Hawaii’s Rural Hospitals on Life Support

Here’s how Hawaii’s rural hospitals (barely) stay afloat. For some, things have gotten better, but others face an even more difficult future.

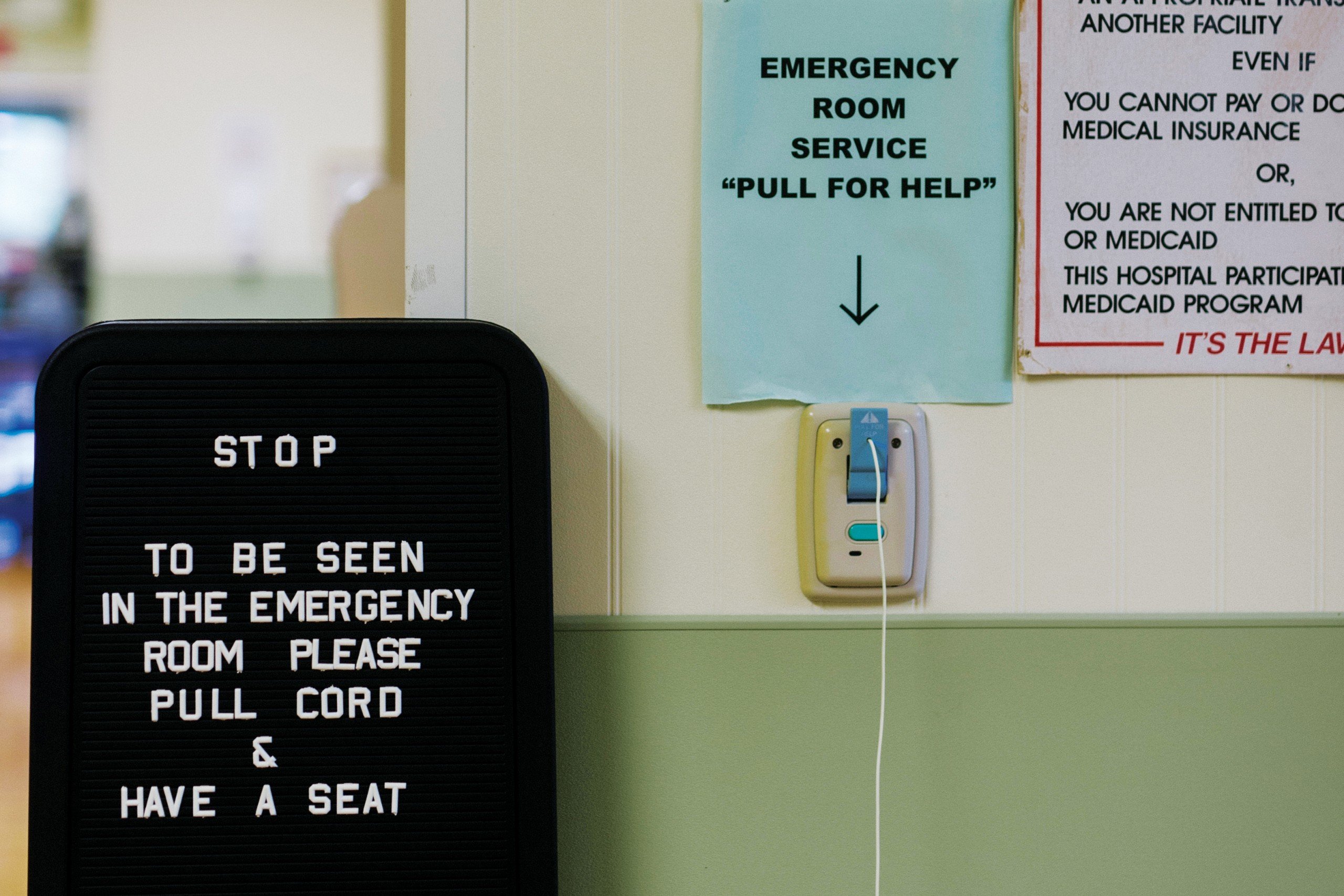

State Sen. Josh Green works the weekend shift at Kohala Hospital’s emergency room, and it’s normally quiet. That could change in seconds. A car crash. A heart attack. A man enters the emergency room with a saw in his arm. A woman comes in with a shattered and dislocated ankle.

If Green hadn’t been there to put the woman’s ankle back in place, the circulation to her foot would have been cut off, and amputation would have been necessary. “My service saved her foot,” he says, “but I couldn’t do the surgery. Two hours later, I got her to North Hawaii Community Hospital where they put a bigger splint on and they did the operation the next morning. Six weeks later, she’s more or less fine. Three months later, she’ll forget altogether that she ever had it. But she would have lost her foot without the critical access hospital. And I’ve seen that story over and over again.”

