More Than Just Farming

Manny Miles and Cheryse Sana were nominated for an award for “Employees that support farm owners and contribute to farm excellence” at this year’s Hawaii Agriculture Conference. Both are in their 20’s and co-managers at an organic farm in the community in which they were raised. They also represent an important path to the future of small-scale farming in post-plantation Hawaii.

Miles grew up helping his parents with their chicken farm in Waianae’s Lualualei Valley. He never thought of becoming a farmer until his dream of playing soccer at a Mainland university was scuttled by the cold reality of an Indiana winter. In 2002, a kupuna suggested he intern at MA‘O Organic Farms.

At the time, MA‘O (an acronym for “Mala Ai Opio,” which means “the youth garden”) was only a year old, still adjusting its business plan and starting to grow organic produce. As the public face of the nonprofit Waianae Community Redevelopment Corp., however, its mission was in place: to develop Waianae’s next generation of leaders.

When the rest of Oahu thinks of Waianae, sometimes all they consider is the poverty and homeless encampments along the beach, but before Western contact, Waianae was a self-sufficient region that produced enough food for its people while sustainably managing its resources. Lualualei, the largest of Oahu’s Leeward coastal valleys, was one of the area’s six ahupuaa, land divisions from mauka to makai.

MA‘O has a keen sense of place and its Hawaiian practices helped draw Sana there. She started as a high school intern in 2007, working at Waianae High School’s garden and the farm.

“I learned that it wasn’t only about farming, but it was a mix of organic farming and the Hawaiian culture,” she says. She became one of the farm’s college interns and finished her associate’s degree last spring at Leeward Community College. She’s now enrolled at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, pursuing a bachelor’s degree in Hawaiian Studies, while still working on the farm.

Miles’ and Sana’s successes at MA‘O contrast starkly with a more attention-grabbing local farm story: the alleged labor and human-trafficking abuse by Global Horizons Manpower Inc. and Aloun Farms.

“We need to be getting young people in the community, make them work hard, compensate them fairly and let them see there is a creative path to agriculture.”

– Gary Maunakea-Forth, MA‘O’s managing director

“We need to be getting young people in the community, make them work hard, compensate them fairly and let them see there is a creative path to agriculture,” says Gary Maunakea-Forth, MA‘O’s managing director. He says MA‘O’s nurtured the two farm managers, who in turn can oversee a farm and create more jobs. “They can do more than just work on a farm. They can run a whole operation, from the sales and marketing side all the way to the fundamentals of land prep and clearing.”

They’re also living examples of what many visionaries and politicians have been preaching to Hawaii for years: educating the community, growing our own food, honoring the host culture and supporting the local economy. And it’s all happening at a small farm in Waianae.

Growing Students

At its core is MA‘O’s college intern program. Open to high school graduates ages 17 to 24 who live on the Waianae Coast, interns work on the farm, and at farmers markets and other events. In return, MA‘O pays their tuition for a general education associate’s degree with a focus in community food systems from Leeward Community College. Required courses include organic agriculture, community food systems and Hawaiian studies. Interns also receive a $500 to $600 monthly stipend.

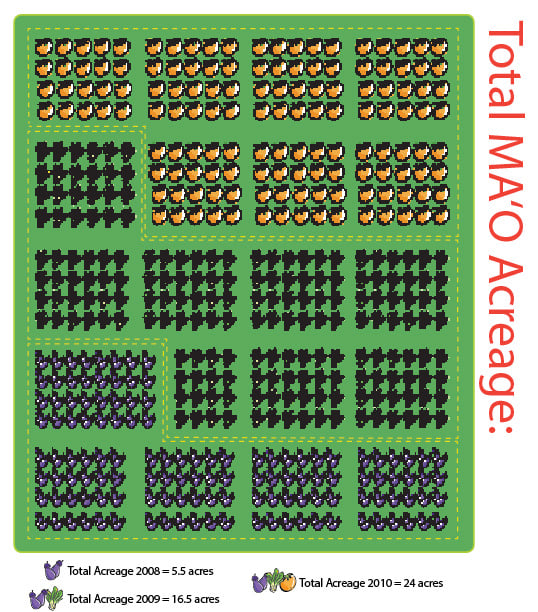

The farm currently has 32 interns, but, as it adds land, it will add interns. Maunakea-Forth believes the farm can effectively handle two students per acre. The farm leases 5 acres, owns 11, and, at this writing, was buying seven more. MA‘O also operates youth gardens at Waianae High and Waianae Intermediate schools.

