Sun Noodle’s Ever Expanding Universe

It’s as if the noodles from Sun Noodle have a life of their own.

In 1982, the first batch emerged from a Kalihi warehouse. Three decades later, Sun Noodle makes enough noodles each week to circle the world at the equator. First, the noodles stretched from Hawaii across the Pacific to Los Angeles, unspooled from there to New York and now are crossing another ocean to entice Europe. Soon, there may be a day when the sun never sets on Sun Noodle.

Here in Hawaii, its noodles are everywhere, even where you’d least expect them: It makes the saimin in your S&S Saimin cup, the ramen at Yotteko-Ya restaurant on Kapiolani Boulevard and, even, the fresh pasta at Taormina Sicilian Cuisine in Waikiki.

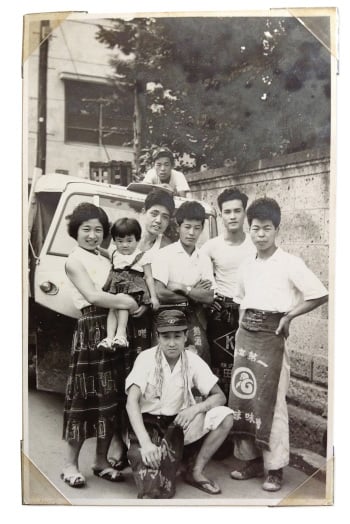

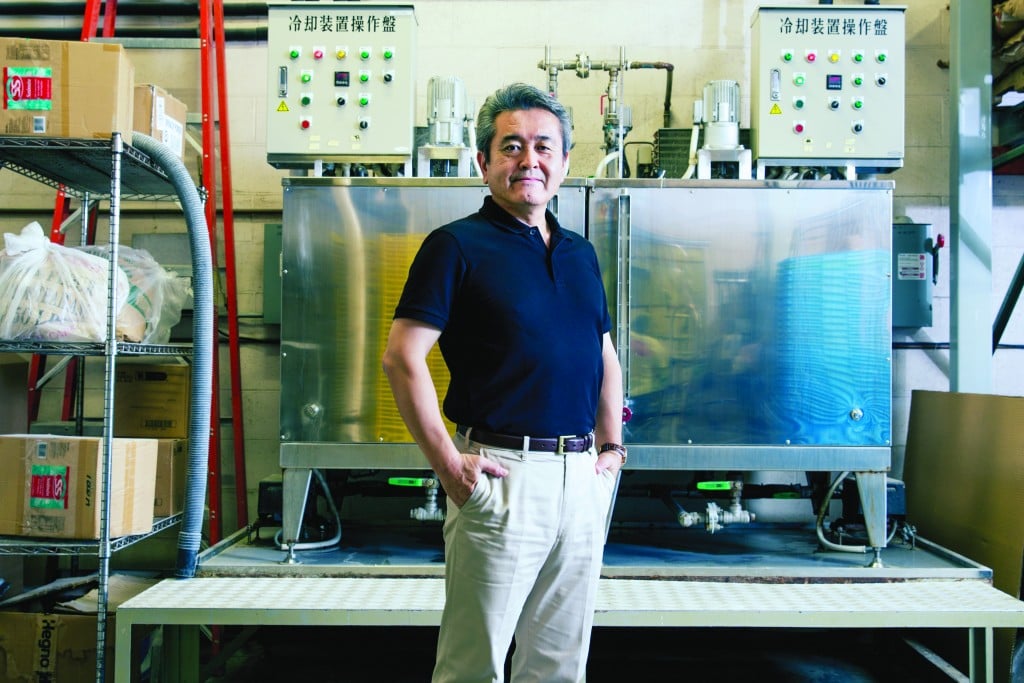

It all started when a 20-year-old from Japan came to Hawaii to see about a noodle machine. Hidehito Uki’s father, a noodle maker in Togichi, Japan, had been working on a project in Honolulu, but it fell through, leaving behind a noodle machine that was Uki’s if he wanted it. He did – or, rather, he really wanted to be in Hawaii. Because if he had done his research (which he hadn’t), he would have discovered that Honolulu had just three ramen restaurants and 20 other noodle factories, making mostly Chinese noodles and saimin.

Today, there are 56 ramen shops, but, in the beginning of Sun Noodle, no one here really knew ramen. Uki couldn’t even get the right flour at first. In Japan, there are hundreds of varieties of flour milled specifically for ramen. What Uki needed was a flour with a high protein content for firmness, that was also bright white, unlike saimin noodles, which are grayish. He went to Hawaiian Flour Mills and, luckily, the owner spoke Japanese and agreed to make a special flour for him.

