KABOOMERS!

“ABOUT $1.1 BILLION A YEAR IS PAID OUT IN PENSION BENEFITS NOW (TO STATE AND COUNTY WORKERS). IN THE NEXT 10 TO 20 YEARS, THAT’S PROJECTED TO GROW TO ABOUT $2 BILLION A YEAR.”

–WESLEY MACHIDA

Director, State Department of Budget and Finance

Baby Boomers have wreaked demographic havoc on both Hawaii and the nation for seven decades, and they’re doing it again – this time bigger and badder than ever.

The oldest members of the Boomer generation – those born from 1946 to 1964 – will celebrate their 70th birthdays next year. The coming years will transform Hawaii economically, socially and physically, and there are far more dark clouds than silver linings ahead. Here are 10 previews of the future that we will all be sharing.

1. COST OF GOVERNMENT IS GOING UP.

No sector of the Hawaii economy is as dominated by seniors as much as the government. There are more than 67,000 state and county employees, nearly half of whom are Boomers and preparing to retire. And it’s going to cost you. Probably no one understands this as well as Wesley Machida, the new director of the state Department of Budget and Finance. He’s also the former administrator of the Hawaii Employee Retirement Service, the pension plan for tens of thousands of state and county employees. He’s seen the future.

There are more than 118,000 ERS members statewide, Machida says. That means either retirees, current state or county workers, or those who have left government but have the necessary years of service to receive a pension when they become age eligible or get back what they put into the system, plus interest. The growing number of eligible members is a debit on our future, a bill the state is legally required to pay. And we’ll be paying for a long time.

Part of the problem – if that’s the right word – is that Hawaii has the greatest lifespan in the country. For example, the average life expectancy for a retired female teacher in Hawaii is 90 years. That means she may collect her pension for 25 years or more. This kind of longevity adds to the cost of government.

“As people live longer,” Machida says, “it exerts more pressure on the budget because there’s a greater need to put in more contributions to help pay for those benefits. Right now, for example, about $1.1 billion a year is paid in pension benefits. In the next 10 to 20 years, that’s projected to grow to about $2 billion a year.”

The current wave of retirements from state government doesn’t just add to our pension obligation, it fundamentally alters the payment equation. “We have 43,000 retiree beneficiaries,” Machida says, “and 67,000 active members. So, it’s getting close to a 1-to-1 ratio of active members to retirees. Whereas, if you look 20 years ago, I think we had about half the number of retirees – about 20,000 – and we had about 60,000 active members. So, it was a 3-to-1 ratio. As the population is aging and more people are retiring, there’s a greater need to fund the system, through investment income and through contributions.”

All of which raises the question: Can the state government sustain even its current level of services, given the demographic trends?

“At some point in time, it may become di‑ cult,” Machida says. “Currently, the retirement system receives close to $700 million a year in contributions from the employers. The other thing is that, on the health benefit side, the EUTF, there’s a pay-as-you-go amount, which is about $400 million a year. Plus, we’re currently pre-funding part of the EUTF (also known as the OPEB or other post-employment benefits). In fiscal year 2019, the cost of that will be another $400 million to $500 million a year, if we pay in full. That means, in fiscal year 2019, about $1 billion a year would need to be contributed by employers, and approved by the Legislature, for just the health benefits alone. The current general fund for all programs statewide is about $6.5 billion. If that remains the same, health benefits alone would represent more than 15 percent of the general fund budget.” Of course, if you add the pension contributions to the equation, these entitlements and contractual obligations account for nearly a quarter of the general fund payouts.

Even strong advocates for the elderly, like Barbara Kim Stanton of AARP Hawaii, acknowledge the financial problem the state faces.

“I think what you’re going to see,” she says, “is that, with the amount of monies that are mandated by law and have to be covered, it will mean much less in discretionary services. As it is now, when you look at the budget pie, you can see there are very little funds for anything else, whether it’s for economic development, higher education – you’re required to pay for primary education – environmental concerns, agriculture. When you’re looking at the needs of the state, you can see that fulfilling our obligations for the EUTF and pensions and, in particular, Medicaid is going to leave little for anything else.” Indeed, Med- Quest, the state administered Medicaid program, cost Hawaii taxpayers over $1 billion in 2014. By 2024, Med-Quest expenditures will account for fully 20 percent of the state’s general fund.

All this amplifies Machida’s concerns about the costs of an aging population. “In the future,” he says, “are all those (state and county) employers going to have the ability to pay what’s required for their employer contributions? Or are there going to be other programs – health programs, social services, education – that are going to have to be reduced in order to make those payments? To me, that’s one of the issues down the road.”

2. SENIORS WILL DEMAND MORE PUBLIC SERVICES.

A great conundrum of an aging population is that, although people are living longer, they don’t necessarily have more money. This raises the prospect of a swelling population of impoverished seniors, especially given the high cost of healthcare for older people. After all, most of a person’s medical expenses typically occur in the last three years of life.

