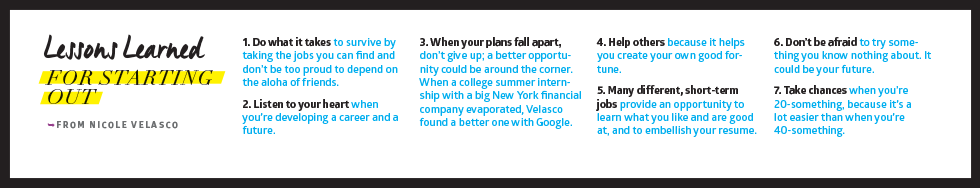

Turning Points

Nicole Velasco: Struggling While Starting Out

Nicole Velasco. Photo: Aaron Yoshino

It was 2008, the depth of the Great Recession, and Nicole Velasco had just graduated from Princeton University. She quickly found that even an Ivy League degree isn’t an automatic ticket to success.

Both her mom and dad had just lost their jobs as Aloha Airlines folded, and both were struggling to retool and survive; it meant no extra money to fly her home.

It was one of life’s defining moments: You either persevere or surrender. “I really wanted to see if I could find a way to make this work,” she remembers, referring to her dream of living and working in New York City. “A lot of it prepared me for what I’m doing today.”

Today, she is the 29-year-old executive director of the Office of Economic Development for the City and County of Honolulu, after working for the state Legislature and the state Auditor, and running for a seat in the state House and losing in a close election.

But, seven years ago, with no job and no place to live, Velasco couch-surfed her way through friends’ apartments in New York and New Jersey for four months after graduation, taking whatever temporary jobs she could find.

“I really loved living (in New York City), but in certain quiet moments, I knew I was not producing anything that gave me joy.”

— Nicole Velasco

She discovered that, when you’re young and relatively unencumbered, it’s OK to laugh at your fear instead of hightailing it out of Dodge. She also learned this was the time to take chances, ask friends for help and explore until you find the job you love.

“I took teeny tiny odd jobs, like selling boutique tonic water in different grocery stores, and event planning for clients I found on Craigslist, and helping a burgeoning PR company get started,” she remembers. “It was stressful, but a good litmus test for the actual job I took, which came out of one of the events I helped plan. It was luau themed, which doesn’t get much easier! At that event, one of the individuals was a VP of an audio post-production company.”

She liked his company and landed a full-time job thanks to her performance at the part-time job.

“We’d clean up and sweeten the sound,” she says, “providing a variety of audio services, having client brainstorming sessions, doing original music. There were some funny occasions, like the time when a client said, ‘I want it to sound like fresh fruit.’ ”

It was great for a while, paid the rent for her own place, and provided free entree to some totally awesome music events, but when it came down to it, says Nicole, it didn’t make her soul sing.

“We find ourselves in situations of need – we need to pay the rent, we need to buy food, we need to survive, and it was a situation of need, which is why I maintained that job,” she says. “But when I really got down to it there was a general slight melancholy I picked up on after about a year and a half. I had a fun life. I was paddling with New York Outrigger. I really loved living there, but in certain quiet moments, I knew I was not producing anything that gave me joy.”

An email from a friend back home in Hawaii about Furlough Fridays changed her direction.

“I had to leave. I knew I needed to help,” she says. “We had put the burden of adults on the backs of children and that was really hard for me, especially since part of my family had been in the DOE and knowing how much my education meant to me. I didn’t know what I was going to do when I came back home, but I had to be part of some positive redirection and I wasn’t going to do that in New York.”

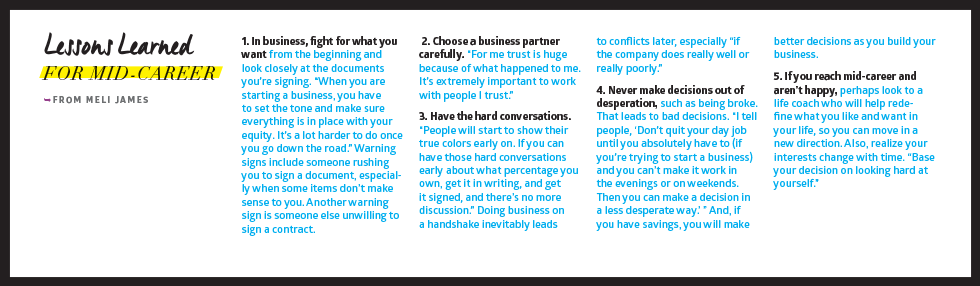

Meli James: Making Mid-Career Choices

Meli James. Photo: Aaron Yoshino

“What’s really interesting about being mid-career,” says entrepreneur and venture capitalist Meli James, “is you have so much to work from. There’s been some success, and a few jobs under your belt. It offers an opportunity to look back and ask, ‘What did you enjoy doing, what did you not, and what were you good at and what were you not?’

“It’s about taking a hard look at that, and then taking a look into the future. Where do you see yourself in 10 years? Do you want to retire at a certain age? What do you want more of in your life? And use those data points to make informed decisions, rather than, ‘Oh, shoot, what’s my next step?’