He adds: “It’s not every day, but if we turned our backs on the critical access hospitals, some people would have really terrible outcomes.”

Hawaii has 14 rural hospitals. They serve communities like Kohala and Kau on Hawaii Island and Kapaa and Waimea on Kauai. In many cases, each is the only access point to emergency care in their community. Nine of these hospitals have the designation “critical access hospital” that provides enhanced federal funding — to care for certain Medicare and Medicaid patients — that helps them stay open.

Regardless if a hospital has this designation, the challenge is that health-care organizations are dependent on lots of patients — which rural hospitals don’t have, so they can’t financially sustain themselves. In addition, the costs of health care continue to increase, and the hospitals’ state, federal and commercial funders aren’t keeping up. This environment makes it hard for a rural hospital to feel financially secure, says Linda Rosen, CEO of Hawaii Health Systems Corp., the state’s public hospital system of 10 facilities and two affiliates.

Eight of the state’s rural hospitals are part of HHSC; six others are privately owned. Nine small, rural hospitals have the critical access designation, given by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This designation, Rosen says, was designed to provide a better operating environment for these hospitals. Each of the state’s critical access hospitals treats fewer than 7,000 patients overall in their emergency rooms each year — not just patients insured by Medicaid and Medicare. “Having a sparse population in a given area means that the hospital has to spread its costs over a smaller number of patients than a bigger hospital,” she says.

When Sen. Josh Green is not at the state Legislature, he works as an emergency room physician at Kohala Hospital. He says critical access hospitals are needed to provide emergency care in their communities.

Here’s how rural hospitals get paid and why it’s not as much as they need

The nine critical access hospitals receive cost-based reimbursements from the federal government for care provided to Medicaid inpatients and outpatients — Medicaid will also reimburse critical access hospitals for some other services, though these payments are not based on a hospital’s costs — and Medicare inpatients, outpatients and skilled nursing patients. Hospitals without the critical access designation are reimbursed by an amount set for each procedure or service that’s performed and adjusted by the complexity of the case, says R. Scott Daniels, coordinator for Hawaii’s Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Program.

patients. Hospitals without the critical access designation are reimbursed by an amount set for each procedure or service that’s performed and adjusted by the complexity of the case, says R. Scott Daniels, coordinator for Hawaii’s Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Program.

While this does give critical access hospitals a financial advantage, these reimbursements don’t always cover a hospital’s total costs. Critical access hospitals don’t get cost-based reimbursements from Medicaid and Medicare to cover the costs of caring for privately insured patients or if a bed is vacant, says Wesley Lo, who used to be CEO of HHSC’s Maui region, which included Lanai Community Hospital, Kula Hospital and Maui Memorial Medical Center. The three hospitals are now under Kaiser Permanente’s ownership as the Maui Health System.

On Kauai, the critical access designation is “a lifesaver for a small hospital and without it, we probably would be in a … much more serious financial situation,” says Peter Klune, CEO of HHSC’s Kauai region, which includes Kauai Veterans Memorial Hospital and Samuel Mahelona Memorial Hospital.

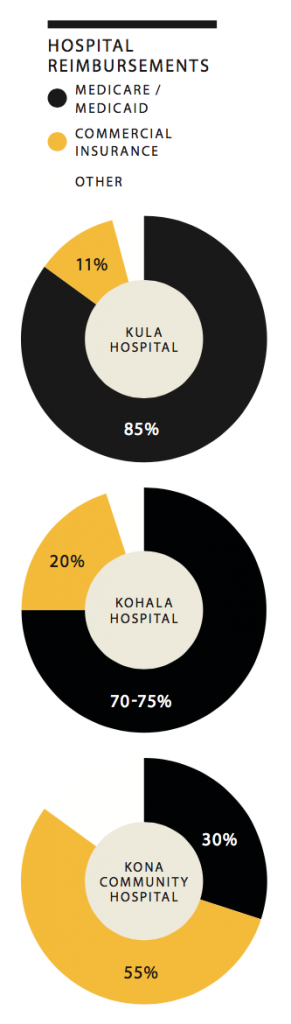

Hospitals are also reimbursed by their commercial insurers. The amounts hospitals receive are based on the services provided and adjusted by the complexity of each case, Daniels says. The issue for rural hospitals, Rosen adds, is they have few patients covered by commercial insurance companies such as HMSA. At Kohala Hospital, about 20 percent of revenues come from commercial insurance reimbursements, compared to 70 to 75 percent from Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements. At Kula Hospital, 11 percent of revenues come from commercial insurance compared to 85 percent from Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements. At Kona Community Hospital, 55 percent of revenues come from commercial insurance, compared to 30 percent from Medicare

and Medicaid.