As Wes Machida points out, this scenario will likely overwhelm the finances of even the lucky few who have pensions. “Currently,” he says, “the average pension is about $25,000 a year for a state and county government retiree. When you talk about the impact, the question becomes: Can people survive on that type of pension income living in Hawaii? If not, they would have to rely on other programs.”

That said, the state’s current budget for long-term senior services is embarrassingly small – about $17 million a year for both Kupuna Care and federal Title III programs, according to Terri Byers, the director of the state’s Executive Office on Aging. She notes that this money, a mix of federal and state funds, provides “services to 7,603 older adults; 1,619 adult, informal family caregivers of older adults (age 60+); and 78 grandparents or individuals, age 55 years and older, caring for a related child or children under age 18 or related individuals with a disability up to age 59.”

These are critical services, but it’s useful to keep the state efforts in context: In 2030, when more than 100,000 Hawaii seniors are expected to be living below the federal poverty level, $17 million dollars will buy about $170 worth of services a year for each of them. Clearly, there will not be enough money to go around.

But that won’t stop seniors (and the family members who care for them) from demanding more government services. The costs of aging outstrip the resources of even solidly middle-class families. Because the price of private care is so high, those middle-income seniors will end up competing with poor seniors for the same public services. It won’t be pretty.

“Right now, virtually every program in the state is only for those on Medicaid,” says AARP director Stanton. “We have a program called Kupuna Care, which was established decades ago in recognition of the fact that there were no programs to help middle-income individuals. Kupuna Care provided services if you needed help for what we call ‘activities of daily living,’ or ADLs. These would include things like bathing, help with chores, transportation, dressing. These are all ADLs. If you needed help for at least two of these, then you were eligible for Kupuna Care. But, in 2013, the Legislature opened this program up to Medicaid. When you think that Kupuna Care gets only $9 million a year and Medicaid gets $600 million, you can see why so many seniors want to know how they can divest their assets so they can qualify for Medicaid.”

3. TAX REVENUE WILL DECLINE

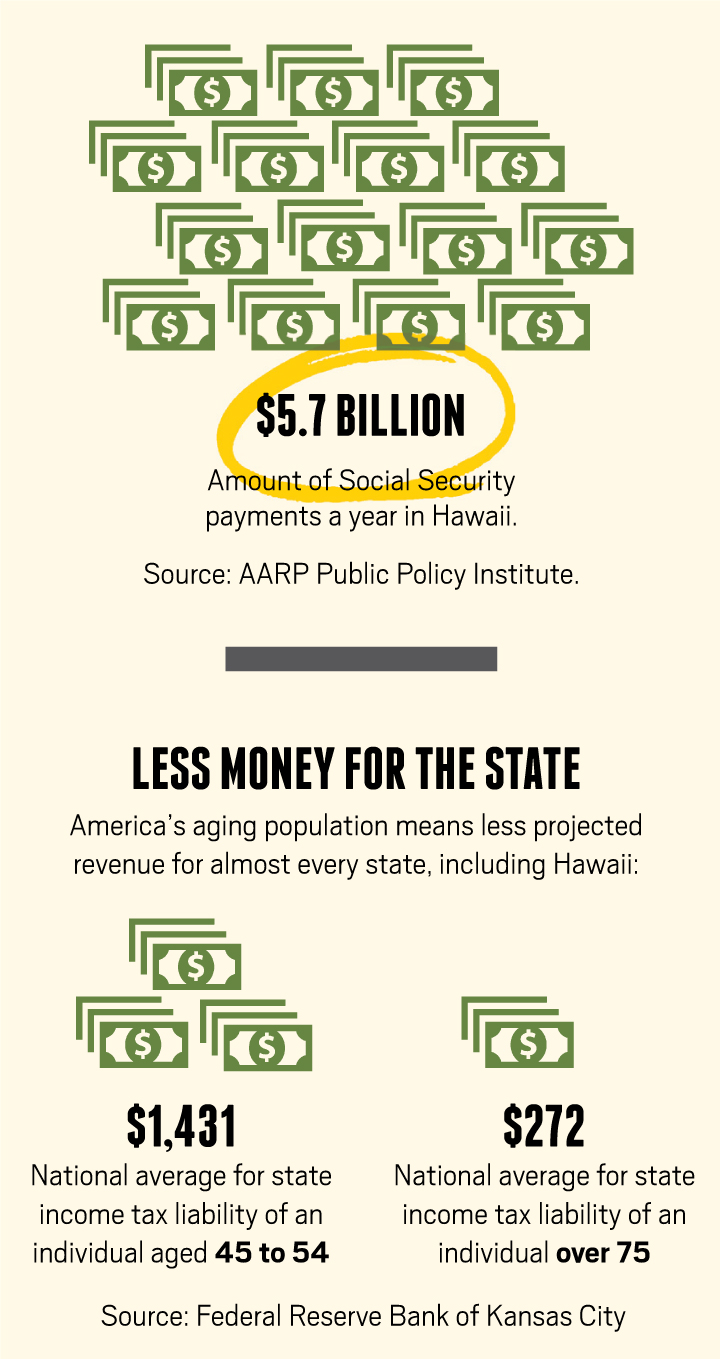

Perversely, even as Hawaii’s aging population drives up both the cost and demand for government services, it will also put a downward pressure on the tax revenue necessary to pay for them. That’s because tax revenues are closely tied to the personal income and spending of taxpayers. Not surprisingly, older retirees generally earn and spend less than they did when they were working.

