What Makes Waikīkī Dangerous and Who’s to Blame?

Oʻahu's tourism and entertainment hub endures an epidemic of beach thefts, random spikes in violent crimes and an understaffed police force. Here’s what’s being done to counter the crime.

June Goodwin, 69, has strolled along Waikīkī Beach many times during her frequent visits to Oʻahu as the companion caregiver to another Canadian woman who is elderly.

One Friday evening in March 2017 started like so many others: Goodwin finished work, had an early dinner at her regular hangout, Cheeseburger in Paradise, and then walked along Waikīkī Beach toward Kapiʻolani Park.

She usually brings just a beach towel and some cash in her tote, but since she was flying home to British Columbia the next morning, her bag was packed with carry-on essentials, plus her wallet, passport and cellphone.

She watched the sunset and kept walking. Out of nowhere, someone hit her, so hard that her left cheekbone and eye socket were broken.

“I’m not 100 percent sure where it all happened, I just know I was hit from behind and then my face was on the ground,” she says. “Then somebody helped me up. I wasn’t even sure where I was – and I know that area. I asked them where the Waikiki Banyan was (where I was staying) and they pointed me in the right direction and when I got back to the Banyan I realized I didn’t have my bag.”

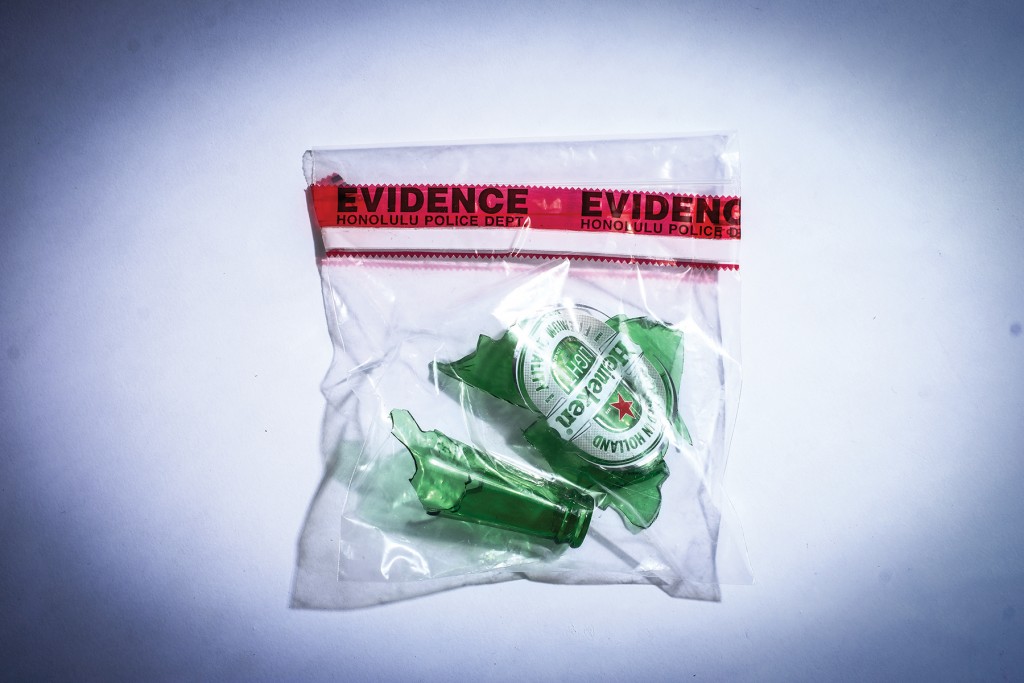

Theft of personal property is by far the most frequent crime in Waikiki, but violent crime also happens all too often. There have been 1,007 reports of larceny this year through early July, according to the Honolulu Police Department. In all of 2017, there were 2,780 reports, up from 2,475 in 2016.

“The numbers (for crime in Waikīkī) have been steady. … Throughout the years you see spikes here and there,” says HPD Deputy Chief John McCarthy, who once served as Waikiki district commander. Last year was one of those spike years: Five people were murdered in Waikīkī, compared with three in the previous two years combined. So far this year, there have been none.

Violent crimes have put Oʻahu’s tourism hub on edge and prompted a conference in February during which more than 200 Waikīkī stakeholders, including law enforcement, tourism officials, businesses, the military and lawmakers discussed how to reduce crime.

It is hard to quantify, but thieves today seem more brazen and homeless people more aggressive. In March, a homeless man put a woman in a chokehold and tried to cut her with a box-cutter. That same month a 25-year-old military man from New York was stabbed above the pelvis on Nohonani Street in the early morning. In July, a woman seven months pregnant had her purse stolen at the Waikiki Aquarium and a female tourist from Arizona was hit in the face by a homeless man. An understaffed police force struggles to cope while Waikīkī seems less and less like the paradise on earth its visitors dream of.

