The Science of Success – The Success of Science

On nights with a full moon, scientists and engineers from Oceanit gather at Duke’s statue on Kalakaua Avenue in Waikiki, colorful glow sticks fastened around their necks. Toting surfboards, they head for the water’s edge and plunge into the silvery shore break.

“With a full moon, it’s magical,” says Patrick Sullivan, founder and CEO of Oceanit, who often joins the crowd. “Everyone wears a glow stick necklace so we don’t ‘drop in’ on anyone. Three-quarters of the company surfs. It’s hard to find a golfer.”

Those informal moonlit surf jaunts are a testament to the camaraderie at Oceanit, but also to the mindset of the man who leads the pioneering Hawaii high-tech company that, in three decades, has created more than 300 products that are helping shape the future.

Part of the Oceanit leadership team: from left, Chris Sullivan, strategic director, science and technology; CEO Patrick K. Sullivan; COO Jan Naoe Sullivan; mechanical engineer Bobby Izuta; and director Glen T. Nakafuji. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino

Those nights also speak directly to Sullivan’s management philosophy: Find good people, and support them in an atmosphere of trust. No one calls him boss. He’s Patrick. Even his appointment secretary, an Englishwoman with a formidable phone voice, quickly calls you “babe,” and says she’ll “park you” until Patrick comes on the line – which he does almost immediately. That’s despite a schedule that generally has him traveling weekly, including dropping in on the half-dozen Oceanit one- and two-person Mainland offices that help deploy the company further afield.

“When you have highly educated, highly intelligent people and you want them to perform amazing things,” says Sullivan, “you can’t operate with the command-and-control military pattern. You need a more horizontal approach. We want everyone to be a superstar and we try and create an environment where they can be a superstar. You get great ideas by supporting an environment where you have diverse people and diverse thinking.

“We’ve discovered that ideas come from differences, not sameness. When you have different kinds of people from different perspectives and different backgrounds, they develop really good ideas. That’s one of the big strengths of Hawaii.”

Sullivan likes to call the work performed by Oceanit’s 160 employees “the impossible.” That nails it. Imagine the Blast Ninja nozzle that reduces noise exposure at the source; or the Nickel SOAP that plates metal; or the ePop decentralized communication infrastructure; or MAMBA, the all-sky infrared camera for astronomy; or the FLASH system that, in a split second, detects and tracks hostile fire. Unconventional products, yes, but all part of a body of work unprecedented for someone heading a small company based on Pacific islands 2,500 miles from anywhere.

“WORLD-CLASS TALENT”

Oceanit’s CEO has thrived on the unconventional from his “small kid days” in California and Colorado, when the Sullivan brood built their own fantastic creations by scavenging for wires and discarded electronics.

“My brothers and I used to make stuff out of junk parts,” he says. “What otherwise might look like junk, you could build into something. I always found it fascinating to see how things work.”

Out of the need to see how things work – and to do the impossible – has come this thriving company that has helped chart the course for high-technology and innovation in Hawaii. Because of that on-going leadership – and the products Oceanit has produced – Patrick Sullivan was chosen as Hawaii Business magazine’s 2016 CEO of the Year. Not bad for someone who says he wasn’t good at many things in school, though he found math to be “a lot of fun.”

Michele Schimpp, deputy associate administrator of the Small Business Administration’s Office of Investment and Innovation in Washington, D.C., says a company like Oceanit is central to the growth and support of high-tech in a state. Not only does it help build a creative workforce, it inspires young people, pumps money into the economy and offers the core of an alternative industry for the future.

