6 Great Small Nonprofits and What Makes Them Succeed

Hanahauoli School

The first rule of not-for-profits,” writes nonprofit consultant Peter Brinckerhoff, “is mission, mission, and more mission.” Mission, he points out, is a nonprofit organization’s legal reason for existence. It’s why the staff works long hours, often for a fraction of what they would earn in the for-profit sector. It’s what attracts volunteers and donors. This is why it’s so critical to have a well-defined mission that everyone in the organization knows and is passionate about.

“I would say the nonprofit organization that lives and breathes its mission better than any other that I’ve experienced is a little private school called Hanahauoli School,” says Terry George, COO of the Harold K. L. Castle Foundation. “I admit my bias. I’m a parent of two kids who go to school there, and the school is a grantee of the foundation, but their mission has really stood the test of time.”

The key to that longevity, George says, is that the school makes the mission the centerpiece of what it does, not an afterthought. “Their board starts every meeting by having someone read the mission aloud. They really review it. Every employee there knows what the mission is. And they live it.”

Hanahauoli School’s mission statement is a long, eloquent defense of the educational philosophy of John Dewey. It champions an experiential approach to education, one in which children learn by doing and develop at their own pace. That may seem abstract, but it’s reflected in everything the school does.

“I think our mission really does guide our decision-making,” says Bob Peters, Hanahauoli’s longtime head of school. He points to the school’s decision to use multi-age class structures, merging kindergarten and first grade, second grade with third grade, and fourth with fifth. “We recognized that children don’t develop equally across all areas at the same pace. Once we went to multi-age, it allowed us to give those youngsters who needed a little bit more time the opportunity to do that, and those younger kids who were ready for greater challenges to have that happen at the same time.”

Mission is also about what not to do. In the past, Hanahauoli has considered expanding or adding a middle school. “After some serious study,” Peters says, “the board really felt that we were looking at young children. That was the focus of our philosophy, and remaining an elementary school was much more consistent with and well-aligned with our mission.”

Bias toward marketing

HUGS (Help, understanding & Group support)

As Peter Brinckerhoff points out, nonprofits need to “understand that everything they do is marketing, and see that every act, from service selection to how the phone is answered, is a marketing opportunity to pursue their mission.” One organization that embraces this holistic approach to marketing is HUGS, a small nonprofit that provides support services to the families of critically ill children (171 families at last count). The result is a level of sophistication that makes the organization seem much larger than it is.

Case in point: When Nordstrom’s department store decided to use its grand opening at Ala Moana Center in 2008 as a fundraiser for local nonprofits, they selected just three organizations from dozens of applications. Two slots went to large, well-known organizations – Bishop Museum and the Boys & Girls Club – that had the resources to make elaborate proposals. The third went to tiny HUGS. What was the secret? Marketing top to bottom.

HUGS executive director Donna Witsell says the first step to this comprehensive approach to marketing is to hire well. “Part of it is you start with people that are passionate about what you do. They really, really have a passionate belief in the mission of the organization. All of us know the well being of the families that we serve depends on what we do. If you put that at the top, everything else falls into place quite neatly – most days.”

That’s critical for a nonprofit, because everybody in the organization is part of the marketing team, whether they know it or not. With HUGS, it starts at the top. “Our board development committee has been going out and targeting certain sectors,” Witsell says. “They’ve been incredibly successful in cultivating new members, in bringing in people to nominate who have brought such gifts to the organization.” That’s marketing.

Witsell believes the same level of professionalism colors everything HUGS does. “Every part of our constituency should be able to be a mouthpiece for the organization. That’s why, when we’re out in public, our presentations are as professional as they can be. You’re an ambassador, a reflection of your organization.”

Witsell says HUGS has set some basic responsibilities for itself and its employees that have to be met. “We make sure when we show up at an event like a golf tournament that our presentation is professional and that it illustrates our appreciation for them. We have smiling faces, and everyone is in their HUGS shirts thanking people and greeting people.” She says it’s also important to have some of the organization’s beneficiaries there. “When your beneficiaries are able to say to your sponsors, ‘Thanks for what your organization does for me,’ that’s powerful.”

