Hawaii’s Dreamers

Muscular and athletic, Shingai Masiya was certainly college football material. He hoped for that coming out of high school, but the dream died. While he had come into the U.S. legally at age 13 with his family from Zimbabwe, a permanent visa wasn’t processed in time, leaving him today as a Dreamer, a young adult who grew up in America but lacks legal immigrant status.

Without that status, Masiya couldn’t play football anymore, enroll in college or get a Social Security number. He couldn’t legally get a job or a driver’s license. He also couldn’t pay income taxes, or plan for his future or a family.

Dreamer Shingai Masiya. Photo: Sean Marrs

“I had a couple of offers to play football as a student athlete but I couldn’t take advantage of them,” says Masiya, now 30. “Imagine waking up every Saturday morning and watching people doing what you want to do but can’t.”

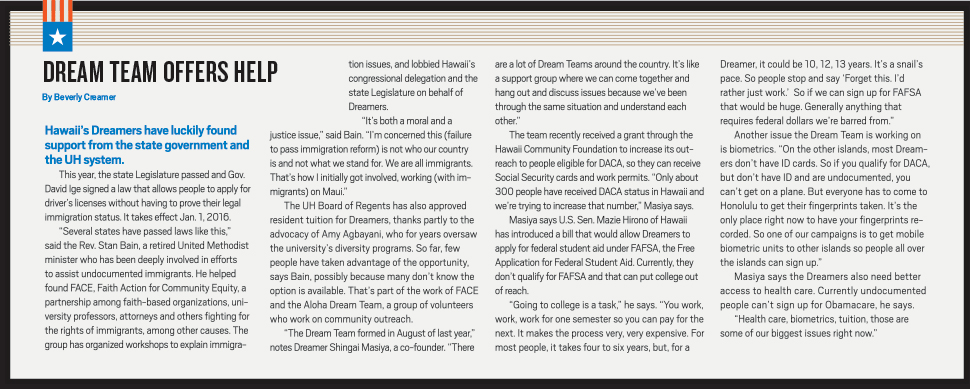

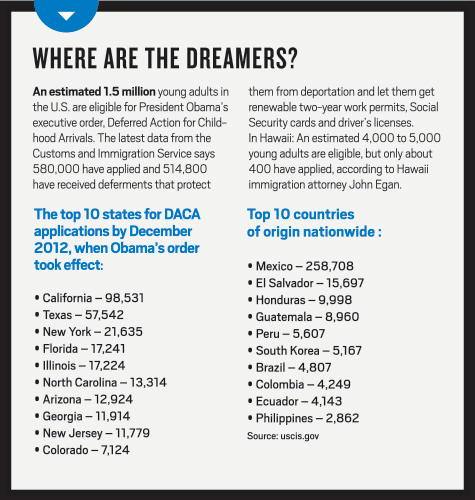

Masiya is one of about 4,000 to 5,000 Dreamers in Hawaii who are trapped in the crossfire of national immigration politics. Part of a lost generation of 1.5 million nationwide, they were brought to the U.S. by their parents as children, attended American schools and now are young adults. In their eyes, they are Americans. If deported, they would return to homelands that would feel alien or they can’t even remember.

Without documentation, they had no legal way to stay in the U.S. permanently until given a reprieve by President Obama’s 2012 executive order called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. DACA lets them get temporary work permits, Social Security cards and driver’s licenses, but offers no path to permanent residency or citizenship.

A new president could rescind that order and, until Congress passes a permanent law on their behalf, Dreamers say they will never feel secure.

“I feel that Congress has held my future hostage for the last decade, and they continue to hold it hostage,” says Gabriela Andrade, 29, who came to the U.S. as a teenager when her family fled violence in Brazil. “I’ve been working house-cleaning, babysitting – under-the-table jobs – but I always had good grades and knew I had a huge potential, but couldn’t live up to it.”

Even for those who qualify for DACA, the risks remain palpable. If a new president rescinds the policy, those who registered under the program fear they could be deported. In fact, Hawaii Dreamers on average have been far more hesitant to make themselves known and sign up for the program than those on the mainland. As welcome as DACA was to many Dreamers, it has many limitations.

“What DACA doesn’t do is help the parents of someone who is a Dreamer and that is very disappointing to a lot of the DACA kids,” says immigration attorney Maile Hirota of Hirota & Associates. “And that’s why some kids have been hesitant to apply because they worry it will expose their parents to immigration authorities, who may try to deport them.”