“As you get a little bit older you get to know what’s important to you. The world is always your oyster, but when you’re younger so many people think, ‘I have to make all the right decisions.’ You look at successful people and you think every move is the right move. That can be overwhelming if you think your next decision is the make it or break it moment.

“But when you look at successful people, many of their decisions may not have been the best, but they learned from them, and that brought them to the point of success. If you do believe that the world is your oyster, whatever decision you make is going to lead to something. You’ll learn from it, and it will put you in place for the next opportunity. Look at the world as an opportunity and an experience to learn and grow. It’s going to be the right thing for you whether it takes one step or three steps.”

“Look at the world as an opportunity and an experience to learn and grow. It’s going to be the right thing for you whether it takes one step or three steps.”

— Meli James

James should know. When she was 27, she went through a “quarter-life crisis.” She wasn’t happy working in research and marketing in the hospitality field, even though she’d trained for it at Cornell University. Turning to a life and career coach for guidance, James realized that working with people, in technology, and with wine, sounded much more appealing and enjoyable. So, she joined with another entrepreneur to start her first company, Nirvino.

“We created the first mobile website for wine,” she says, “and ultimately when the iPhone came into existence we were one of the first wine apps launched, and No. 1 on the iTunes store for three years.”

James owned 20 percent of the company but hadn’t read the fine print of her contract closely enough; she says she ended up with much less than her fair share. It was a difficult learning experience but a mistake she hasn’t repeated. Since then, James has launched three more companies, and now works as head of new ventures for Sultan Ventures in developing other young entrepreneurs and their companies. She’s also president of the Hawaii Venture Capital Association and program director for XLR8UH, an incubator for startups coming out of UH.

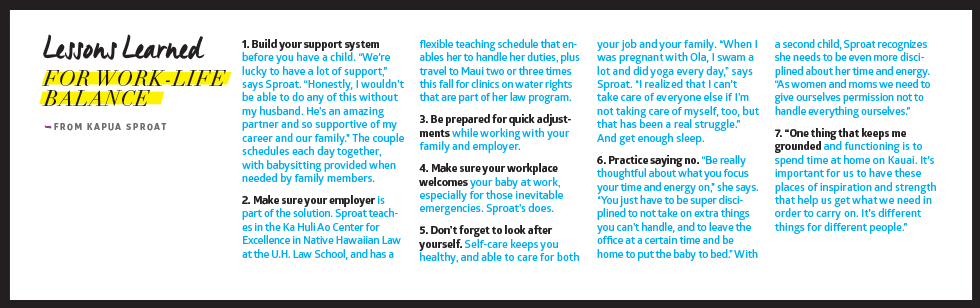

Kapua Sproat: Balancing Family Life and Professional Life

Kapua Sproat. Photo: Aaron Yoshino

As an attorney, law professor and expert on Native Hawaiian water rights, Kapua Sproat works tirelessly. Though she and her husband, Kahikukala Hoe, a teacher and co-founder of the Hakipuu Learning Center public charter school in Kaneohe, always planned to have children, there never seemed to be a right time. They’ve been together 20 years, and married in 2000, but it wasn’t until Sproat was approaching 40 that they planned for a child.

“It was one thing after another,” she says. “It’s like that for a lot of women who are busy and career-oriented. There’s never a perfect time to have a baby.

“After law school, I started at Earthjustice on a one-year contract. I was 23 or 24, and I was in such a rush to get my degree and get out and practice. I want to learn and do as much as I possibly can, so we had to wait a few years.”

When she wasn’t teaching, she was working with community groups that needed legal representation in claims on the use of ancestral streams, particularly for farming.

“We just kept putting it off – after this case, after this trial. There were so many things we were doing,” she says. “But when we had Ola we were so happy. I was 39 when I was pregnant with him, and he was planned, but baby No. 2 was a complete surprise.

“It’s like that for a lot of women who are busy and career-oriented. There’s never a perfect time to have a baby.”

— Kapua Sproat

“He is due in November and we haven’t quite figured out what we’re going to do yet. My husband has three months’ maternity leave but, after that, I don’t know what we’ll do.”

Sproat promised her husband that during her first maternity leave she’d be home all the time, but, when Ola was 6 weeks old, she was drawn into the final settlement of a case she’d been working on for a long time. Gentle, persuasive and compassionate, Sproat’s steady hand and understanding was required. The case was settled, and she finally went back home to baby.

“I had always planned to have more time when I had kids, to spend time with them, and be with them on Kauai (during breaks) and make sure they grew up the way I grew up,” says Sproat. Both she and her husband are working hard to make all of that happen. “My husband and I have made a commitment to go home to Kauai and Kalihiwai at least once a month, a couple of months during the summer and a month during the winter to recharge and rejuvenate.”