Around-the-Clock Thefts

Cases like the attack on Goodwin are why the Visitor Aloha Society of Hawaii was formed in 1995. VASH helps 1,600 to 2,000 visitors each year – 75 percent are the victims of crime and most of those crimes occur in Waikīkī. “The most common crime we see against our visitors are thefts on the beach,” says VASH President Jessica Lani Rich. “The second is car break-ins.”

Many thefts are crimes of opportunity – people stealing unattended items – but Rich says VASH also aids victims of violence. Rich says VASH assisted the Arizona and New York tourists who were attacked this year; their cases are two of dozens of violent examples. She rattles off others: In 2017, VASH assisted a Canadian woman who had been stabbed with a nail file while waiting at a crosswalk with her husband and young daughter at Kūhiō Avenue and Kanekapolei Street. A woman visiting from the Mainland for a friend’s wedding was severely beaten in Waikiki and unable to attend the ceremony. A couple had their rental car stolen, leaving them stranded and without their luggage.

VASH worked with Goodwin for nearly a week, putting her up at the Ohana Waikiki East by Outrigger, paid for taxi fare to the police station and to the Australian Consulate, which provides passport services to Canadians in Hawaiʻi, and even offered to get her counseling. “VASH was phenomenal,” says Goodwin. “Between them and the front desk at the hotel, I don’t think I would have pulled through without flipping out.”

Rich says the nonprofit encourages victims to file police reports, but most never recover their possessions and thieves are rarely arrested. More than a year later, Goodwin doesn’t know who attacked her and stole her bag – HPD hasn’t arrested anyone or recovered her property.

“I think for the most part, Waikiki is like any other tourist destination,” says Rich, adding that visitors will be safe if they take steps to protect themselves, such as not going out alone at night. “For the most part, Hawaiʻi is a safe destination, but we do have these incidents.”

Jerry Dolak says beach thefts are the most common crime; he blames homeless people and local career criminals. Dolak is the director of security and safety at Outrigger Resorts and president of the Hawaii Hotel Visitor Industry Security Association. The association comprises 75 security managers of hotels, condos, Waikīkī businesses, the Hawaii Convention Center and law enforcement who meet monthly to share criminal intelligence and run a website where they share information as incidents happen.

“The big concern is that we don’t want to push the problem from one property to another. It takes everybody working together to trespass people and make it uncomfortable to commit these crimes in Waikīkī. We want to make them realize that they’re not going to just get away with stuff over and over again,” he says.

“The ongoing homeless situation exacerbates some of the criminal activity we’re seeing here, especially the homeless that are chronically homeless, or dependent on drugs,” adds Mufi Hannemann, president of the Hawaii Lodging and Tourism Association and a former Honolulu mayor. The association’s office is in the Waikiki Business Plaza on Kalākaua Avenue and Hannemann says it’s common to see homeless people outside businesses, on park benches, even harassing visitors.

The problem led City Councilman Trevor Ozawa, whose district includes Waikiki, to introduce a bill this year to remove pavilions along Waikīkī Beach, which he says have become breeding grounds for drug use, sex and fighting, and a hangout for chronically homeless people. Nearby lifeguards often intervene when the police aren’t there, Ozawa says.

“They seem to be a breeding ground for illicit activity. I know that a lot of tourists would like to sit down in a shady place and take a load off. But even if they want to sit down, they cannot because it’s uncomfortable and there’s somewhat of an intimidating presence in that area,” he says. His hope is that if the pavilions are removed, the homeless would relocate and crime would decrease.

The increase in homelessness has hurt business for Bill Comerford. He’s the owner of four bars, including Kelley O’Neil’s and the Irish Rose Saloon in Waikīkī. He says homeless people loiter outside his bars, especially at night. “My business was in a typical growth pattern of 10 percent to 15 percent annually,” says Comerford. “But over the past four years, we’ve stagnated at all four of my locations, primarily because of homelessness. People will not go out at night. It’s not safe.”

Youth-related crime and violence are also on the rise. In 2017, there were three high-profile cases in which teens ages 15 to 18 were arrested: for a shooting death, a stabbing death and an assault with a baseball bat.

Waikīkī appeals to many teenagers, says Deborah Spencer-Chun, president and CEO of the nonprofit, Adult Friends for Youth. “We’ve found that Waikīkī is almost like a playground. Kids can go there, they can get what they want from the tourists and they can cause whatever havoc,” she says. “A lot of these kids don’t have any money, they’re coming from low socioeconomic status and so they’re going to go get what they need and the tourists and military have unfortunately been targets for them.”

Adult Friends for Youth works with violent at-risk youths ages 14 to 17 and their peers through neighborhood outreach and long-term counseling. The success of the program, says Spencer-Chun, comes from not only working with troubled teens, but also their friends, parents and schools. The organization serves 300 to 500 youths each week, devoting three to four years to each.

