Hawaii Beekeeping Makes a Comeback

Lauren Rusert

“My bees were dying. I was crying. I had 40 hives and 36 of them were dead. My friends said, ‘Find a new job. The bee business is done.’ ”

Diminutive Puna beekeeper Jen Rasmussen recounts the devastation she faced in 2010 when two predatory pests rapidly invaded Hawaii Island. She thought her apiary career was finished along with her fledgling company, Paradise Nectar.

Rasmussen was not alone. A survey of beekeepers conducted by the Big Island Beekeepers Association in January 2011 revealed the extent of the damage. Varroa mites, small hive beetle and a third, slower-acting threat, a microscopic fungal parasite called Nosema ceranae, had killed 55 percent of the bees on the island – a total of 2,535 managed colonies – during the previous year, the survey indicated. Fifty-nine beekeepers responded to the survey out of 120 that were asked; 81 percent identified themselves as hobbyists and 19 percent as commercial beekeepers. Thirty-four percent of respondents lost all their bees.

Small hive beetle adults are only about one-sixth of an inch in length and feed on anything inside a beehive: honey, pollen and wax, as well as honeybee eggs and larvae. As they feed, they tunnel through the hive, damaging or destroying the honeycomb and contaminating the honey. In April 2010, some arrived in Hilo as stowaways on a ship or aircraft.

Rasmussen and her partner persevered, carefully nurturing the surviving four colonies to enhance their natural resistance to the invaders. In effect, they were able to compress the natural selection of the remaining bees within “five or six generations,” she says, to create an improved “survivor stock” of honeybees, which, although not impervious to the deadly pests, can coexist with them and keep their numbers under control.

Solomon Singer’s day job is working with horses on Hawaii Island: hoof care, training and teaching humane training techniques. At the same time, he raises bees and, by 2010, he was up to 10 hives when the small hive beetles arrived. “One of those beetles can smell a beehive 20 miles away,” he exclaims, zooming his hand through the air. The pests combined to kill all 10 of his managed colonies. “They wiped me out,” he says.

As purveyor of a prize-winning brand, Bee Mo Bettah Honey, Ron Hanson is one of the established commercial beekeepers on the east side of Hawaii Island. In 2010, he managed 150 hives, some placed along the coast north of Hilo and the rest south, in the Puna district.

The mites and beetles attacked swiftly, leaving him with only 35 surviving colonies. Determined to recover his livelihood, he began researching how mainland beekeepers were combatting the deadly pests.

The beetles are native to tropical Africa and were first detected on the U.S. mainland in South Carolina in 1996, and in Florida in 1998. They spread to many southern and central states and to California. Given their nasty history, techniques have been developed to control them, with and without the use of pesticides.

This knowledge was urgently needed in Hawaii and the Big Island Beekeepers Association swung into action. Led by then-president Cary Dizon, the association petitioned the Hawaii Department of Agriculture and the state Legislature with an 11-point crisis-management plan. Recognizing the serious threat to one of the state’s important cottage industries, elected officials at the Capitol, together with both the state and federal agriculture departments, responded rapidly.

State funding established a new apiary program under the Department of Agriculture, overseen by a state apiary specialist. That specialist, Danielle Downey, arrived in November 2010, and now heads an office with a staff of three based in Hilo near the UH campus. Downey brings 20 years of academic, corporate and governmental apiculture experience to the job.

“Beekeepers have had to manage these issues on the mainland for decades,” Downey says, “but in Hawaii it has been a perfect storm to go from very little management, ‘bee-having,’ to facing two problems that will wipe you out quickly. The challenge has been for beekeepers to adapt and learn what to look for, make some choices about pest control, and invest more time and resources into their bee health. It has been costly and difficult for them, but we are seeing much success.”

As Downey, the beekeepers association and all involved in Hawaii beekeeping immediately recognized, the main answer to the crisis was rapid and thorough education. Apiary experts were brought in, classes and demonstrations hosted, and information shared collegially. Downey has an annual class at UH-Hilo and estimates that she has conducted more than 50 public presentations. This urgent networking continues statewide today, as the beetles managed to migrate to the other islands.

Oahu has only about 5 percent of the managed bee colonies in the state and a quarter of those belong to Michael Kliks, past president of the Hawaii Beekeepers Association and owner of The Manoa Honey Co. and Island Pollination Services. He manages from 150 to 180 hives, depending on the time of the year, which is a full-time job, “seven days a week, 365 days per year.” Kliks reacted quickly to the pest invasion in 2010 and reports losing only five to 10 hives a year. “But now I work three times as hard for less profit,” he says. “My pollination service is actually more important than the honey production, but, if we keep building on agricultural land, if food production goes to zero here, we won’t need any bees.”

Solomon Singer, after training with Ron Hanson, captured a wild swarm on Hawaii Island, domesticated it and has now built back up to his original 10 hives. “That’s all I can handle by myself,” he says with a smile. He can be found every Saturday morning at the Space Market in Kalapana Seaview behind his golden array of honey jars.