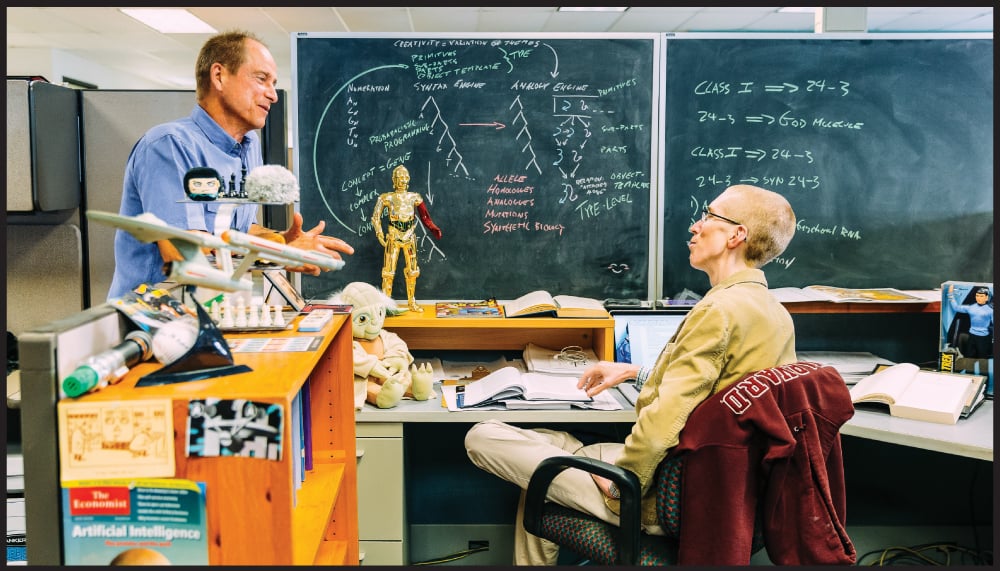

Patrick Sullivan talks with senior scientist Jeffrey Watumull. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino

“Scientific rock stars who work for successful companies become role models for the next generation,” says Schimpp, who gave a keynote address at a recent Hawaii conference exploring Hawaii’s cyber security and innovation future.

“Having that success story is an important foundation. You can look at how brand-names draw world-class talent.

They also generate that stream of talented workers who sometimes venture off and start their own spinoffs.”

Just as the choice of Henk Rogers as 2015 CEO of the Year embraced the importance of entrepreneurial CEOs whose ideas move the community forward, the choice of Sullivan this year recognizes the critical importance of leadership in building new, sustainable, clean industries for the state.

“Patrick is a visionary and Oceanit’s path is the implementation of that vision,” says Ian Kitajima, who has worked with Sullivan for 15 years and is corporate development director for the company. “He’s always looking toward the horizon. Over the last 15 years you’re talking hundreds of millions in research funding. We have spun off three venture-funded companies and they alone have raised over $50 million total. I don’t know how many jobs they’ve created and how many lives they’ve saved, too.”

The accomplishments of Oceanit and Sullivan go hand-in-hand, beginning in 1985 when Sullivan took an unusual step: he opened his own high-technology company in an office on Fort Street Mall. “At that time, the idea of doing tech was not well understood, especially in Hawaii,” Sullivan remembers. “The university had talked about an incubator, but they weren’t ready, so I ended up getting a place downtown. The idea was around research and development, but I had to get pragmatic really fast because anything around research takes a lot of work to set up and get going.

“What I discovered was a need in the market to deal with really weird and hard problems that most engineering firms weren’t comfortable with,” says Sullivan. “They were doing the normal, practical things, and I started doing the weird, impractical things. That created the opportunity to do more research, and from the research came the opportunity to build technology and products. The foundation of that goes back to the fundamental concept of solving problems.”

With the constant difficulty of finding venture capital in Hawaii, it’s remarkable Oceanit has thrived. While anonymous online reviews by former employees regularly point to the company’s dependency on grant funding, with its own built-in unreliability, the fact that 31 years after Patrick Sullivan earned a Ph.D. in electrical engineering at UH, the company he founded is a cornerstone of Hawaii’s small but vital high-tech industry.

To Jennifer Sabas, a key aide to the late Sen. Daniel K. Inouye, and now part of UH’s innovation team, Sullivan’s impact has been profound. “He was a risk-taker,” says Sabas. “He set the path for other companies and innovators to follow, and continues to do that.

“He was one of the original innovators at a time when this sector in Hawaii was nonexistent. In those early days, there were not many companies willing to take the risk and be bold.”