In a 2012 report for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, economists Alison Felix and Kate Watkins tried to assess the impact of an aging population on state tax revenues. What they found was alarming.

The report points out that, nationwide, the average state income tax liability for individuals plummets from a peak of $1,431 a year for people ages 45 to 54 to $621 a year for those 65 to 74. The annual state income tax liability for people over 75 is only $272. So, by 2030, when the number of seniors in Hawaii approaches 30 percent of the total population, those people will have less than half the tax liability of the cohort behind them. Because of this, the Federal Reserve report projects a decline in Hawaii’s per capita individual income tax revenue of about 12 percent over the next 15 years, slightly more than the 10 percent decline forecast by the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism.

But income tax accounts only for about 27 percent of state revenues. The bulk of our revenue comes from the general excise tax, which most people experience as a sales tax. In one sense, that’s good. Although sales taxes tend to be more regressive than income taxes – they affect poor people more than rich people – they normally provide a broader and stabler tax base than income tax alone. Not in this case, though. As the population ages, Hawaii’s excise tax collections will also likely decline.

In part, that’s because of the decline in income for post-retirement age people. They simply have less money to spend. But the decline in tax revenues is also because of how people’s purchasing patterns change as they age. For example, those over 75 spend an average of 14 percent of their income on healthcare and medication, far more than other age cohorts. Even in Hawaii, which has one of the most aggressive taxation policies in the country (we’re among the few states that apply sales tax to unprepared food, for example), we don’t tax medical care. In other words, not only do seniors spend less, but a higher proportion of what they do spend generates no excise tax for the state. According to the Federal Reserve report, this puts Hawaii at the front of a national trend in which “sales tax collections from the elderly may fall faster than their total spending.” Because of our relatively old population, the report says, Hawaii can look forward to a 3.3 percent decline in per capita taxable spending by 2030.

These kinds of declines in revenue will likely be mirrored at the county level. Although the counties generally rely on property tax rather than excise tax, most of them provide property tax credits to the elderly. So, as the population ages, property taxes will also face downward pressure.

Of course, up to now, we’ve only been talking about per capita tax revenues, which are expected to decline in every state except Idaho. However, the Federal Reserve report notes that, in most states, total tax revenues will continue to rise because of increasing population. Once again, though, Hawaii may be an exception. The state anticipates about a 6 percent increase in total income tax revenues based on a population it forecasts to grow 16.5 percent, largely due to immigration. This growth presumably includes more working-age people. The Census forecast, on the other hand, estimates only 6.6 percent growth in population in Hawaii over the next 15 years. If the Census numbers are more accurate, then we can expect the state’s total tax revenues, not just per capita tax revenues, to decline as our population ages – a grim scenario.

4. MASSIVE TURNOVER IN STATE EMPLOYEES.

Not all problems are financial. One of the biggest issues facing Hawaii is a brain drain of unprecedented proportions. And it’s coming from an unlikely source: state government.

“The Baby Boomers are getting ready to retire,” state budget and finance director Machida reminds us. “There are 67,000-plus people, statewide, working in the government sector – in either the state government or the county governments – and, of those 67,000, at least 15,000 are eligible to retire today.” Roughly half will be eligible to retire within five years. That’s not just a crisis for the pension system; it’s a potential catastrophe for the institutional memory of government agencies, according to Patricia Tomkins, a long-term-care program specialist at the Executive Office on Aging.

“Even in our office,” Tomkins says, “almost 50 percent of us are within five years or less of retirement. So, we’re the ones serving ourselves. And we’re also designing a system that we’re going to have to use.”

That’s not much comfort, though, given the imminent exodus of thousands of government employees.

“What’s the plan?” she says. “There is no plan. That’s the scary part. I belong to HGEA. I used to be on the board of directors. I totally support unionism. But the way we’re set up, unions haven’t moved with the times. Given that 30 percent of government employees are eligible to retire now, but haven’t, and maybe another 20 percent are within five years or less from retirement, we need a succession plan. Because, if those people walk, what happens to government?

“In this office, there are a number of us that are going to retire this year. We’re already down six positions because there were a number that retired last year and we haven’t filled those positions. And the way government works is, I need to leave and they need to pay off my vacation and everything before they can recruit to fill my position. So, there’s no institutional memory. The only institutional memory I’m going to leave behind is whatever I put down in policies and procedures. That’s scary. That means somebody else within the organization is going to have to do double duty at single pay until they can get somebody on board to fill my position. That’s not good business sense.”

5. THE AFFORDABLE HOUSING SHORTAGE WILL WORSEN.

The increasing poverty and infirmity of the elderly means many will eventually need affordable housing, probably with some social services. It won’t be easy to find. Although there is no complete inventory of affordable senior housing, it’s pretty clear there isn’t enough. Moreover, there’s not a lot on the horizon. That’s because, even though they’re sometimes easier to permit, the economics of senior housing projects still don’t work.

