Inventive Local Companies Can Apply for Federal SBIR Grants

At first glance, Hawaii Fish Co. in Mokuleia doesn’t look like a hotbed of innovation. For more than 20 years, owner Ron Weidenbach has run a simple operation, raising tilapia in floating cages in the deep waters of an old quarry that he leases from the state. It’s a picturesque setting. Nestled against the craggy Waianae Mountains, the 4-acre fishpond resembles an alpine lake, its shores blanketed in koa haole, its still waters reflecting the clouds overhead.

The operation seems decidedly low tech: a dusty gravel road and a few ramshackle outbuildings. Because he has a short-term lease, Weidenbach can’t get a loan to make improvements, so the fishpond doesn’t even have electricity for aeration. And at harvest, someone has to swim into the chilly water and tow the cages ashore by hand.

But Weidenbach is an inveterate entrepreneur and he has elaborate plans for Hawaii Fish Co. Those plans got a boost last year when he won two research grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture – one to develop a national marketing plan for pongee, a fish normally sold only in Chinatown, and the other to study the feasibility of a new wind- and solar-powered aeration system for fish farms. Both $90,000 grants were through the popular Small Business Innovation Research program. If his SBIR projects are successful, they could transform business for his company.

How It Works

SBIR, as the name implies, is a federal program designed to support research and innovation by small businesses. The 13 federal agencies with significant research budgets that participate in the program each set aside a minimum of 2.5 percent of their research funds for small businesses (rising to 3.2 percent over the next five years). The federal agencies range from the Department of Defense, which accounts for nearly 40 percent of all SBIR funding, to the Department of Agriculture and the National Institutes of Health, at 19 percent each, to minor players such as the Department of Transportation and Environmental Protection Agency. Every year, each agency (or sub-agency, such as DoD’s Department of the Navy or USDA’s Rural Development program) publishes a list of solicitations for technological issues it would like small businesses to address. Typically, agencies use peer review or special committees to select the winning proposals. The Small Business Technology Transfer program, or STTR, is a smaller, sister program for small firms that want to commercialize university-based research.

SBIR awards come in three phases:

• Beginning this year, Phase I awardees receive up to $150,000 for a six- to nine-month feasibility study of their innovations.

• Only companies that have successfully completed Phase I are eligible to apply for Phase II: up to $1.5 million for a two-year project to build a prototype or demonstration project.

• Phase III, which is typically unfunded, is commercialization, which is, as Weidenbach points out, the whole point of SBIR.

“Phase I is really proof of concept,” Weidenbach says. “Phase II is research and development to bring you up to the stage where private money can take you forward to commercialization.”

It’s not small change. In 2010, SBIR funding amounted to $2.5 billion. Over the past 30 years, the program has funneled at least $21 billion into small business R&D programs. About 120,000 individual awards have been made to more than 15,000 firms, generating more than 50,000 patents. At this pace, SBIR has supported the work of more than 400,000 scientists and engineers spread throughout every state in the country.

