How to Get Startup Paradise to the Next Level

Hawai‘i’s startup community creates and nurtures plenty of early stage innovative companies but loses them before they scale into national and global players. Should we be happy with that storyline or should we try to change it?

Twenty years ago, Hawai‘i’s startup community was a barren sector with few resources to lift budding entrepreneurs with plans for innovative, fast-growth companies. That community is now filled with events, coworking spaces and programs that help these people build their nascent businesses and connect with investors, mentors and other partners.

That’s quite an accomplishment for an island state in the middle of the Pacific. Many entrepreneurs and accelerator programs have capitalized on Hawaiʻi’s strengths by concentrating on renewable energy, sustainability and Hawaiʻi-branded consumer products. And $468 million of venture capital was invested in companies that were founded here or participated in local accelerators from 2010 to 2018, according to a report commissioned by the Hawaii Strategic Development Corp.

But many challenges remain in this community, dubbed Startup Paradise by its advocates, including a shortage of talent and funding options that innovative startups need, plus a high cost of doing business. So some startups – even successful ones – leave the Islands. And those challenges are further exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic that gripped the Islands at the time this story was being completed.

Several experts interviewed for this story say the Aloha State has proven to be a good place for entrepreneurs to create companies and get initial support, but they hope Hawaiʻi can eventually become more than that.

“Are we a community and a state that is charged with developing the economic communities of other states, or are we charged with elevating our own community?” asks Omar Sultan, managing partner of Sultan Ventures, who also runs an entrepreneurship center, a youth accelerator program and an investment readiness program. “And I ask that because it seems to me that we’ve gotten very good at planting seeds here in Hawaiʻi that end up growing and maturing in other economic regions and other states.”

Efforts are underway to strengthen Hawaiʻi’s startup community. The Hawaii Technology Development Corp. (which inherited the now-defunct HSDC’s mission, assets and portfolio) manages community innovation hubs on Oʻahu and Maui, funds some accelerators and provides grants to local businesses. And the Innovation Economy Team of the Hawai‘i Executive Collaborative is working to support Hawaiʻi’s startups through investments and mentorships.

Rich Wacker, chair of the team, says the local entrepreneur community is tenacious, durable, committed and surprisingly resilient.

“Hawaiʻi is not an easy place to do business, we know that, and despite that people have a reason that they’re here,” says the president and CEO of American Savings Bank. “There’s a commitment to growing the sector and getting things (done), whether it’s around sustainable energy, whether it’s around ag tech stuff or around energy efficiency and all the different spaces.”

Budding Ecosystem

Susan Yamada, director of UH Ventures, which fosters innovation at UH, says milestones in the growth of Hawaiʻi’s startup ecosystem include the formation of Hawaiʻi Angels, a network of seed-level private equity investors; the creation of a controversial tax credit program that incentivized companies to invest in high-technology companies and helped create startups; and the launch of the HI Growth Initiative, which used a $21 million investment of state and federal monies to create local accelerators and support a state investment program.

Along the way, local entrepreneurs were supported by growing numbers of community events, innovation hubs and coworking spaces.

“We’re seeing a tremendous amount of progress where I don’t think it’s unusual now if people are saying that they want to do a startup or they’re working on a startup. … There are all these startup communities that were never there 20 years ago, so I do think it’s more established, it’s become more mainstream, and we’re moving definitely in the right direction,” Yamada says.

HTDC aims to grow Hawaiʻi’s technology industry by developing talent and providing capital and infrastructure. Len Higashi, its acting executive director, says HTDC, the larger business community and state Legislature are coming together to support the growth of entrepreneurship. HTDC manages the Maui Research and Technology Center and the Entrepreneurs Sandbox, which are meant to incubate innovation, provide resources to entrepreneurs and bring people together.

HTDC also provides funding to some accelerators, with the yearly amount set by the state Legislature. The agency received $1 million in fiscal year 2017-18, $1.5 million in 2018-19 and $300,000 in 2019-20. This year, the agency provided funding to Elemental Excelerator, Mana Up, XLR8HI and Blue Startups.

The agency also awards grants to local technology and manufacturing companies to help them develop new products and expand their production capacity. In April, the agency awarded $1.4 million through its Small Business Innovation Research program and about $486,000 through its Manufacturing Assistance Program. The state’s goal, Higashi says, is to create a sustainable ecosystem with thriving companies and many opportunities for people to contribute.