This April, Catholic Charities Hawaii broke ground on a 300-unit senior affordable housing project in Mililani, but it will probably take five years to build out, says president and CEO Jerry Rauckhorst. “It’s taken us three to four years just to put the funding together for the first 75 units – to get the tax credits and the Rental Housing Trust Fund money, and all the other pieces that had to be put together to make this work.” Clearly, even for an experienced agency like Catholic Charities, building new projects is an ordeal. And we’re going to need thousands of units to accommodate all those Boomers in the pipeline.

Even navigating the network of existing projects is often too much for many seniors, according to Diane Terada, director for community and senior services for Catholic Charities. “The affordable housing market has become extremely complex,” she says. “There are multiple housing management companies out there that manage housing projects and each has its own criteria for housing. Some look at things like criminal history and credit history. Some of them have minimum incomes that you have to have, and some have maximum income levels as well. So, there are all kinds of things that make it a particularly complex situation, particularly on Oahu, where there are a number of different kinds of housing projects.”

“Often, this is a multi-step process. Sometimes, because somebody is at risk or already homeless, we try to get them into whatever we can first, and then help them on a two- or three-step process before they find the final place they feel they can afford and they want to be in. The wait lists are really very long for these places, and have been for many years. They can run as long as five or six years for some of what they call the ‘30 percent’ projects, where you only pay 30 percent of your income for rent.” That includes all public senior affordable housing as well as some private projects.

In many cases, Terada says, it’s even a struggle to keep seniors in affordable housing once they’ve found it. “We do a lot of work with seniors who are in housing projects, and whose greatest risk is that they will get evicted or be forced to go into placement – because of care, like a nursing home or a care home – because it appears they’ve lost their ability to live in the community. We actually have case managers assigned to the different housing projects whose job is to help people stay in housing safely. Once you’re in senior affordable housing, generally you’re going to get inspected once a year and you have to re-verify your income on an annual basis. If you fail to do either one of those, then you place your housing at risk. So, the case managers help to ensure that the individuals are receiving the appropriate level of services so they can stay in that housing – whether that’s arranging for them to get chore services to come in, whether they need a public health nurse to come in periodically to monitor them, whether they need to be encouraged to go to the doctor, or to help them set up their records so they remember when they have to pay bills. All those kinds of things are critical. I think most of us take them for granted, but, for seniors, those are some of things that become the red flags that result in them having to go into a higher level of care and lose the ability to stay in the home they want to stay in.”

In many cases, Terada says, it’s even a struggle to keep seniors in affordable housing once they’ve found it. “We do a lot of work with seniors who are in housing projects, and whose greatest risk is that they will get evicted or be forced to go into placement – because of care, like a nursing home or a care home – because it appears they’ve lost their ability to live in the community. We actually have case managers assigned to the different housing projects whose job is to help people stay in housing safely. Once you’re in senior affordable housing, generally you’re going to get inspected once a year and you have to re-verify your income on an annual basis. If you fail to do either one of those, then you place your housing at risk. So, the case managers help to ensure that the individuals are receiving the appropriate level of services so they can stay in that housing – whether that’s arranging for them to get chore services to come in, whether they need a public health nurse to come in periodically to monitor them, whether they need to be encouraged to go to the doctor, or to help them set up their records so they remember when they have to pay bills. All those kinds of things are critical. I think most of us take them for granted, but, for seniors, those are some of things that become the red flags that result in them having to go into a higher level of care and lose the ability to stay in the home they want to stay in.”

Remember, all these programs provided by Catholic Charities, and by other aging service agencies, won’t cure the housing shortage; they merely treat the symptoms. As a state, we’re still left with this increasingly Hobbesian scenario where seniors compete against other seniors (and against the younger poor and infirm) for basic human necessities, like a home they can aord. And it turns out they’re going to need that home more than ever.

6. A GROWING PERCENTAGE OF SENIORS WILL LIVE AT HOME.

Most polls show that more than 90 percent of the elderly would prefer to stay in their own home as they age. They’re likely to get their wish – even if it kills them. All across the country, seniors are resorting to in-home care at least in part because they can’t afford the alternative. Neither they, nor the infrastructure of aging service providers, are prepared for the consequences of so many people getting old at the same time.

“In Hawaii, it’s even more acute because we have the greatest longevity in the country,” says AARP’s Stanton. “At the same time, Hawaii residents have low savings and a high cost of living. Also, as far as health services go, we’re really not prepared. That’s a problem because our community is really not ready for this huge increase in the 65 and older population. For example, we have only half as many nursing beds per capita as the national average. In fact, we have one of the highest occupancies in the country for nursing beds. If the nursing homes were hotels, having a 94 percent occupancy would be a delight; but, when you have a high 90 percent occupancy in nursing beds, that’s really full occupancy because you always have people moving in and out. So, what you find in Hawaii is that a lot of the burden falls on the unpaid family caregiver.”