Sabas says she, Inouye and Sullivan worked together “to figure out how to get our companies competitive in the technology sector.” In those days, she says, earmarking federal funds was a typical way to support local companies and the economy.

“Oceanit and Navatek. They were the pioneers. It was their willingness to be risk-takers and grow a sector which is what was important.”

And they did it in Hawaii, Sabas adds. “To make the decision that they were not leaving was a commitment they made to Hawaii that was very important.”

Jay Fidell, technology advocate and founder of the online media organization ThinkTech Hawaii, lauds Sullivan as a foundational force who launched a new industry by leveraging government research funding with Inouye’s assistance.

“They were a local company and they found the magic key for getting money for research,” says Fidell. “A local company doing research – that really was something.”

Oceanit lures brilliant people to Hawaii, and supports brilliant locally educated people, says Fidell. “One of the remarkable things he’s done is to hire these Ph.D.s and tell them, ‘Think of something’ and then, when they did, he’d say, ‘OK, run with it; tell me what you want to develop and I’ll get the funding.’ ”

A challenge has always been getting grants, keeping them and getting new ones, says Fidell. “Patrick is very good at getting grants. But that sometimes works on a ‘fits and starts’ basis, and if you can’t fund a project, you may lose the researcher.”

Working with Inouye when federal earmarks were common, Sullivan built a powerful relationship with military leaders in Hawaii and, eventually, the Department of Defense in D.C.

“Oceanit is a great example of showing other companies how to take advantage of federal programs to move the needle to technology and innovation through small-business programs,” says the SBA’s Schimpp. “The SBA directs about $2.5 billion each year in funding from 11 federal agencies through the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and the Small Business Technology Transfer (SBTT) programs. And, for 22 years, Hawaii appears to have been offering matching funds through the state.

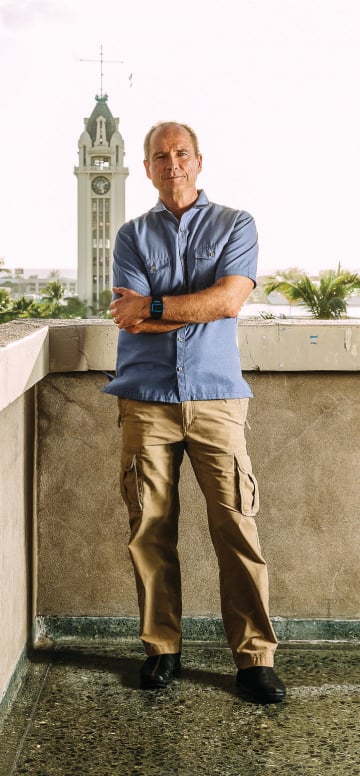

Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino

“Companies like Oceanit are models, demonstrating one can thrive in Honolulu either by attracting government resources or getting third-party investments. It shows they can build a sales base out of Honolulu and that Hawaii is a natural.”

From 2008 to 2015, Hawaii companies received $155.1 million in SBIR grants, according to SBA data. Oceanit itself got $23.7 million in grants through the SBA.

Schimpp says the federal agencies most active in making awards in Hawaii are the departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services, and the Navy and Air Force.

Working with the military has its challenges, Sullivan learned early on.

“You have to develop a credible relationship,” he notes. “It’s hard. In general, DOD looks for help with research in the Beltway between Maryland and Virginia. It requires showing up and talking to people and dealing with people who could be difficult. Persistence is important, and thick skin.” And you have to be good at dealing with rejection, he says. Out of 10 proposals, maybe one will win. “You have to be willing to lose nine.”

But Sullivan had an edge: Pacific Command is located on Oahu, so Oceanit’s engineers can hear firsthand from “warfighters” about issues and problems in the field, and what products could help. “We find it more effective to listen to the folks at the tip of the spear,” says Sullivan, “and then go back and talk to the people responsible for delivering the capabilities to the warfighters. The advantage of the Pacific Command being here gives you a better understanding of what the challenges are.”

DOD is the perfect partner for Oceanit’s innovative approach because it accepts risk in the development of new products.

