Why big development is so difficult in Hawaii

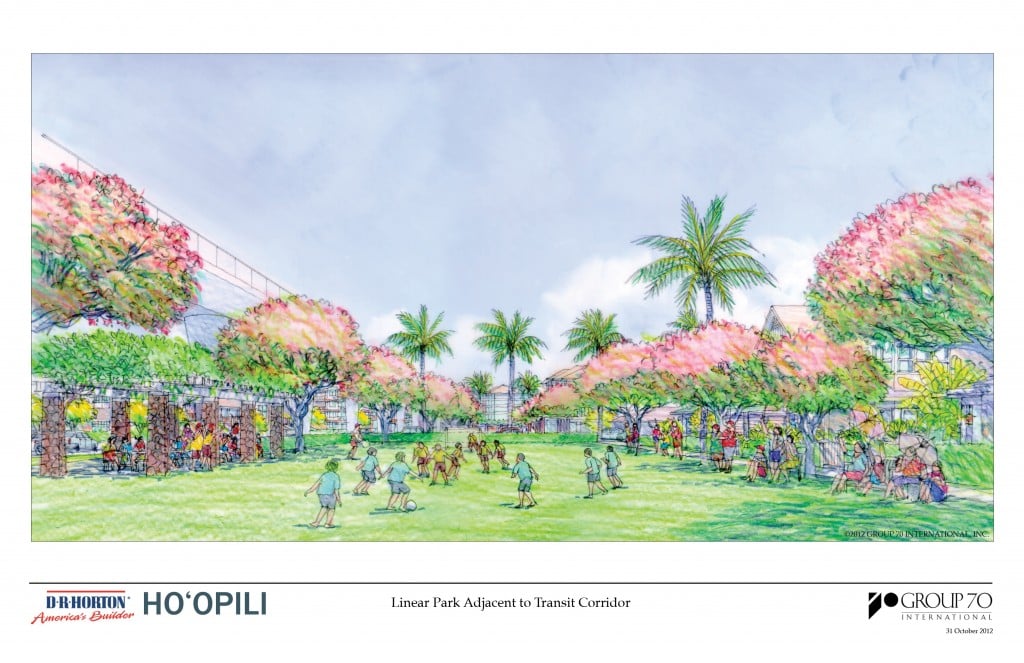

Photo: Courtesy of Hoopili

For decades, “too difficult” has been the refrain in the development community. Developers believe Hawaii’s land-use laws are too complicated, environmental regulations too onerous, and deference to Native Hawaiian gathering and access rights misguided and even unconstitutional. The consequence is a long list of major development projects that have either failed or get enmeshed in tortuous, sometimes decades-long litigation: Queen’s Beach, Turtle Bay, Koa Ridge, Hoopili and, if you are thinking broadly, the Superferry.

That’s how developers explain it. The truth, though, is more complicated and if there is any chance to improve the system, it helps to understand the nuances.

According to David Callies, the Benjamin A. Kudo professor of law at University of Hawaii and author of “Regulating Paradise: Land Use Controls in Hawaii,” our land-use laws are “the most restrictive and complex in the country.” One of the main reasons, he says, is because Hawaii is the only state that has a statewide body responsible for regulating land use, the Land Use Commission.

By email from his sabbatical in Australia, Callies writes: “The Hawaii system is more complicated because of its many layers, particularly at the state level, with the Land Use Commission boundary-amendment process to change the state land classification from agriculture to urban.” This reclassification process is critical, he points out, because nearly 95 percent of the land in Hawaii is currently designated either conservation or agriculture, neither of which permits major developments. And getting the LUC to reclassify land isn’t simple. It can require public hearings, detailed plans and a lot of time. Maybe more important, LUC hearings are “quasi-judicial” proceedings. That means the opponents of a development have an opportunity to testify, provide their own expert witnesses and cross-examine the witnesses for the developer. Consequently, disputed cases can be laborious affairs.