The scale of the problem is startling, Stanton says, and it will only get worse.

“We have 247,000 unpaid family caregivers in Hawaii. If you paid them, that’s about $2 billion a year in economic value. If we didn’t have that safety net of family caregivers, then the whole support system would be in trouble. Of course, it’s difficult now, but without a lot of family caregivers the system would collapse.”

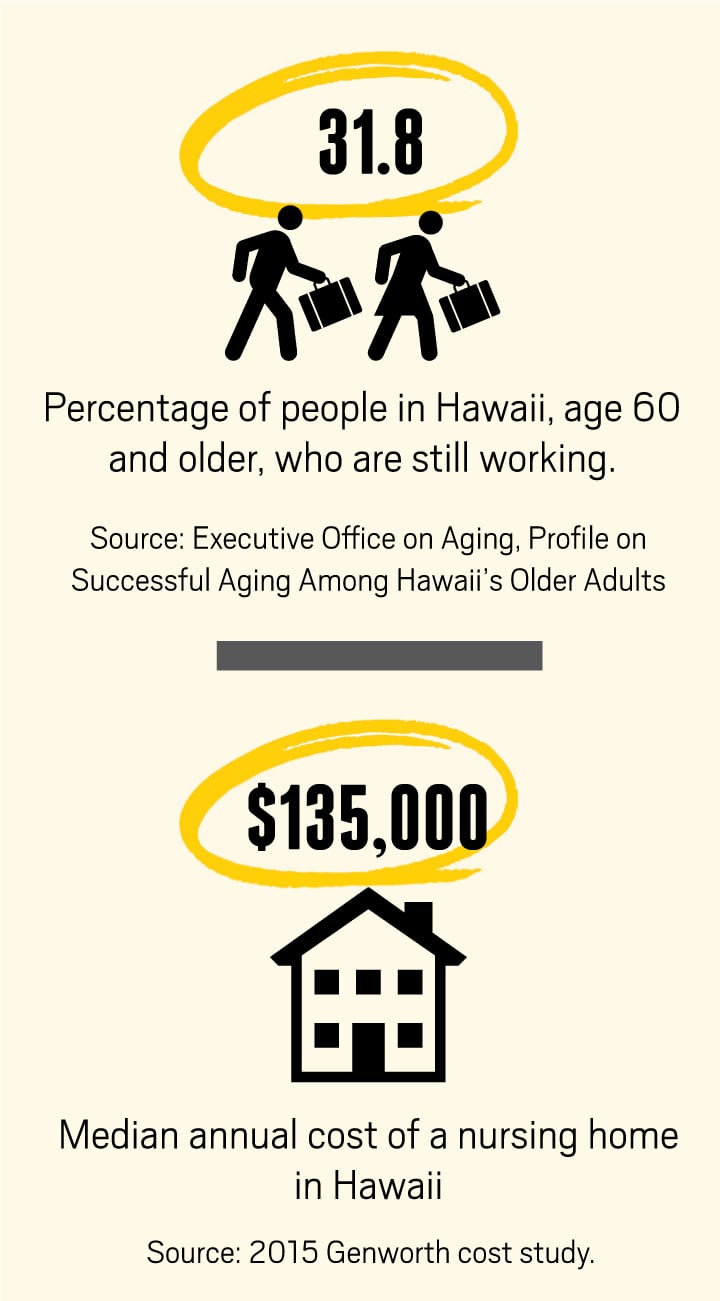

Even if the “system” doesn’t collapse, it has some troubling features. For example, the reliance on family caregivers generally means seniors end up caring for seniors. According to AARP, the typical caregiver in Hawaii is a 62-year-old married woman who’s caring for an elderly parent or her husband while still working full or part time. That means she’s trying to manage a loved one’s medication, provide wound care and perform the myriad sundry tasks necessary to keep that person safe and at home. At the same time, she’s juggling her responsibilities at work – maybe working fewer hours or even forced to leave the workforce prematurely. That’s a real price to pay for a woman approaching retirement herself. The lost wages and abbreviated careers of caregivers aren’t just inconveniences, they’re a real financial burden.

“Over a caregiver’s lifetime,” Stanton says, “those costs, on average, range from $283,714 for men, to $324,044 for women.”