Ramen noodles finally in hand, Uki knocked on the doors of restaurants and presented his product, in limited English. The restaurants rejected him, complaining the noodles were too hard.

“I tried to explain texture, that you have to have this in the noodles. They didn’t understand,” says Uki.

It took him about 15 noodle iterations before he landed one of his first customers, Ezogiku restaurant, then on Kuhio Avenue in Waikiki. Thirty years later, Ezogiku, now with five locations, still uses Sun Noodle, as do all the ramen restaurants in Honolulu, except for one. Sun Noodle’s factories serving Los Angeles and New York City produce primarily ramen; its market shares in those areas’ ramen-centric restaurants are 70 percent. In fact, nine of the top 10 ramen shops in New York City, as listed by The New York Times in March, serve Sun Noodle.

How did a small Kalihi factory end up being America’s dominant force in ramen? It took two generations of foresight: first from Uki and, 20 years later, from his son, Kenshiro.

Custom Noodles

Ramen noodles are generally made of just four ingredients: flour, water, salt and kansui. Kansui, a mixture of sodium and potassium carbonate, gives ramen its distinctive flavor, aroma, color and firmness. But the possibilities in texture, thickness and flavor appear to be endless. Sun Noodle currently makes about 190 different types of noodles, customized for its customers.

“The great thing about those guys, the reason they’re doing so well, is their customer service is unparalleled,” says Ivan Orkin, a native New Yorker who became one of Japan’s most famous ramen chefs and recently opened two new restaurants in New York. “They try really hard. They never say no. They always try to figure out a way to satisfy their customers.”

Uki hatched this business model – of noodles tailored to each restaurant – about seven years into the creation of Sun Noodle. It was a confluence of events that spurred Uki to step up his game, to become more than a small-time noodle maker. First, his father’s business in Japan went bankrupt. He felt no longer able to rely on his family for support. “So, after that time, I really work hard to get more accounts, get more business, increase the revenue and that was one turning point that changed my mentality,” says Uki, with his Japanese accent still strong after 33 years living in Hawaii. “I have to be more serious in business, so I studied accounting, too.”

Around that time, Ito En, the Japanese beverage giant, acquired S&S Saimin. “As soon as I heard that, I think Ito En probably not only focusing on beverage business, but also noodles,” he says. “I feel I have to do something about that. I have small family business and financially I am not strong enough, so if they come to the market and we compete, I know we are going to fail and lose. So what we can do to fight with a big company? An idea came up to work with individual restaurants. So we can make a strong relationship with individuals. We provide a noodle match with the soup. Even if [a restaurant] make very good soup, even if we make a very good noodle, if it doesn’t match, it doesn’t taste good.”

Ito En did enter the fresh noodle market and, for almost 20 years, the two competed on shelves and in bowls. But, by 2006, Ito En ceded to Sun Noodle, closing its noodle operations and selling S&S Saimin to its rival.

Moving East

In 2004, Uki decided to open a Los Angeles factory. He had already been shipping noodles to Los Angeles restaurants from Honolulu – building a factory was a natural step because no one else was doing what Sun Noodle does.

“I talked to ramen shop owners and found out there was no choice,” Uki says. “If they wanted to open a ramen shop, a distributor come with sample. You can choose from only limited amount. None of the noodle company work with ramen shop to create their own noodles. Not only that, my price of noodles in Hawaii is, say, 35 cents a portion and in Los Angeles, [other companies are selling for] about 60 cents.”

Uki was confident he had the competition beaten. He bought his noodle-making machines and built his Los Angeles factory – only to discover that no distributors would carry his noodles.

They all had allegiances to other ramen makers. So Uki went back to what he knew from growing his business in Hawaii: “We visit every ramen shop, told them, ‘We want to make custom noodle only for you.’ … I went to the end user first. The end user command to the distributor to bring my noodle.” Today, all three of the main Japanese food distributors in the United States – JFC International, Nishimoto Trading Co. and Mutual Trading – carry Sun Noodle noodles.

Business increased so much that, by 2009, Sun Noodle expanded into a larger space in Los Angeles. Uki says, “What I most like about the property? The name of the street: West Mahalo Place.”

