Nighthawks

![]() Honolulu at night is a different animal from its daylight self. Yes, it’s darker, but also emptier, the spaces less defined and much less colorful. What light there is feels dramatic; simple sights can feel staged.

Honolulu at night is a different animal from its daylight self. Yes, it’s darker, but also emptier, the spaces less defined and much less colorful. What light there is feels dramatic; simple sights can feel staged.

The person who works at night is also a different animal. The ones who have done it awhile can seem like variations on a theme. Many are quiet, interior, used to being alone for long hours. Not a few are immigrants far from home, scrubbing the tourist town for another day of showtime; or lifers who go home to make breakfast for their children and say “see ya” to the spouse who’s off to a day job.

Some are here by choice. Some stopped out of school and still haven’t made up their minds. Several got promoted into positions of greater responsibility, which turned out to be at night. Almost all shrug and say, “You get used to it.”

WHAT DON’T NIGHT SHIFTERS LIKE? THE SLEEP THEY LOSE.

What do they like about it? Having a job. Also, no traffic, easy parking, the off hours. For several, cooler temps. (If you miss wearing sweaters and jackets in Honolulu, come be a fashion plate on the graveyard shift.) To judge from the size of the boom boxes on loading docks, there’s something about escaping the prim restraints of an office supervisor who might object to “Hotel California” played with the volume turned to 11.

For some, the night is liberating. You can be yourself. In some jobs, you can even be bigger than life. Tow-truck drivers and EMTs alike are notorious adrenalin junkies – saving lives, separating wreckage, is a high. Like film noir actresses, night dispatchers cultivate voices of mystery, seduction, hard-boiled cynicism.

At night you can also feel your place in the universe. Don’t kid yourself, buddy – you really are an infinitesimal speck in the void.

What don’t night shifters like? The sleep they lose. The lack of a normal social life. Missing the spouse or partner, the kids. Statistics on night workers aren’t great: increased levels of high blood pressure, heart disease, depression.

And, yet, most we met on our journey through the night seemed well suited to their lives. Did they start out this way or did the night change them? Hard to tell. People adapt. Being around fewer people and being alone with your thoughts seems to be a recipe for introspection, so maybe night people come to understand themselves a little better than we distracted daytrippers.

Even the loudest night workplaces impart a sense of calm. A sense of community, too. Even the bleakest locations we visited had a feeling of ohana, as in the famous Edward Hopper painting of a diner at night, “Nighthawks,” a painting known by nearly every person we spoke to while setting up our shots.

Now it’s your turn. Tonight, as the clock ticks toward midnight and everything goes still, try killing the lights and turning off the screens. Settle into a soft chair with a single bulb overhead. Look at these photos. Just look. And, for a few minutes, imagine you’re a nighthawk, too.