The LUC isn’t the only layer of land regulation. The developer also needs numerous permits and approvals from the counties, which are responsible for zoning within the urban district, issuing

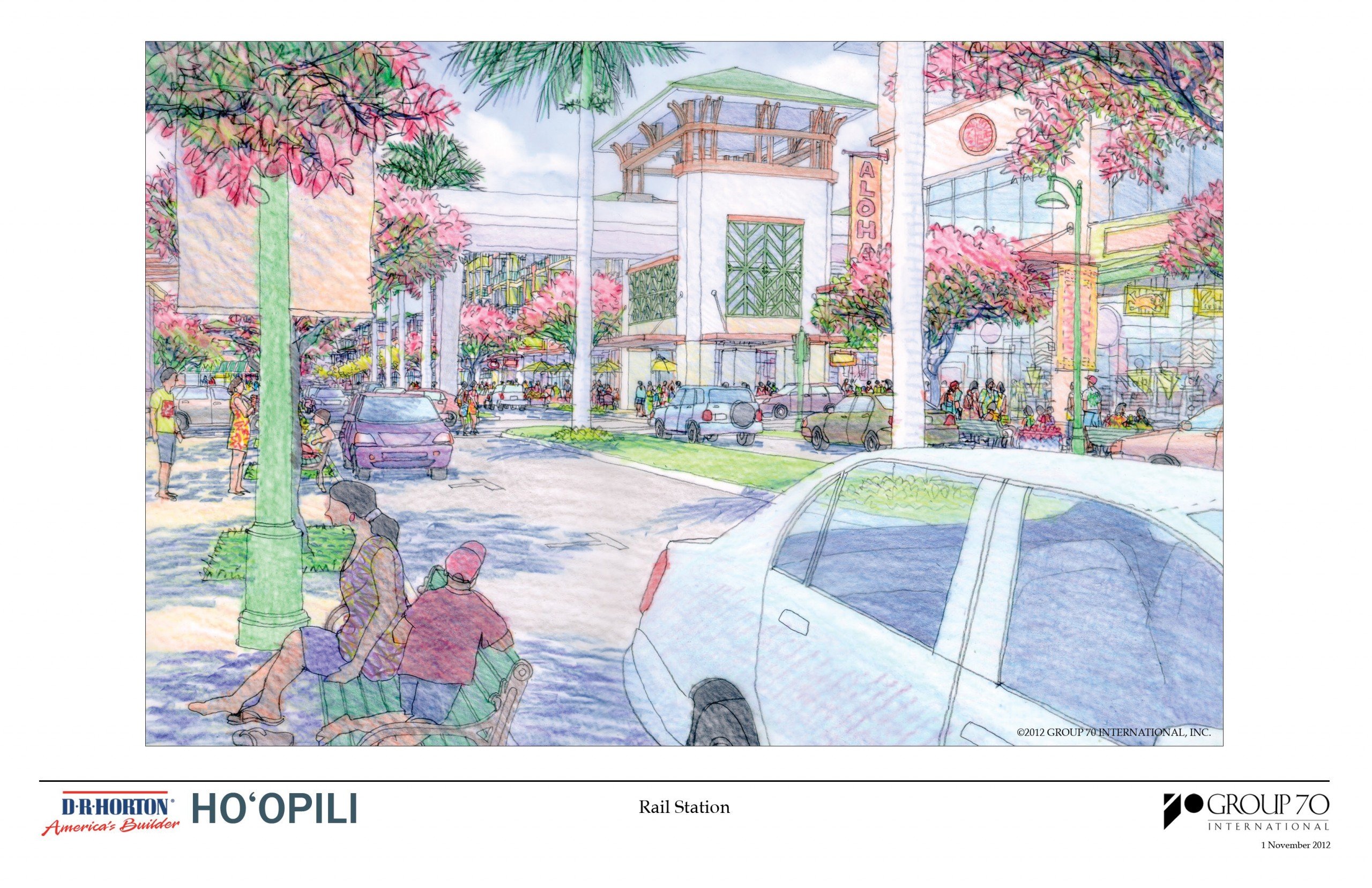

Photo: Courtesy of Koa Ridge

building permits, preparing and revising the county development plans, etc. Developers must also contend with a host of state environmental regulations, many of them based on federal law. For example, HRS 343, which deals with environmental impact statements, says any project that involves state land or state money may require an environmental review. Also, under the Coastal Zone Management Act, a federal law passed in 1972, the entire state is considered a “coastal zone management area,” which means developers have to consider the effect their project will have on the coastal area. Within the CMZA, the state has designated the most critical portion, essentially the area between the shoreline and the first highway, as a Special Management Area, or SMA, which requires its own permitting from the county. Hawaii developers also must conform to the federal Endangered Species Act, which can be especially burdensome in the state that is considered the endangered species capital of the world. Under the ESA, for example, the entire islands of Maui and Hawaii are considered “critical habitat.”

Photo: Courtesy of Koa Ridge

Navigating all those hoops takes a lot of time, Callies points out. “The LUC process takes at least two years,” he says. “And the county zoning at least another year, usually two or three. And then there are coastal zone permits, preliminary and final subdivision approvals, and a host of environmental permits. That’s 10 years at least, altogether.”

One way to speed up the process would be to get rid of the LUC and leave land-use regulation to the counties, as other states do. That’s what Callies advocates. Others disagree.

Contrary View

Robert Harris, executive director of the Hawaii Chapter of the Sierra Club (and, like many land-use attorneys here, a former student of Callies), believes the LUC serves a critical role. “The Land Use Commission,” he says, “is supposed to be responsible for the long-term planning, such as looking at how to advance and preserve agriculture, water conservation, energy usage and growth plans. It’s relatively clear that most of the counties don’t engage in that level of planning.” Moreover, he says, county procedures are ministerial rather than discretionary, meaning they don’t allow for that crucial quasi-judicial review.

