A Diverse Economy

Does Hawaii need one? How should we get it?

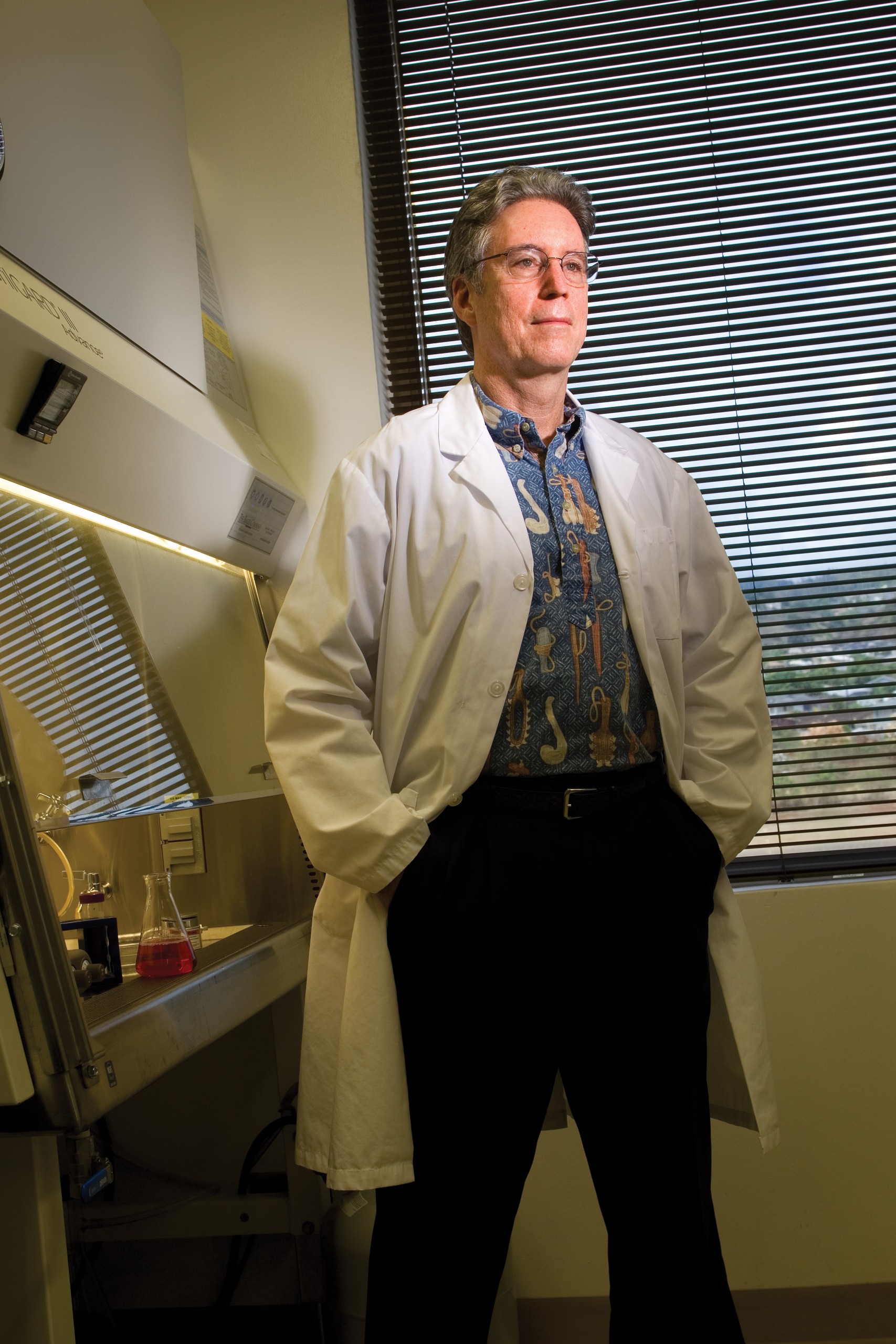

When it comes to diversifying Hawaii’s economy, Paul Brewbaker has his doubts. As a longtime member of the state Council on Revenues and the former chief economist at the Bank of Hawaii, Brewbaker’s seen all the hopeful visions of Hawaii as a technological hub – a center of biotechnology or alternative energy or digital media. He’s also heard the endless political debate on what exactly is the right mix of tax policy and government assistance to achieve this vision. None of it, though, fits the classical economic theory through which he views the world. That makes him a rare skeptic in a crowd of believers.