The farm grows 45 types of fruits and vegetables, including leafy greens such as arugula and kale, root vegetables such as radishes and beets, and fruits such as mangoes and tangerines. Its produce can be found at Waianae’s Tamura Superette, health food stores like Umeke Market and Whole Foods, and fine-dining restaurants such as Alan Wong’s and Nobu Waikiki. MA‘O also has been a mainstay at the popular Kapiolani Community College farmers market. The wide variety of plants and points of sale also prevents the farm from becoming too dependent on one source or, as they say, putting all your eggs in one basket.

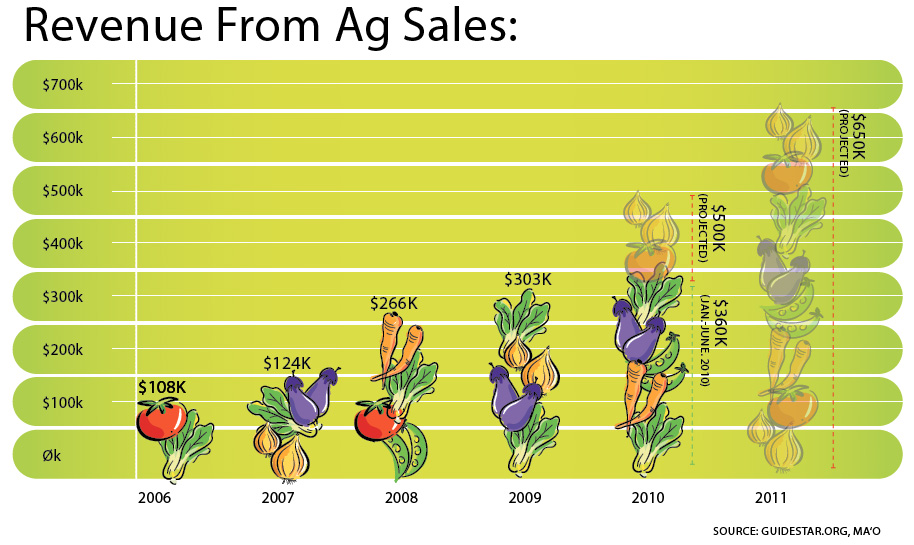

As a nonprofit, the Waianae Community Redevelopment Corp. applies for grants and relies on outside funding to run its programs. The profitable farm operation also attracts funding, which it uses to buy more land and teach more interns, which yields more produce, and so on. “The fact that the farm generates net profits, which can be used to offset the costs of their other programs, which would typically require support from charitable gifts, makes the program more sustainable and provides leverage for funders,” says Kelvin Taketa, CEO of the Hawaii Community Foundation. HCF and its clients have provided more than $1 million to MA‘O since 2003. Two years ago, the Omidyar Ohana Fund at HCF helped MA‘O expand to 16.5 acres, Taketa says.

The Ulupono Initiative, also backed by billionaires Pierre and Pam Omidyar, counts MA‘O as one of its investments. One of Ulupono’s missions is to fund for-profit and nonprofit ventures to increase local food production. “MA‘O was not only a great choice to get the ball rolling on increased production of organics, but I’m very excited about their mission of helping the local kids in the area,” says Robin Campaniano, general partner at Ulupono. “Part of our investment strategy is to not look at just one-shot deals, but to see whether or not the venture can be sustainable and replicable. We’re hopeful that the MA‘O model can exist and can be used elsewhere.”