Callies has a different take. “The original intent of the Land Use law,” he says, “was, first, to preserve large areas of agricultural land for plantation use, and second, to prevent sprawl. A distant third was concern for the lack of staff and expertise on the Neighbor Islands. The first and third are no longer relevant. We have no plantation agriculture requiring vast swathes of ag lands, and all four counties have more than adequate staff in their respective planning departments.” In other words, get rid of the LUC.

Litigation

Not everyone believes that land use regulations are the problem. “When you speak to real developers,” Harris says, “the regulatory side is not where their source of frustration lies, and they’ll tell you that similar regulations occur in almost every state. What developers like is for those regulations to be efficient, to move in an orderly process, and they like to have finality when it gets decided. But it isn’t the regulatory process that daunts them. It’s the cost of financing a project out over time, the cost of construction and construction delay. Those are the things that really drive them to distraction.” While developers may say the biggest delays are caused by lawsuits filed by organizations such as the Sierra Club and the Native Hawaiian Legal Corp., environmental and Native Hawaiian rights advocates contend they’re just making sure the process is followed.

Denise Antolini, an associate dean at the UH law school and a prominent environmental attorney, believes the current system works well for those who play by the rules. “I think there is a lot of development moving ahead successfully in Hawaii – some of it very good,” she says. “The rules are pretty clear on most land-use and environmental laws, and I think the businesses and developers who are used to operating here know how to get through the system. I think the projects that get stymied, or become controversial, or blow up, tend to be the projects driven by interests that don’t have a lot of experience or roots in Hawaii.”

Antolini’s contention is that most of the major land-use litigation over the past decade has been for projects developed by off-island corporations. Callies has a different take: He thinks only off-island interests – those who only expect to do only one project in Hawaii – can afford to challenge the system. Local developers, who know they have to deal with the LUC and the counties in the future, are afraid to rock the boat.