$119 million locally

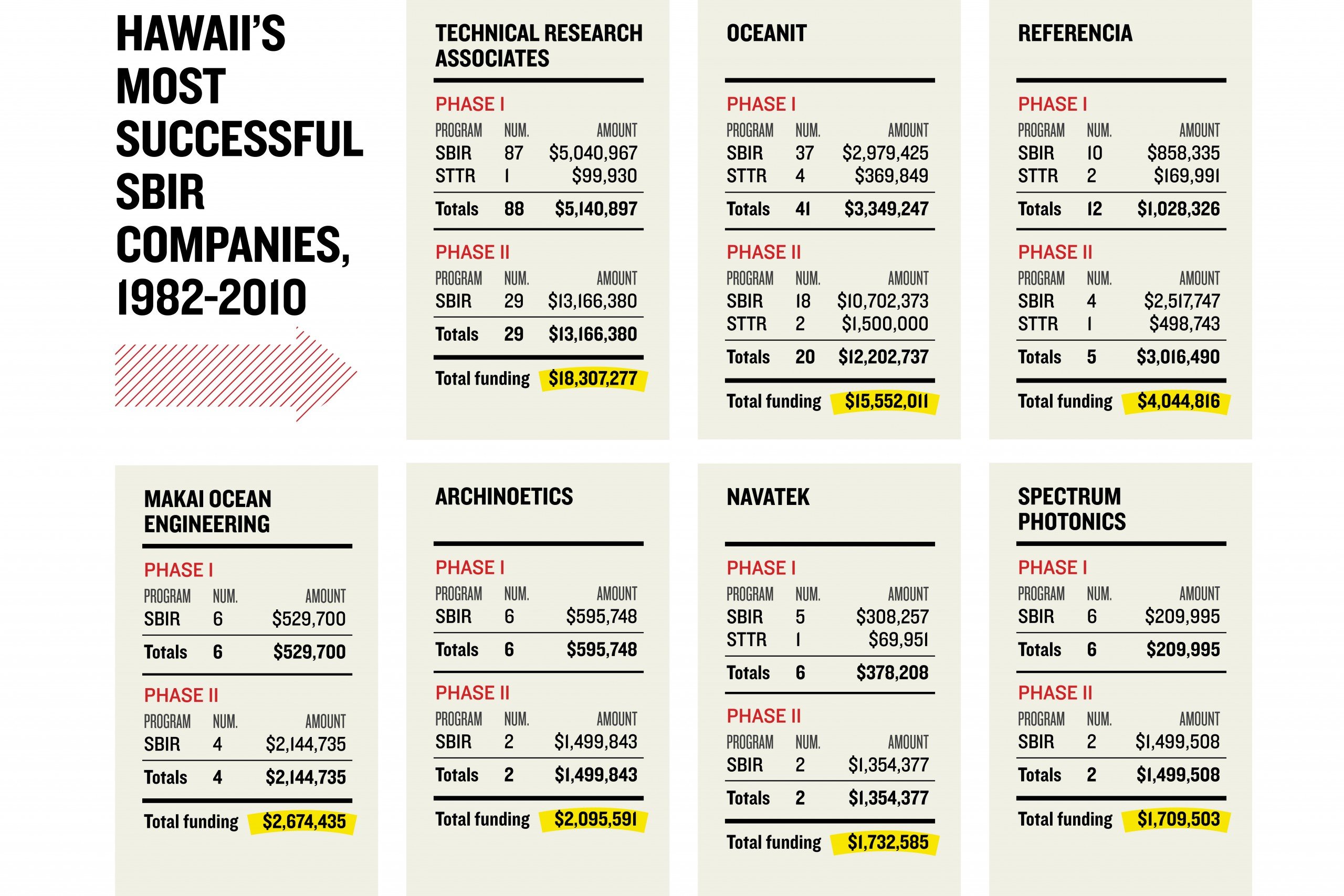

Hawaii gets its share of the SBIR largesse. Since 1982, when the program was established, local firms have received 545 awards worth $119 million. In fact, SBIR has become a critical source of R&D funds for Hawaii’s tech industry. Almost every successful tech firm in the state has received at least one SBIR award, and some of them have won dozens. These firms have become sophisticated at developing proposals and strategically integrating SBIR grants into their research. Smaller companies, like Hawaii Fish Co., can learn by studying how these experienced firms took advantage of the SBIR program.

One of the local companies most successful at getting SBIR and STTR funding is the tech firm Oceanit. Science and technology manager Ken Cheung says one of SBIR’s key advantages is that the companies retain all ownership of products developed through SBIR grants or contracts. The government retains only nonexclusive rights to the technology. With some agencies, such as DoD and the Department of Homeland Security, it’s sometimes even possible to receive Phase III funding to help with the commercialization of the product. Perhaps most attractive to a small tech company, the agency funding your research often ends up being your customer.

“Another thing that’s very powerful,” Cheung says, “is that, once you’ve competed for a Phase I – and especially for a Phase II – you’ve satisfied the conditions under the Federal Acquisitions Regulations so that, if the government wants to buy that technology, now it can do that without requiring an open competition. It can do a sole-source contract. On top of that, the government can’t take your design and have someone else build it; they have to buy it from you. That’s really powerful, because if your company is bought out by a bigger company – a Raytheon or a Boeing or a General Dynamics – those rights transfer to the company that buys you. That’s a big incentive.”

Companies like Oceanit take advantage of the tactical as well as the strategic advantages of SBIR. “Almost every one of our big projects had some SBIR help,” says Oceanit special projects manager Zubin Menon.

