5 Reasons to be Optimistic About Hawaii’s Clean Energy Future

Clean energy advocates say we’re on the right track to continue reducing emissions that lead to climate change. Here’s why, plus some of the challenges that we’ll have to overcome.

Part I: We Have a Lot to Be Optimistic About

It’s been 10 years since Hawaii set its first major energy independence goals through the Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative, a collaboration between the state and the U.S. Department of Energy, and four years since the state updated those goals with a mandate to generate 100 percent of its electricity sales with renewable sources by Dec. 31, 2045.

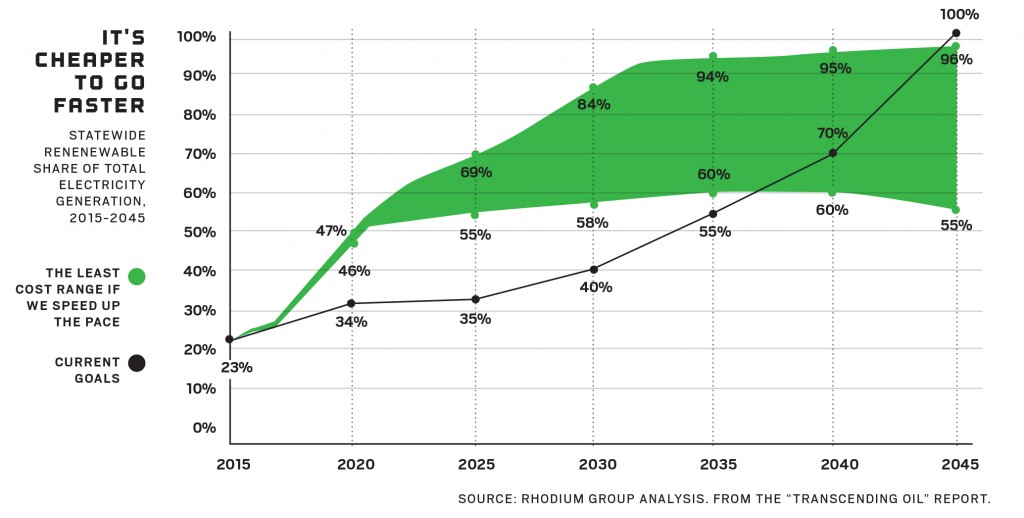

A report this year affirmed that Hawaii has what it takes to meet that goal. Called “Transcending Oil,” the report by research firm Rhodium Group and national organization Smart Growth America, said the state could even accelerate its transition to clean energy – and that acceleration would be cheaper than continuing at our current pace.

That’s because the costs of renewable energy are decreasing, making it possible for more and more companies and individuals to get involved in shaping our clean energy future.

“They’re basically saying you have everything you need to double renewable energy in half the time and reduce the greenhouse emissions, reduce the toxins, reduce dependency on oil and reduce the high (electricity) prices. That’s what this report is saying,” says Andy Karsner, who served as assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Energy for energy efficiency and renewable energy from 2005 to 2008.

“And so the question we’ve got to have is ‘Why not?’ ”

1: Hawaii Has the Ingredients for Clean Energy

Isolated by thousands of miles of ocean, Hawaii depends on oil more than any other state and, as a result, our electricity rates are more than double the national average.

We have a strong case to transition off fossil fuels, and Shelee Kimura, senior VP for business development and strategic planning for Hawaiian Electric Cos., says Hawaii can be optimistic that it’s making real progress toward clean energy. Hawaiian Electric and its affiliates provide power to Oahu, Maui, Molokai, Lanai and Hawaii Island.

Today, about 28 percent of Hawaii’s electricity is powered by renewable resources. Ten years ago, it was about 6 percent.

Most of that renewable energy is generated from solar power, says Carilyn Shon, administrator of the Hawaii State Energy Office. There are about 80,000 private rooftop solar systems across Hawaiian Electric’s service territories. On Kauai, there are about 4,000 private systems.