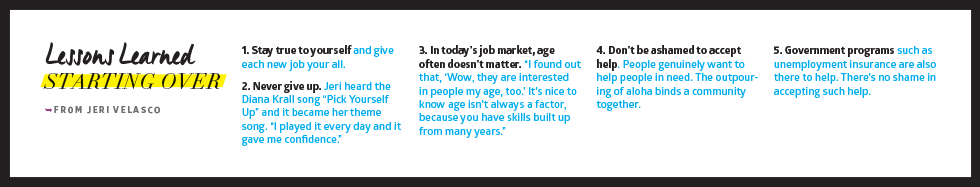

Jeri Velasco: Recovering From a Layoff

Jeri Velasco. Photo: Aaron Yoshino

Right out of high school, Jeri Velasco went to work as a flight attendant for Aloha Airlines. The work was exciting and she loved meeting new people, getting a taste of the world, and caring for the people flying to Hawaii. Thirty-two years zoomed by.

Then, in 2008, her world crashed.

Aloha Airlines closed, leaving 1,900 people – including Velasco and her husband – out of work in the worst part of the national recession.

“I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, what am I going to do? I don’t have a college degree. All I know is Aloha.’ I was very ashamed. I didn’t even want to go out. It was like a death happened and I was grieving.”

Only when her husband, Kevin, insisted she come to a basketball game did she start looking at things differently. At first, she wanted to hide in a back row, but friends and acquaintances rushed up to her with hugs and comforting words. “It was so heartwarming. That support made me feel that what happened to me was OK and people didn’t look down on me. After that I felt alright and decided I needed to snap out of it and start applying.”

Applying for jobs for the first time in three decades was a challenge, but the community opened its arms and hearts to people from Aloha.

“Hawaiian Air just created openings,” she says. Velasco was accepted in the first group of flight attendants, but then had to decline. Her mom was diagnosed with breast cancer and Velasco needed to help her.

“The best thing to take out of a negative job experience is to learn from it.”

— Jeri Velasco

When she was able to take a job, she jumped at the first offer, only to discover after many months that it didn’t feel right.

She tried another, but that also wasn’t a good fit. Discouraged, she had to reconsider her course. “I told myself everything happens for a reason,” she says. “The best thing to take out of a negative job experience is to learn from it.”

At the same time, friends, colleagues and community groups stepped forward with money, gas cards and food cards. TV reporter Tannya Joaquin interviewed the Velascos as part of a news program about the impact of the shutdown on families in which two or more people worked for Aloha Airlines; more money and gift cards poured in.

“It was so humbling and so touching,” she remembers. “I don’t think we could have survived without such generosity.”

Unemployment insurance payments also helped carry the family through until Velasco got a second offer to fly for Hawaiian Airlines and her husband was hired by the Halekulani as a driver and then a greeter, and is now being trained for other departments at the hotel.

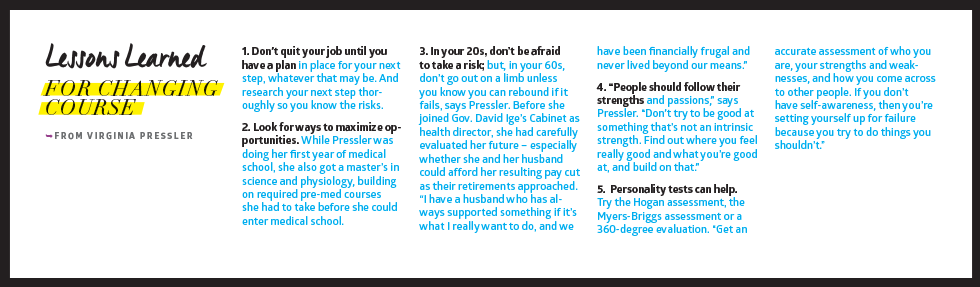

Virginia Pressler: Redefining Yourself Throughout a Career

Virginia Pressler. Photo: Aaron Yoshino

Five years into a solid banking career, Virginia Pressler quit her well-paying job and launched into 12 years of extended schooling in medicine. The first six were unpaid and the last six were only poorly paid, while she did her residency. Though it took years of sacrifice, she says she wouldn’t have traded the decision for anything, as it dedicated her life to a field that gave her great personal meaning.

During those 12 years, Pressler rarely went out, lived on cheese sandwiches she’d eat in the car on her way to work and worked for nominal pay in a research lab. But the lab was also where she first learned surgery, doing operations on live pigs as part of research into the impact of stress on the heart.

“It’s critical that your spouse be part of the conversation, about where you’re going

(in your career).”

— Virginia Pressler

Pressler was 27 when she gave up banking and almost 39 when she completed her surgical residency. Later she specialized in breast cancer surgery, becoming the community’s foremost expert.

Later, she changed direction again, moving into health administration. She has been a VP at Queen’s Health Systems, president and CEO of Queen’s HMSA Premier Plan, a deputy director at the state Health Department, executive VP and chief strategic officer of Hawaii Pacific Health and now director of the state Health Department.

Certain things should be in place when you change careers, she says.

“At that time (when she quit banking to pursue medicine) it was the right thing to do. I was at a stage in my life with no children and a spouse who was working and I could afford to take that risk. But it’s critical that your spouse be part of the conversation, about where you’re going (in your career). My pay during my residency was a minimal stipend that barely covered rent and food.”

Pressler says so much of what you learn during past careers is useful as you move in new directions. For instance, the MBA she obtained before she trained to be a doctor helped when she went into hospital administration.