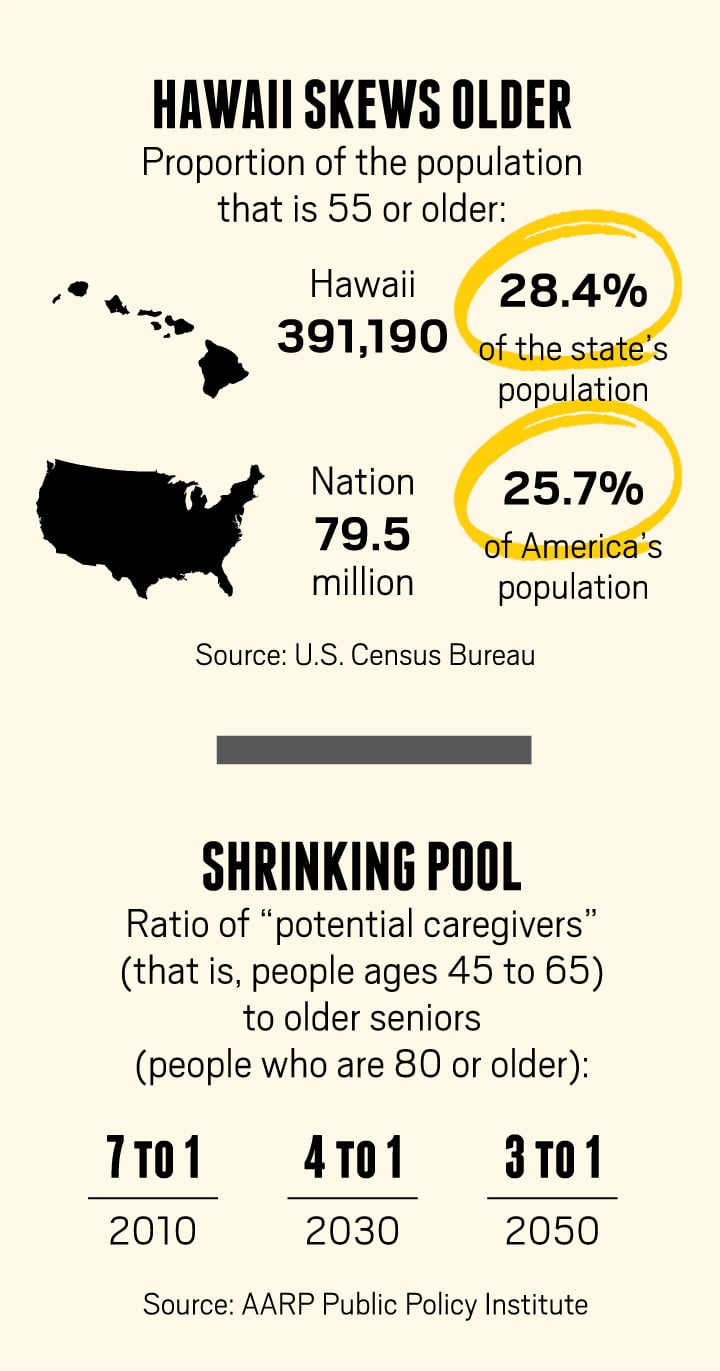

There’s another crisis brewing in the family caregiver system. As the Boomer generation ages, Stanton says, there will be relatively fewer younger people to serve as family caregivers. By about 2030, the population of people ages 65 or older in Hawaii will increase about 60 percent, Stanton says. Meanwhile, the number of potential caregivers – a group AARP defines generously as those ages 45 to 65 – will actually decline. According to an AARP Public Policy Institute report in 2013, nationally, there were seven potential caregivers for each person ages 80 or older in 2010. By 2030, that ratio will fall to 4 to 1. And because Hawaii’s population is older than the national average, the situation here will likely be worse.

Financially, though, there may be no alternative to our reliance on in-home care. The cost of institutional care has become prohibitive for most people. The median annual cost of a nursing home in Hawaii is $135,050, according to a 2015 cost of care survey conducted by the insurance company Genworth. Even assisted-living facilities, which offer a much lower level of care, cost $48,000 a year on average in Hawaii. At the same time, more than 35 percent of the state’s seniors rely on Social Security for more than 90 percent of their income. And, according to a 2013 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation, nearly 20 percent of Hawaii seniors live in poverty, earning less than the federal supplementary measure of $14,720 a year ($19,920 for a couple). Hiring a home health aide – with a median annual cost of $56,056 – is outside the budget of most seniors.

That leaves most of the burden on family members. AARP is pushing the state Legislature and the healthcare industry to recognize this reality by passing what it calls the CARE (Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable) Act. This law would require hospitals to record the name of the home caregiver when admitting a patient, and to notify the caregiver when the patient is moved or discharged. It also requires the hospital to provide basic instructions on tasks, like medication management and wound care, that the caretaker will perform at home. Although the CARE Act didn’t pass at the 2015 Legislature, similar laws are making their way through legislatures, red and blue, around the country.

7. SENIORS WILL HAVE A GREATER SAY IN THEIR OWN CARE.

As more service dollars for the elderly are directed toward in-home care, one consequence will likely be that seniors have more influence over how those dollars are spent. That’s partly because seniors prefer it that way, but mostly because of cost savings.

“CURRENTLY, THE AVERAGE PENSION IS ABOUT $25,000 A YEAR FOR A STATE AND COUNTY GOVERNMENT RETIREE. … CAN PEOPLE SURVIVE ON THAT TYPE OF PENSION INCOME LIVING IN HAWAII?”