“(Honolulu is) now ranked first in the nation for per capita photovoltaic installations,” Shon says. “And that is due to a combination of activities and actions on the part of the state, with good policies, goals, good tax incentives from the state and the federal government, as well as regulatory action by the Public Utilities Commission.”

In addition to solar, there’s also power generated from wind, hydro, geothermal, batteries and biofuels. This mix is important, Kimura says, to make sure supply and demand are always balanced. Sources like wind and solar are intermittent and stop providing power when clouds cover solar panels or the wind stops blowing. “You don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket and just have one type of technology,” she says.

The shutdown of the Puna Geothermal Venture plant in May by the Kilauea eruption will reduce Hawaiian Electric’s renewable portfolio standard – the percentage of total utility sales consisting of renewable energy used by customers – from 27 percent in 2017 to 24 percent in 2018, says Shannon Tangonan, director of corporate communications for Hawaiian Electric. However, she adds that share is expected to reach 29 percent by 2019.

Several clean energy advocates say Hawaii is the perfect test bed to transition to energy independence. They say we have lots of renewable energy sources to generate electricity, and each island’s grid is small and independent of the others, meaning what works on one can be replicated elsewhere.

Brian Kealoha, executive director of Hawaii Energy, a ratepayer-funded energy conservation program, says the most exciting part of the clean energy transition is setting an example of how to eliminate fossil fuel emissions and “the ability for Hawaii to be that beacon of hope for the rest of the world.”

2: Renewable Energy is Getting Cheaper

The state’s current mandate calls for 40 percent of the state’s electricity sales to be generated by renewables by Dec. 31, 2030. According to the “Transcending Oil” report, it’s cheaper for Hawaii to accelerate its transition – to generate 58 to 84 percent of its energy with renewables by 2030.

“We’re leaving a lot of money on the table by not going faster, by going on our current schedule,” says Dawn Lippert, CEO of Elemental Excelerator, a local nonprofit accelerator that supports companies focused on water, energy, food and agriculture and mobility.

Elemental Excelerator commissioned independent research firm Rhodium Group and national organization Smart Growth Amwerica to analyze the state’s deployment of clean energy and write the “Transcending Oil” report.

The price of renewables has decreased over the last decade, the report says, because of innovation and economies of scale. In many applications, the cost for renewables is less than oil.

Such is the case on Kauai, where about 44 percent of its electricity needs in 2017 were met with power from biomass, hydro, batteries and solar power. In 2025, that share is expected to reach 80 percent, according to the Kauai Island Utility Cooperative.

David Bissell, president and CEO of the Kauai Island Utility Cooperative, says that providing solar to the grid without batteries cost the cooperative 20 cents per kilowatt hour in 2013. The solar power was purchased from rooftop solar customers who participated in the cooperative’s net energy metering program, which allowed the cooperative to purchase excess power from customers at a fixed rate. Recent grid-scale projects consisting of both solar and battery storage have come in at around 11 cents per kilowatt hour. The cost of oil is around 17 cents per kilowatt hour.

“It’s substantially lower than oil right now, which is why we wanted to keep going to renewables,” he says. What has helped keep these prices so low are the availability of state and federal tax credits. Without them, or even a decline in the amount of support they provide, the cooperative would not be able to employ as much renewable power.

Ernest Moniz, who served as the U.S. secretary of energy from 2013 to 2017, says the state has a tremendous economic driver to accelerate its transition to clean energy.

Hawaiian Electric anticipates it can reach 100 percent renewables by 2040 – five years ahead of the state’s mandate. Beth Tokioka, communications manager for the Kauai Island Utility Cooperative, says the cooperative has not set a specific date for when it will reach 100 percent but is certain it will meet the state’s 2045 goal.

Accelerating the state’s clean energy transition can also create an additional 3,500 jobs, the “Transcending Oil” report says. Michael Roberts, an economics professor at UH Manoa who helped review the report, says it’s reasonable to expect that Hawaii will have better employment opportunities because of its clean energy transition, though he’s hesitant to name a specific job number.

