The Billion Dollar Gamble

What a difference a billion dollars makes.

Until recently, the state treasury – officially, the Treasury Management Branch of the Financial Administration Division of the Department of Budget and Finance – has operated in relative obscurity. With its staff of seven or eight employees, the treasury acts as cash manager for the state government. Its primary responsibility is to make sure the state always has enough cash reserves to meet its ongoing obligations: payroll, debt service, pension contributions, etc.

The treasury also manages the day-to-day investment of so-called excess funds: monies collected, but not yet spent, by state agencies. As it happens, that’s a lot of money – more than $3 billion at last count. Even so, these investments are hardly sexy, consisting mostly of safe, low-yield, highly liquid instruments like U.S Treasury securities, Federal Agency securities, collateralized CDs and something called SLARS, student loan auction rate securities. In other words: boring, boring, boring.

Then, in February 2008, the market for those auction rate securities collapsed. Overnight, the state’s $1 billion investment in SLARS ceased to be either safe or liquid. And suddenly, the treasury didn’t seem so boring after all.

Where the money goes

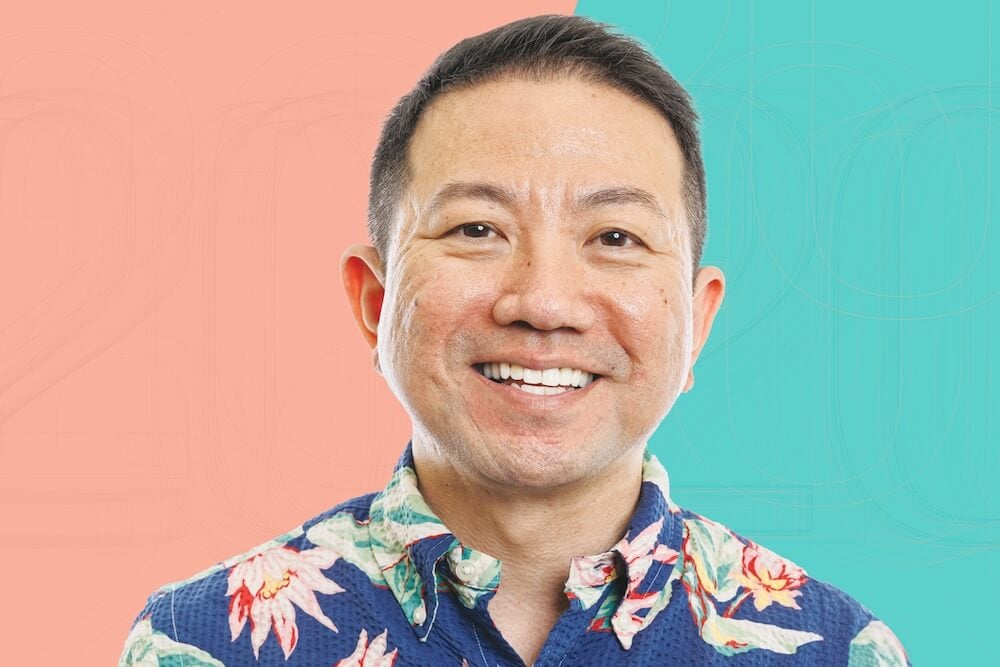

So, where did it go wrong? Georgina Kawamura, director of the Department of Budget and Finance, and the official state treasurer, describes treasury operations as a juggling act. “Here’s the day,” she says. “We get daily reports from the banks to let us know our ‘checking account’ balance. We also know, on a daily basis, what investments will mature.” These figures, combined with information about payments that will go out, constitute the calculus of the day’s excess funds, the funds available for investment. This begins yet another juggling act.

For the most part, treasury investments are scheduled to mature around large payments. Scott Kami, administrator of the Financial Administration Division (FAD), which oversees day-to-day operations of the treasury, gives the example of payday. Payroll, he says, averages about $8 million per pay period. “Normally, we schedule about half of that to mature on Friday, and the other half to mature on the following Monday. Because, historically, that’s how the checks clear.”

Armed with that information, treasury accountants can now contact brokers, banks and other financial institutions to find investment opportunities. In this way, the treasury’s responsibilities of cash management and investing are always intertwined. Every debt obligation and every dollar of excess cash must be meticulously tracked because, as Kawamura points out, “All the money is invested. All of it is earning interest.”