“Private insurers do not always pay better than Medicare, but it depends on the procedure and how the hospital is able to increase volume. It also depends on the ability of the hospital to increase service lines that do pay higher rates while minimizing the lines that do not pay as well,” Daniels says. “This has resulted in an emphasis of specialty care over primary care as the complex specialty procedures generate more revenue, or at least that is the way it has been. Because critical access hospitals operate more in the primary care end of the health care spectrum, their reimbursements from private insurers tend to be low, to the point that insurers in many cases were reimbursing below cost. This has been a problem in Hawaii in the past, especially for critical access hospitals.”

He adds that the health care environment is changing as private insurers, Medicaid and Medicare are all moving toward paying for value, rather than quantity of services and procedures — where a facility is paid for keeping the patient healthy.

Kahuku Medical Center has about 180 employees and serves about 7,000 patients in its emergency room every year.

Operating a hospital is becoming more expensive, and subsidies are not keeping pace

Federal reimbursements don’t guarantee that critical access hospitals operate above water, Rosen says: “Some can do a little bit better than others, but in general, all of our hospitalsneed our operating subsidy” from the state government. Most of the other rural hospitals also receive yearly state subsidies.

Jay Kreuzer, CEO of HHSC’s West Hawaii region, which includes Kohala Hospital and Kona Community Hospital, says the yearly state subsidies make up about 15 percent of Kona Community Hospital’s revenue, and the amounts the hospital receive each year have been

consistent and appropriate. On the other hand, Gino Amar, administrator for Kohala Hospital, says getting enough state funding has always been a challenge as health-care costs increase, so the hospital always looks for ways to improve efficiency. “Our philosophy here is we try to make ends meet before we might have the subsidy.”

Rosen says the state hospital system can go to the state Legislature for help when its hospitals don’t generate enough revenue. “But it is difficult because … we’re usually requesting just the minimum we need, and so there certainly are times we would like to expand and grow services, but that’s difficult.”

On Oahu’s North Shore, Stephany Vaioleti, former CEO of Kahuku Medical Center, says consistent state subsidies put life back into that rural hospital. The hospital used to operate as a standalone facility and lost money from having too few patients to offset the costs of providing services like same-day surgery and obstetrics. Debt accumulated each year and in 2007, the hospital board filed for bankruptcy. Joining HHSC in 2008 as an affiliate allowed the hospital to receive state subsidies each year, which today make up about 12 percent of the hospital’s revenue.

Despite these state subsidies and assistance from the federal government, rural hospitals are struggling to survive. One reason rural hospitals struggle is that many of the costs over which they have no control are increasing: labor, medicine, supplies and equipment. Eric Shell, a consultant and director with Stroudwater Associates, a health-care consulting firm, says 80 percent of a rural hospital’s operating expenses fall into these fixed costs.

For Hawaii’s public rural hospitals, labor poses a special challenge. At Kohala Hospital, Amar says salaries and benefits make up 70 to 75 percent of the hospital’s operating budget; that figure should be closer to 50 to 55 percent. Daniels says this financial challenge can be attributed to the wage structure for the HHSC hospitals. Hospital staff are considered state employees and participate in the state’s collective bargaining processes.

“If you look at the two critical access hospitals that are the top performing financially, they are independent from the civil service requirements for their workforce,” he says, referring to Kahuku Medical Center, an HHSC affiliate, and Molokai General Hospital, a critical access hospital under The Queen’s Health Systems. Both are exempt from the state’s collective bargaining requirements. According to Vaioleti, Kahuku Medical Center negotiates with its unions on its own and would pay $2 million more per year if its employees were HHSC employees.

“I suspect that when Kula and Lanai (hospitals) become fully transitioned under Kaiser, you’ll start to see … dramatic improvements in their financials,” Daniels says.

While costs go up, reimbursements from government and commercial payors remain flat. That’s the “big elephant in the room,” says Klune of HHSC’s Kauai region. Jen Chahanovich, president and CEO of Wilcox Medical Center in Lihue, adds that the financial impacts of this trend are being felt by all hospitals across the state.

The solutions include partnering with nearby health centers

For hospitals to survive, they need to be able to reinvest in themselves to grow their businesses, Lo says. That’s what Maui Memorial was trying to do before it joined Kaiser Permanente. However, the small hospitals, like Maui Memorial, don’t have enough volume to provide the services — typically specialty services — that can generate the highest revenues.