–WESLEY MACHIDA

Director, State Department of Budget and Finance

“In the past,” says Stanton of AARP Hawaii, “the state used more of its Medicaid dollars for people in institutions. Something like 83 percent of the Medicaid dollars would go to institutions for people needing long-term care vs. about 17 percent for what we call home- and community-based services. Now, we believe Hawaii should be more like other states, where it’s 50/50, because the cost of caring for a person at home – up to a certain point, not if you need 24/7 care – is cheaper than in an institution. For a long period of time you can pay for the care for three people staying at home for the cost of one person in institutional care.”

The state is moving wholesale in this direction, preparing to fundamentally change the operation of the Aging and Disability Resource Centers – the frontline agencies coordinating the state’s long-term care services for seniors. “It’s turning the system on its head,” says Thompkins of the Executive Office on Aging. “The whole system used to be predicated on other people making decisions for seniors – about their healthcare, about where they lived, about what they needed and how they were going to get it. What we’re saying is that seniors can really make those decisions for themselves.”

The ADRC offices will still provide coaching for seniors and fiscal agents to actually handle the money, but the details of a senior’s care will be decided by that senior, Thompkins says. “Instead of the agencies deciding how many units of service you need – like: you need two baths a week, and you need five meals delivered, and you need this and you need that – we give the individual budgetary control to implement their own plan. They hire their own employees and decide what’s important to them to maintain themselves at home.”

She points out the increased efficiency in this system. “You might decide to pay someone $15 an hour, and that same person might help you bathe, make you meals and clean your house. The most anybody can hire somebody for is 19 hours a week, so maybe they’re there 10 hours a week and you pay them $150. For the same $150, if you go through the regular system, you’re going to get six hours of care. So you get more care in the new system. And, if you get more care, you’re probably happier.”

8. NONPROFITS WILL START CHARGING FOR SOME SERVICES.

Because of their limited resources, most agencies that serve seniors conduct a kind of triage. The neediest go to the top of the list and receive the most services. Relatively affluent seniors receive little or no assistance. The Executive Office on Aging would like to change that paradigm. Instead of turning people away based on income, they want the agencies that help seniors – including the county ADRCs – to serve everyone, but charge a fee for those who can afford to pay.

“How can we make our Aging and Disability Resource Centers self-sufficient?” Thompkins asks. She lists the services that the ADRCs currently provide for free, but that some seniors can afford to pay for: discharge planning from hospitals, transition of care from hospitals, case management and helping older adults come up with support plans. “All of those are things the staff at the ADRCs at the county and state level do,” she says. “They’re trained to do them, and they have certifications to do them. They could do them more if there was a revenue stream.”

This new philosophy takes its inspiration from “Scarcity or Abundance?” a 1998 essay by James Firman, the former president and CEO of the National Council on the Aging. In his reassessment of the modus operandi of aging-services agencies, Firman espouses a new approach to funding – one that no longer relies solely upon the Older Americans Act, Title XX or other forms of federal or state support. At the center of his philosophy of abundance is the idea that agencies shouldn’t just view themselves as providing free services for the indigent; they should also provide services to the financially secure. With this proviso: Those that can afford to should pay for these services.

Firman cites the example of a Meals-on-Wheels program in Mesa, Arizona. Like most home feeding programs, this one had a waiting list of three to four months because demand exceeded the organization’s budget. Then, Firman says, the executive director “switched to a system of charging people who have the means to pay for the meals.” Basically, clients at the Mesa Senior Center were given a choice: Wait three to four months for services, or pay full price and get served immediately. According to Firman, “Almost overnight, the center increased its client load by 15 percent. Since then, the private pay clients have asked for microwave-ready meals that can be used on weekends, thus leading to further innovation and service expansion.”

It’s not just individuals that Firman wants agencies to charge. He also believes insurers will become a source of abundance for aging-services organizations. For example, agencies can provide services that will help Medicare keep seniors out of hospitals and nursing homes. And Firman believes these agencies can charge Medicare for their services.

He writes: “If we were to succeed, over time, in channeling only 2 percent of Medicare funding for community-based services, within 10 years Medicare support of the aging network would be more than $8 billion – or four times the current funding level of the Older Americans Act.”

Nevertheless, Tompkins says, not all Hawaii agencies embrace the new philosophy. “If you look at the nonprofits in the state, the ones that get the biggest contracts, and you look at the forms where they report how much they get from government versus other sources, by and large, more than 93 percent of their revenue comes from government. That’s very limited thinking, because, if we get cuts, what’s going to happen to those businesses? They’re not going to have as much revenue. There are not going to be as many people served. They’re going to have to layoff people. It’s a very negative approach to not look for other places you could sell your product, because we have lots of people who can afford to buy their services. It’s not that there aren’t great disparities between older adults – because there are – but government services and funding were never intended to meet the needs of everyone. So, if you have resources, you’re almost obligated to take care of yourself, because there are plenty of people who can’t afford it at all, or can only afford to pay for very limited things. So, if you’re lucky enough to be able to pay, you should.

“Those people still need the services, though. They might still need home-delivered meals; they might still need transportation; they might still need case management or help with paying their bills or any number of things that we currently assist people with. But they can afford to pay for them. Why should they be at the top of the list just because they call in before somebody else?”