According to the report, “Venture Capital in Hawaiʻi 2010 to 2018,” Hawaiʻi is making progress in helping startups launch and grow. Investors delivered $468 million of venture capital – a type of financing investors provide to startups – to companies that were founded in Hawaiʻi or have business nexuses in the Islands (such as participating in local accelerator programs or having kamaʻāina founders with headquarters outside of Hawaiʻi). About 53% of that money was invested in 128 unique Hawaiʻi-based companies; the rest was invested in 53 Hawaiʻi-related companies.

Company founders attend the annual Mana Up alumni retreat. This activity is designed to help participants understand that we all view the world through different lenses and how to have productive communication despite these differences. | Photo courtesy of Mana Up

Donavan Kealoha co-authored the report and is a director at Startup Capital Ventures, an early-stage venture capital firm with offices in Honolulu and Menlo Park, California. The report was commissioned by HSDC to learn how local companies received funding. He says, generally, companies that participated in accelerators raised more capital because their businesses were more developed.

Meli James, president of the Hawaii Venture Capital Association, says Hawaiʻi has yet to reach the point where it’s reaping the full fruits of its labor, but the work around entrepreneurship is important because it will help create high-paying jobs and a sustainable livelihood for current and future generations.

STARTUP DEFINITIONS

Accelerators are investor-readiness programs, says Peter Rowan, executive director of UH’s Pacific Asian Center for Entrepreneurship. They’re meant to accelerate the growth of startups by helping entrepreneurs develop their business models and connect with mentors, investors and other resources. These programs typically invest in participating companies in return for an equity stake in them and are cohort-based; participating companies “graduate” through the programs in a specific time to make room for new cohorts. Startups often receive their first funding from accelerators, he adds. Some local accelerators include Elemental Excelerator, Blue Startups and UH Ventures Accelerator.

Incubator is a term sometimes used to refer to accelerator programs, though the difference is that incubators typically do not invest in startups and instead focus on mentoring and introducing entrepreneurs to resources, says Vincent Kimura, lead founder and CEO of Smart Yields, a Hawaiʻi-based startup. Len Higashi, acting executive director of the Hawaii Technology Development Corp., says some programs also operate as hybrid of the two. One example is the Purple Prize, an innovation challenge run by the technology education nonprofit Purple Maiʻa. Olin Lagon, co-founder of Purple Maiʻa, says the Purple Prize has accelerator and incubator elements to its program. The six month-program is filled with workshops and projects to help entrepreneurs refine their ideas and learn about pitches, marketing and financing; the program also invests in some participating companies.

Angel investors provide funding to young startups. Darius “Bubs” Monsef, an entrepreneur and angel investor from Hawaiʻi Island now living in Portland, says an angel investor is an individual who can write a $25,000 to $50,000 check to an entrepreneur after a couple of meetings over coffee.

“That’s what you need in the earlier stage because the idea is not really a thing,” he says. “And you can’t run due diligence, you can’t have a three-year plan; you just got to hear somebody’s idea and trust they seem like the right person to be able to pull it off.”

Chenoa Farnsworth, managing director of Hawaiʻi Angels and managing partner at Blue Startups, says funding from Hawaiʻi Angels is often the first money that startups receive after graduating from Blue Startups.

Regional Strengths

Some local entrepreneurs – especially those working in clean energy and sustainability – see Hawaiʻi’s isolation in the middle of the Pacific Ocean as a strength, not a challenge.

Olin Lagon founded his latest startup, Shifted Energy, after seeing the state’s push for renewable energy was excluding renters, who typically cannot afford electric vehicles or solar panels. His startup now develops grid-interactive water heater systems.

The “Venture Capital in Hawaiʻi” report says most venture capital invested in Hawaiʻi startups between 2010 and 2018 was in utilities (around energy production, infrastructure, storage or services, or commercial services), information technology, health care and industrials sectors.

Dawn Lippert, CEO of Elemental Excelerator, says Hawaiʻi offers many significant opportunities that startups are capitalizing on. Elemental Excelerator is a Honolulu-based accelerator that focuses on transportation, agriculture, water, energy and sustainability companies. Eighty-six of Elemental Excelerator’s 99 portfolio companies have headquarters outside Hawaiʻi but found the Islands to be a good place to test their solutions.

On Kauaʻi, the newly created Common Ground Accelerator is working to help small, Hawaiʻi-based food and beverage businesses grow. Adam Watten, co-director, says the island has many innovative people and ideas, but it lacks a support system to help them scale.