“The one thing people don’t understand about Dreamers is the depression. It’s a big part of our lives. You can’t feel normal, all because you don’t have a piece of paper.”

— Shingai Masiya,

Dreamer originally from Zimbabwe

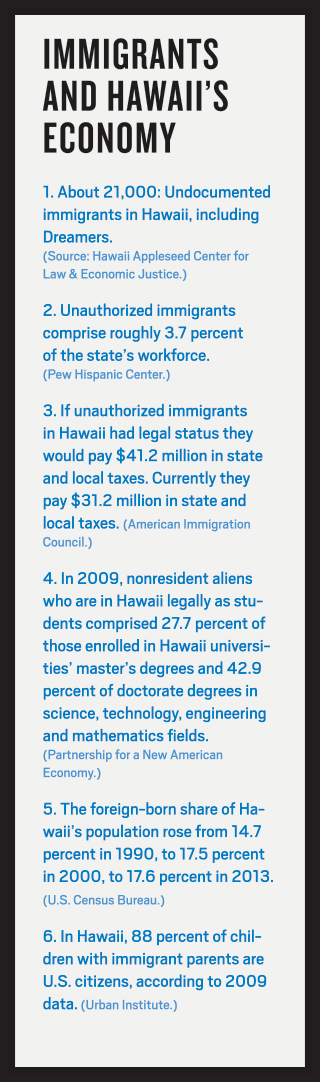

The uncertain future for Dreamers hurts Hawaii and America on many levels, says the American Immigration Council, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization based in Washington, D.C. that is dedicated to educating Americans about immigration. In a May 2015 report, the Council noted the economic strength that immigrants bring to Hawaii. Quoting statistics from the University of Georgia’s Selig Center for Economic Growth, the council said that Latino buying power in Hawaii totaled $3.9 billion in 2014, an increase of 308 percent since 1990.

“If all unauthorized immigrants were removed from Hawaii, the state would lose $2 billion a year in economic activity, $900.3 million in gross state product and approximately 8,460 jobs,” the council reported.

The Rev. Stan Bain, who helped found the interfaith group FACE – Faith Action for Community Equity – says Hawaii should care greatly about these young people.

“They are part of our communities,” says Bain, a retired United Methodist minister and now a social activist on behalf of Hawaii immigrants. “Some have lived here a long time and raised families. Their lives here are important, whether they start businesses or work in other businesses. We did a rough estimate of what the state of Hawaii stands to gain if DACA and the other reforms are allowed to move forward and it’s millions of dollars of additional revenue coming into the state.”

“We’re disabling a whole generation of people,” says immigration attorney John Egan, who was a field officer for the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees before earning his law degree. “What happens when you take a group of people and you prevent their human potential? There’s an opportunity lost to society. But you’re also channeling those people. When they get to the end of their high school years and they hit a dead-end and can’t get jobs or go to school or get scholarships, what happens? Are we encouraging them to go and steal and hang around on street corners and find petty mischief to get into? That’s crazy. You can’t take a group of people and make them an underclass and expect them to be OK.

“By preventing them from getting documents, we’re encouraging them to do things that are not socially useful and that’s just a bad idea,” continues Egan. “We have lost these young people who would be happy to go into the military, get a good education and get a job and help their families get ahead.”

Andrade agrees.

Dreamer Gabriela Andrade. Photo: Sean Marrs

“The system is broken,” she says. “It doesn’t give a lot of people a pathway to come here legally. If I went back to my home country (first), it wouldn’t make any difference. There isn’t a visa that allows me to come to America. A work visa requires you to be extremely skilled, but most of us don’t fall under that category. Student visas are extremely expensive and we can’t afford them, and a lot of us don’t qualify for the family visa as the system is right now.”

Andrade was a teenager when her family fled violence in Brazil almost 15 years ago and came to the U.S. on tourist visas.

“We came to Texas initially, and the idea was to wait out the terrible times our country was going through, maybe one or two years. But when my parents saw they could live in a place that was safe for their children, and they could go to school, they fell in love with the U.S.”

“I feel that Congress has held my future hostage for the last decade, and they continue to hold it hostage.”

— Gabriela Andrade, Whose family fled violence

in Brazil when she was a teenager

The family stayed illegally. Andrade can’t forget the day a phone call came when she was getting ready for school and her family still lived in Texas. “Don’t come to school today,” warned a trusted friend. “They’re starting to do immigration checkpoints on the road.”

