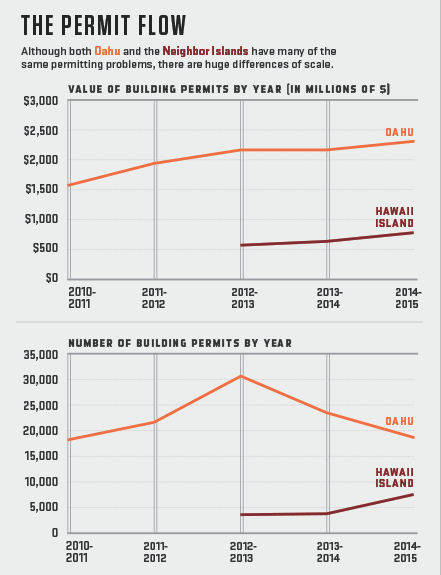

Honolulu isn’t the only county with complaints about its permitting system. Even though they don’t experience the volume of permit applications that Oahu does, the Neighbor Islands still face many of the same problems. Like Honolulu, they’re scrounging for answers. In some instances, they adopt Honolulu’s approach. For example, Hawaii County has implemented a one-time review system similar to Honolulu’s. But the Neighbor Islands are also cognizant of the differences between them and Oahu. Duane Kanuha, planning director for Hawaii County, describes the impetus and direction of some recent changes to that county’s permitting process.

“As an administration, we’ve been looking at how to improve the system for maybe a year already. Billy Kenoi, the mayor, basically said, ‘I had three platforms when I was elected two terms ago. One of them was to improve the mass transit system. I believe we’ve done that,’ he said. ‘Another one was to provide more parks and complete more roadway projects, and we’ve done that,’ he said. ‘The third one was to improve the building and permitting process. And,’ he said, ‘I still get people grabbing me in the airport and at functions and venting at me in terms of how long it’s been taking for what they consider a simple thing.’ So, he had team members in the administration basically put their heads together to fix it.”

Because planning directors throughout the state meet regularly to discuss common issues, Kanuha was familiar with what was happening at DPP in Honolulu.

“They’ve basically mushed everybody under Planning – all the line agencies: Permitting, what we call over here the Department of Environmental Management, sewers and all that stuff. All that got mushed under planning. So, when the mayor gave us this charge, I’m sitting there going, ‘Ah, shoot! He’s going to want to do the same thing they did in Honolulu. And, sure enough.”

Kanuha’s concern was well-founded, of course, but he also knew that Hawaii County isn’t the same as the City and County of Honolulu. “The thing is, they’ve been into their system for 10 or 12 years and George (Atta) would be the first to admit there are still lots of bugs in it. But those of us on the Neighbor Islands look at it and go, ‘Whatever the issues are, none of us have the flow of permitting that Honolulu has.’ ”

Even so, at first, he says, the Big Island’s plan looked similar to Honolulu’s. “Here in Hawaii County, the Hilo building that the Planning Department is in also has Parks and Recreation, Public Works, and Real Property Tax. So, one of the first things everybody looked at was: OK, either Planning moves across the hall to Public Works; or Public Works moves over to Planning. Then, we narrowed it down to: Maybe just the Building component of Public Works that moves over to Planning.”

In the end, though, both approaches seemed pointless. Both would be costly and it wasn’t clear that either department would have enough space to house the extra people. More important, moving people around could raise union issues and require Council approval. “By charter,” Kanuha says, “the function of Public Works is really separate from Planning. Public Works does Building and Permitting. Planning is just planning. So, to integrate those two, there was some talk that there may be a charter concern. And I think that’s what happened with the City and County of Honolulu – it had to redo the whole charter to make the move happen.”

If merging departments wasn’t the answer, how could they get the apparent efficiencies of a merger without actually moving people around?

“What we ended up doing,” Kanuha says, “was we kept both departments separate, but we reclassified our existing zoning clerks in the Planning Department to ‘land-use-plan checkers.’ That position series allows them to look at both our land-use zoning components as well as building components. So, it’s kind of like a merge of a zoning clerk and a building/permitting clerk. I think this is the same series that George (Atta) has in DPP. Then, we asked for three additional clerks, two in Hilo and one in Kona.”

These land-use-plan checkers, with their newly created authority, have become the linchpin of the permitting system for the county. All applications now route through them, Kanuha says.

“In other words, you don’t go to Public Works anymore for your application. Every application for any building permit has to come to the Planning Department first. The reason is, we were finding over time, that someone would walk down to Public Works Building Division, hand in a set of plans for a project, get logged into the system, and then get into the planning review room, and our staff shows up, looks at this project and says, ‘Hey, you know you need this other permit in order to do this? You actually shouldn’t be here.’ What happened was, in the planning review room, the project that hadn’t satisfied all of the land-use and zoning stuff gets kicked out. In the meantime, the applicant has put his project in and thinks he’s all good to go. He’s been in the system for maybe a couple of weeks, and then he gets bounced out and has to go back to Planning. So, you get this, ‘You told me to go here. He told me to go there.’

“One of our objectives is to make sure that whoever gets into the building permit process is all clear with the planning process first. Because sometimes there are things like special management area permits, or you need a variance or something, and it can take several months before you get it resolved. Some of the issues may require public hearings and all that stuff before you can even pull an application. So, the whole objective of shifting everything over here to Planning is that our land-use-plan checkers will be able to check all the plans to make sure all the information required for the building permit to actually get issued is also there.”