Son of Sun Noodle

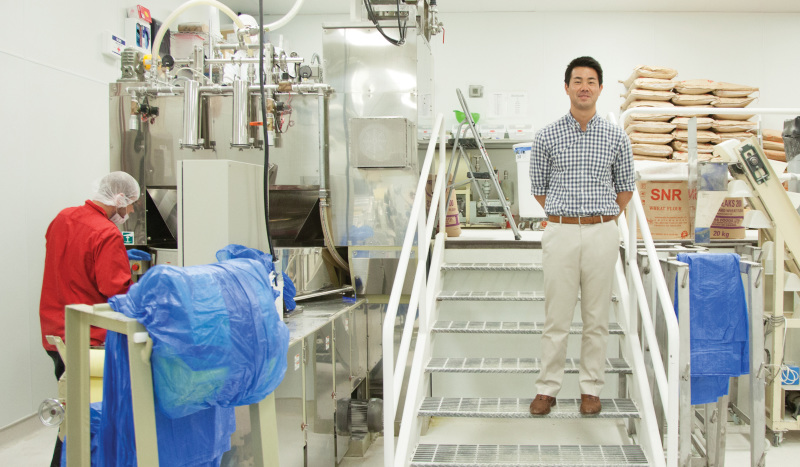

“I came to the conclusion that our products sucked,” says Kenshiro, on why he founded the New Jersey factory. He had graduated from Whitworth University in Washington in 2008 and went straight to work at Sun Noodle’s Los Angeles factory. Kenshiro had been involved on the periphery of the family business since he was 10: first, packing noodles, then delivering them when he got his driver’s license. While studying international business in college, he tested some things he had learned when he came home during the summer.

Opposite page, top: Kenshiro Uki, a third-generation noodle maker, set up this Sun Noodle factory in New Jersey last year. Today, it supplies 70 percent of New York City’s ramen restaurants. Photo: Harold Julian

“I tried to implement a policy so that drivers would take more pride in their vehicles,” he says. “It was some kind of clean-your-vehicle schedule. It failed because I was a 19-year-old kid trying to do something to these people who had been working for the company since I was born.”

Three years later, he wasn’t just trying to improve corporate culture, he was running the L.A. factory with only three other employees, supplying many of California’s ramen shops, plus more around the country. Until then, though, Kenshiro was looking at Sun Noodle mostly as a business and operations challenge. It wasn’t until he met ramen chef Shigetoshi Nakamura that he really started appreciating the noodle. Nakamura “is a legendary ramen guy,” says Orkin. “He was one of the first, most important ramen people in Japan.”

“Nakamura [was coming to L.A.] to consult on a ramen shop,” Kenshiro says. “When you hear this guy is coming, you do everything you can to impress him. I spent the whole night [before his visit], shining everything, cleaning everything, the equipment and then just waiting for him the next day in the factory. He didn’t come to the factory. He just met with my general manager and was in and out in 30 minutes.”

“If I want to meet someone, I’ll make it important and aggressively try to meet him,” Kenshiro says of Nakamura. “When he opened the shop Ramen California, I would go there every day after work to eat his ramen. When he wasn’t busy, I would approach him. It was very difficult. He’s a [famous] guy, I’m just a little kid. But he started putting up with me and talking.”

In 2011, the two flew to New York. They ate ramen at some of the restaurants serving Sun Noodle, and that’s when Kenshiro discovered “our noodles were poor. They weren’t represented well.” Sun Noodle was shipping its noodles frozen to New York, which made them as fragile as glass. They would arrive at the restaurants broken or partially thawed and refrozen, about as appealing as ice cream with serious freezer burn. Before boarding a flight back to L.A., Kenshiro emailed his father, saying they needed to open a New York-area factory. By the time he landed, Uki had left him a voicemail: “OK, get ready to move.”

Two months later, Kenshiro was building a factory in Teterboro, N.J., and driving up and down the East Coast, meeting with the owners and chefs of ramen restaurants to learn their needs. “One thing we knew was that, to become a leader, we had to be here (in the New York City area), because that’s where the chefs are,” says Kenshiro. “That way, we can really communicate one on one to see what they are really trying to do and be inspired by that and try to create a noodle. There are some customers who have a different idea on how to make ramen. But you just accept it and try to make a noodle that fits what they’re trying to express to their customers.”

Sales and Spotlights

When Kenshiro first started hitting the pavement in New York, he was 22, not long out of college. He was building a factory, which he’d never done before, and Sun Noodle on the East Coast was “getting our butts kicked by the competition,” Kenshiro says.