Co-directors Brian Halweil, left, and Adam Watten of Common Ground Accelerator on Kauaʻi | Photo courtesy of Adam Watten

“If agriculture is going to remain viable in Hawaiʻi, then we need to figure out a new model,” he says. “And scaling these businesses and developing products that have appeal elsewhere on a national market or a global stage is really the way we’re going to be able to help the system.”

Mana Up is another accelerator leveraging Hawaiʻi’s strengths. Its goal is to build the next 100 Hawai‘i-based product companies earning $10 million or more in annual revenue. Co-founder James says one reason she started Mana Up was to broaden the view of innovation and entrepreneurship to include small businesses that leverage Hawaiʻi’s regional strengths.

“Hawai’i was built on small businesses,” she says. “Why would we turn our backs and not be creating the resources, mentorships, access to capital” for companies to grow and thrive here?

She adds that Mana Up’s businesses stay in the Islands as they grow. One of them is Wrappily, a Maui-based business that participated in Mana Up’s fall 2019 cohort. Sara Smith, Wrappily’s founder, launched the business in 2013 after learning that none of the state’s recycling centers accepted traditional wrapping paper. She found a more sustainable model: create eco-friendly, recyclable wrapping paper using underutilized newspaper printing presses. She grew her business organically, starting with Maui retailers who were willing to partner with her. Today, her products are sold online and at retailers across the Islands, on the Mainland and, most recently, in Japan. While Wrappily’s paper is milled and printed in Washington state, Smith says, she’s committed to staying on Maui.

“Every year my husband looks at me like, ‘You’re not going to ask us to move are you?’ ” she says with a laugh. “And no, I mean Maui is my home and I am tremendously connected to being here and logistically, yeah, it would probably be a lot easier if I lived (in Washington state), but I have great partners and personnel in place there that are my eyes and ears, and we’re making it work.”

Greg Kim, an attorney and founder of Vantage Counsel LLC, has worked in Hawaiʻi’s entrepreneur community for decades and says small businesses are helping to grow the state’s economy, even if they’re not on high-growth paths like innovative startups that aim for national or global impact. He’s even changed his legal practice to focus less on venture capital and more on supporting the success of conventional local small businesses.

HOW STARTUP PARADISE GOT ITS NAME

Len Higashi, acting executive director of the Hawaii Technology Development Corp., says Startup Paradise is the name the startup community gave itself. The term “Startup Paradise” was first used during a 2012 Startup Hawaii conference, says Chenoa Farnsworth, managing director of the Hawaiʻi Angels and managing partner of Blue Startups. Someone in the audience tweeted it as a hashtag and it stuck, she says.

Heavy Challenges

It’s hard enough to start a business: 20% of new businesses in the U.S. don’t make it to their second year, and little over half are still around to celebrate their fifth anniversaries, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In Hawaiʻi, innovative startups are also challenged by limited access to talent and funding opportunities.

“Startups, especially in demand of technical talent and lower supply-chain-related capital expenditures, frequently relocate to more mature entrepreneurship clusters to meet these demands and to gain greater access to venture capital, first-adoption opportunities and better exit opportunities,” wrote the authors of the “Venture Capital in Hawaiʻi” report.

Chenoa Farnsworth, managing partner at the Blue Startups accelerator in Honolulu, says that accelerators are partly intended to help build and attract talent. Blue Startups purposely picks half of its companies in each cohort from outside the state to diversify the accelerator’s returns and to encourage locals and nonlocals to learn from one another.

Vincent Kimura, lead founder and CEO of Smart Yields, which helps farmers protect their crops and increase their yields using sensors and crowd-sourced data, says one of his biggest challenges was building a team that could help him bring his ideas to life. Those challenges are exacerbated by the state’s high cost of living, relatively small population and the fact that startups can’t pay market wages.

Plus, startups often reach a cap on how much money they can raise locally. “We’ve done a good job of getting companies to a certain threshold, but then you hit this gap,” Kimura says, adding that the gap is an investment gap.

In agreement is Kealoha, who has co-founded a couple of local companies and the Purple Prize innovation competition and mentoring program. Kealoha says there are examples of startups that have stayed and raised tens of millions of dollars locally, but those startups tend to be run by more seasoned entrepreneurs who may be viewed as more credible to local investors.

Chenoa Farnsworth, managing director of Hawaiʻi Angels and managing partner at Blue Startups | Photo: Aaron Yoshino

One challenge is engaging Hawaiʻi’s wealthy investors. Real estate has yielded lucrative results for them, so there’s not a big drive to do anything different, says Farnsworth, who is also managing director at Hawaiʻi Angels, a group with 50 members that has invested about $50 million in over 100 companies since its founding in 2002. For the last decade, the angels have invested an estimated $2 million each year.

