Working with a Bully

EXECUTIVE COACH KIM PAYTON recalls being asked to help with a case of workplace bullying. Just one problem: Who was bullying whom?

“This guy is a mid-level manager,” Payton says. “He’s new to the organization, so he doesn’t understand a lot of the procedures. He’s a big guy, and when he gets frustrated, he turns bright red, and he starts talking louder. He works with all women, and they were calling him a bully.”

But when Payton took a closer look at the situation, he saw another side. The manager’s subordinates, resistant to his authority and resentful of his domineering style, had been casually ignoring his directions and requests. Each time that happened, his frustration would boil over again.

“It could turn into a game: ‘We don’t need to do what so-and-so says, because he’s a bully,’ ” Payton recalls.

The case illuminates ways in which bullying can be both disruptive to the workplace and challenging to address. Experts say cases of open violence or threats by one employee against another are relatively rare. Far more common are the many smaller, sometimes daily aggressions that might range from a raised voice or cutting remark toward a subordinate, to a passive-aggressive refusal to respond to emails, or a favorite stapler that repeatedly goes missing.

“Use a very soft, quiet voice, and that tends to bring the tensions down.”

— John Knorek, Attorney

In many cases, it all boils down to perception. What’s bullying to one employee may merely be blunt directness to another. Especially in Hawaii, where social norms suggest a softer communication style, simply being less than friendly can sometimes be labeled as bullying by a sensitive employee, experts note.

“It’s a minefield,” says Payton, an organizational psychologist who consults with local businesses.

There’s also “reverse bullying,” where employees undermine managers’ authority by ignoring their requests or showing subtle signs of disrespect, then jump on any expressions of anger or frustration with an accusation of abuse.

“It’s a way to shut the manager down,” Payton says.

Even more complicated cases involve several different layers of bullying at once. Payton determined that’s what was happening with the alleged bully mentioned at the beginning of this article.

Payton ended up working with the manager to help him learn better strategies for dealing with his stress, and worked on changing the way he exhibited his frustration; he wasn’t aware of how his speech and face were affected by his mood. “He needed to be told to watch that stuff,” Payton recalls.

At the same time, a higher-up boss stepped in to increase the manager’s authority within the department and make it clear to subordinates that following the manager’s instructions was mandatory. Those changes addressed the root of the problem, reducing the manager’s underlying source of stress.

“There are some people who are just raging jerks, and they need to be dealt with in an immediate and direct way,” Payton says. “But (many of) these interpersonal issues in the workplace are systems issues.”

Cause for Concern

While bad behavior in the workplace may be timeless, experts agree that the label “bullying” is only recently in the spotlight, and businesses are seeking to address issues of employee hostility more than ever before.

“Ten years ago, we didn’t talk about bullying,” says Anna Elento-Sneed, a Honolulu attorney who represents employers in employment law. She notes that, in a 2007 survey by the Employment Law Alliance, 44 percent of American workers said they had worked for a supervisor or boss they considered abusive, and more than half had experienced or witnessed abusive behavior by a boss.

What’s changed isn’t the behavior, but the standards. A generation ago, “Bosses did what they wanted to do,” says Payton. “You got yelled at, you got screamed at, you got tables pounded on, you got things thrown at you. It’s just the way it was.”

“We have such a relational culture in Hawaii. here, it’s important for people to like you.”

— Kim Payton, Executive Coach

With the passage of workplace safety laws and regulations, employers began to realize they could be held liable for hostile and unsafe work environments. Today, employers are also concerned about the larger effects of a bullying culture on employee productivity, morale and retention.

That can affect the bottom line, notes Gary Farkas, a Honolulu psychologist who works with employers on hiring and management issues, and has advised businesses on workplace violence intervention and prevention.

“You have people who are taking leave; their medical costs may increase because of the impact of the bullying on the person’s health,” he notes. “Productivity declines, people aren’t coming to work or are distracted at work. Their job satisfaction will be reduced, so you might have a good employee who’s leaving rather than staying.”

Payton points out research has found that intimidating employees makes them defensive, engages their fight-or-flight response, and reduces their ability to reason and think clearly. An executive who abuses employees or fosters a bullying culture can cause damage that takes years to undo, he says. “The good people leave, and the people who don’t think they can get a job anywhere else are the only ones who stay,” he says. “It’s like a poison pill.”