Perhaps more interesting, he points out, some companies string together several SBIR contracts to develop and refine complex technologies. He uses the example of FLASH, technology that Oceanit designed to help the military locate and identify hostile fire. “We started off, almost 15 years ago, with an SBIR project related to an airborne laser,” he says. “The idea was to shoot a directed-energy weapon – a laser – from a moving airplane. Because you have a lot of turbulence coming off an airplane, we developed a sensor to detect optical aberrations. That became a Missile Defense Agency technology; because that sensor operated at a very high speed, it turns out it’s very useful for looking at missile intercepts, so we got SBIR funding for that. Using that core sensor technology, we also got an Army SBIR to develop this hostile-fire indicator.” For those counting, that’s three Phase I and three Phase II grants. In addition, the Pentagon has helped Oceanit with non-SBIR Phase III funding to create some field units to test in action.

A company’s success with the SBIR program largely depends on how well it takes advantage of the program’s rules and procedures. For example, Cheung points out, each topic or RFP from the participating agencies has a unique point of contact, often the person who wrote the actual solicitation. After those topics have been announced, but before the official RFP is released, firms are permitted – even encouraged – to communicate directly with the point of contact.

“Up to a certain point, you’re free to email or phone the technical point of contact and ask them what they’re really looking for, what do they think of your idea, and they’ll give you feedback right away. So, we’re certainly going to get this guy on a conference call and ask him what he thinks of our approach. If there’s some resonance, we’ll go ahead; if they say, ‘No, you’re completely off base,’ we won’t waste our time.”

Weidenbach also carefully weighs SBIR’s risks, primarily that funding rarely covers a project’s full cost. “In Phase I, you almost always spend more than is covered by the grant,” he says. “So, if you’re thinking of SBIR as a way to make money, you’ve got the wrong impression. It’s simply a way to defray your research costs. There will almost certainly be significant out-of-pocket expenses. There’s also a significant investment of your time in the application process, which is really a high-risk proposition after all. Only 10 percent to 15 percent of Phase I applications are accepted. I guess your odds are better in Vegas.” In other words, he says, only go the SBIR route if you’re confident you’ve got something the world needs.

Getting It Done

Companies like Oceanit may fit the federal government’s definition of a small business – fewer than 500 employees – but it’s difficult to put them in the same category as really small SBIR awardees like Hawaii Fish Co. But Weidenbach’s operation isn’t unique. Another truly small business that has received SBIR funding is an educational-media developer called WEBFish Pacific. WEBFish president and founder Lynn Wilson was a sole proprietor when she was awarded a Phase II grant last year under the aegis of USDA’s Rural Development program. That makes her a real rarity in SBIR. But her project – creating an educational video to help improve oral health in rural communities – is a good example of how a small firm can use partnerships and collaborators to compete with larger, better-staffed companies. One point Wilson makes is that a company’s Phase I should flow neatly into its Phase II.

“You certainly want to build your case and come out with a Phase I that points to the need to build a full prototype,” she says. “For our Phase I, we developed some video samples and tested them against a print brochure and against video samples developed by a school of dentistry. We had nine focus groups with parents of young children. We did three through Head Start, three through a community health center here and three through a Hawaiian culture-based preschool.

“We’re in Phase II, now,” she says. “So we now have a set of short videos – about 50 minutes of video – geared specifically to parents and young children, and we’re evaluating those using the Early Head Start programs on the Big Island and Oahu.” In all, she says, the project evaluation involves a team of five research specialists and 20 home visitors in two organizations with more than 100 families. She ultimately expects to market her videos through Head Start.

It’s an elaborate process and, like Weidenbach and many SBIR awardees, Wilson expects to need an unpaid extension in order to finish Phase II. “If I was to do this whole process differently, I would make sure that I had the whole thing mapped out long before I put in my Phase I application.”

Bipartisan program

SBIR has always been a politically popular program. After all, it’s a way to direct federal funds into almost every congressional district under the cover of helping innovation and improving the economy. As Congresswoman Mazie Hirono points out, that’s particularly important now that earmarking is no longer available. So, even in these days of polarized politics, SBIR remains uncontroversial. For a sense of just how popular the program is, consider this: As part of the Defense Authorization Act that passed in December, Congress not only extended the SBIR program, it nearly doubled the size of both Phase I and Phase II awards. Perhaps more remarkable, SBIR was reauthorized for six years; previously, it had to be reauthorized every year.