Andrew Fowers, co-founder of Shaka Guide, a GPS-based tour app, says the main funding sources for early-stage local startups are local accelerators and Hawaiʻi Angels. The state needs more of these early investments, he says, because they help startups become healthy enough to raise money from the Mainland or elsewhere. His startup participated in Blue Startups in 2018 and was later able to raise funds from Japanese investors.

Another challenge is that Hawaiʻi lacks a critical mass of seasoned, successful entrepreneurs with the capital to invest in the next generation of startups, James says.

Darius “Bubs” Monsef is an entrepreneur from Hawaiʻi Island living in Portland. Four of his startups were founded on the Mainland, including his most recent one, called Brave Care, a pediatric urgent care clinic in Portland. He raised $6 million for Brave Care in the last year and says he couldn’t have built that company in Hawai‘i nor raised that money in the Islands.

He is an angel investor in companies based on the West Coast and in Portland and says any startup would have a better time not being in Hawaiʻi. “I think they leave at the point where they find it painful to continue growing, either hiring or fundraising,” he says.

He left Hawaiʻi a couple of years ago so he could continue to build startups: “I have exits and I have access to capital, and it’s still hard to build companies for me in Hawai’i, so why stay there just to fight upstream? I’ll go where it’s most supportive.”

Monsef adds a caveat: He says people who are passionate about building something for Hawai‘i and its future would naturally stay in Hawaiʻi. For instance, Smart Yields is based in Hawaiʻi and has a global mission. It has participated in accelerators and incubators locally and elsewhere so it can test its solutions and enter new markets. As it grows, its leader says the startup is committed to staying in Hawaiʻi.

“We looked at it, like, I want to be here,” Smart Yield’s Kimura says. “Our goal was and has always been to support Hawaiʻi.”

Peter Rowan, executive director of UH’s Pacific Asian Center for Entrepreneurship, says he disagrees that companies are moving away because of a lack of capital. His experience as an entrepreneur, investor and in corporate finance has shown him that money follows good ideas and good deals.

“I’ve never seen a really good entrepreneurial idea that had a lot of traction and had a good growth prospect, I’ve never seen them not be able to raise money if they had all the elements that an investor is looking for, regardless of where they are,” he says. PACE runs the UH Ventures Accelerator, which aims to support ventures started by UH students, faculty, staff and alumni.

UH Ventures’ Yamada adds that sometimes startups have legitimate reasons for moving away, such as to be closer to customers or supply chains. “You have to go where your business is going to be most successful,” she says.

Shifted Energy’s Lagon adds that it also makes sense for startups to move some of their operations outside of the state. Shifted Energy moved its legal entity to Delaware and its production is in Georgia.

“There’s always a role to be based in Hawaiʻi,” he says. “… But there’s also things that would make so much more sense to move outside of Hawaiʻi – production, marketing, fundraising, things like that. It’s just all about finding that right balance.”

As Hawaiʻi pushes its startup ecosystem forward, Sultan says, another challenge is the state’s risk-averse culture. In other places, failure is considered a learning experience rather than something shameful.

“I don’t know that we have that culture embodied here in Hawaiʻi just yet. But as a community we are working on trying to change that,” he says.

In addition, he thinks the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on the state’s economy will exacerbate the challenges that local startups and entrepreneurs face.

Farnsworth says it’s too early to say whether the Hawaiʻi Angels will invest its normal amount this year: “There is a direct correlation even more so with angel investors between the markets and their appetite for investing. As markets remain volatile and down, a lot of our members lost a lot of wealth, at least on paper, and that means their allocation for this category of investing, known as alternative investing, shrinks.”

Yamada thinks it’ll be difficult for startups to find funding and get any attention unless their solutions are catered towards the new coronavirus-created reality. For example, startups that offer streaming, delivery and online workforce productivity services might find opportunities and do well, but, overall, entrepreneurs will need to be more creative in how they fund themselves, she says.

Future Vision

Kimura says many people and organizations have helped to push Hawaiʻi’s startup ecosystem forward, but Hawaiʻi needs to do more to support its local startups and set a clear vision for what it wants this sector to look like.

“All these friends and entrepreneurs … everyone moved away,” Kimura says. “And we’re all talking about it, too. We’re all talking about the frustrations.”