“Designed for Control”

What makes bad behavior bullying? “Incivility” might involve garden-variety rudeness or mild hostility, but there’s no clear intent to harm the other person, Farkas says. In contrast, bullying “is deliberate and repeated, designed to control the other person,” he says. “The intent is the difference.”

In some cases, bullies may demonstrate blatant hostility or aggression – repeatedly interrupting other employees in meetings, yelling at or ridiculing them. Bullies may throw their rank around, flaunt their status or be openly condescending toward a subordinate, Elento-Sneed says.

She says many cases of alleged bullying stem from poor management skills. “Sometimes I think they don’t know how to be effective in their communication, so they get louder and bigger to get their point across, and they don’t realize they’re intimidating the person on the other side,” she says.

“The good people leave, and the people who don’t think they can get a job anywhere else are the only ones who stay. It’s like a poison pill.”

— Gary Farkas, Honolulu Psychologist

Payton calls that type the “clueless bullier,” and says the situation often arises when an employee changes roles within the organization. New managers may not immediately understand how their change in status affects their relationships with other people, or that comments that may have been funny or innocuous before will now feel scary or hurtful. “People take very much to heart what the boss says. It’s like you’re walking around with a megaphone suddenly, amplifying everything you say.”

Others may not appreciate the effect their physical characteristics have on others. “Big people don’t understand they’re imposing,” he notes. “If they have a deep voice, that might be scarier.”

Sometimes, people may just not know how to do better. “You’re only as good a manager as the bosses you’ve had, and some people have had lousy bosses,” Payton says. “They’ve assimilated a management style that’s really offensive and intimidating, and they just assume that’s normal. They need someone to come along and say, ‘This is not the normal way to be treating people.’”

Sometimes, people may just not know how to do better. “You’re only as good a manager as the bosses you’ve had, and some people have had lousy bosses,” Payton says. “They’ve assimilated a management style that’s really offensive and intimidating, and they just assume that’s normal. They need someone to come along and say, ‘This is not the normal way to be treating people.’”

But not all cases of alleged bullying involve direct intimidation or abuse. Other bullies “try to obstruct” their target, says Elento-Sneed. “The target calls, and the bully just refuses to pick up the call,” she says. They might develop a habit of strolling into meetings late or ignoring requests. “It occurs so often that it starts to obstruct victims’ ability to do their work.”

The aggressor might damage or disrespect the victim’s tools or workspace. In one case, an employee “absolutely insisted that the bully would take her trash can and pour all the trash on her desk and take away the trash can,” Elento-Sneed recalls. In other cases, the bully might “just stare him down and intimidate him.”

In other cases, “Sometimes, people just think something’s funny, and it’s not,” says John Knorek, an attorney who handles cases of management and employment law. “They’ll go out drinking and make someone drink too much, or they’ll take pictures of someone when they’re drunk and post them on Facebook. That kind of behavior can be bullying, but it’s not for any purpose other than that person thinks it’s funny.”

Hawaii can be a more complicated environment in which to deal with bullying than elsewhere in America, Payton says. Because people tend to be more sensitive to interpersonal conflict, local employees are quicker to label unfriendly or intense behavior as bullying.

“We have such a relational culture in Hawaii,” Payton says. “Mainland culture tends to be more performance based: ‘I don’t care if I like you, just do good work.’ But, here in Hawaii, it’s important for people to like you.”

“What may be mean to one person may be normal to another,” Elento-Sneed agrees.

“Think about what happens if you take a New Yorker – a really loud one – and bring them to Hawaii and make them a supervisor and put them in a group of Asian-Pacific Islanders,” she says. With different communication styles, it may be hard for the New Yorker to get his point across or be understood. “He gets louder and, after a while, is that bullying or harassment, or is it just a different style of communication?”

That ambiguity can contribute to bad behavior going unchecked. Knorek notes that most cases of bullying are brought to management’s attention when one employee makes a complaint. But that doesn’t mean others didn’t experience the abuse.

“At least half the time there’s evidence that the bully was a bully to other people as well, but we all have different tolerance levels,” he says. Some people can roll with the punches, other people get really disturbed by that behavior.”