“In Hawaii,” Brewbaker says, “the diversification mantra is something that was handed down to policymakers from Moses along with the Ten Commandments.” Although there have certainly been differences of opinion on how to achieve it, this long-standing faith in diversification is manifest in an alphabet soup of government agencies, programs, nonprofit organizations, public/private partnerships and legislative acts – HTDV, CEROS, HTDC, HTIC, SPIF, HCDC, Act 152, Act 110, Act 221/215, etc. – each of them created, in large measure, to help diversify Hawaii’s economy. “Every politician believes, ‘Thou shalt diversify Hawaii’s economy,’ ” Brewbaker says, “because, by now, everyone expects it.” The question, of course, is why?

The simple answer is money. Underlying most arguments for diversification is the premise that new industries will bring more money into the state in the form of better, higher-paying jobs. Within the tech sector (and most of those arguing for diversification are talking about technology), there’s mounting evidence that it’s already happening.

Last year, the Hawaii Science and Technology Council, a tech-industry trade association, collaborated with the Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism to produce the first detailed report profiling the “Innovation and Technology Sector” in Hawaii. Perhaps the most impressive finding is the size of the sector today. According to the report, in 2007, combined public and private tech-sector employment totaled 31,106 workers, nearly a 3 percent increase from 2002. Perhaps more important, the average annual earnings for tech workers was $68,935 — 57 percent higher than the state average of $43,963. Collectively, the sector contributed $3 billion, or 5 percent, of the state’s $61 billion economy. Put another way, the tech sector had the same impact on the gross state product as the accommodations industry.

For many members of the tech sector, these numbers are justification for government efforts at diversification, like the controversial Act 221 tax credits. According to Lisa Gibson, HiSciTech’s executive director, it’s also evidence of the importance of nurturing the budding tech sector. “If you have a company and you have a product,” she says, “you track the performance of your product. You do market research. You look at your organization’s strengths; you look at its weaknesses. It’s completely analogous to diversifying your economy. The sectors are your line of products. We’ve got existing products like tourism, construction and ag. We need to develop new ones, like biotechnology, digital media and dual use.” These are the jobs of the future.

“In classic portfolio theory, one seeks diversification as a way of maximizing risk-adjusted returns,” Brewbaker says, but government usually approaches economic diversification blindly.

But diversification is not just about jobs. It’s also about creating sustainable tax revenues. “It’s important to say that any revenue generation plan for the state has to be multifaceted,” Gibson says. “It’s no different from your own stock portfolio.” That’s a common view in the tech community.

Bill Spencer, CEO of Hawaii Oceanic Technology and president of the Hawaii Venture Capital Association, notes, “Right now, we have an economy that depends on tourism to survive. Yet, here we are – we don’t even have enough revenue to keep our beach bathrooms clean.” Like Gibson, Spencer believes the solution lies in building a broader base for the economy. “We’re missing one leg of the stool. We need a third leg, some way to balance the economy – because right now, if anything hurts tourism, tourism goes down and we’re in the dump.”

Economist

Paul Brewbaker is skeptical of government attempts to diversify Hawaii’s economy. | Photo: Rae Huo

But to Brewbaker, diversification isn’t about jobs – or even revenues, exactly – though he does agree with the analogy of the economy as an investment portfolio. “In classic portfolio theory,” he says, “one seeks diversification as a way of maximizing risk-adjusted returns.” The idea is to reduce risk by carrying a mix of assets. That way, when one class of investments is depressed (stocks and bonds for the individual investor, say, or tourism and construction for the larger economy), the effect is moderated by others in your portfolio (real estate and commodities for the individual, or high tech and film for the state). Economists call this effect “negative cross-correlation.” The problem, according to Brewbaker, is that the government usually approaches economic diversification blindly.

“Nobody,” he says, “actually does any analysis as to whether, by diversifying into a particular industry, the negative cross-correlation of its performance with respect to existing industries’ performances is risk-reducing. The state doesn’t even know what that last sentence means; and yet, it is the actual reason for diversifying a portfolio!”