Bill Meheula, a prominent land-use litigator, takes a kind of middle ground. “Litigation, if its purpose is to bring the developer into compliance with the law, is perfectly valid,” he says. “I think that most developers here go to great lengths to comply with the law because they don’t want litigation to stop or delay their projects. But what’s happened all too often is that some plaintiffs are filing lawsuits not because there’s a legitimate basis to find the developer not in compliance, but just in order to stop or delay the project long enough that it’s not going to be profitable.”

Meheula also suggests a cure: “My recommendation would be that any state law or county ordinance that sets forth requirements that a developer has to comply with should have a provision that says, ‘If anyone sues for violation of these laws, then the prevailing party should be entitled to attorney’s fees.’ ” Meheula contends this will have two consequences: discourage frivolous lawsuits and attract highly qualified attorneys to legitimate cases because of the prospect of attorney’s fees.

Most environmental attorneys don’t agree that frivolous lawsuits are a problem. “Certainly, the well-established citizens’ groups and the well-established attorneys who work on these issues don’t bring frivolous cases,” Antolini says. “They wouldn’t survive, and they’re in it for the long term.” She sees the issue mostly as a matter of “framing.” “From the community’s perspective,” she says, “some of the cases that are brought to court may seem like legal long shots, but they’re often test cases where the law is unsettled. And the stakes are so high that, on balance, it’s worth pushing to find out what the law or the courts will support.”

In some ways, the whole dispute over excessive litigation is about “framing.” Property-rights advocates, like Callies, look at the long list of projects stopped by litigation and say: “The process has been co-opted by NGOs like the Sierra Club and the Native Hawaiian Legal Corp.” Environmental advocates, like Harris, point out that “thousands and thousands” of development projects go on unchallenged every year. “Looking at those projects,” he says, “there’s probably, at best, a couple of environmental litigation cases that come out each year.” Moreover, he says, the members of the LUC “are almost entirely representatives of the development community or the large landowners, so there’s a question whether they’re being fair, impartial and objective on a consistent basis.”