Ounce of prevention

What to do when there’s a bully in your workplace? From a legal point of view, it’s important to determine whether the hostility is “status based” or “status blind,” says Elento-Sneed. Status-based bullying targets a specific, protected group of people; for example, a boss who picks on women or gay employees. These cases may violate anti-discrimination laws, she says.

Status-blind bullying can be harder to go after legally, but can be just as disruptive in a work environment. “It’s the proverbial equal-opportunity harasser,” she says.

She and other experts agree that one of the most important steps an employer can take is to make sure the business sets policies outlining acceptable standards for behavior and communication in the workplace. For example, a policy might specify that employees should not raise their voices when speaking to each other, Knorek says. Later, if someone yells at a co-worker, HR can show the behavior is a clear violation of workplace conduct policies, and follow up with a reprimand, sanctions or training.

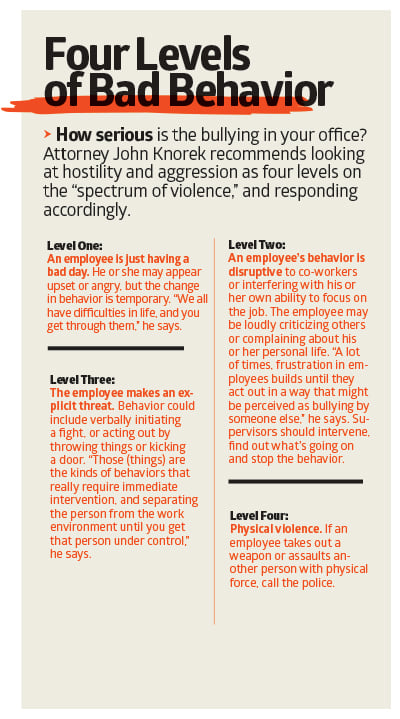

While some behaviors – like explicit threats or the use of physical force – might be unacceptable in any workplace, other guidelines will differ from place to place. “Each company has to decide what that standard is,” Knorek says. “Probably the behavior in a shipyard is going to be different from the behavior in a law firm.”

“Prevention is the key, and prevention is based on having good policies, making employees aware of those policies and following those policies,” Farkas says. Other important steps include making sure employees have a safe way to report misconduct, and making an Employee Assistance Program available as an anonymous way for workers to get help.

Farkas also counsels employers to avoid adding potential bullies to the team by looking for red flags in the hiring process, such as checking for a history of short-term employment, and even noting how the candidate treats the receptionist and other people encountered during the application process.

But if bullying does occur in the workplace, Farkas says, the employer should closely investigate what’s actually happening. Beyond simply determining whether the allegation can be confirmed or dismissed, in some cases, an investigation might tease out a situation of multilayered bullying and reverse bullying, like the one Payton dealt with. Farkas has seen other cases in which the employee making the complaint was impaired or had a mental health condition that made that person paranoid or delusional. In those situations, the correct response might be to help the employee get treatment. “Not all complaints of bullying have a reality base,” he says.

Managers should also receive training in how to respond if hostility escalates to violence or threats of violence, Knorek says. Simple but important steps can include separating the two parties, taking the person out of the immediate work environment to a separate area, sitting down, and keeping a desk or another large object between you and the other person. “Use a very soft, quiet voice, and that tends to bring the tensions down,” says Knorek.

If harassment or aggression becomes a repeated problem, the target of the abuse can seek a temporary restraining order against the bully, he notes. Although Hawaii law currently only allows TROs to be issued to individuals, a bill before the Legislature would offer the same protection to businesses and organizations, he notes.

What should employees do when they find themselves the target of a bully? The first thing is to speak up, says Elento-Sneed. “We teach kids to do this in pre-school: if somebody’s doing something you don’t like, say, ‘I don’t like that,’ so at least they know,” she says. “Nine times out of 10, they’ll stop. But if they keep going, that’s what HR is for.”

Payton says it’s always worthwhile to speak to bullies about their behavior and give them an opportunity to change. Sometimes, the problem might be an executive brought in from the mainland with a poor grasp of Hawaii’s cultural differences and an aggressive agenda of change. In those cases, intervention can improve the atmosphere in the workplace and make the person a better executive for the long term.

“Some of them really get it. Hawaii mellows them out, and they learn a more influential, rather than coercive style of management. Even their families appreciate it,” Payton says. “Or, they don’t get it. They think it’s just BS. And those people need to be removed.”