Rural hospitals can’t do everything. They’re there to provide emergency care and serve as an access point to other health care services. So rural hospitals need to find partners and achieve economies of scale to care for their communities. That may be through partnering with a bigger organization, like the HHSC Maui region did with Kaiser, or through sharing services with community partners, like Federally Qualified Health Centers or even local laundry and kitchen facilities, Lo says. Typically, rural hospitals want to hit economies of scale for purchasing agreements, training programs, and shared staff for things like billing and compliance. “It’s very difficult to be freestanding,” Rosen adds.

In 2012, Sen. Josh Green introduced resolutions at the state Legislature suggesting that the HHSC critical access hospitals look into being designated as Federally Qualified Health Centers — health-care facilities that also receive enhanced reimbursements to cover the costs of caring for Medicare and Medicaid patients. “When you’re dealing with taxpayer monies and subsidies, you should do all that you can to streamline and make efficient the model,” he says.

As an example, he cites Kau Hospital, where he used to work weekends in the emergency room. The hospital and nearby health center were partnered, so the emergency room doctors could assist in the center and vice versa, and this addressed the physician shortage and reduced labor costs. Rosen says HHSC hospitals are already required to collaborate with health centers to maximize reimbursement for the health care services they provide and ensure appropriate care is provided to the communities.

Diana Shaw, executive director of Lanai Community Health Center, says the center has a relationship with Lanai Community Hospital for x-ray, blood draw, emergency room and inpatient services. In addition, the center works with the hospital’s leadership on community education, and each facility tries to not duplicate the other’s services. There can be tension if a health center and nearby rural hospital have duplicate services, such as for primary care.

“In communities where hospitals have started primary care services, the safety net tends to actually get weaker as the organizations compete for patients, staff and other resources,” Shaw says. “This situation can be avoided, of course, with due diligence and careful investigation to ensure that additional primary care services are indeed needed in that particular area, and that a head-to-head competitive situation is not created.”

At the two Kauai critical access hospitals and at Kau Hospital and Rural Clinic, employees wear multiple hats and switch between affiliated clinics and hospitals in their regions. “Those kinds of things have been forced by some of the economics of our industry for us to look for new opportunities to contain costs,” says Dan Brinkman, CEO of HHSC’s East Hawaii region, which includes two critical access hospitals, Hale Hoola Hamakua and Kau Hospital and Rural Clinic.

In addition, Kau Hospital and Hale Ho‘ola Hamakua are supported by Hilo Medical Center for things like purchasing, training and other professional services. “Everybody is interested in working together, especially in the rural areas,” says Kohala Hospital’s Amar.

The nine critical access hospitals also meet every quarter as part of Hawaii’s Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Program to discuss best practices for finances and operations, adds coordinator R. Scott Daniels.

Here’s what a few hospitals have already done to save themselves

There’s another solution: working with a private partner.

Molokai General Hospital, North Hawaii Community Hospital and Wilcox Medical Center have benefited from joining large, private systems. Molokai General Hospital encountered financial difficulties in the mid-1980s, when federal reimbursements were harder to get and hospital requirements were tightened, says Janice Kalanihuia, the hospital’s president. On Hawaii Island, North Hawaii Community Hospital didn’t have the volume to operate alone, says president Cindy Kamikawa. Today, Queen’s supports the two hospitals by providing access to its HR, contracting and legal teams, and sharing staff and services across campuses. Wilcox joined Hawaii Pacific Health in 2001, and like the other two hospitals, it also benefits from the resources and expertise of the system and its sister facilities.

In 2009, Stroudwater Associates found the state hospital system was in a “financially perilous condition.” The consulting firm recommended three changes: achieve operational efficiencies, assess efficiencies of scale within the system model and convert to a private nonprofit corporation. Becoming private could have saved the system up to $80 million a year, mostly because its employees would no longer be state employees. According to Rosen, it’s up to each HHSC region whether to privatize.

For the three former HHSC hospitals on Maui, a private partner was needed because the Maui region did not have the size and money to invest in better services and generate more profits under HHSC, Lo says.

HHSC’s West Hawaii region has had conversations with potential partners, and Jay Kreuzer, the region’s CEO, says the region is interested in doing something similar to what the Maui region did.

“Privatization is needed to provide the services in this community that we need. … There’s still almost 40 percent of the population on this island that goes to Oahu or Maui for their health care, and … a lot of those patients could be cared for here if we had the facilities and the physicians that could provide that care,” he says. “Our goal is to grow our services here. We need a partner to do that.”