Hansen also recovered his enterprise, and now reports more than 100 hives in inventory. One of his goals is to maintain the reputation of the eastern side of Hawaii Island as a source of pure, natural honey. He controls mites using only “organically approved treatments.” Downey credits him with sharing his newfound knowledge with younger beekeepers and those discouraged by the pest attacks.

Jen Rasmussen not only restored her original apiary of 40 hives, she now has 85 managed colonies. She is an evangelist for natural honey, eschewing pesticides. “I knew that the chemicals would end up in the honey and the wax so I determined not to use them. I’ve been able to keep it all organic.” As for the mites and beetles, “My strategy changed,” she says, “from battling the pests to empowering the bees.”

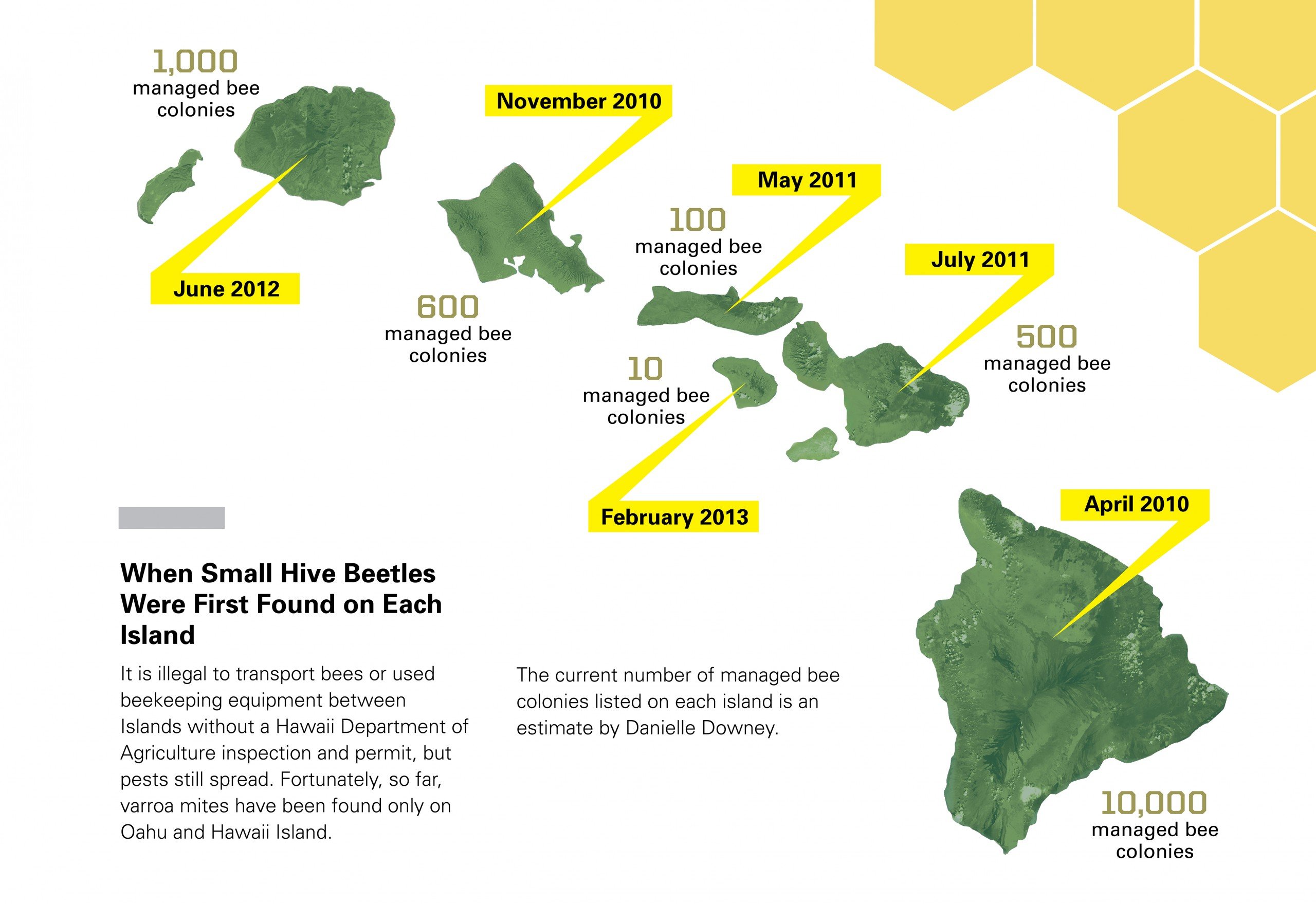

When Small Hive Beetles Were First Found on Each Island

It is illegal to transport bees or used beekeeping equipment between Islands without a Hawaii Department of Agriculture inspection and permit, but pests still spread. Fortunately, so far, varroa mites have been found only on Oahu and Hawaii Island.

The current number of managed bee colonies listed on each island is an estimate by Danielle Downey.

Learn More

State apiary program: www.hawaiibee.com

Big Island Beekeepers Association: www.bigislandbeekeepers.com

Jen Rasmussen’s website: www.paradisenectar.com

Michael Kliks’ website: www.hawaiibeekeepers.org/products-manoahoney.php