3: We’re Using Less Energy

Kealoha, the Hawaii Energy executive director, says energy efficiency added to new clean energy generation can get the state to its goal faster. The state also has a mandate for energy efficiency that stemmed from the Hawaii Clean Energy Initiative: to reduce the state’s energy consumption by 4,300 gigawatt hours by 2030.

Hawaii Energy was formed in 2009 to help Maui County, Oahu and Hawaii Island businesses and residents reduce their electricity consumption through rebates that encourage and reward energy savings. Since its inception, the program says it has saved 1,100 gigawatt hours – about 25 percent of the state’s goal. Kealoha adds that there are mechanisms in the marketplace, like codes and standards, that also help raise efficiency, including the state’s adoption of the 2015 version of the International Energy Conservation Code.

Kealoha says energy efficiency is an equalizer in the clean energy transition because everyone can participate, even if they don’t have a roof on which to install solar panels.

From July 1, 2017, to June 30, 2018, the organization says it helped local businesses save over $18 million on their electricity bills by switching out lightbulbs, practicing energy conservation and making changes to building exteriors, among other things. It also paid over $19 million in rebates to residents and businesses to reward investments in energy efficient equipment like appliances and lighting. One of the barriers to incorporating energy efficiency, especially in the residential sector, Kealoha says, is the upfront cost. Among businesses, the challenge is getting them to see energy efficiency as an investment in long-term savings, rather than a maintenance issue, he says.

At Maui Brewing Co., the goal has always been to leave a smaller footprint and maximize energy efficiency, says Garrett Marrero, president and CEO. Since its establishment in 2005, he says, the company has worked with Hawaii Energy to install low-flow water faucets, waterless urinals and more efficient lighting, among other projects. Now, the company is looking to become grid independent in 2019 through the use of solar, batteries and biodiesel generators. Despite the term “grid independent,” Maui Brewing will still be connected to Maui’s electric grid and can even assist the community in times of need by providing shelter and helping to store energy from Maui’s grid.

Eric Au of Marriott Resorts and Hotels says clients are attracted to energy efficient properties. He oversees engineering and facilities at 20 properties in Hawaii and French Polynesia. Energy efficiency in hotels can mean upgrading chiller plants, replacing boilers and heat pumps, switching out lights to LED and installing cogeneration units that produce and use electricity and heat. Worldwide, Marriott aims to reduce its electricity and gas usage by 30 percent by 2025.

Practicing energy efficiency allows people to get a feel for what their real energy needs are before deploying renewables, says Michael Unebasami, associate VP for administrative affairs for UH community colleges. He points to sources of wasted energy: “old equipment, inefficient HVAC systems, the lack of controls turning things on and off, demand charges – a lot of things that you can address before you decide how much renewables you need to make up the difference.”

That’s what UH Maui College and the four Oahu community colleges have been doing over the last several years. Today, they’re getting ready to incorporate renewables to transition the five campuses to be at or close to net zero in 2019. Net zero means the campuses will produce as much renewable energy as they consume. The entire UH system is mandated to reach net zero by 2035.

4: Innovation is Booming

Hawaii’s progress toward its goal is attracting innovative companies to help the state find solutions. Many have already come to the Islands to demonstrate their technologies, such as those funded by Elemental Excelerator.

One of the companies in its 2017 cohort was Kevala, a San Francisco-based data and analytics company. In July, it launched its Oahu Assessor Map, a tool that was developed in collaboration with about 80 local stakeholders and provides a street level view of the island’s electric grid, allowing people to evaluate different scenarios for how Oahu might integrate more clean energy. For instance, the tool can show what would happen to the grid if all roofs on the island were covered with solar panels.

“When you’re pioneering and you’re innovating you have to try things, you have to be willing to fail and then learn from that and then get back on and try it again.”

Shelee Kimura, Senior VP for business development and strategic planning, Hawaiian Electric Cos.

“We know what the end state will look like or the different ways that the future might sort of settle, but a lot will matter how we get there in the near term,” says Aram Shumavon, CEO and co-founder of Kevala. “Picking the right rate structures and the right policies to ensure a transition to higher penetration rooftop solar or to handle more wind – those are decisions that will need to be made in the next five to 10 years that will matter a lot for what the path to that end state really looks like.”