“The U.S. military has a long history of experimentation,” says Sullivan. “The Department of Defense is an amazing organization and probably one of the biggest investors in the world in high-risk technology. When we think of an idea with a lot of risk, very few will invest in driving that risk down, and DOD is one of them. They invest in early ideas and research that might be too risky for other organizations.

CLICK HERE to check out a few of Oceanit’s inventions

“People talk a lot about venture capital, but they won’t take this kind of risk. They’ll take a business risk, but rarely a technology risk. Venture investing is all about return, and investors don’t like risk, despite the fact they talk about it.”

While the military supports research, he says, it’s slower to acquire the new products it helped bring to life. But it means the products are viable for civilian use, which is much of what Sullivan does with the company now – turning dual-use technology into civilian products.

Take Middle Street. Somewhere along that corridor of ruts and straightaways is an experiment Oceanit has been conducting for a year and a half. Embedded Oceanit nanotechnology has turned the concrete surface into super-hard nanite that also measures the impact as heavy trucks rumble over it.

“A lot of potholes come from heavy trucks,” Sullivan explains, and the “weigh-in-motion” ability of Oceanit’s concrete will detect their impact.

He says it will enable Department of Transportation officials to better understand where and why potholes are made, and how better to fix them.

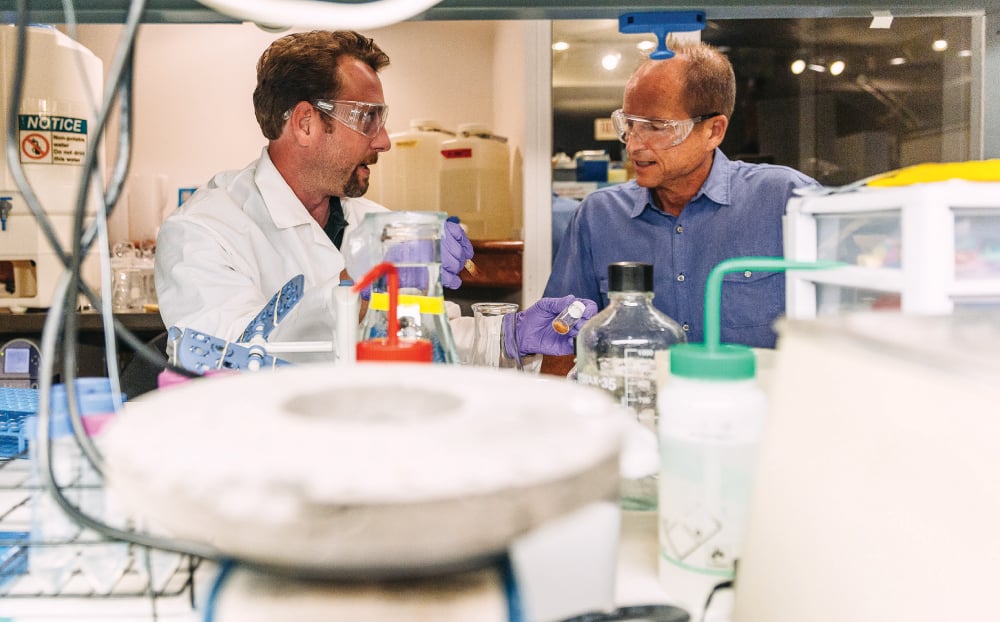

Senior scientist Jacob Pollock talks to Patrick Sullivan in the Nano-Bio Lab at Oceanit’s headquarters on Fort Street Mall in downtown Honolulu. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino

Co-workers admit there’s something both indefinable yet predictable about Sullivan. Indefinable, because it’s impossible to fathom what his engineer’s mind will envision next. And predictable because there absolutely WILL be something he’ll envision next.

That propensity began early for Sullivan. In a family with little money, he applied the innovative entrepreneurial techniques he’d mastered in childhood to pay for his undergraduate degree in engineering from the University of Colorado, Boulder. Tuition came from the landscaping company he founded that was doing projects in three states by the time he graduated. His siblings were equally inspired. His sister is an architect and each of his three brothers is an engineer; the youngest, with a Ph.D. in aerospace, now works for Oceanit.