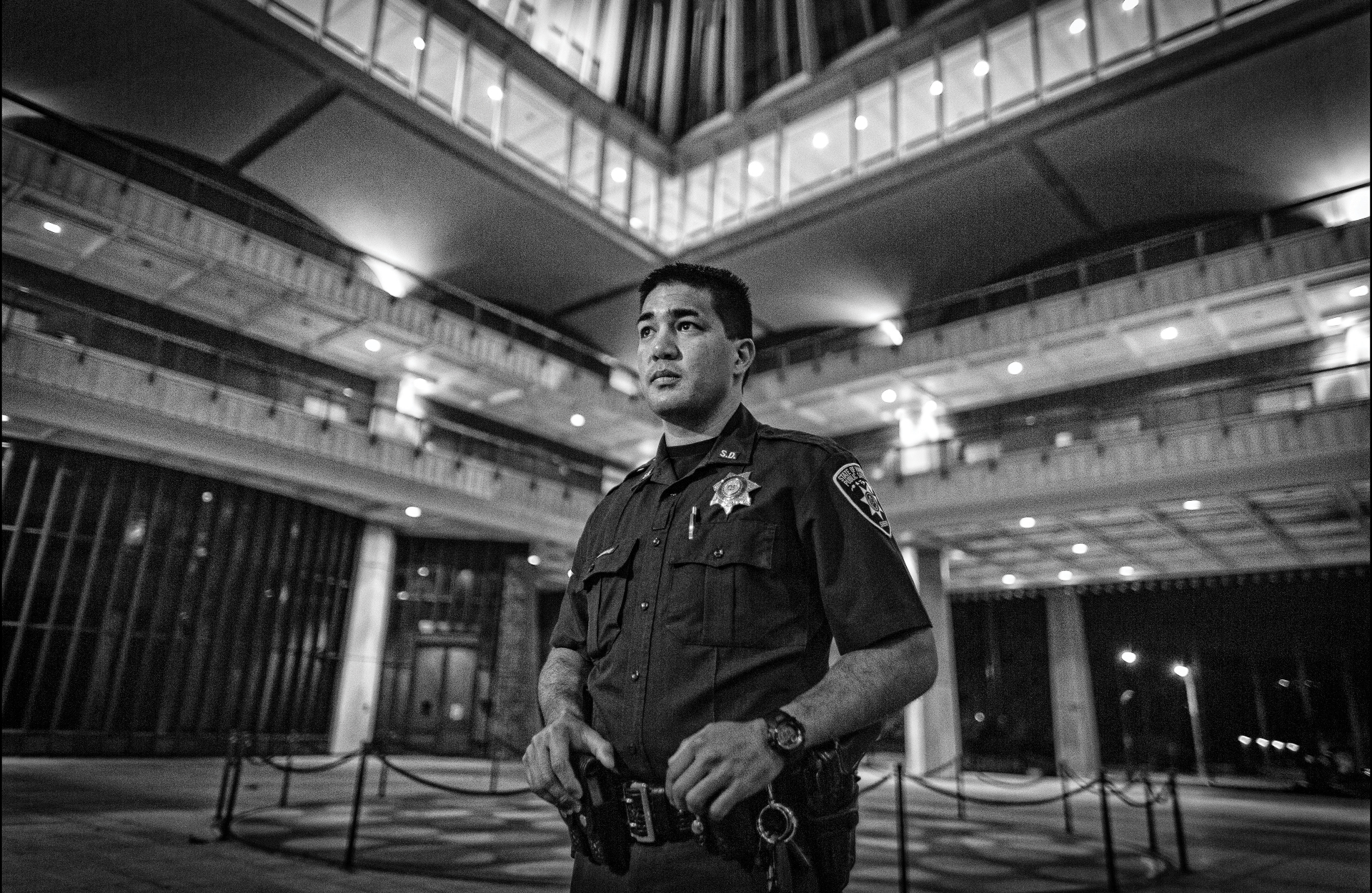

PEOPLE WHO WORK AT NIGHT ARE ON TIME. Deputy Blaise Ataboy stands, as promised, inside the open-air state Capitol building – his beat for the next three months. He’s only a few days into the new shift. “My sleep pattern is kinda off.”

It’s almost always quiet. Too quiet for Deputy Ataboy. “I like days. You get calls from all over the island.” To break the monotony, “sometimes we go out and make DUI arrests.”

We stand and comment about the Capitol architecture. “From what I understand, we’re one of two open capitols,” Ataboy says. “Built to look like a volcano, they say.”

A volcano that only erupts during the day, we joke.

IN WAIKIKI, THE TOURISTS ARE IN BED, Kalakaua Avenue is actually empty, except for the odd person sitting on a bench here and there – not homeless, but hooking up to Wi-Fi.

Inside the vast open-air atrium of the Sheraton Waikiki is pin-drop quiet. Through the buffed and polished marble floors we step out by the pool area. The grass-thatched drinks hut is closed for business, though open to the night air. We can smell the chlorine and hear the crump of waves against the seawall. The chaise lounges are perfectly arrayed on the mauka side of the pool, facing the sea, the dark and ceaselessly murmuring sea, beloved of poets and painters.

Magno, walks along the flagstones with a hose, spraying in steady sweeping strokes until every inch is clean. He moves slowly – to move fast would defeat his purpose – and keeps his eye on the plants, the edges, the steps. A wave smashes into the seawall and throws a shredded white sheet up into the air a couple of feet from his face. He doesn’t flinch. He knows the spot, the wave. He’s been doing this for four years.