Even before the reauthorization, Hirono had already introduced legislation to expand SBIR funding. “I also submitted testimony to the Small Business Committee, which had a hearing on small business innovation programs,” she says. “So it’s good. I was very pleased to learn that the Defense Authorization Bill had SBIR and STTR in it.”

SBIR is also popular with state politicians. For 22 years, Hawaii’s SBIR program, which is administered by the High Technology Development Corp., has offered matching funds to Phase I recipients, largely to help companies bridge the funding divide between Phase I and Phase II. Companies can use the funds to improve their Phase II applications – to buy equipment or pay for specialized staff.

Originally, the state program was a 50 percent match of Phase I funding. But, as HTDC business development manager Russell Au points out, there typically weren’t enough matching funds for all Hawaii awardees. “This past fiscal year, though, the state gave us $520,000, which is a $260,000 increase over the previous fiscal year.” He also notes those matching funds seem to have been a good investment, because Hawaii companies have secured about $62 million in Phase II funds and upwards of $64 million in private and other federal funds.

HTDC also supports SBIR by holding workshops and an annual conference. WEBFish, which received matching funds for its Phase I, was also given HTDC help with the complex application process. “The directions for the proposals are a little overwhelming,” says WEBFish president Wilson. “HTDC put us in touch with SBIR consultants and, in fact, funded 10 hours of work with them.”

Weidenbach adds that HTDC’s annual conference makes it possible for local firms to meet with the individual agencies’ SBIR program managers. All this is possible because, even in difficult financial times, the legislature has continued to fund and support the state’s SBIR program.

Back on the Farm

All that support is crucial to a really small firm like Hawaii Fish Co. Despite the challenges associated with managing SBIR research projects – not to mention running a fish farm – Weidenbach remains confident about the commercialization prospects for his projects, particularly the alternative-energy aeration system.

“The energy costs associated with aeration can be quite significant,” he says. “Catfish farms can use 10 to 20 horsepower per acre. Shrimp farms use even more. In ballpark terms, a horsepower is about a kilowatt. So, if you run continuous aeration on a 10-acre farm, that’s at least 100 kilowatts an hour. That’s $30 an hour just for aeration; and if you’re running it 24 hours a day, it can be a pretty significant electric bill.” After an initial investment, solar or wind would be free.

That’s why Weidenbach is confident he can sell his technology when he’s done. For now, though, his aeration system remains a half-built prototype, an assemblage of angle-iron and ingenuity heaved up on the edge of the fishpond in Haleiwa. It’s a good idea, but Weidenbach knows better than anybody, it’s going to take more than a little SBIR money to make this project pay.

Hawaii’s Most Successful SBIR Companies, 1982-2010

SBIR awards come in three phases:

Phase I

Beginning this year, Phase I awardees receive up to $150,000 for a six- to nine-month feasibility study of their innovation.

Phase II

Only companies that have successfully completed Phase I are eligible to apply for Phase II, up to $1.5 million for a two-year project to build a prototype or demonstration project.

Phase III

Phase III, which is typically not funded by the government, is commercialization.

SBIR/STTR Resources

One-stop-shopping for all things SBIR and STTR. Visitors to this website can find everything from the latest agency solicitations to abstracts of past awards. Great for general information, too.

Hawaii Technology Development Corp. is the official administrator of the state’s SBIR program. In addition to providing matching funds to federal Phase I awardees, HTDC offers workshops and seminars on subjects such as proposal writing and product development. Through its Manufacturing Extension Program (MEP), companies can get advice on prototype development and almost anything else that has to do with manufacturing.

Because it’s the largest SBIR agency, the Department of Defense has a lot of useful information on its website. Of particular interest is the SITIS section (SBIR/STTR Interactive Topic Information System), which provides technical clarification on solicitation topics.

www.nifa.usda.gov/funding/rfas/sbir_rfa.html

Though not pithy, the website for the National Institute of Food and Agriculture is a quick entry-point to the byzantine world of the USDA’s SBIR areas of interest.