Then came a lifeline for her family. A “green-card lottery” begun by Congress in 1995 enabled 50,000 immigrants from countries with low rates of immigration to the U.S. to gain lawful status each year. Gabriela’s older sister was lucky: She was a lottery winner and then she successfully petitioned for their parents to become legal immigrants, too.

“When she petitioned for my parents I was over the age of 18, so I was considered too old,” says Andrade. “I fell through the cracks. So at 18, I was faced with the dilemma of ‘Do I go back to Brazil all by myself or do I stay here?’ I knew I couldn’t go back to that place alone, but there was no way for me to stay legally.”

Federal legislation that would have granted legal status to such children of immigrants was first introduced in 2001, and passed by the Senate but never by the House of Representatives. Obama’s DACA executive order in 2012 – issued over the objections of congressional Republicans – exempted from deportation those who were under the age of 31 by June 15, 2012, had lived in the U.S. continuously since June 15, 2007, and had come into the U.S. as children with their parents but were no longer minors.

The executive order also made them eligible for Social Security cards, driver’s licenses and two-year work permits with the possibility of a second two-year extension.

Masiya becomes emotional when he talks about the day his work permit arrived in the mail. “When I opened it up I saw this little card the size of your driver’s license and I wept. It was like, ‘Wow, I can finally go after my goals and my dreams and I can finally do what I want. The first order of business was heading for the Social Security office. I was there for five minutes and she said, ‘OK, you’ll get your card in two weeks.’ I don’t think she understood the magnitude of that moment for me. She made it seem so simple, yet it was something that had evaded me for years and years.”

Masiya is now a student at Hawaii Pacific University, has worked for Sen. Brian Schatz, and is heavily involved with Hawaii’s Aloha Dream Team to get the word out to other Dreamers about DACA and the possibilities it offers.

“I’ve seen the huge impact it (DACA) has made on these young people who have blossomed and gotten closer to achieving their full potential. They can walk around and, at least for the moment, feel unafraid.”

— Maile Hirota, Immigration attorney

Immigration attorney Hirota remembers the excitement at the annual conference on the mainland of the American Immigration Lawyers Association after Obama announced DACA.

“There were thousands of immigration lawyers at the conference, and there was this great cheer,” says Hirota. “But, after that, we all wondered what would this mean. I remember feeling a little bit nervous. Is it for Homeland Security to build this big database to use against undocumented young people? I had a wary eye, but, in the three years that have passed, I’ve seen the huge impact it has made on these young people who have blossomed and gotten closer to achieving their full potential. They can walk around and, at least for the moment, feel unafraid. And some people have received permission to travel internationally to see family members like grandparents they haven’t seen for years.”

Hirota has also proudly watched Dreamers find their own voice in Hawaii and across the country, to become politically active and lobby on their own behalf. (See accompanying story.)

“I’m really all for it now,” she says of DACA. “It has been a tremendously great thing.”

When the U.S. Senate passed an immigration reform bill, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity and Immigration Modernization Act, hope blossomed again.

“We thought we were so close to finding a solution and having a future,” remembers Andrade. “It would have provided a pathway for citizenship for those already here. Those of us who had DACA would have been able to petition for citizenship. But then (U.S. House Speaker John) Boehner didn’t even bring it to the floor of the House. We’re always getting the rug pulled out from under us.”

In November 2014, Obama issued another executive order to expand DACA. It would have enabled undocumented immigrants who entered the country as children before Jan. 1, 2010, to be exempt from deportation and receive renewable three-year work permits rather than two-year permits. His new order would also have eased rules for the parents of Dreamers. However, that executive order is tied up in court battles and not in effect.

“It’s nice to be able to work, but it’s not a final answer to solving my whole immigration

issue.”

— Mahe Vakauta, a Dreamer who came

to Hawaii from Tonga when he was 5

Immigration attorney Clare Hanusz, of counsel at Damon Key Leong Kupchak Hastert, has been involved in dozens of immigration cases on behalf of young adults. She says DACA was a breakthrough, but hasn’t solved all the issues.

“Those who qualify under DACA have the ability to gain temporary status, basically a reprieve,” she says, “but they’re still very much in limbo. And, for a large number of those children, there’s no immigration remedy for their parents.”

Egan agrees. “On the mainland, 85 percent or more of the undocumented kids are from Latin America. But here our population is very different. We probably have many more Filipinos, Koreans, Chinese and Pacific Islanders, and those communities are different in the way they react to public policy. There’s a much bigger concern about what the effect would be on their families if they revealed their status, as well as the social stigma of being undocumented. The combination of cultural factors, and not really having social services for outreach like the mainland, combine to make it difficult.”