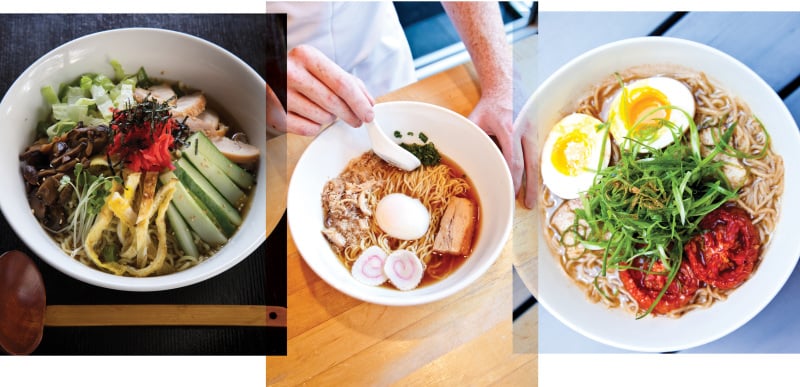

Sun Noodle creates custom noodles for its clients in Hawaii, Los Angeles and New York City. Here are ramen dishes from just three of the restaurants supplied by Sun. From left: Menchanko Tei on Keeaumoku Street in Honolulu, a Momofuku restaurant in New York City, and Ivan Ramen in New York City. Photo on left: Olivier Koning. Center and right, Harold Julian

What did he do? Same as what his dad did in Hawaii and Los Angeles. “Every day, I would go and meet customers. My biggest asset was, I knew how to talk about noodles, about ingredients. People were buying from our competition and my only way to show them that I knew what I was talking about was to take one of their noodles and do my best with a similar or better noodle. Or one to match the soup better. I’d have my L.A. manager FedEx me fresh noodles, cut a certain way, a certain weight. And once I got it FedExed to my apartment, I’d take it right away to the ramen shop and let them try it. I think doing it just the way my father did it – going back and forth, showing them that we really care – gave us our first in.”

Being near the chefs also meant being in the media spotlight, something Kenshiro hadn’t anticipated. “Guys like David Chang (from Momofuku), he was already buying from us. If you could tell people you’re with Momofuku, that’s a huge thing for non-Japanese. But the chef that really triggered our brand presence here (in New York), before we started getting market share, was Marcus Samuelsson.”

Samuelsson is a James Beard-award winning chef known for his restaurants Aquavit and the Red Rooster, and also a winner on the TV show Top Chef Masters. He took a tour of Sun Noodle’s New Jersey factory and Kenshiro created a noodle to represent Samuelsson’s background – Ethiopian-born and Swedish-raised – by making ramen with teff, a grain that’s used in the staple Ethiopian bread, injera. The media caught on and “It spread like wildfire. We were getting calls from ABC, NBC, newspapers and everything. And it just started getting bigger and bigger.”

Two years ago, Sun Noodle was at 20 percent market share among New York City ramen restaurants; it’s at 70 percent now.

Future of Ramen

When you already dominate the market, what do you do next? You grow the market. “We can’t just sell noodles when people don’t know a lot about ramen,” says Kenshiro. “So we sell basic building blocks for people starting ramen shops. Not every ramen shop can make everything from scratch.” He and Nakamura are developing the other components of a bowl of ramen – soups, tare (a liquid seasoning) and aroma oils – to sell as a package. And just as with Coca Cola’s formula, a different company manufactures each element so Sun Noodle’s recipes remain secret.

“We give the chefs the tools and pieces of what makes a great ramen so they can build on that,” says Kenshiro. Some of those pieces are what will actually go in the bowl, but the other tool is noodle education, both for chefs and for eaters. Kenshiro and Nakamura are building a 400-square-foot ramen restaurant in Manhattan, called Ramen Lab. There, they’ll serve flights of ramen to teach the history of the noodles and how the noodles play against the soup.

“If no one else is trying to showcase what ramen is, people are always going to have the image of instant ramen,” Kenshiro says. He wants to move the noodles into the craft realm, which doesn’t just mean clones of Japanese ramen styles, but bowls of uniquely American ramen. Like pizza or barbecue, someday, he hopes he’ll be able to travel to New York, San Francisco or Atlanta and taste each city’s style of ramen. He says, “The end goal is to create a culture where ramen is very regional and very local.” Local ramen, global Sun Noodle.