Part of helping Hawaiʻi’s startup community means addressing the state’s larger challenges regarding its high cost of living and lack of affordable housing.

One of the frustrations, according to state Rep. Angus McKelvey, who has been in the Legislature since 2006 and is the chair of the House Committee on Economic Development and Business, is that the Entrepreneurs Sandbox in Kakaʻako was meant to be a space for entrepreneurs, but instead seems to serve as corporate offices for large businesses.

According to HTDC, only three startups have offices at the Sandbox, along with innovation and tech-focused teams from several large corporations. HTDC’s Higashi says the Sandbox is meant to spur collaboration. A recent example is the TRUE Initiative, which aims to foster technology innovation and develop needed workforce skills. TRUE is an acronym for technology readiness user evaluation. The initiative is housed at the Sandbox and its launch event brought together startups, business leaders and legislators, Higashi says.

Opinions are mixed on what Hawaiʻi’s startup community should look like in the future. Despite Hawaiʻi’s challenges, Lagon says, the state is a great place to come up with ideas and quickly test them, get them to market and scale. The fact that people leave is a good thing, he says, because companies that don’t have natural markets here can’t be forced to stay.

Farnsworth says some of Blue Startups’ portfolio companies are doing work around the world, and that benefits Hawaiʻi by putting it on the map as a place where companies can be built.

“I think we need to view success through the lens of, ‘Are we creating competitive global companies that start here even if they don’t end here?’ ” Farnsworth says. “I think that plays an important role in inspiring our children to be entrepreneurs and creating wealth that gets circulated back into our economy. These companies even if they achieve success elsewhere, those founders come back and reinvest in Hawaiʻi. So it all pays in the end.”

But Kim, the attorney, says he’s unsure that being a good place to seed companies is a good industry position for Hawaiʻi because the state wouldn’t benefit from its efforts to help companies grow.

Sultan echoes a similar sentiment: “Are we trying to be a cookie cutter model of other regions? Like everyone references Silicon Valley. There is only one Silicon Valley. And is that really what we want to emulate? Or do we want to lean on our own strengths? Do we want support programs and initiatives to be place-based and region specific?”

Rowan says that Hawaiʻi puts itself at a disadvantage when it continues to compare itself to other, larger geographic regions with longer histories of innovation and entrepreneurship.

“I think we have to remember that Hawaiʻi is not the center of the universe. It’s a wonderful place, but it’s a small place,” he says. “There’s only 1.5 million people here, and it’s unfair to compare what we’re trying to create here with what’s being created in Silicon Valley or Boston or New York or Seattle. Those markets are so much larger.”