Part of the farm’s appeal is its respect for and practice of Hawaiian culture. There’s a traditional altar built by the interns and, at the monthly open house and volunteer workday, the interns stand opposite the volunteers and say a Hawaiian chant before entering the farm.

Neil Hannahs, who was born in nearby Maili, is director of the land assets division at Kamehameha Schools and a MA‘O board member. He says the farm has made a “very practical connection to the business of agriculture and reaching out to the young people of Waianae, (while) appealing to our cultural heritage of being associated and born of the land.”

Co-producers, Not Consumers

MA‘O stresses that its funding and support is “relationship-based.” It refers to clients and customers as “co-producers,” a term coined by the Slow Food movement. In this way of thinking, co-producers are not just end consumers in the food industry; they take an active role in caring where their food comes from.

Co-producers are big supporters of MA‘O’s subscription program: For $32 a week, you get a box of whatever vegetables and fruits the farm harvests that week. MA‘O’s community of co-producers is also apparent on Monday evenings at the V-Lounge on Kapiolani Boulevard, in Honolulu’s urban core. At the pizzeria and bar, the crowd ranges from young hipster foodies and businessmen in aloha shirts to young families and their children.

Kamuela Enos, MA‘O’s community development director, says it chose the V-Lounge partly to change people’s preconceptions of the local organic food scene. Other participants – such as Wow Farms, an organic tomato producer in Kamuela on the Big Island, and Hamakua Mushroooms – help make the gathering a self-proclaimed “Bar-mers Market.”

Subscriber Michelle Moku collects her weekly supply of MA‘O produce outside the V Lounge, a hip Honolulu pizzeria and bar. MA‘O chose the location partly to challenge stereotypes about the people who eat organic food. | Photo: Rae Huo

One of MA‘O’s staunchest advocates and co-producers is restaurateur Ed Kenney, chef and owner of Town and Downtown restaurants. He opened his first restaurant in 2005 with the concept, “Local first, organic whenever possible, and with aloha always.” He runs it with the social entrepreneurship model of people, planet and profit. “Buying local just goes along with it,” he says. “What MA‘O is doing for the community, it all goes hand in hand. And then the bottom line, it ends up being profitable, as it is for them.”

Kenney first heard of MA‘O when he was chef and catering general manager at the YWCA at Laniakea. At the time, MA‘O had only one vegetable bed in the ground, and Kenney asked the farm to bring him a box of veggies a week. He remembers asking Maunakea-Forth if MA‘O could grow beets. “They brought a box in, and Gary goes, ‘I got you beets, mate!’ and I look in there and there’s one beet!” Kenney recalls with laughter. “He was just so excited, and we made use of it.”

MA‘O’s mission: “Social entrepreneurship, growing organic food and young leaders for a sustainable Hawaii.”

Kenney uses the produce in his restaurants’ dishes and works at MA‘O’s fundraisers. He also hosts each new group of MA‘O interns so they can taste the food they have harvested, enjoying a true farm-to-plate experience. The relationship is no longer just farmer and chef, but friends, Kenney says. “I was at the right place at the right time.”

The same can be said about MA‘O’s success. For a time, MA‘O operated and sold its produce at Aloha Aina Cafe on Farrington Highway in Waianae, ironically across the street from McDonalds. It was a tough sell and averaged $300 to $400 a day. The local market wasn’t ready for it, and the farm closed it after three years to focus on farming.

The farm has benefited from people’s growing awareness and curiosity about what they eat. In the past 10 years, the Hawaii Farm Bureau-sponsored farmers markets started at KCC and have expanded to more locations; more restaurants committed to local produce have opened; Down to Earth and Whole Foods have expanded in Hawaii; shows like “Iron Chef” have made cooks into celebrities; books like “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” and films like “Ingredients” have made people more aware of their food sources; and the green movement, which includes food sustainability, has gone mainstream.