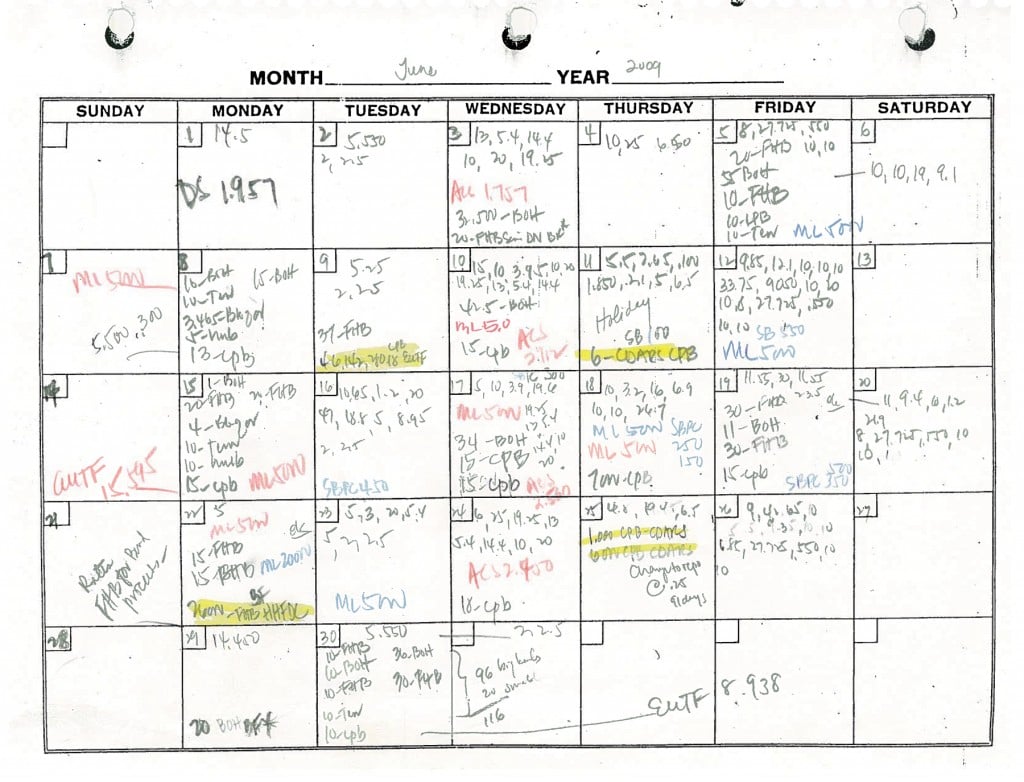

And yet, in a scathing report on the Department of Budget and Finance released in March, state auditor Marion Higa turns most of these mundane details on their head. For example, the treasury uses an almost indecipherable, handwritten, color-coded monthly calendar to monitor its investments. It calculates excess cash from manually prepared worksheets rather than electronic spreadsheets like Excel. And it deals with brokers through a decidedly informal system of e-mail and faxes.

Still worse, Higa says, is the treasury’s lack of oversight. The report notes that the FAD failed to prepare and review bank reconciliations, failed to produce a monthly investment report, and routinely allowed investment classes to exceed their statutory limits. In her view, it was this lax supervision that allowed the SLARS calamity. When the independent accounting firm Accuity conducted the state’s fiscal year 2008 certified annual financial report, it also said flawed internal controls led to the SLARS purchase. In her report, Higa points out that treasury staff never even saw the offering documents for these investments. Those documents clearly state many of the risks pertaining to SLARS.

What Are SLARS?

Auction rate securities are basically debt instruments consisting of bundles of securities – in this case, student loans. The interest rates are set through periodic auctions: sellers offer securities at the lowest rate they’re willing to accept; buyers indicate the highest rate they’re willing to pay and how many they want to buy at that rate. This process is designed to determine the lowest interest rate at which all available shares of a security can be sold at par. This is called the clearing rate, and it serves as the interest rate for that entire issue of SLARS until the next auction. In the event an auction fails, the rate is set based on a pre-established relationship to some benchmark, usually the London Interbank Offered Rate, or LIBOR. Naturally, brokers assure buyers that auctions never fail.

To be fair, these auctions appeared to work efficiently for more than 20 years. And because the auctions usually happened every seven, 28 or 35 days, investors like the state treasury could treat SLARS as liquid investments, even though the underlying securities might not mature for 35 years. But sustaining that liquidity meant that all the available SLARS had to sell at every auction. That didn’t always happen, but the underwriting broker quietly bought enough to keep the auction from failing. Between auctions, brokers often tried to unload these securities on their customers.

Nevertheless, in 2007, when the financial markets began to implode, these securities began to accumulate on the wire-houses’ books, and brokers regarded them nervously. They encouraged their sales divisions to push ARS aggressively, even though insiders knew the auctions were becoming tenuous. Another sign of some distress in the market was the steady increase in interest rates, which, in the case of SLARS, eventually reached 7.35 percent (compared with 2.07 percent for two-year CDs.) For most investors, higher interest rates reflect higher risk. And yet, in the six months leading up to the market failure, the Hawaii treasury’s holdings in SLARS went from $427 million to over $1 billion, and from just 14 percent of the state’s portfolio to nearly 30 percent.