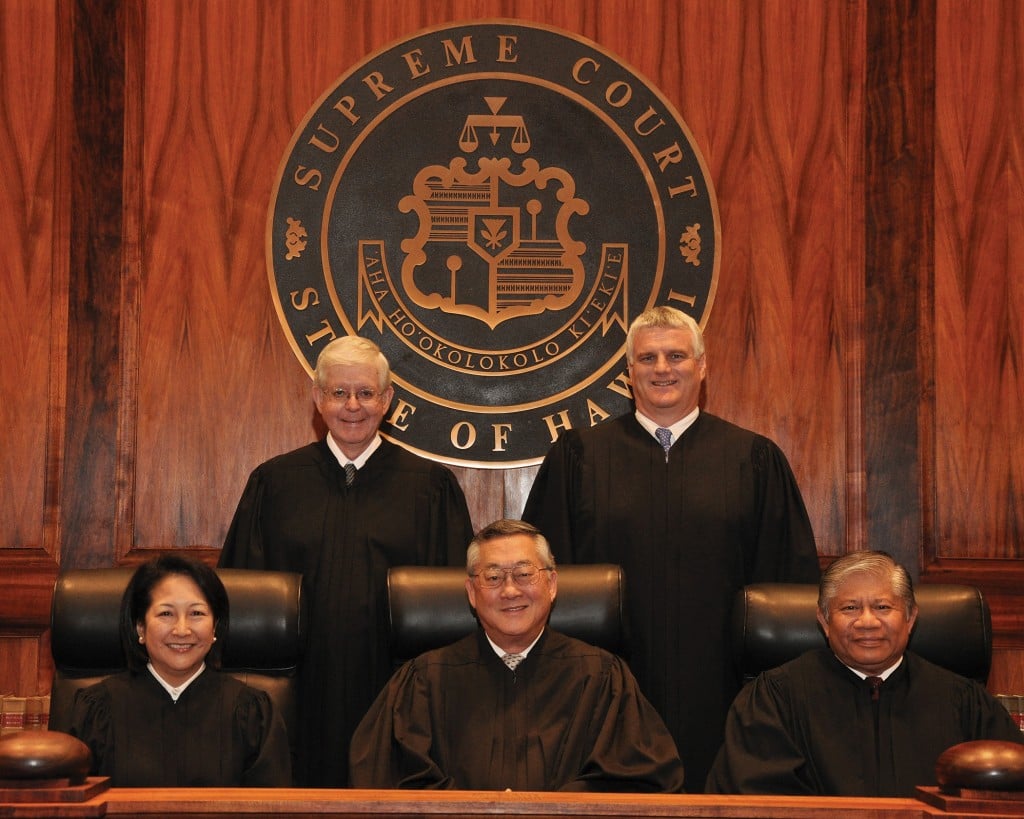

Photo: Courtesy of the Hawaii Supreme Court

High Court

Of course, when Harris talks about thousands of development projects going unchallenged, he’s talking mostly about many small projects and a number of big projects involving redevelopment of already-developed land. The contentious cases tend to involve big projects on land that is agricultural or conservation. Those are the cases that the development community has often lost at the state Supreme Court.

In the summer of 2011, Callies wrote a paper for the Hawaii Law Review that criticized the land-use record of the state Supreme Court under the leadership of Chief Justice Ronald Moon. One of his primary criticisms was that the Moon Court was biased toward activists groups such as the Sierra Club, Earthjustice, Hawaii’s Thousand Friends and the Native Hawaiian Legal Corp. By Callies’ calculation, the high court sided with anti-development groups 82 percent of the time, reversing the more pro-development Intermediate Court of Appeals 65 percent of the time.

While no one disputes Callies’ numbers, other members of the legal community are less than impressed by their significance. Robert Harris, for example, reminds us that nonprofits like the Sierra Club have limited resources and can’t afford to fight every battle. “We tend to take on the most obvious, worst-case examples,” he says. “Broadly speaking, Callies’ complaint is that we win too often, when the reality is that we select those cases that are the worst examples of abuse, so it’s not terribly surprising that we tend to win.”

Callies seems particularly disturbed by the court’s ruling in the Turtle Bay decision. In that case, the developer’s original EIS was accepted in 1985, but, for several reasons, the developer waited until 2005 to file for a subdivision approval. The Supreme Court, once again reversing the Intermediate Court of Appeals, ruled that the developer would have to file a Supplemental EIS. According to Callies, adding a time limit to an EIS “appears nowhere in the statute.” Like several of his specific complaints about the Moon Court, this one is debatable. For example, the wording of the law seems pretty clear about the limitations of an original EIS (at least to a layman): “A statement … is usually limited by the size, scope, location, intensity, use and timing of the action, among other things.” (Italics added.) Twenty years delay seems like a significant change in timing.

But Callies’ broader argument – that the Turtle Bay ruling and other Moon Court decisions reflect a conflict with traditionally accepted concepts of property rights – is harder to dispute. As Callies puts it: “The use of private land is not a privilege but a right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.”

In the same issue of the Hawaii Law Review in which Callies’ paper appeared, Denise Antolini published a counter-argument. Her main contention was that the Moon Court wasn’t so much focused on environmental issues as it was on process – making sure developers and agencies follow the letter and intent of the law. She points to the first section of Chapter 343, the statute governing environmental impact statements, which says environmental review is an important part of the planning process and that “public participation during the review process benefits all parties involved and society as a whole.” Many of the Moon Court’s rulings can be seen as simply enforcing that basic principle.