9. OLDER PEOPLE WILL TRANSFORM THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT.

In much the same manner that they helped create suburban sprawl, the Boomers are going to affect how communities look and work in the future. In some cases, that will happen naturally. For example, neighborhoods that already have a large population of seniors may gradually become what planners call “naturally occurring retirement communities.” As Terri Byers of the Executive Office on Aging points out, “This can allow us to develop innovative service delivery systems and strengthen relationships within the community.” She adds that aging can affect “how and where we organize medical care systems,” and may mean “an increase in multigenerational households.” In other words, as the Boomers age, Hawaii’s communities are going to look different than they do today.

Part of that is simply learning to accommodate the daily needs of older people.

“Nine out of 10 people over 65 say they want to stay at home as long as possible,” says Barbara Kim Stanton of AARP. “That’s why AARP is working with developers and home builders to make sure there’s universal design where the home is safe and comfortable for any age. We say, if it works for somebody who’s 80, it will work for somebody who’s 8.”

She points out that some developed countries have already done this. In the Netherlands, for example, multistory homes must have at least one bedroom and one bathroom at the ground level. Even in the U.S., it’s increasingly common for new homes to include features like grab rails, wheelchair ramps, and lower light switches and counters to accommodate older buyers. “You have to make them age friendly,” Stanton says. “And you’re going to see a trend – it’s already happening – in renovations to make homes age friendly.”

But, she notes, it’s not enough to just modify the home.

“As you get more infirm,” she says, “your world shrinks. Previously, you may have been able to travel the globe. Then, perhaps, you could travel to different states. Then, even within the state, you could go to the Neighbor Islands. But, as you get a lot older, especially if you’re not in good health, you become confined to a smaller and smaller area – whether it’s just your neighborhood, or your home, or, in the very end, perhaps just your bed. What we’re interested in doing is keeping seniors connected. We don’t just want them safe in their homes. We’re interested in making sure that the community and their neighborhoods are also age friendly.”

Toward that end, Stanton says, the AARP, the World Health Organization, and the City and County of Honolulu have launched a program called the Age Friendly Cities Initiative as a way to reconsider all the aspects of the built and social environment. “This talks about the changes that are needed in transportation, in housing, in open spaces, at the worksite, in social connectivity – like the Internet, in community activities and in volunteer opportunities. The idea is to see how we can make sure the community is age friendly so that seniors and their family members remain connected and vital parts of the community.”

In this, too, Hawaii is part of a larger trend, Stanton says. “When Mayor Caldwell committed to this, I think there were less than 20 age-friendly cities across the country. Now, I think, there are about 40 of these communities that are realizing they have to prepare for an older population.”

10. AGING BOOMERS WILL REMAIN THE SINGLE LARGEST MARKET FOR MANY BUSINESSES.

There is a silver lining to the silver revolution. Even as it becomes older and more feeble, the Boomer generation still represents a tremendous opportunity for businesses. Many of them may be poor, but collectively they’re the wealthiest generation in history and accomplished consumers.

“I like to say this is very much like the pig in the python,” says AARP’s Stanton, “because the Boomers have affected every part of the marketplace, whether it’s schools, colleges, the job market or what we purchase as consumers. For the most part, they control the buying power for the country, and also the state.”

She points out that, for all their problems, people over 50 still control the bulk of the wealth in the state. “Boomers and their elders accounted for almost 60 percent of all consumer spending in 2010,” she says. “I think we can safely say they’re the leading consumers in both the country and the state. Even though people don’t necessarily think of the Boomers as tech-savvy, one out of every two Boomers buys tech products annually, whether it’s smart phones, digital cameras, computers, tablets, e-readers or whatever. They make more trips to restaurants. Sixty-two percent of them buy new cars every fi ve years. Eighty percent of them purchase luxury travel. And, because they’re grandparents, they purchase 25 percent of all toys sold in the country. Of course, they also buy three fourths of all prescription drugs and more than 50 percent of all over-the-counter medication. So, we’re talking about a group of people with buying power, people who are not only looking at buying things for themselves; very often, they’re still looking out for family members, too.”

Stanton’s point, of course, is that, for all their problems, Boomers are still the largest market for the goods and services of Hawaii’s companies. For the savvy business owner who’s willing to learn what seniors want and fi gure out how to get it to them, that’s a lot of opportunity. Of course, most of those savvy business owners are Boomers themselves. In the immortal words of the old comic strip Pogo: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

A SENIOR PARADOX

WESLEY MACHIDA highlights a paradox for Hawaii’s seniors.

“Statistically speaking, if you work longer and retire at an older age, you live longer,” says the director of the state Department of Budget and Finance. “For example, if you work until you’re 70, your life expectancy is 89 years on average. But, if you retire at 55, your life expectancy is only about 82 years. So, you would live six to seven years longer if you worked to an older age.”

That means, on average, a 55-yearold retiree can expect to enjoy 27 years of retirement, versus just 19 years for the person who retires at age 70.

“I don’t know what’s worse,” Machida says, “living to an older age, but working longer; or spending more years in retirement, but dying younger.”