Of course, the state of Hawaii wasn’t the only investor surprised by the failure of the ARS market. Thousands of individuals and hundreds of institutional investors were caught off guard. A diverse group of government entities – states, counties, water-district boards, et al. – now found themselves stuck with these now long-term investments. Although most individual investors eventually recouped their investments through settlements with the wire houses that underwrote the auctions and government regulators, institutional investors have been obliged to write down their ARS as part of the “mark to market” standards of generally accepted accounting practices. In the summer of 2008, for example, the state acknowledged a $114 million impairment on its certified annual financial report as a result of its SLARS holdings. Though Hawaii may have the largest holdings, it hasn’t taken the worst blow. Jefferson County, Ala., is verging on bankruptcy due to the failure of the auctions.

Closer to home, Maui County found itself stuck with more than $30 million in SLARS when the market crashed. Like the state, Maui seems to have relied on assurances by a broker, in this case, Merrill Lynch, that these were highly liquid securities. Also like the state, Maui invested heavily in SLARS in the months leading up to the market failure.

Different Responses

Despite the similarities between Maui and the state, there have been striking differences in how they responded to the SLARS debacle. For example, the state continues to defend its investment. “The one thing that gets lost in this whole discussion about ARS,” says Scott Kami, “is that the securities themselves are very sound investments. There hasn’t been any default on them, and we continue to get all our interest paid when it comes due.” Moreover, he says, the yield on the state’s ARS, approximately 1.9 percent, is higher than that earned by the state’s other investments. He points out the yield on 30-day CDs is almost zero.

Kawamura takes another tack. “I think people have put too much emphasis on the write-down,” she says. “Everyone thinks we’ve lost money. We have not.” She acknowledges that accounting principles required the state to estimate an impairment on its SLARS holdings. She also admits that if the state were to sell its holdings today, it would likely incur an additional $250 million loss. But Kawamura views these as purely paper losses. “That’s assuming that you’re going to sell,” she says. “Of course, we haven’t sold, and we don’t intend to.”

But Maui County treasurer Suzanne Doodan is not convinced by the state’s arguments. “I spouted those same lines for the first few months,” she says. “But these are no longer short-term instruments; you have to compare them to 30-year investments.” So, while the state’s 1.9 percent yields on SLARS may look good compared to current rates for bank repos or short-term CDs, they’re low even compared to the 4.75 percent yield on a 30-year U.S. Treasury note. SLARS might have been attractive as short-term investments, but they are liabilities as long-term investments.

This difference in perspective led Maui to pursue a different strategy than the state. This January, the Maui County filed a federal lawsuit against Merrill Lynch, the broker that sold them the SLARS. (To see Maui’s lawsuit filing, click here to download the PDF file.) Like other institutional investors around the country, Maui alleges Merrill sold SLARS as “cash equivalents” even though it knew, or should have known, these investments were unsuitable for Maui’s needs.

The state declines to discuss whether it’s pursuing legal action related to SLARS. “We’re obviously letting our attorneys take care of reviewing our options,” says Kawamura. Tung Chan, commissioner of securities at the Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs, acknowledges receiving complaints “against these companies – Citi and Merrill – related to ARS.” DCCA policy, though, is not to disclose the name of the complainant. It remains to be seen if the state, in steadfastly defending its investment in SLARS, has lost its opportunity for legal recourse.

“I wonder if they missed the date to file,” Doodan says. “I think it’s a two-year statute of limitations.”

A Better Way

There are other important differences between Maui and the state, according to Doodan. “To my knowledge, the state has only used two brokers for years and years and years,” she says. “In contrast, we go out to at least five, six, seven, eight brokers. And every few years, we go out and solicit new brokers.” It’s also interesting, she notes, that, while Maui has suspended doing business with Merrill, the state continues to use the same broker who sold them the SLARS as bond underwriters. (This same broker, Pete Thompson, of Morgan Stanley Smith Barney, played a key role in persuading the Legislature in 1998 to add SLARS to the list of acceptable investments for the state treasury.)

There is another difference between Maui and the state. To coordinate its investments and cash-management obligations, Maui uses sophisticated, Web-based software called QED. This program was specifically designed for treasury operations and automates many basic functions of a treasury. It continuously updates the status of investments, including the current value of securities. It also provides templates for more than 600 different reports, most of which can be produced almost instantaneously. This ease of reporting simplifies the supervision and oversight of the county treasury. That’s probably why more than 40 states and thousands of counties and smaller government entities use QED.