Between the path and the hotel are wrought-iron braziers spouting flame. They’ve been cut in the shape of phoenixes, so, every few seconds, a firebird flares into sight, vanishes, then returns further down the line.

A step back to look up at the concave curve of the hotel affirms that every room is completely dark save one. This one, about midway up, is lit a bright Hopper yellow.

On the way back to Kalakaua, we pause in the atrium of the Royal Hawaiian Center to stare up at Jim, standing atop an arched escalator overhang like a Greek statue or a rock god. He doesn’t seem to grasp the dramatic possibilities, however, and ignores us, his hopeful fans below.

Broom in hand, he’s got a job to do.

DAY OR NIGHT, THE LEI STANDS at Honolulu International Airport are never crowded. But around closing time they really seem desolate, which makes it appear later than it is. You turn off the loop and slow down for what feels like an unintentionally humiliating ritual of mutual inspection. There’s the long row of identical open-air lei stands, each brightly lit to display the flower garlands on the walls; at each card table, the lei seller – often the lei-maker – sits before small piles of differently colored flowers. You crawl along trying not to look like you’re window shopping. The lei sellers often ignore the awkwardness and smile.

“WHEN YOU’RE DOING LEI FOR KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS YOU NEED A MORE UPPITY KIND OF LEI, NOT ORDINARY.”

—Dora laughs

My family always goes to the end in the belief that this is where the Hawaiians are. Who knows, really? But when the photographer and I ask one lei seller if she’d like to talk, she shakes her head and, sure enough, points to the end. “Talk to Dora. She’s Hawaiian.”

Dora smiles. She knows where to start a story and ignores our questions to pick her own thread and pattern. “My mother had this stand,” she says. “She retired when she was 90, she just made 93. You know, we all grew up with a needle in our hands, boys and girls.

“Mom did leis for the boats, the Lurline, the Aloha. My uncles and brothers used to dive for the coins, you know? I was meant to be here. My middle name is Leilani.

“My children all do leis, our specialty is traditional. My three sons, they all speak Hawaiian. Two sons help me with all my leis. Shiloh?”

A tall, quiet young man steps out of the back.

“My sons go into the mountains and do all my gathering when I do halau. When you’re doing lei for Kamehameha Schools you need a more uppity kind of lei, not ordinary.” She laughs.

But then she tells of how, almost every year, a student will come for a school project. “‘Auntie will you do this. Auntie will you show me for a report?’” Dora will make the seven or eight Hawaiian styles. “This one girl, she did a PowerPoint! And got an A plus.”

Dora will get home around half past midnight. She gets up at 4:30 to be on the road, “because I live on the West Side.” She stays inside the locked shop and sews. Business is slow for hours, and unpredictable. “Sometimes I won’t make a sale until one o’clock. Sometimes you sell 150 and have to ask the other stalls for help. Everybody pitches in, everybody here helps each other.”

It’s getting harder to find flowers, to get them at a good price. Plumeria that was a half-cent is now eight cents. People new to the Islands don’t let you gather flowers from their trees. The work is harder; when Dora was growing up, “we had 14 of us” sewing every day.

“My children, they don’t know if they’ll continue. We know rail is coming here, we hear this whole parking lot is going to be dislocated. But, you know, my feeling is, if you do good work, people will find you.”

Do you worry about Hawaii’s future? “I tell my sons, ‘Go into the mountains, breathe it all in, appreciate this kind of place. You have to appreciate it now.’ ”

I buy the last ginger lei. The photographer buys one with purple orchids.

SOMEWHERE AROUND THE WORLD, a First Hawaiian Bank customer who has lost a debit card or is having trouble charging a purchase has called this phone number and gotten Jina Gomes.

Or perhaps it’s a merchant checking on an account. Makes no difference. No matter who you are, where you are or what your time zone, Gomes, or one of her work mates, is there to take your call in an unmarked, nondescript building somewhere in Honolulu.