Assets-based approach

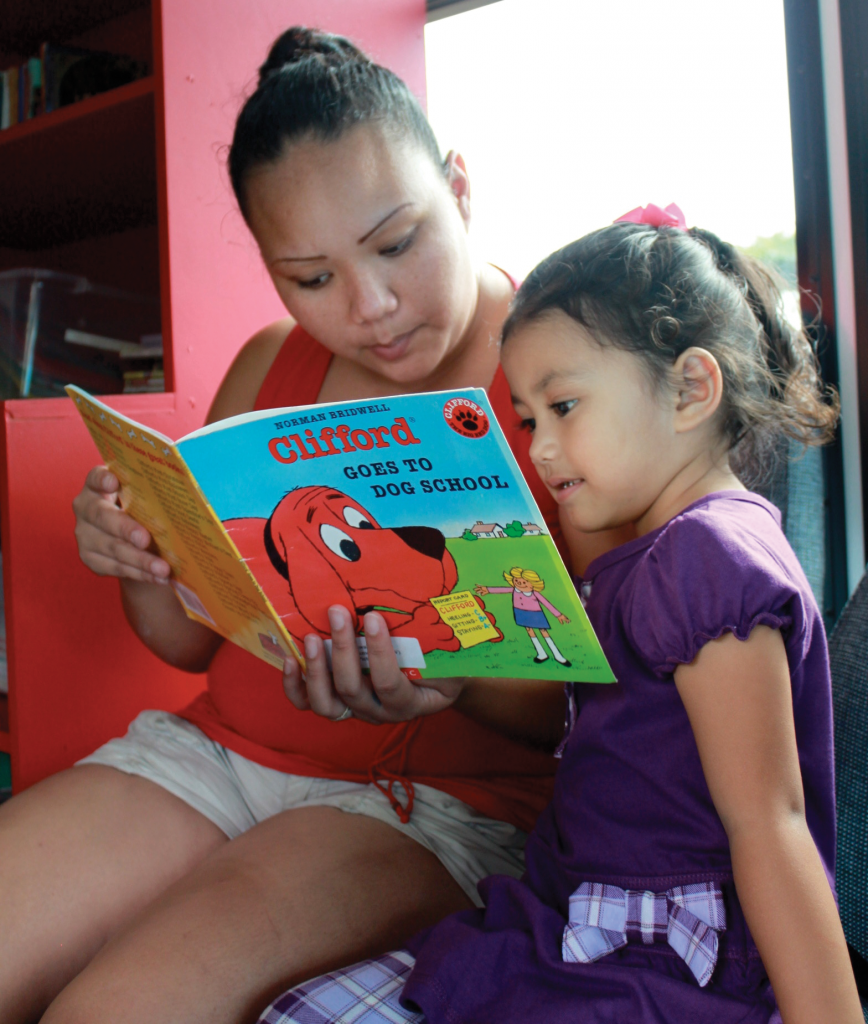

Hawaii Literacy

All too often, one of the unintended consequences of charity is that the people a nonprofit serves become dependent on those services rather than empowered by them. An assets-based approach to community service tries to avoid this pitfall by emphasizing clients’ strengths instead of their weaknesses. This strategy, while increasingly popular on the mainland, is still uncommon in Hawaii. One local agency that stresses an assets-based approach is Hawaii Literacy, a nonprofit dedicated to ensuring people of all ages can read and write.

Suzanne Skjold, executive director, uses the organization’s youth program as an example. Hawaii Literacy lets the children choose projects and how to implement them. Because the organization doesn’t emphasize their weaknesses, their strengths shine through. Older kids help younger ones. Poor kids work side by side with those who aren’t. (Hawaii Literacy doesn’t restrict its services to the poor.) All take ownership in the program.

Holly Henderson of the Weinberg Fellows, a program that trains nonprofit leaders, says this approach yields more than just literacy. “It’s doing leadership development by involving the kids in planning and executing the program. It’s also unobtrusively building relationships and changing attitudes, because both have and have-not kids are working together, leveling the playing field. And it’s helping to build the next generation of volunteers.” All that simply from recognizing the strengths inherent in children and encouraging them to act.