A Capital Idea

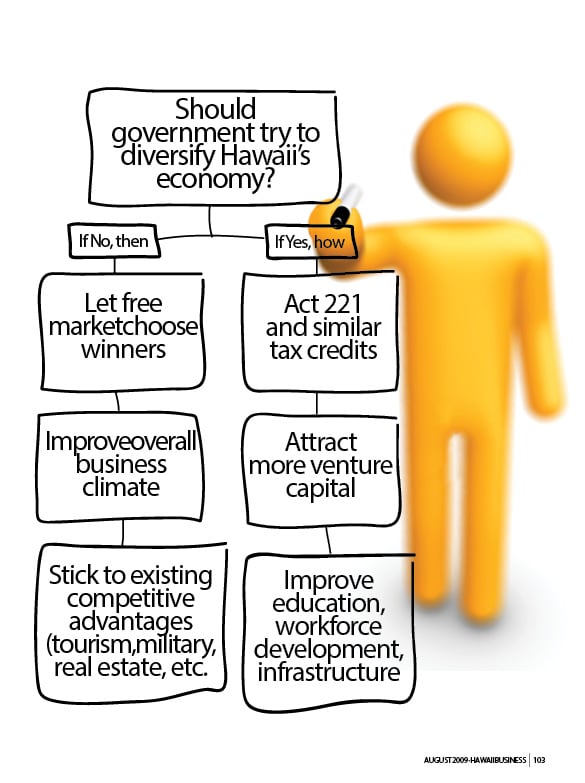

Still, the march toward diversification stumbles on. Broadly speaking, there are two camps in the debate on how to get there. (True skeptics, like Brewbaker, rarely get to make their case.) One camp believes that the main impediment to growing a vibrant tech sector is a shortage of investment capital for promising companies. The other camp, while acknowledging the dearth of capital, believes that the cure is much more complicated and includes better education, workforce development and improved infrastructure. Their debates resemble the old “chicken or the egg” dilemma.

David Watumull, president and CEO of Cardax Pharmaceuticals, believes the problem is capital. He points out that Hawaii is fairly efficient at supporting early-stage companies, helping them with proof of concept. Angel investors and a series of tax credits play a vital role at this level. “(Act) 221 was certainly part of that,” Watumull says. “It did an excellent job of getting startups going.” The difficulty, he points out, is funding the growth stages that produce viable, profitable companies. “That’s traditionally been funded by venture capital,” he says, “and Hawaii’s traditionally venture poor.”

This gap creates a kind of valley of death for Hawaii tech firms. Some stagnate and fail. Others find funding elsewhere and have to move. Watumull intones a short list of Hawaii success stories that left the Islands: Verifone, Digital Island, Pihana. He points out, “Each one probably raised a couple of million dollars and went from 10, 20, 30 people, to hundreds, maybe thousands of employees. If we want that type of growth here in Hawaii – which I believe we do – then we have to find a way to attract capital.”

David Watumull, CEO of Cardax Pharmaceuticals, says Hawaii’s lack of venture capital prevents local start-ups from growing or forces them to move. | Photo: Rae Huo

To illustrate the primacy of capital in the diversification equation, Watumull likes to contrast three cities that have worked hard to create biosciences sectors: San Francisco, San Diego and Baltimore. While the first two cities have been successful, Baltimore’s efforts have been anemic, despite several advantages. Watumull notes, “They have an excellent research institution, Johns Hopkins University; they’re right near D.C.; and they have the largest number of NIH grants. But they still have very little biotech – nowhere near Boston or San Francisco or San Diego.” The reason, he says, is that those cities have capital.

Some of that, Watumull believes, is simply chance. “Each of those places started with just one or two successes,” he says, “people who by hook or by crook got their company to where they could sell it.” These successes, however accidental, provided the capital for further growth in the region. But, while that model could work here in Hawaii, it’s not a good bet. As Watumull puts it, “Here we are in the middle of the ocean, geographically isolated. We’re going to have to be proactive.” He gives several examples of regions with successful diversification strategies: Singapore, which invested its enormous sovereign funds to essentially buy a biotech industry; Arizona, which has used a carefully calibrated set of tax breaks and grants to encourage investment; and especially, Utah, which, with the bold use of a tool called a fund of funds, has managed to both create a homegrown tech industry and lure several major corporations to the state. (See sidebar on page 110.) “There are definitely ways that we could attract some significant amounts of capital,” Watumull says, “enough to have a substantial impact on Hawaii.”

All of these strategies rely on tax credits and similar tools. But Brewbaker remains skeptical about the use of tax credits, particular one-to-one credits like Act 221. “If you’re a high net-worth individual with millions of dollars in income and a $100,000 tax liability with the state, you can simply invest in a qualifying high-technology business (the definition of which is arbitrary, if loosely sensible) and claim a tax credit for the entire amount. In effect, the state has given you back the $100,000 you owed.”

According to Brewbaker, this sort of tax credit can only distort the behavior of investors. He emphasizes this with a parable: “Suppose you and I wanted to set up a company with Bernie Madoff that guaranteed investors would never have to pay state income taxes for as long as they lived, and might, in the process, actually get a return on their investment. We could loot them for millions of dollars and spend it on ourselves. The investors would probably get nothing in return, but they would still be no worse off than if they had given the same amount of money to the state.”

Of course, the whole idea of these kinds of tax credits is to change the equation of risk and reward for the investor. Sometimes, the credit is designed to make some desirable kind of investment (clean energy, low-income housing) pencil out, offsetting some of the cost for the investor. Some credits, like 221, effectively shift the risk from the investor to the state. Brewbaker’s point is that investors need a true metric of risk and reward — economists call it risk-adjusted returns — in order to act efficiently. “Act 221 isn’t just inefficient; it’s outright pernicious,” he says.