It can be argued that MA‘O works and gets some breaks because it’s a nonprofit, but its supporters say that misses the point. “Their mission first and foremost is to raise and build a community, and they do it through agricultural activity,” says Neil Hannahs. “To support themselves, they recognize that they can’t be reliant exclusively on grants and the largesse of others. They have an earned-income opportunity with their agribusiness to support the mission of community building.

“I don’t think they want to turn that on its head and say, ‘We’d rather be a for-profit business that trickles some of our net proceeds or profit to the community.’ They really flip it the other way, saying, ‘This is about building community capacity and we can do it in a way that is very culturally aligned by being good farmers and touching and healing the land and working the land.’ ”

Farming Future

MA‘O may not provide the full blueprint for the future of local agriculture, but its supporters say it is part of the solution.

“The traditional subsistence or mom-and-pop farm, I think there’s still a place for it, but it didn’t lead us to feeding ourselves or growth. I think that’s why we always fell back on the industrialized farming model,” says Kenney. “Whereas, if someone can be creative in how they operate, we can think of new ways to feed ourselves, and that’s exactly what I think MA‘O has done.”

“I think we’ve developed a model that’s got pieces other people can replicate, and I think is really important in Hawaii ag in general,” says Maunakea-Forth. “People can argue that Hawaii ag’s going to go industrial and GMO and whatever, but I think this model – maybe not the entire model, maybe not setting up a nonprofit completely – but (other farmers can) use some of the pieces.”

Hannahs certainly hopes Kamehameha Schools can learn from MA‘O. The trust’s strategic agricultural plan identified 88,000 of its acres as prime agricultural land, and its goal is to create a sustainable food system in a post-plantation era. Doing so requires land planning and people planning, Hannahs says.

“That’s where I thought MA‘O was way ahead of the pack, in terms of engaging people in the business of farming,” he says. “Most of the farmers that we see out on our land today are elderly, in the advanced part of their lives and careers. When we’ve looked to who their successors will be, it’s really uncertain, and I think a lot of labor is imported in this state. That’s a very complex issue, but what we are particularly looking for is not necessarily field laborers so much as agri-business entrepreneurs, and how do you find those opportunities in organizations like MA‘O or in individual local people, especially our Hawaiian stakeholders.”

In the future, MA‘O hopes to build new relationships, such as with the University of Hawaii-West Oahu, which has shown an interest in building a community agriculture program at its new Kapolei campus. Another new relationship is with Waianae High School’s Searider Productions, called Kauhale, which was recently awarded a $4 million grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

On a larger scale, MA‘O hopes to raise awareness of Hawaii’s food and economic security. “The best thing we have going on for us is that we don’t necessarily have to produce more than what we can eat,” says Maunakea-Forth. “We’ve got a million people locally who want to eat and we’re only feeding them 10, 15, 20 percent of what they want to eat. So if we fill that gap in first, we’re talking about hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of market potential right there. Then we’re talking about 7 million people coming here a year as well. We have a captive market, that if we structure agriculture right and get people psyched about it, they might want to work in the sector.”

His biggest concerns are stories of human trafficking to supply labor to local farms. “It’s not making farming more attractive for people to want to work in it.”

The ultimate goal of the nonprofit is to redevelop Waianae, and it will look closely at the 2010 and 2020 Census data to see if it has made progress. “Ten years down, we’re hoping the poverty rate will be different, people will be making more money, the number of people in the community with a college education will have changed quite radically, and some of those socio-economic deficits, we’ll be looking at them having been improved,” Maunakea-Forth says.

He knows at least two people who will make a positive difference. Farm co-manager Cheryse Sana would like to eventually earn a master’s degree and become a teacher. She also has influenced her family to eat healthier (with produce from the farm, of course).

Miles is looking forward to a lot of things. He’s working on his associate’s degree, he owns a home in the valley where he grew up, and he and his wife, Summer, MA‘O’s director of education, are expecting their first child. Eventually, he’d like to buy an acre of land in the valley and run his own farm. He remembers helping his family raise chickens for eggs, which they sold to neighbors, and says, “What we did back then is what we need to do now.”