Antolini writes that the Moon Court rulings were grounded in “the four key principles of the state environmental review system”: protecting the environment, serving an “informational role,” ensuring public participation and improving the quality of agency decision-making. As she puts it, the Supreme Court “has made it clear that agencies and developers proceed at their peril if they circumvent the environmental review process.” In case after case, that’s what developers and agencies appear to have tried to do. For example, no matter how much we may lament the loss of the Superferry, it seems clear the state tried to sidestep a required EIS. And the Turtle Bay developers made a valiant attempt to avoid a Supplemental EIS. In both cases, the Moon Court made them pay.

Photo: Mike Keany

Bottleneck

There are other key players in this drama: the regulators. A lot of the delay and confusion over land use in Hawaii can be traced right back to the agencies responsible for regulating the process. Environmentalists and Native Hawaiian advocates often accuse them of being too cozy with developers. Developers, on the other hand, criticize them for being slow and inefficient. The agencies’ leaders, though, are of mixed minds.

David Tanoue, former director of the Department of Planning and Permitting for the City and County of Honolulu, tends to agree with Callies that the main problem with our land use system is the court. But he adds that the regulatory process is often slow for a reason. “We need checks and balances,” he says. “At the department, I stressed that we’re not looking at the merits of the project. We’re looking at how the process and procedures are followed. Because that procedure can be used as a sort of a shield. Following procedure may be too slow for some private developers’ time frame, but that’s what’s going to protect them if their case gets challenged. And if we deny an application, and the developer sues the city, we can say, ‘We followed the procedures, and the project didn’t meet all the criteria, so we denied it.’ Likewise, if we approve a project, and we get challenged, we can fall back on procedures.”

The glacial pace of permitting can also be attributed to a lack of resources. This isn’t just at the counties, which handle the bulk of the permitting process; it’s also true at the state level. Jesse Souki, director of the state Office of Planning, points out that his office’s budget fell steadily through the previous three administrations. “We had about 80 generally funded planners under (Gov. John) Waihee. Today, we have about 12 generally funded planners. And the budget follows the same arc.”

Souki also notes that there are further costs to this lack of resources. “For example,” he says, “we’ve been asked to do some planning about infrastructure. Well, we would do that if we had the money for it. Also, this office hasn’t done a five-year boundary review since the early 1990s. Of course, we’re supposed to do it every five years. The boundary review is supposed to evaluate where the current state land use districts are, where the county growth boundaries are, and then takes the initiative to get that land redistricted, instead of a case-by-case planning effort.” Given the absence of thoughtful, comprehensive review, maybe it’s not surprising so much conflict revolves around individual boundary amendments.

One person with a different perspective is George Atta, the new (and former) director of the Department of Planning and Permitting for the City and County of Honolulu and former partner at the planning, design and architecture firm Group 70. “This is just my personal opinion,” Atta says, “but just as public discourse at the political level has become antagonistic, individuals increasingly seem to have polarized views from one another. They don’t look at one another as neighbors anymore. Their neighbors have become antagonists or opponents. That’s not a legal problem; that’s more of a social or cultural thing that’s been slowly growing.”

Photo: Thinkstock

Working as intended?

There’s another way to look at this. Maybe our regulatory system is working just as it was designed to work. Instead of complaining about our complicated land-use laws, or overzealous environmentalists, or policy-making by the state Supreme Court, we should look inward. These are laws, after all, that were written by elected officials: state legislators, county councilors and constitutional convention delegates. If we don’t like the laws anymore, we can elect officials to change them.

The laws’ main obstacle to development may not be that they’re too restrictive, it may be that they’re too democratic. Callies complains that the Moon Court vastly extended the concept of ‘standing,’ which defines who can bring a case to court. Extensive public participation and access to information is hard to revoke, especially in an arena as contentious as land use. As Jesse Souki puts it, “In land-use processes, the public just has to be involved. There may not be a constitutional provision that says that, but if you’re going to have a state or county permitting process that doesn’t involve the community or public hearings, good luck with that.”