There are no windows, so Gomes has no view, but the walls are covered in frilly red hearts because Valentine’s Day is coming. Another consolation: The building is hurricane-proof.

Many of the calls are from Guam or Saipan. They tend to last two to three minutes. In between, she sips at a 40-ounce, heat-retaining container of coffee.

She’s been doing the job for 12 years and likes it. “I can do errands in the day and no traffic coming in or out.”

The only hitch: “Family and friends wonder why I don’t ever call back during ‘normal’ hours.” When her shift is done, around 8:30 a.m., she drives home to Ewa Beach, has breakfast and does housework to unwind. Bedtime is noon.

WE REV OUR CAR UP A STEEP ramp in a concrete neighborhood where Middle Street meets the freeway. Opening the doors and getting out, we’re swept into the embrace of a warm moist night redolent of cinnamon, yeast, sugar, wheat. The parking lot of Love’s Bakery is the biggest hot-bread hit I’ve ever had.

Inside, through glass windows, we peer into huge warehouse spaces. It’s like the ultimate hobby train layout in some nerdy uncle’s basement – there are tracks everywhere: on the floor, in the air, overhead, crisscrossing. Everywhere you look are loaves of nude, unbaked dough, loaves browned after a pass through the box-like steel ovens, loaves topped with bran and oat flakes after a second pass, toasted after a third.

In between the tracks are silos of flour, open bins the size of Dumpsters, filled with rising dough. Workers in flour-white shirts and pants scurry about and, yes, they wear white hats. (We wear plastic pullovers like shower caps.)

Production superintendent Dan Schaeffer is on call 24/7 and takes obvious pleasure in his domain despite being awakened for our visit. He lives only five minutes away, “so it’s not a problem.” And nights? “I love it. All that time to go to the bank during the day.”

The din rises as we enter the facility. Motes of flour dust in the air make everything a bit fuzzy and the smack of heat further clouds the senses. “You think this is hot, you should be here in the summer,” Schaeffer shouts. There’s no point in air conditioning – the yeast would stop working and the dough wouldn’t rise. “We have to have the heat and humidity, because this is all about speed – how fast we can make it. The trucks start coming at midnight. These will be in the market tomorrow.”

“I CAN WATCH BREAD BEING MADE FOR HOURS.”

—Dan Schaeffer, production superintendent, Love’s Bakery

He gestures at a conveyor belt humming and shaking, like a river at flood. “Is this Roman Meal?” we shout. In our opinion, the man who doesn’t thrill to Roman Meal and its logo of a Legionnaire standing with his sword at ready is tired of life. When Schaeffer says, “Yes!” we feel a childlike joy. “Split-top right now,” he adds. “It was the first wheat bread.”

Schaeffer is not tired of life. “I’ve been in bread since 1989,” he shouts. Originally from Indiana, he started at Harlan Bakeries in Indianapolis. He walks us past the mixers churning hundreds of pounds of flour, water, liquid sugar, enzymes. From there the dough goes into a hopper that pops out 16-, 24-, and 32-ounce balls.

The balls are cut, pressed to squeeze out the air, lightly floured, then left for three minutes to relax. Not Schaeffer: At several bends in the catwalk, he spots trouble on the tracks, bottlenecks such as loaves stacking up or tins of dough jamming the entrance of an oven. Moving around above workers as they scramble up into the rigging to straighten things out, he shouts, gestures, directs traffic.

We climb metal stairs and come upon a worker gently scattering handfuls of bran and oats on passing loaves. Virgilio radiates the placidity of a retired godfather feeding pigeons in the park. It turns out he was a foreman for 22 years and then bid for this calmer roost. For the past two years he’s been doing quality control, making sure those honey oat bran loaves get their toppings. Smiling, he makes no effort to talk above the rattle and hum.

“From here on it gets boring,” shouts Schaeffer, as we step into the quiet of the stairs down to the loading docks. “I can watch bread being made for hours.”

We can, too.

THE HONOLULU FISH AUCTION AT PIER 38 is now such a tourist attraction you can even sign up for a tour. It’s the only fish auction between Tokyo and Maine, drawing buyers for top sushi chefs and four-star restaurants, as well as those from our local stores and poke shops.