For its part, the state relies upon a software program called Microsoft Dynamics, which is primarily a program for enterprise solutions or customer contact management. Although it has been adapted to be used for financial purposes, it doesn’t address many of the specific needs of a state treasury. As one expert put it, “This is like hunting an elephant with a shotgun.” This may help explain the treasury’s failure to routinely produce the reports called for by its own investment policies. It may also explain why the state’s investment activities are largely tracked on manual worksheets or even handwritten calendars.

Most state treasuries are far more transparent and seem to sustain much more oversight than Hawaii’s. New Mexico – an apt comparison with Hawaii because of its population of 2 million people and treasury of about $5 billion – offers an excellent model for an efficiently run treasury. “I can tell you,” says chief investment officer Sheila Duffy, “we have a lot of oversight in New Mexico. And we like it.”

Structurally, that oversight takes the form of two standing committees. The Treasury Investment Committee, Duffy says, consists of treasury officials and two securities experts from private industry. The other oversight group, the Board of Finance, supervises the broader activities of the state treasury, which corresponds roughly with Hawaii’s Department of Budget and Finance. Neither group is passive.

“We have a once-a-month report, a book really, that we deliver to the Treasury Committee” and to Board of Finance, Duffy says. This substantial report – produced automatically using QED software – summarizes the treasury’s existing investments, including asset details, yields, and trends compared to a benchmark. These reports and the minutes from committee meetings are available on the treasury’s Web site, along with numerous other reports and resources. In contrast, although Hawaii’s state treasury policy requires monthly status reports for the director of the Department of Budget and Finance, this report hasn’t been prepared since 2007, according to the state auditor. Moreover, there’s no outside authority to review such a report.

The Cure

How can Hawaii improve its often informally structured, poorly supervised and cloistered state treasury? And what can we do about its extraordinary burden of SLARS?

As for the auction rate securities, the answer may be nothing. “For now, our liquidity issue is covered,” says Kawamura, by which she means that, as the treasury’s longer-term investments mature – and they’re allowed by statute to carry some investments out to five years – these are gradually replaced with the SLARS. And the state seems intent on either holding onto them until maturity – another 35 years, in some cases – or waiting until it’s possible to sell them at par. That might seem farfetched. After all, the allegations of fraud, negligence and collusion that have been leveled at the wire houses have stigmatized SLARS as an investment. But some believe the SLARS market will revive; Kami said as much in his Dec. 27 testimony at the state Legislature. Even Maui County finance director Kalbert Young holds out hope.

“I would point out,” Young says, “since the SLARS market failed in February 2008, there’s been a slow return of activity in this market.” He doesn’t mean the actual resumption of successful auctions – not yet, anyway – but that the underlying securities have started looking increasingly attractive to investors. “We’ve been getting calls from other institutions interested in buying our ARS,” he says. “Not at par, of course, but better than it was. Even Merrill Lynch was willing to purchase some.” Nevertheless, Young says, “we still want to pursue our legal filings.”

Improving Hawaii’s treasury operations may prove easier. It’s simple enough to look to the examples of other states, like New Mexico and New Jersey, that have modernized their treasuries. Software solutions typically come with extensive consulting services and are cost effective. (QED costs less than $100,000 a year, after the initial setup.) But the most important lessons probably come from history.

After the disastrous 1994 bankruptcy of Orange County, when the county treasurer’s wild, unsupervised speculation in risky derivatives cost the county over $2 billion, the California state auditor issued some familiar-sounding recommendations: Have a Board of Supervisors approve the treasury’s investment policies; appoint a committee to oversee investment decisions; require frequent, detailed reports from the treasurer; and establish stricter rules governing the selection of brokers and investment advisers.

Those sound a lot like the recommendations of the Hawaii state auditor. They’re also suspiciously close to the kinds of best practices employed in New Mexico. In other words: boring, boring, boring.

Risky Strategies

State’s mix of risky & safe, traditional investments

CASh

Demand Deposits1

$229,770,000

Cash with Fiscal Agents

$5,980,000

U.S. Unemployment Trust

$265,499,000

Investments

Investments Time Certificates of Deposit2

$618,192,000

U.S. Government Securities

$528,130,000

Student Loan Auction Rate Securities3

$1,006,975,000

Repurchase Agreements4

$1,151,620,000

Total Investments

$3,304,917,000

Total Cash and Investments

$3,806,166,000

1. The state routinely failed to reconcile bank statements. In addition, funds were often left in sub-accounts that did not earn interest.

2. At least five times, the state exceeded the 50 percent limit on CDs from a single issuer.

3. The state’s portfolio of SLARS remains at roughly 30 percent of its total investments.

4. Repurchase agreements exceeded the 70 percent statutory limit in four out of 12 months.

Source: State auditor’s report