His own children, a son and daughter, are following in the family footsteps, though Sullivan says he didn’t want to influence them.

“I tried not to tell them what to do,” he reflects. It didn’t work. “My daughter complained sometimes that ‘You have so much fun with what you do, I feel like I should be doing it too!’ ”

She is. She’s working on her Ph.D. in aerospace materials at the University of California, San Diego, studying ‘bio-mimicry,’ and creating new classes of materials, says Sullivan.

His son is equally involved. “He went to Middlebury College to do physics and economics and went to Stanford in engineering,” says Sullivan. “He did a startup in California and is in the process of selling it now – Simple Prints. You take pictures with your phone, and you can click, and a photo-book comes in the mail. Automatically. He developed it as a project at Stanford and it became a business. He did a presentation for his master’s program and people in the audience thought it was pretty cool, and he ended up getting funded.”

The Sullivans raised their children with family surf nights each Monday. He and his wife, attorney Jan Sullivan, who is Oceanit’s executive VP and COO, and current chair of the UH Board of Regents, would pick up their son and daughter at Iolani School, collect their boards from grandma’s house, and head to Diamond Head to surf before dinner. Then it was back to grandma’s, where dinner was waiting.

Sullivan has always known that if he doesn’t build balance into his life, he’ll work nonstop. It’s been that way from the day he started as an entrepreneur after completing his Ph.D. in engineering at UH-Manoa. So, at the end of each week, he evaluates how he’s doing – especially in his personal relationships.

“I sort of made a deliberate attempt on a weekly basis, to be mindful of each person, and to spend time thinking about how am I doing as a husband and a father. It’s important to spend time together, important to make time to do things. You can lose sight of the fact of what’s really important.

“When you work like this, you work a lot,” he continues, “and work can be a lot of fun, but trying to balance that is really important. Trying to always be aware of the balance of family and work is critical.”

He does the same thing at Oceanit. At the end of each year, all projects are evaluated and those that have become nonviable are dumped.

“We do that every year like clockwork. We review what we should be doing; what’s really important; how the world has changed. The concept is very simple – the Darwinian evolution of business. The environment will always be changing and we solve problems, so how do we match them up?

“Every year we have to ask that question: How are we going to make a difference to the world?”

It includes everything from getting rid of paper receipts to ‘What are the big ideas we should be thinking about?’ And that’s part of the discipline of how we operate.”

5 GREAT OCEANIT INVENTIONS

We asked Ian Kitajima, Oceanit’s corporate development director, for his favorite Oceanit inventions.

1/ HONUA: A SPECIAL TEDDY AND THE SICKBAY BED FROM STAR TREK

Hoana technology comes in different forms: The original bed lets caregivers monitor patients whether they are 10 feet or 1,000 miles away. The technology is like the Star Trek sickbay bed: Simply lie on it, and it will pick up your heart rate and respiration. Approved by the FDA for hospitals, Oceanit thinks the bigger market is in elderly and disabled home care, and in a creative car-seat application.

Hoana technology comes in different forms: The original bed lets caregivers monitor patients whether they are 10 feet or 1,000 miles away. The technology is like the Star Trek sickbay bed: Simply lie on it, and it will pick up your heart rate and respiration. Approved by the FDA for hospitals, Oceanit thinks the bigger market is in elderly and disabled home care, and in a creative car-seat application.

The car-seat version includes Honua technology in a wireless, battery-powered teddy bear that transmits vital signs when a child hugs it. Hoana Medical, an Oceanit spinoff, recently licensed its technology to Faurecia, a multinational automotive company. Hoana Medical, Eddie Chen, president, echen@hoana.com, www.hoana.com

2/ INTELISOCKETS: PLUG IN AND TAKE CONTROL

Ibis Networks is an Oceanit venture spinoff that allows large organizations and campuses to measure and manage energy use. Developed with funding from Oceanit, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Office of Naval Research, InteliSockets plug into existing outlets and instantly create an encrypted secure wireless network. Plug in anything – an old refrigerator, window air conditioner or computer system – and the InteliSockets will report real-time energy use. When you know how much and when energy is being used, you can conduct “what if” scenarios to turn on and off electrical devices automatically. The system can be integrated with existing building management systems that are BACnet compatible.