But the bell to start the auction rings at 5:30 a.m. and that’s morning to most people. So we go at 1 a.m., when the off-loading from the fishing boats begins.

To this, the public is not invited. Instead of the milling crowd of intense buyers eyeing sample cuts of bigeye and bluefin that makes the auction a spectacle, the scene here is somnolent, the big shed empty when we arrive.

Out front a man sits in a battered office chair. Inside, a man wearing a fluorescent yellow safety vest over a down jacket fiddles at a computer. At the end of the pier, a double row of fishing boats rafted up to each other rise and fall like heavy sleepers. Even a brindle cat that approaches out of the darkness stops a good 20 yards from the shed doors.

Here and there someone steps on or off a boat. They’ve been out to sea for an average of 22 days, but, if there are any dazed celebrants of shore leave on board, we’re not seeing them.

The man in the chair stirs. Pele Jr. came here from Western Samoa in 1988. Back home he was a bricklayer. Here? “I lay out the fish.” He doesn’t miss his old trade.

“When I first came I worked construction, but, you know, the sun too hot. Here, it’s cool at night. Here, they give you extra hour. You can get overtime. Good pension plan. Go home at six, sleep, don’t have to be back until 11:30 at night.”

Over on the boat Capt Millions, fishermen walk a boom over a center hatch and lower a clanking chain into the hold. A tug, a grinding of steel links through block and tackle – and here comes a trio of tuna trussed by their tails. Jerk by jerk they rise into the air, are swung over and gently lowered into a wheeled steel cart. Time and again the action is repeated; at the end, a net crammed with mahimahi is withdrawn and laid down.

Pele Jr. and Pula, another worker from Samoa, go inside and get ready. The shed doors are opened. A forklift brings the cart over and tilts it so the fish will slide easily when tugged with the gaff. It’s 1:11 a.m.

The work is smooth and unhurried. There are about a dozen men and nobody is talking. They move slowly up to the fish, one at a time, selecting one or two to shift, always taking care. The fish are gold, so, to avoid bruising the flesh, Pele Jr. and the others slip their gaffs under a bony lip or hook the tip of the tail. Then, like a dancer leading a pas de deux, one man prods each big fish into making a last leap – onto the rubber mat in front of the United Fisheries man at the computer, who issues a tag for each fish after it has been weighed and its quality assessed. Finally, Pele Jr. and the others roll the fish off in carts to certain stations in the still-empty, 48-degree shed, where they’re partially covered in ice.

At 1:34 the bin from Capt Millions is empty. “Yesterday we did 100,000 pounds of fish,” says Pele Jr., when the last of the mahimahi are laid on the rubber mat. He’ll make up boxes after the auction to ship to the Mainland, to Japan. Sometimes he’ll fill containers. But the nine 200-pound tuna, biggest of the lot, get their own cart and bed of ice.

The shed doors come down. Slowly, the men drift toward the end of the pier and sit on the edge of the dock, backs to the boats and the sea. A second bin arrives. The shed doors come up. The men are already up, in motion, walking in ones and twos across the darkened lot, not talking. At the door they pick up their gaffs and wait, holding them so casually they seem like extensions of their arms.

Tonight’s haul will be 87,000 pounds. There will be no overtime.