In addition to creating these land-use-plan checkers, Kanuha says, the county also held stakeholder meetings to see what specific improvements the industry wanted. “They said, ‘What would really help everybody out is some kind of an express lane.’ If I’ve got a PV system, and the policy is ‘first in/first out,’ and I’ve got a condo in front of me, I’ve got to wait until that condo gets processed before my PV system pops up.’ So, we said, ‘Okay, we’ll take that under advisement.’

“The other issue among the stakeholders was the back end, the inspection side – the long delay between when you call for an inspector and when one shows up. That was basically a manpower issue. Actually, when we were going through the process, I think Public Works said, ‘At any given time, we probably have five inspectors to cover the whole island.’ ”

This, of course, is a funding issue, like so many of the problems facing local government.

RESULTS

How are all these permitting improvements working? For the Big Island, it’s probably too early to tell, Kanuha says. “We only launched this on July 1, so we’ve only been at this for a few weeks now.” But this is Kanuha’s third time around in the government and he thinks he’s seen promising changes.

“Through my whole experience in government,” he says, “Public Works has always been Public Works and Planning has always been Planning. And a lot of times, people in Planning would say, ‘It’s not us; it’s over there in Public Works,’ or Public Works would go, ‘We don’t have that; go see Planning.’ That’s why you’ve got these people feeling like they’re being bounced back and forth, looking for whatever they’re supposed to do.”

Now, Kahuna says, even though the reorganization is new, he’s seeing more cooperation between Planning and Permitting. “What’s really interesting to me is the camaraderie between the Public Works people and my people in Planning. It’s really cool because people we would normally say, ‘It’s them,’ now, they’re over here and they’re saying, ‘This is how we do it over there. They’re on the counter with us folks, helping customers along – both in Hilo and in Kona. And we’re starting to see where we have backlogs in our implementation – which is the same kind of backlog they used to have over in Public Works – but, now that everything is coming here and they have some catch-up time over there, they’ll come over and say, ‘You know, we can help you with some of this.’

“We had an example in Kona a couple of weeks ago where I think there were like 90 online applications – primarily PV things – that, because my guys were dealing with everything coming in over the counter, checking for land use requirements on everything, they just weren’t able to get to everything. So, the Kona Public Works staff came up – they can see everything online – and they said, ‘Looks like there’s a backlog on the PV things.’ And my guys said, ‘Yeah, we just can’t get to it.’ And the Kona Public Works guys said, ‘You know what, why don’t you give it to us? We’ll take care of that.’ And they cleared off 90 applications in less than two days.”

But most of the improvements seem to be coming from the increased authority of the land-use-plan checkers. For example, Kanuha says, some of the clerks are also getting training from the electrical inspectors on what they should be looking for in terms of electrical permits.

“The standard complaint is that the review time takes too long. I would say that’s a valid complaint most of the time.”

— George Atta, Director, Honolulu Department of Planning and Permitting

“Nobody has ever looked at that before except the electrical guys. But we’ve noticed that there’s a backup on the electrical side, again, because of processing. Since electrical permits and plumbing permits are all coming here along with the building permit applications, some of our clerks are learning how do some preliminary calculations on the electrical permit side. That means, when the electrical guys over in Public Works get the stuff we’re through with, it’s kind of pre-checked, so they don’t get stuck having to start from zero.”

Something similar is also happening with other agencies, he adds. “The program we’re trying to get into is what we call an ‘opt-out’ program. In other words, if somebody comes in with an application that meets your department’s specs, do you really have to see it and sign off? So, we’ve reached an agreement with some agencies that basically says, ‘If the application has A, B and Z in it, I don’t have to look at it.’ So, they’re basically saying, ‘We’re opting out.’ ”

Finally, Kanuha says, the reorganization is improving the interaction between the department and the public. “My guys are out there encouraging the clerks, saying, ‘Customer service is everything. Even if there’s some waiting involved, or the answer they get is not what they expected, just give them the customer service.’ And what I’m starting to hear is that when the clerks are helping with somebody’s issues, the people who are waiting are looking at the people being serviced by our clerks and they’re going, ‘This is interesting. People are taking the time to explain what you need, where you can get it, or saying we’ll help you do this.’ So, when their turn comes up, it’s not like a doctor’s office.”

“I have not witnessed any favoritism at all, ever.”

— Heidi Levora, Co-owner, Anchor Systems Hawaii

So, things look promising for Hawaii Island, though it’s very early in the process. Even though there are few complaints at this point, it’s unclear whether the changes in the Hawaii County permitting process will speed things up. Back at the City and County of Honolulu Department of Planning and Permitting, things are less ambiguous.

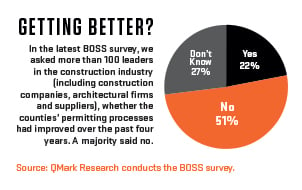

“So far, we’re not making much headway,” Atta says. “All the measures we’ve taken just have us treading water. When I ask our guys, ‘How come we’re not doing better?’ they say, ‘We’re processing more permits than ever before.’ And it’s true. With this construction boom, we’re processing more permits even though it’s not going any faster. But we would really like to shorten the time it takes to get a permit. By the end of the year, we’re hoping the average wait period is 10 percent faster than it was last year.”

For entrepreneurs like Hideo Simon, that may not be enough. He suggests changing the permit system so that, if your permit isn’t reviewed within a certain time, then it’s automatically approved. Similarly, if your inspector doesn’t show up by such and such a date, you pass. Mostly, though, Simon wants the city to play a more supportive role for local businesses.

“We’re trying to make a state that loves small businesses,” he says, “where it’s not about the permitting process. Personally, I love burgers and beer. I just want to put great burgers and beer in front of my customers. I don’t know what happened to my love of burgers, but now all my energy and effort are caught up in the process.”