Ibis Networks is an Oceanit venture spinoff that allows large organizations and campuses to measure and manage energy use. Developed with funding from Oceanit, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Office of Naval Research, InteliSockets plug into existing outlets and instantly create an encrypted secure wireless network. Plug in anything – an old refrigerator, window air conditioner or computer system – and the InteliSockets will report real-time energy use. When you know how much and when energy is being used, you can conduct “what if” scenarios to turn on and off electrical devices automatically. The system can be integrated with existing building management systems that are BACnet compatible.

Ibis Networks, Michael Pfeffer, CEO, michael@ibisnetworks.com, www.ibisnetworks.com

3/ VIPA: VERSATILE INFORMATION PROCESSING ARCHITECTURE

VIPA systems ingest, process, fuse and display video and other forms of streaming data (like video from traffic cameras). Kitajima says VIPA goes beyond current programming paradigms that concentrate on individual actions and pieces of data to consider a whole data stream. This high-level view along with a graphical development environment allows users to quickly develop sophisticated applications that might otherwise take weeks to code. VIPA contains a rich set of processing modules that users link to form processing chains. These modules can contain custom-code or call-external libraries. This lets VIPA act as a universal application programming interface that allows the world’s software to work together. Kitajima says you can now apply the best algorithms in a single framework to quickly solve your toughest image-processing problems.

VIPA systems ingest, process, fuse and display video and other forms of streaming data (like video from traffic cameras). Kitajima says VIPA goes beyond current programming paradigms that concentrate on individual actions and pieces of data to consider a whole data stream. This high-level view along with a graphical development environment allows users to quickly develop sophisticated applications that might otherwise take weeks to code. VIPA contains a rich set of processing modules that users link to form processing chains. These modules can contain custom-code or call-external libraries. This lets VIPA act as a universal application programming interface that allows the world’s software to work together. Kitajima says you can now apply the best algorithms in a single framework to quickly solve your toughest image-processing problems.

Technical Lead: Ed Pier, Ph.D.

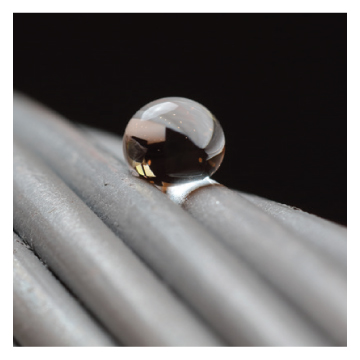

4/ ANTICE: LOW ICE ADHESION ICEPHOBIC COATING TECHNOLOGY

Antice is a nano-engineered coating designed to minimize or eliminate ice adhesion on metallic components. Sponsored by the Air Force Research Lab, Kitajima says, Antice repels extreme water and ice, offers superior corrosion protection and is highly scalable on metallic objects of any shape and size. He says it creates 50 times lower ice adhesion strength than the most commonly used ice repellent and super hydrophobic coatings, according to independent research by the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab.

Antice is a nano-engineered coating designed to minimize or eliminate ice adhesion on metallic components. Sponsored by the Air Force Research Lab, Kitajima says, Antice repels extreme water and ice, offers superior corrosion protection and is highly scalable on metallic objects of any shape and size. He says it creates 50 times lower ice adhesion strength than the most commonly used ice repellent and super hydrophobic coatings, according to independent research by the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab.

Technical Lead: Ganesh Arumugam, Ph.D.

5/ NANITE: SMART SENSING CEMENT AND CONCRETE

Nanite is Oceanit’s smart sensing cement developed for infrastructure, weigh-in-motion, and oil and gas applications. A mix of nano-materials transforms traditional cement into a sensor capable of detecting curing, mechanical load and integrity. Kitajima says Nanite can be used in oil-well and gas-well cementing to ensure long-term wellbore integrity and zonal isolation, improving the economics of drilling and resolving environmental concerns.