Growing Innovation

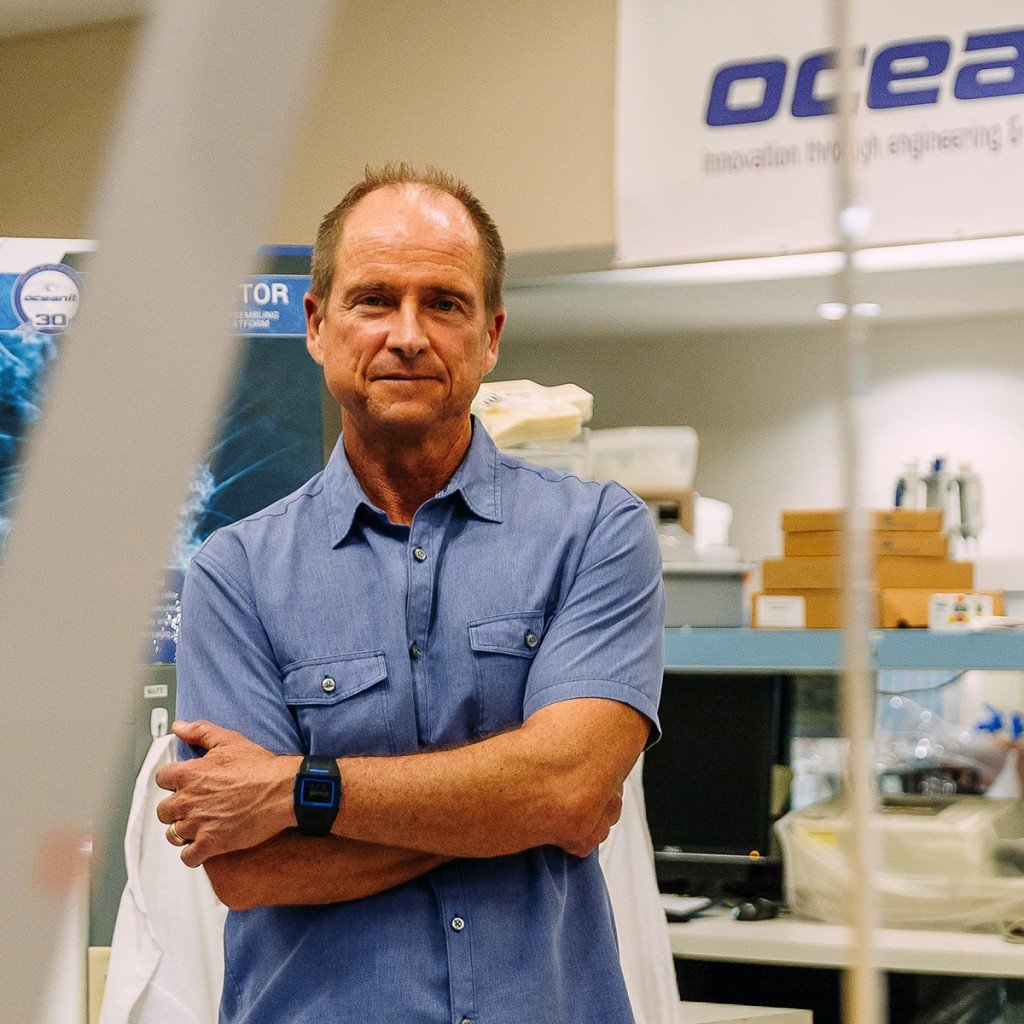

The coronavirus’ impacts on the state’s tourism industry have spurred plenty of discussion about what the next version of Hawaiʻi’s economy should look like. Patrick Sullivan, founder and CEO of local innovation company Oceanit, says people are starting to realize that Hawaiʻi needs to create an innovation economy that’s unique to the Islands.

Hawaiʻi’s strengths, he says, include its diverse cultures and its people’s abilities to work well with others. “I think it’s what makes Hawaiʻi innovation special as well,” he says.

“So I think over the years we’ve come to grips with trying not to be who we’re not and discovering who we are. And I think that’s something that I’m hoping this terrible time that the state is in and the struggle it’s causing gets people to kind of step back and say, ʻWait a minute, we can do this.’ ”

But developing successful innovation sectors takes a long, sustained investment from public and private sectors, Elemental Excelerator’s Lippert says.

“I think one of our key roles is to recognize this is a long game and one of the things we need to do as a community is to provide those pathways into innovation and learning in startups, in technology, in investment, etc., so that … people are getting exposed to it and can start companies here and elsewhere,” she says.

She adds that having key customers in Hawaiʻi is one way to encourage startups to stay or at least have a significant presence here.

Shifted Energy participated in Elemental Excelerator’s program in 2015 to install 499 grid-interactive water heaters at a housing complex on Oʻahu and in 2018 to scale its solution globally. Lagon, the CTO, says entrepreneurs often rely on the kindness of strangers who are willing to test solutions and help startups scale.

“That’s a very special thing that we can’t discount or not acknowledge,” he says. “This place, people call it the aloha spirit or something like that, there’s a lot to be said about that.”

To foster more of that, the Hawai‘i Executive Collaborative’s Innovation Economy Team is working on matching established companies with promising innovation businesses and entrepreneurs. Wacker, the team’s chairman, says one example is the partnership between the state Department of Transportation and CarbonCure, a Nova Scotia-based company that makes technology that infuses recycled carbon dioxide into concrete. The two worked together to test carbon-infused concrete on an H-1 construction project in West Oʻahu.

The group also plans build a community resource of mentors and to encourage more local investment for early-stage companies, which, Wacker says, will hopefully also attract money from elsewhere.

This work, he says, is meant to create engagement between traditional large businesses, the higher education research community and the entrepreneurial community – all of which are key to creating a vibrant innovation sector.

“I think part of what we’ve been able to make everyone understand is that if we want this sector to be a vibrant healthy sector here, we have to engage,” he says.

RELATED STORIES

- Start-Up Paradise

- The Best of Startup Paradise

- Talk Story with Chenoa Farnsworth

- Startup Weekend Honolulu condenses entrepreneurship into 54 hours

- Hawaii’s Tech Industry After Act 221

- Summer Camp for Student Entrepreneurs

- Talk Story: Omar and Tarik Sultan

- 5 Ways to Boost Local Innovation