It’s harder than it sounds. “The first thing we do,” says Skjold, “is determine whether they can read and write.” In other words, Hawaii Literacy, like most social services, begins by highlighting a weakness instead of a strength. The difficulties mount from there. “Part of the problem is the way we get our funding,” she says. “Often, we have to tell potential funders something like, ‘Please help this poor, illiterate child.’ We seldom get to focus on that child’s strengths. We don’t get to say, ‘This is a kid who really has potential and great intelligence and could one day grow up to be a doctor.’” These are problems shared by most nonprofits that want to take an assets-based approach.

But Skjold believes that striving toward an assets-based approach makes Hawaii Literacy a better organization and its programs more relevant. “All our programs are very driven by feedback that we get back from our clients,” Skjold says. “We ask them, ‘What do you want this program to be? What are we not doing that you think we should?’ ” In other words, by recognizing the clients’ strengths rather than weaknesses, Hawaii Literacy helps break the cycle of dependency. “They truly have the ability to help with the direction of the services that we provide.”

Enthusiasm for collaboration

Learning Disabilities Association of Hawaii

Liz Chun, longtime executive director of Good Beginnings Alliance (another of our six best nonprofits), says the trick to nonprofit success is to find your niche. Of course, that’s another way of saying, stick to your mission. The flip side, especially for small nonprofits, is that you have to acknowledge what you’re not good at – even when those deficiencies directly affect your programs. Frequently, the answer to this conundrum is to collaborate and develop partnerships – with other nonprofits, government agencies or individuals. One agency that has embraced this is the Learning Disabilities Association of Hawaii, a nonprofit that enhances the education, work and life opportunities of disabled youth.

LDAH executive director Michael Moore, who recently attended the Weinberg Fellows training program for nonprofit leaders, talks about being receptive to collaboration. “I was surrounded by 13 other people who, to one degree or another, this organization was associated with,” Moore says. Some, he saw, were from organizations LDAH had worked with in the past. Others, like the director from Project Vision Hawaii, he recognized as obvious partner candidates for LDAH’s ambitious school readiness project. Even before finishing the Weinberg program, Moore began reaching out to his peers. What followed was a flurry of emails as organizations explored opportunities to partner. “I think that really touched Holly,” Moore says, “because that’s kind of what they want: to see people talk to each other, to figure out how to get together and provide a service that reaches more people.”

The best example of LDAH’s collaboration is its School Readiness Program, a comprehensive effort to provide Hawaii preschoolers with development, socioemotional, vision and hearing screenings. The program is an impressive exercise in partnership and planning. Some of the participating agencies include the Center on Disability Studies, Hale Naau Pono, Waianae Neighborhood Place, PATCH, Keiki o ka Aina, InPeace, the Community Children’s Council Office and several others. Little LDAH’s ambitious program also received significant funding from the Aloha United Way, an endorsement not without controversy in the nonprofit sector.

But Moore believes the School Readiness Program succeeds precisely because it is ambitious. “I think the reason we won is because, while everybody else was writing and frantic to get their application in in a relatively short period of time and wrote proposals for $10,000, $20,000, or $70,000, I spent all my time making calls and identifying my partners before putting pen to paper.”

The final budget for the School Readiness Program was more than $500,000, most of which gets passed on to LDAH’s partners.

Advocacy

Good Beginnings Alliance

At some point, it’s not enough to feed the hungry; you have to deal with poverty. Or you tire of measuring the decline in fish populations and start to think about banning gill nets or regulating nonpoint source pollution. In other words, programs only go so far; to really change things, nonprofits have to affect policy. They must be advocates.

Good Beginnings Alliance has long advocated for early-childhood education and health. “Actually, our organization was set up originally in the Legislature to work with the governor’s cabinet leaders,” says Liz Chun, who has served as executive director since GBA was founded in 1997. “We were an intermediary created to help coordinate the early-childhood education system.”

Although GBA has occasionally managed programs, that has never been its primary mission. Its real purpose is to educate the public, legislators and government officials about the importance of helping children from birth to fifth grade. Its real purpose is to track the policies and trends that affect young children. Its real purpose is to drum up support in the community for programs that improve their health and prepare them for an education. Its real purpose is to advocate for young kids.

A recent example of this kind of advocacy has been the Be My Voice Hawaii campaign, which GBA launched in response to dramatic cuts in the state budget – cuts it feels disproportionately affect young children. Be My Voice Hawaii is intended to give the public a way to let legislators know what they think about children’s issues. “It’s a way they can say they believe that more resources should go to children,” Chun says. “We’re selling an investment in early childhood. We want more people to understand that if they want this to be a state that prioritizes children, they have to let legislators know it.”