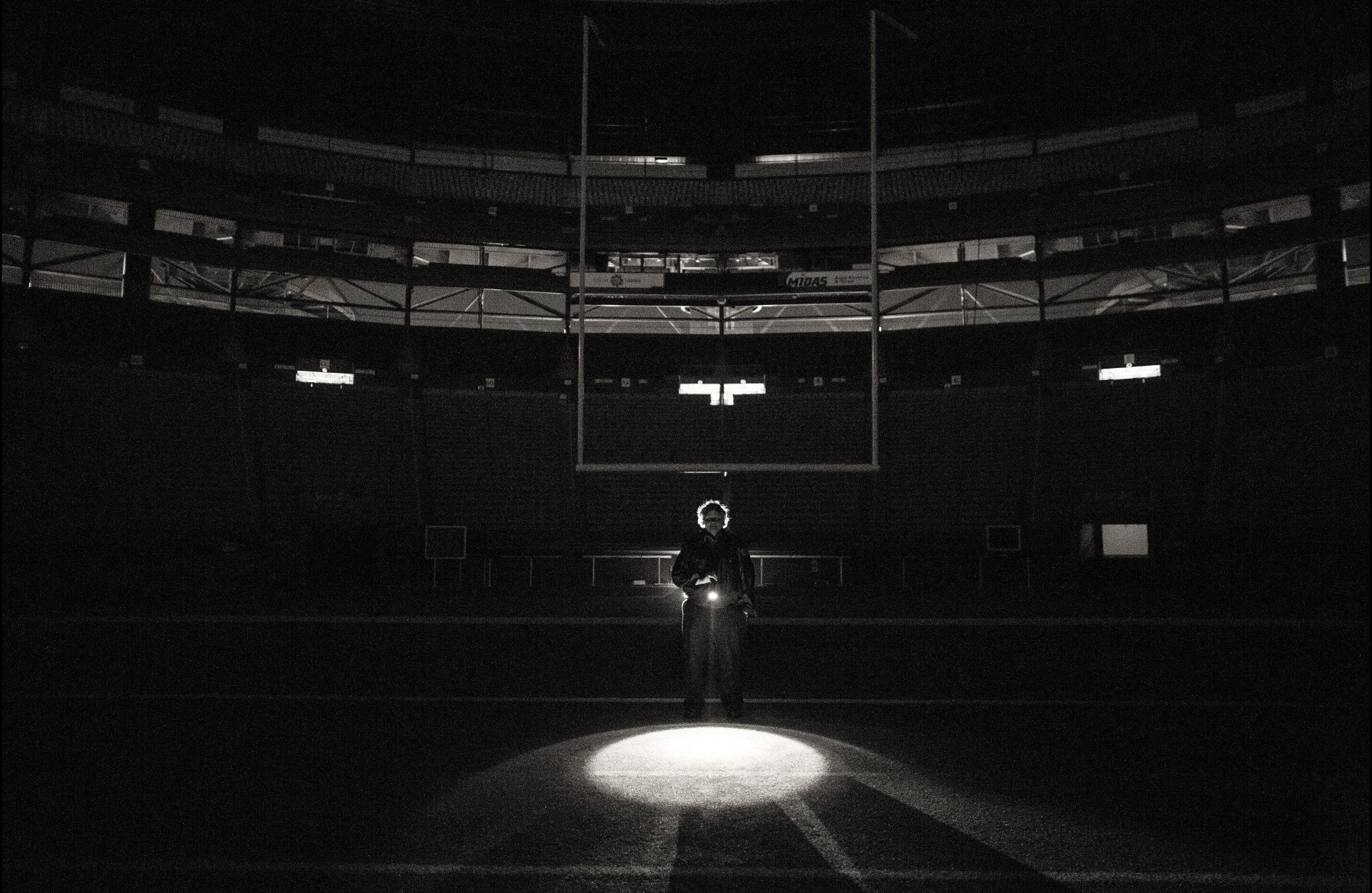

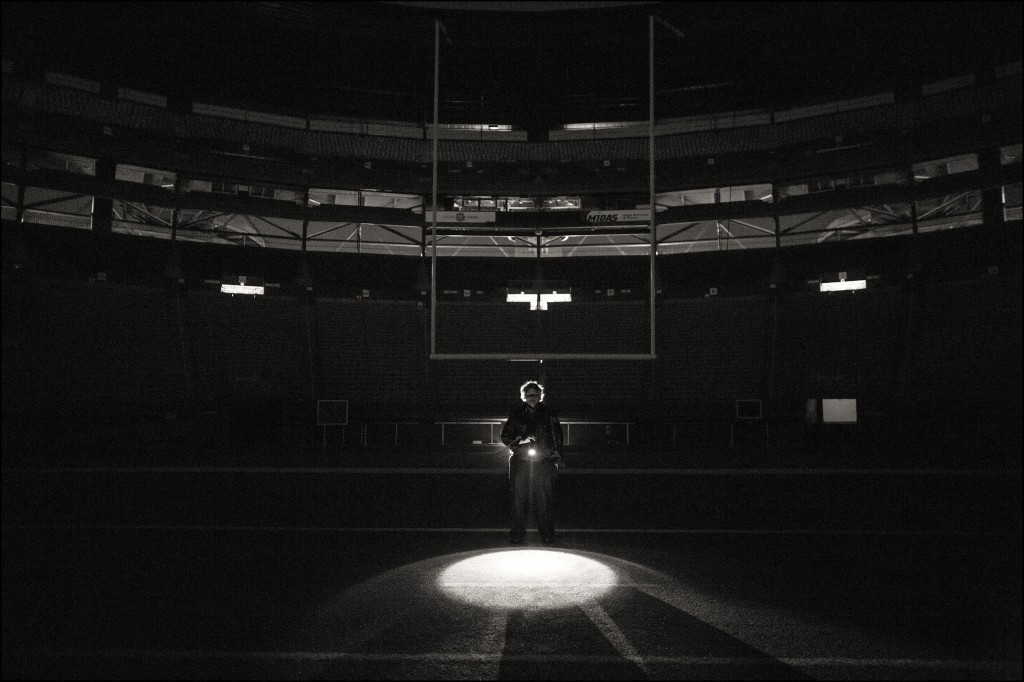

STANDING ON THE CROWN of the field at Aloha Stadium in the middle of one of her rounds as chief of night security, Ruth- Ann likes to think of all the Pro Bowls played there. “Think of the players,” she says.

You listen in the dark to the spare details of a life of a self-made woman: 13 years in the Air Force military police, guarding nuclear-missile silos in Montana. After her discharge she took a job with a security firm in Hawaii for a year, strictly for the sunshine. Then this one made her a better offer. Very quickly she found herself promoted – out of the sun.

I can see why. Ruth-Ann’s six-foot-one and unmistakably in charge, yet there’s a peaceful, unruffled quality about her. I feel secure in her presence – not intimidated.

“YOU’LL SEE MORE STARS HERE THAN ANYPLACE ON OAHU.”

—Ruth-Ann, Aloha Stadium

As most guys might, I dig my toes into the artificial turf, make a quick juke when she isn’t looking, relive the sports career that might’ve been had I skipped the rock music clubs, made it to the weight room more often. I coulda been one star!

“Look up,” she commands. “You’ll see more stars here than anyplace on Oahu. The stands block out the lights.”

She’s right. The starry night is breathtakingly clear and full of galaxies far away. And I didn’t have the size, or the speed, anyway.

“I love this stadium,” she says.