Enterprise Honolulu’s leaders are, from left, Managing Director Mark McGuffie, Executive Director Pono Shim and past Executive Director Mike Fitzgerald. | Photo: Rae Huo

Some See a Broader Problem

Ted Liu, director of the Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism, is one of those who don’t think capital alone will work. Where Watumull says, “Capital comes first, then, the other pieces of it (education, workforce development, infrastructure) will come along later,” Liu believes those other pieces are a big reason there’s no capital in the first place. “I don’t think it’s capital driven,” he says. “Capital will go to places where it can be used.” The key to diversification, according to people in this camp, is not tax credits for wealthy investors, but an emphasis on things like science, technology, engineering and math education programs; worker training; infrastructure, like wet labs and incubators; and even lifestyle issues such as the arts and cultural festivals. Liu poses the question: “Why isn’t the private sector providing the capital now?” The answer, he says, is that “there are better opportunities elsewhere. If we want them to invest here, we have to make those opportunities better here.”

This broader view of diversification has currency in surprising places. Among the leadership of Enterprise Honolulu, for example, there seems to be a general agreement that the process will have to be more comprehensive than simply replacing Act 221 or creating a fund of funds. Board member Mark Ritchie likes to use the example of Ireland, a country that, within a generation, went from last in per capita income in the European Union to first. But the so-called Irish Miracle required an extraordinary level of conversation and consensus within the country. There’s the rub.

Pono Shim, the kahu and new president of Enterprise Honolulu, says this is the challenge facing Hawaii today. “Can we have a simple, open, honest conversation about who we are, where we are and where are we going? Until that happens, there will be no economic development that’s going to span Hawaii’s future.”

Outgoing Enterprise Honolulu president Mike Fitzgerald agrees. “Until and unless a new community discussion can take place here among the stakeholders – not just business, not just government, not just unions, not just environmentalists, not just the university, but bring those forces together and have citizens have a stake – this place has marooned itself.”

But Fitzgerald remains stubbornly optimistic. “Just think of these challenges facing Hawaii right now: First, I would argue that it’s the most vulnerable place on the planet because of imported oil and imported fuel.” Hawaii, he says, is also disproportionately impacted by any hiccup in the world economy. “All that said – and those are all challenges – Hawaii has a better set of real assets to deal with these than almost anywhere on the planet: every renewable energy asset, 365 days of growing capacity, clean, blue water for ocean research.” Just solving our own problems, in other words, will create a clean, sustainable, diversified economy.

Of course, according to Brewbaker, this all misses the point. Like most economists, he believes diversification is the wrong goal. According to the theory of comparative advantage, specialization is the better plan for a small, open economy like Hawaii. “The idea,” Brewbaker says, “is that, through production specialization in an economy’s comparative advantage, welfare will be maximized.” It’s best, he says, to simply trade what you do well for all the cheaper stuff we can import from others. Economically speaking, if Hawaii can’t attract venture capital or produce an educated workforce or a modern infrastructure, maybe technology isn’t our proper specialization.

“Tourism seems like the obvious choice to me,” Brewbaker says.

Utah’s Model

The state of Utah has taken a bold approach to the capital problem. Using $300 million in refundable tax credits as a guarantee, Utah has attracted more than $100 million in private investment for a state-run fund of funds. Of course, like any large institutional investor, the fund of funds doesn’t invest directly in companies; it invests in venture funds that, in turn, invest in their own portfolios of firms. That much, at least, is classic venture capitalism. The risky part is there’s no guarantee that any of this money will ever come back to the state. To take advantage of the tax credits, all that’s required is that these venture funds “commit to having a working relationship with the Utah Fund of Funds.”

According to Jason Perry, director of the Governor’s Office of Economic Development, it’s the state’s job to convince those venture capitalists to invest the money back into Utah. He points out they have a wide range of incentives. “We have tax credits to expand or relocate. And we offer up to 30 percent credits for sales, income and withholding taxes for up to 20 years.”

It seems to work. Jeremy Neilson, who manages the fund of funds, points out that only $45 million of the fund has been expended so far, “but we’ve had over $165 million invested in Utah companies.” And that’s only counting investments from out-of-state venture funds. “If you count all the money invested,” Neilson says, “there’s a total of $615 million dollars syndicated.” That’s a 12-fold return on investment.

The best part is Utah isn’t out a dime of upfront money. The refundable tax credits that guarantee the fund of funds only come due in 10 years, and only if the investments lose money. Regarding the incentives for companies to come to Utah, Perry points out, “It’s all post-performance. We never give up a penny of state money until we have a dollar in our pocket.”