That’s not a mission teachers or child services organizations can do effectively. But all nonprofits should be thinking about advocacy. “So, if you’re a nonprofit that deals with helping homeless families,” Chun says, “you need to be aware of the policy issues that impact that. For some, it’s probably connecting with those whose main focus is advocacy. They should be part of an organization that will do that for them.”

Community-based organization

North Kohala Community Resource Center

Closely aligned with the ideas of collaboration and assets-based nonprofit management are community-based organizations like the North Kohala Community Resource Center, whose mission is “to increase the number of successful community-improvement projects by providing local support and education as well as bridges to funding.” In other words, community members think up projects and programs that will help the community, and NKCRC serves as a fiscal sponsor, helping them develop the resources and funding to execute those plans.

At its heart, community-based development is more of a network than a pyramid. Solutions don’t trickle down from experts or authorities, they well up from countless sources in the community. Bob Agres, executive director of the Hawaii Association of Community Based Economic Development, compares these networks to mycelium: Projects mushroom up where they’re needed, but the real structure is hidden from view. So it is with NKCRC: Its two-person staff belies a vast system of community organization. “At the current count,” says founder and treasurer Bob Martin, “we have 68 or 69 projects that we’re supporting.” Over the past 10 years, the organization has funneled more than $7.5 million in nonprofit support through the community.

In many ways, selecting NKCRC as a best nonprofit is cheating. As an agency whose mission is to serve as a fiscal sponsor and general enabler of other organizations, NKCRC can be thought of as a stand-in for the dozens of projects they support and the people behind them. But that’s exactly the point. The success of NKCRC is the quintessential bottom-up, self-organizing body that is community-based development.

According to Agres, an excellent example of this kind of collaborative, community-based project is a new program called Community Harvest. This project encourages the community to collect all the regional produce that would normally fall and rot, and gather once a month to can, preserve and smoke it. The volunteers consume some themselves, but most they give to the food bank. “It’s like going back to plantation days,” Agres says, when the community prepared and ate food together.

Although NKCRC is technically the fiscal sponsor of Community Harvest, it’s really the brainchild of an energetic young businesswoman named Angela Dean, who runs the Kohala Intergenerational Center, and David Fuertes of Ke Hana Noeau. Earlier this year, the program became one of five winners of the Hawaii Community Foundation’s Island Innovation Grant, securing $82,000 in funding.

Fostering these community projects makes NKCRC popular. “We only have about 1,800 households in North Kohala,” says Martin. “About 300 or 400 of them give to us every year. Probably even more donate to some of our projects. That’s because the community can see the benefit of having a resource center.”

How We Picked Them

When we set out to identify great nonprofits in Hawaii, we knew we should not rank their missions. All the agencies on this list serve critical roles in the community, but so do dozens of other nonprofits. It’s pointless to decide if feeding the poor is more important than teaching children, or whether caring for the sick supercedes saving our environment. All are worthy causes.

Instead, we looked at whether each agency achieves its mission. To do this, we identified a few key characteristics of successful nonprofits and then selected agencies that exemplify those characteristics. Most of the nonprofits on this list exhibit many or all of these six characteristics.

Second, this list clearly isn’t comprehensive or definitive. For example, we’ve excluded large nonprofits, which, almost by definition, are highly successful. They have more resources – financial, institutional and staffing – that make them more likely to succeed. Instead, we focused on small nonprofits that have a big impact compared to their size. To identify them, we’ve relied on the recommendations of their nonprofit peers – especially the funders, consultants and intermediate organizations that work with many agencies.

Finally, we don’t pretend that these are the only characteristics of successful nonprofits. If you ask the experts or search the literature, you’ll find a host of lists that purport to describe the “best practices” for nonprofit management. We considered many of those lists before settling on a few initial stipulations:

1. All great nonprofits have responsible and active boards of directors who exercise prudent oversight and governance.

2. The best agencies are always ethical and transparent in their operations.

3. Well-run nonprofits are managed in just as businesslike a fashion – in accounting, human resources and planning – as their for-profit counterparts.