Spencer-Chun says the youths catch TheBus to Waikīkī from their home neighborhoods, such as Kalihi, Waipahu, Kapolei and Wahiawa, often in the evenings and on weekends. This year, the nonprofit began working directly in Waikīkī; on Fridays and Saturdays from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., staff visit known teen hot spots to conduct outreach. “The goal is counsel the kids, get an assessment and take the kids home and work with them in their communities.”

HPD Understaffed

Susan Ballard became HPD’s chief of police in November, in the thick of Waikīkī’s spike in violent crimes, and inherited a department that, among other issues, currently has 279 officer vacancies. Ballard says the department is working to fill those vacancies, which built up over many years.

“When Chief Ballard took over as chief, we were looking at some patrol districts only running at half their strength,” says McCarthy. He says HPD now has a policy that patrol districts must be staffed at 75 percent. The goal is to increase the number of officers by 5 percent each year until the department is fully staffed. “Right now we’re paying overtime in the event that the patrol district cannot meet 75 percent – we’re able to call in officers through overtime to work.”

The Waikīkī district doesn’t have the numbers to always station officers at known problem areas, like the Kalākaua Avenue pavilions where homeless people congregate or along Lewers Street where certain bars with cabaret licenses close at 4 a.m. “We’re there sometimes, we’re not there at other times because we’re at other calls or cases.”

McCarthy says 100 to 115 officers are assigned to the Waikīkī district. At any given time at least nine beat officers are on duty – more work at night – not including the district’s crime reduction and support units and foot patrols. After HPD recruits graduate, they temporarily patrol either Waikīkī or Chinatown on foot; McCarthy says between 20 and 25 officers patrol Waikīkī on foot now, but adds that will likely be cut in half because the next graduating class is smaller than the latest one.

“Staffing is the critical issue. People want to see police walking the beat, they want to see police driving around,” he says. “We’re working on plans to increase the foot patrols in both Waikīkī and Chinatown and downtown for a more consistent period of time.”

Security firms across the island face similar staffing challenges, adds Dolak. “The low unemployment makes it harder to hire security officers. Security officers are not the highest paid … so it’s getting harder and harder to keep the security staff manned at its full potential,” he says. Dolak says he doesn’t think security turnover has directly contributed to crime in Waikīkī. “Not yet, as long as we keep the positions filled, but if it continues like this it can be a potential problem if we can’t fill them.”

Fueled by Alcohol

Friday and Saturday nights are especially busy for HPD officers in Waikīkī. As it gets later in the night, more service calls are alcohol related, says McCarthy. “For a lot of violent crime incidents, if you’re going to trace it back, alcohol is often a factor,” he says.

Thefts of opportunity most frequently happen during daylight when tourists are plentiful, he adds. In the late night and early morning hours, darkness coupled with fewer witnesses increases the chances for thieves to become threatening, and for violent crimes to occur. In March 2018, a 25-year-old visiting military member was stabbed and seriously injured. In October 2017, a 21-year-old Schofield Barracks soldier was beaten with a baseball bat and stabbed and a 23-year-old Kāne‘ohe-based Marine was fatally stabbed. All three crimes occurred late at night.

In December, the Armed Forces Disciplinary Control Board released a notice about crime and violence in Waikīkī to inform service members of high-risk areas. The areas include cabaret licensed bars; six Waikīkī establishments hold cabaret liquor licenses. Tom Burke, deputy director of emergency services for U.S. Army Garrison-Hawaii, says in an email that the board wants service members to be wary but is not considering barring them from Waikīkī.

During the Visitor Public Safety conference in February, law enforcement officials suggested limiting 4 a.m. cabaret liquor licenses. They contended that closing all bars at the standard 2 a.m. closing time would reduce fights and other violent crime after the bars close. Service members have been involved as both perpetrators and victims.

Cabaret license holders like Comerford disagree. He says whether bars close at 2 a.m. or 4 a.m., homeless people are still there, fights can still happen and visitors, residents and service members can still be attacked. As of press time, no legislation has been introduced to restructure cabaret liquor licenses.

Directly outside of Comerford’s Lewers Street bar is often the scene of early morning, drunken fights between service members or between them and residents. McCarthy says the police know it’s a problem and try to be there. “In the 1970s when I was first a policeman, we used to (be there when the bars close). We always try to do that; that’s when the problems break out,” he says. “However, we don’t always have enough personnel to do that now.”

It wasn’t 4 a.m. when Goodwin was attacked, and she wasn’t intoxicated. “As far as I can figure, the worst thing I ever did was I traveled (Waikīkī) beach with my bag,” she says.

When Goodwin arrived home in Canada, her face was still bruised, but she had to replace her driver’s license. Now, every time she has to show her ID for the next five years, it’s a bitter reminder of what happened to her on the March evening. While she had to get a new driver’s license, she says, she held off on renewing her passport. “I’m just not quite ready. I travel by myself and I just wasn’t quite ready to make that adventure this year. But I would say I’ll be back (to Oʻahu) next year.”