IN INKY BLACK SUBURBIA, we almost miss the large Kapolei printing plant of the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, but soon we’re picking our way carefully through tall, clattery rooms, watching out for the herky-jerky dance of approaching robots.

Overhead, color inserts fly in looping tracks that twist just like a Mobius Strip; another line spins off USA Today, the Sunday Money section of the Star-Advertiser and, soon, The Garden Island, Kauai’s daily paper. This location used to print The Honolulu Advertiser and the Honolulu Weekly, too – the secret of printing plants, like bakeries, is that they’re the source of many different incarnations, home to off-label versions, even rivals. In a printing plant, all papers are brothers under the skin.

As are newspaper workers. The man with most seniority here is Zachary Naone, who we come across in a former forest – giant tan rolls of newsprint – trimming the outer layers so each roll will feed smoothly into the presses.

Zack has 49 years combined on the night shift at the merged dailies. “We call him Father Time,” says John Sanchez, the assistant pressroom manager and our guide to this underworld.

“Daylight?” echoes Zack, silver-haired but youthful in a dapper, after-dark Count Dracula way. “Don’t miss it. Gives me more time to get my business done.”

He comes home around 3:30 a.m., has a couple of cups of coffee, and watches television until his wife wakes up. They have breakfast. Every three months or so they go to Las Vegas. There are no adjustment issues. “Inside the casinos, you can’t tell if it’s day or night anyway – no clocks,” he says.