Nanite is Oceanit’s smart sensing cement developed for infrastructure, weigh-in-motion, and oil and gas applications. A mix of nano-materials transforms traditional cement into a sensor capable of detecting curing, mechanical load and integrity. Kitajima says Nanite can be used in oil-well and gas-well cementing to ensure long-term wellbore integrity and zonal isolation, improving the economics of drilling and resolving environmental concerns.

Technical Lead: Michael Hadmack, Ph.D.

IF THEY CAN THINK IT, THEY CAN BUILD IT

Patrick Sullivan with Oceanit scientists and engineers. from left, Chris Sullivan, Bobby Izuta and Sedef Maloy in Oceanit’s Product Realization Space. That’s where different teams working on a project can meet to collaborate. The goal is to fast-track products for commercialization; the space is saturated with product information for quick reference. Photo by Aaron K. Yoshino

Ideas at Oceanit come from a specific way of thinking, but must also have a purpose, explains Patrick Sullivan, the company’s chief visionary.

“Everything we do has to find a way to impact humans or society. We usually start with ideas that we think are important,” he says, and then apply a process around “how to think.” He gives an example: the brain.

“We look at what’s going on around the world in a lot of research and then we break it into programs. For instance, we’ll start with the prosthetic brain: How do you help someone with brain damage restore some kind of functionality? Then we start thinking something very risky. One is a brain/computer interface. Another is artificial intelligence, so sensors reading your brain are helping you make good choices. So the idea started with the brain, but this particular program becomes one element in trying to understand the brain, and to do that we find programs where there’s funding that will help us address some of the risk.”

During its three decades in existence, Sullivan says, Oceanit has created 300 or more unexpected products to solve problems and each becomes an exciting project of its own. Like the treatment the company created to reduce ice buildup on wings and other exterior aircraft parts.

“There’s no ice (build-up) in Hawaii,” Sullivan chuckles, “but it’s a huge issue. And the results we’ve gotten from all the testing are off the charts.”

Then there’s a new product being used by oil companies on rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, which might have prevented the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Sullivan says it’s “a nanotechnology treatment for steel casing that we’re working on with Shell and other oil companies. They’ve been deploying pipe treated with this nano material in the Gulf and the results are outstanding. A company like Shell is looking at reducing its costs by using technology, and we developed it here, although originally we developed it for the Navy.”

The new material binds steel and cement better than techniques available now, he says, and means “these things are less likely to pop out of the ground. They’re safer rigs underwater, safer installations underwater.

“When you have nano particles,” Sullivan continues, “the behavior and physics are different because of the scale. When you are building things from a nano scale, you can modify performance in all kinds of ways to make a material do something you never thought it could do.”

Consider the experimental surfboard stationed at the entrance to Oceanit’s headquarters, suite 600 at 828 Fort Street Mall. To test nano technology early, in an actual product, the company built this surfboard with embedded nano titanium particles.

“It wasn’t so much about making surfboards, but more of an experiment to break through a mental barrier and show that we COULD make it,” Sullivan says. “To move things forward, you have to make things. And it led to a lot of other projects. Now we’re looking at this technology roadmap because it has resulted in collaborations with companies around the world with different nano material.”

Oceanit also takes its thinking into the community.

“They (Oceanit engineers) are very active in growing the pipeline of talent in the high schools,” says Michele Schimpp, deputy associate administrator of the Small Business Administration’s Office of Investment and Innovation in Washington, D.C. “They did a design thinking boot camp with 100 at-risk youth for the Department of Education last month. And they inspired local youth to go to the World Conservation Congress. They coach students in robotics and other STEM programs. That stuff really matters. This is exactly the kind of community investment that benefits all sides.”

Schimpp says Oceanit makes a difference in Hawaii.

“They create jobs, attract resources from outside the state, contribute to infrastructure, inspire startups, and engage in active corporate responsibility in a variety of arenas. Oceanit is right in there as part of the entrepreneurial eco-system with partners like UH, the HTDC (High Technology Development Corp.), XLR8UH and other local tech companies. These are the core ingredients when you think of a hub, and there’s Oceanit in a central role.”