Another Excelerator-supported company, Shifted Energy, saw that the state’s renewable energy movement is excluding renters and low-income residents who cannot afford solar panels, batteries or electric vehicles.

The local company’s solution: using software and controllers to turn electric water heaters into batteries that can interact with the grid and help residents save money on their electricity bills. CEO Forest Frizzell says electric water heaters tend to be the primary or second-largest users of energy in a home, and 40 percent of Hawaii homes have them.

Shifted Energy tested its solution in 2015 when it partnered with Hawaiian Electric to install 499 grid-interactive water heaters at Kapolei Lofts, providing the utility with 2.5 megawatt hours of daily storage capacity and a tool to help stabilize the grid, whether it’s to integrate additional renewable energy or because a generator goes down.

The state’s renewable energy goal has allowed Hawaii to serve as a launching pad for Go Electric, an Indiana-based energy technology company that develops solutions for energy resiliency and microgrids. The Excelerator-supported company first came to Hawaii in 2013 to deploy a smart microgrid with a high penetration of renewables at Camp Smith, and today it’s building another on Hawai‘i Island, says Lisa Laughner, president and CEO.

Microgrids, she says, allow communities to be more resilient by separating themselves from the main electric grid. In the case of the Big Island lava flow, if lava were to cut off power from a central utility facility, a microgrid would prevent communities from being impacted by using local generating assets instead.

For Stem, a California-based technology company, Hawaii’s goal has helped to justify moving forward with its smart energy storage projects. Since participating in Elemental Excelerator’s program in 2013, the company has provided 1 megawatt of smart energy storage across 29 customer sites on Oahu. The idea was to treat the batteries as a single resource – like a power plant – to benefit both the grid and the customer.

Tad Glauthier, VP of Hawaii operations, says: “It would be easy to say ‘we have enough renewable energy on the system, let’s just stop there. It’s getting unstable, we have to stop.’ And we can’t say that.”

5: We’re Working on Clean Transportation

One of the greatest opportunities and challenges in transitioning to clean energy lies in mobility, Lippert says. Transportation – ground, marine and air – account for about two-thirds of Hawaii’s petroleum use.

The good news: Hawaii has the second most electric vehicles in the nation, per capita – after California – and the Islands’ mayors are committed to a shared goal of transitioning 100 percent of their ground transportation off of fossil fuels by 2045 and their fleet vehicles by 2035. In addition, Servco Pacific recently launched its Hui car-sharing service in urban Honolulu, opened the state’s first public hydrogen fueling station and began leasing its first fuel cell vehicle, the Toyota Mirai.

The problem, according to Jeff Mikulina, executive director of the Blue Planet Foundation, a nonprofit committed to getting the state to 100 percent clean energy, is that the state doesn’t have policies in place to make the shift to clean transportation happen. He says other places, like Britain, France, India and Norway, have mandates in place prohibiting the sale of gas-powered cars after a certain date.

Mark Fukunaga, chairman and CEO of Servco Pacific, says the challenge with electric vehicle adoption in Hawaii is that concerns about range, cost and charging time still exist. There are federal incentives in place, like a federal tax credit, and the state grants cars with electric vehicle license plates free parking at state and county lots and the use of high occupancy vehicle lanes, regardless of the number of people in the vehicle.

Makena Coffman, a professor in UH Manoa’s Department of Urban and Regional Planning, says these are good early adopter policies, but they can cause other problems once there are more electric vehicles. Other states have found that allowing hybrid vehicles in HOV lanes creates congestion. Michael Roberts of UH’s economics department says transitioning the transportation sector to clean energy will involve getting the right incentives and regulatory mechanisms in place.

In addition to electrifying transportation, other mobility solutions are already in place, like infrastructure for walking and biking, the bus system, the Biki bike-share program, the Hui car-sharing program and, in the future, rail. “There actually starts to be a network of ways to get around the city that’s really affordable and accessible for folks. So that’s one thing we see as a huge opportunity,” Lippert says.