The Kapolei plant is 10 years old, which makes it “state of the art,” says Sanchez. “It only takes five men to run all this.” Zach can remember the old days of hot-type presses with the news composed on lead plates that weighed 35 pounds per page. “There would be 12 guys on the presses 25 years ago,” he said. “Now there’s one.”

IT’S 4:30A.M. WHEN, one by one, the line chefs slide through the back door of the Koko Head Café in Kaimuki, one of Honolulu’s hottest new restaurants. Inside, the kitchen space is small, a cage made of bright, perforated stainless steel.

It’s quiet. There’s no music, no loud or extended conversation, no haste, but no wasted effort, either. The workers keep their elbows tight and their heads down, their movements economical, choreographed, like fighters in a clinch. And, indeed, star chef Lee Anne Wong is in New York City right now, filming an episode of “Chopped,” a reality TV show that places cooks under intense pressure to … cook. (What else did you expect?)

The frivolous thing in sight is an action figure from “Rocky”: Apollo Creed, wearing those gaudy American flag shorts.

Fight metaphors aside, the mood is upbeat and unhurried. Sous chef Clark Neubold wears his authority lightly. From snowy Connecticut, Clark has been doing food for 10 years. “My wife has an uncle from Hawaii. My knees were too messed up to snowboard and I couldn’t play hockey, so I thought I’d give this a try” is how he puts it. Been here a year. Likes it. Hikes in his spare time.

A foot away, Franco Gatto Bellora in the rising-sun do-rag oversees Kim Beccaria the newbie. He formerly worked as a photographer. She was a prosecutor, she says. Hearing this, nobody bats an eye. Food draws refugees from every occupation. Kim’s reasons could be anyone’s: “I just like working with food. It’s fun.”

But there is an element of performance, of pressure – there’s a reason Apollo Creed is their patron saint. Franco makes five pots of pancake batter for the opening rush. After that, “We make it fresh every five or six orders.” Looking over Kim’s shoulder as she cuts, he says, “Try to cut less.” Profit margins are razor-thin, so are recipes. “With parsley and vinegar, we don’t use olive oil to bulk it up, but sunflower oil.” Kim’s eyes open wide. “Secret!” He nods.

Franco takes down a copy of Wong’s new cookbook, “Dumplings All Day,” and checks a recipe. Clark unwraps his knives. Putting herbs and ingredients into a blender, he pulses, decants into ramekins. The line chefs with their backs to us slide pans on and off burners. The smells start to build, incomplete tastes of dishes to come.

5:45 a.m. Clark eyes the day’s market ingredients: “21 monchong,” he calls out.

“I had a nightmare that everything was going wrong and it was all my fault,” says Kim.

“The fear,” someone says. Michael says: “It’ll happen.” The team choruses: “It’ll happen.”

Sarah Barnes-Kato, the manager, enters through the front door. The front room staff starts arriving, wiping down tables, laying places. Clark runs through the morning’s menu, the special cocktails for Valentine’s Day: Lover’s Lemonade, The Cupid Colata. Franco makes a smoothie out of papaya and places it on the counter. Someone else sets down a plate piled with hash browns and crisped bits of bacon. But nobody tries anything – the pace is picking up. The menu come down and get rewritten as the staff meeting takes place. “Broccoli Cheddar Kim Chee Biscuits? Beef and kale?”

6:48, the first Japanese tourists arrive in a taxi. High fives for the line cook who guessed right. 6:51 the staff meal starts. There’s still no sense of haste. The tourists outside take selfies in front of the café, then pictures of the staff inside.

Clark raises his voice for the first time: “Everybody ready?”

Nods and murmurs of assent. “Dumplings OK?” he asks.

“Terrible!” Laughter.

“I love our pancakes!” A server’s rallying cry. Overhead, Jack Johnson’s voices, “Let’s rewind.”

The line outside is up to three when the clock strikes seven. Sarah opens the door and welcomes the first customers, escorts them to a table. The cell phones are out and taking pictures before the menus are opened.

Breakfast is served.