Hanusz says an individual’s status is dependent on his or her status as they entered the U.S. “For instance, people who are coming from the Pacific islands, if they come to Hawaii and overstay, at least they had a lawful entry. But, if you entered illegally – and have been in illegal status for more than a year, and then leave the country – you face a 10-year re-entry bar.”

Even if a person enters legally, overstays for a year and then leaves the country, he or she faces a 10-year re-entry bar, says attorney Egan.

That’s exactly what keeps many undocumented immigrants in the shadows and working for under-the-table wages.

Dreamer Mahe Vakauta. Photo: Sean Marrs

“You can’t plan,” says Masiya. “When a Dreamer tells you, ‘I don’t know’ (about my future,) it’s really I don’t know.”

Masiya says he took a chance on DACA because he could no longer live under the radar, always fearful, always looking over his shoulder.

“I was tired of living the way I was living …. I felt as if I was honestly going to give up on life if I hadn’t taken advantage of the DACA program. If I had lived the last two years without it I don’t think I would have made it.

“Those who qualify under daca have the ability to gain temporary status, basically a reprieve, but they’re still very much in limbo.”

— Clare Hanusz, Immigration attorney

“The one thing people don’t understand about Dreamers is the depression. It’s a big part of our lives.”

Mahe Vakauta, who came to Hawaii from Tonga as a 5-year-old with his parents, also took the chance. Registering for DACA stopped deportation proceedings against him.

“It’s better than it was before,” says the 27-year-old graduate of Campbell High School, class of 2006, who now has two legal part-time jobs: as a transport driver for a car rental company and as a worship leader at a Kailua church. He’s also signing up to go to Leeward Community College and hopes to eventually study for the ministry.

“It’s nice to be able to work, but it’s not a final answer to solving my whole immigration issue,” he says. “It’s still a stepping stone.”

Vakauta also got caught up in his family’s lengthy process of immigration paperwork filings. By the time his parents received legal status, he had aged out, just like Andrade.

“Everyone else (in the family) had gotten married,” he says, “so it was only me left, and I got filed under my parents when I was 18. The process took a long time. We filed paperwork and then we’d get it back and something would be wrong. When we went in for our interview, the person said my parents would get cards first and I would get mine after. They got theirs, but a few months later I got a letter saying I had to go to court for deportation proceedings. I had turned 21.”

Judges have told him to get married, he says, but he refuses that option. “I really don’t want to get married that way, to stay here. That doesn’t seem a good reason to get married. It would just mean I’m trying to get something from that person.”

“When they get to the end of their high school years and they hit a dead-end and can’t get jobs or go to school or get scholarships, what happens? Are we encouraging them to go and steal and hang around on street corners? … That’s crazy.”

— John Egan, Immigration attorney

In any case, marriage to an American isn’t a magic bullet, says attorney Hanusz.

“For the majority of the kids who quality for DACA, most came without any status at all,” she says. “Even if those folks married a U.S. citizen, they have no way of getting lawful status. Say, for example, someone’s parents brought them from Mexico when they were 5 and they crossed illegally over the border and that person lived here 20 or 30 years, did everything right and then married an American, they still could not get status because there was an unlawful entry at first.”

Vanesa Garcia understands the uncertainty of being a Dreamer, but still keeps moving forward. She just finished her first year at Leeward Community College under DACA status and is returning this fall. Garcia came to the U.S. at age 5, fleeing from potential violence directed against her family in Mexico. While she was applying for her first two-year DACA permit, she says, her father was filing for political asylum.

These four Dreamers have a short-term reprieve from deportation, thanks to an executive order from President Obama. But their long-term immigration status is uncertain. From left, Mahe Vakauta, Gabriela Andrade, Vanesa Garcia and Shingai Masiya.. Photo: Sean Marrs

Garcia, a 2014 graduate of Waialua High School, worries that her parents might be deported back to the area in Guadalajara from which they fled. Her youngest sibling is 7 and was born in the U.S.

“When I see pictures of the area around Jalisco in Guadalajara, it’s nothing close to what I think it’s like,” she says. She pauses for a moment. “I just don’t remember it.”

She may have been born in Mexico, she says, but she also feels American. Then she pauses: “I guess I’d say I’m local,” she adds.